Are bodybuilding and cross-training practices dangerous for promoting orofacial injuries? A scoping review

Abstract

Bodybuilding and cross-training exercises bring health benefits. However, orofacial injuries can occur during practice. This study aimed to map, analyze, interpret, and synthesize data from studies on the main orofacial injuries resulting from bodybuilding and cross-training practices. This scoping review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute and PRISMA-ScR methods, with high-sensitivity searches in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Embase, Virtual Health Library and the Google Scholar. Original scientific articles published up to May 2024 were included, which evaluated the presence of self-reported or professionally diagnosed orofacial injuries by bodybuilding and cross-training practitioners aged 18 years or older. Literature reviews, editorials, and guidelines were excluded. Tables and figures were used to map and summarize the results. Out of 30.485 potentially eligible articles, four were included. The main orofacial injuries identified in both bodybuilding and cross-training practitioners were dental damage (n = 4), temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders (n = 3), and traumas to oral soft tissues (n = 2) and facial soft tissues (n = 2). Dental damage and TMJ disorders were the most prevalent conditions among bodybuilding and cross-training practitioners. Therefore, dental damage and TMJ disorders were the most prevalent conditions among bodybuilding and cross-training practitioners. However, further prospective studies with more in-depth methodological designs and fewer biases are necessary.

1 INTRODUCTION

The health benefits of physical activity and exercise are clear; virtually everyone can benefit from becoming more physically active,1 as physical activities are powerful tools for preventing and treating chronic diseases.2 Physical activity is any bodily movement that results in energy expenditure, and its structured form, exercise, plays a significant role in public health.3

Bodybuilding is a highly popular form of physical exercise involving rigorous training and muscle development through weight lifting, cardio, and nutrition.4 Bodybuilding is a resistance exercise in which skeletal muscles are contracted voluntarily against a specific resistance. Specific resistance can be provided by body weight, external weights, or equipment to increase muscular strength, endurance, and local muscular power.5

Another physical exercise that has gained prominence is cross-training (CrossFit®). Cross-training incorporates rapid, successive, high-intensity ballistic movements to develop strength and endurance. Cross-training combines cardiovascular exercises, weight lifting and gym-type exercises to achieve this.6 Cross-training growth in the sports industry has been so significant that it and weightlifting have been ranked among the top 20 global fitness trends in 2022.7

Despite the growing success of cross-training and its beneficial effects, current literature questions its safety based on the considerable risk of injury due to the high intensity with which the exercises must be performed.8 The risk of injury also applies to bodybuilding exercises.9 Bone, muscle, ligament, and tendon injuries are possible injuries that bodybuilders may suffer.10 Furthermore, bodybuilders are also subject to orofacial injuries,11 especially those with increased overjet and Class II sagittal skeletal patterns, at all ages.12-15 The occurrence of orofacial lesions leads to the need for preventive measures by those who practice bodybuilding and cross-training.16 However, more needs to be investigated regarding the prevalence of orofacial injuries in bodybuilding and cross-training practitioners. Currently, no synthesis study encompasses the main orofacial injuries resulting from bodybuilding and cross-training. Such a study is of fundamental importance for healthcare professionals, especially in Dentistry, to be aware of the prevalence of orofacial injuries and establish preventive measures in bodybuilders and cross-trainers. Therefore, conducting a scoping review allows for synthesizing evidence and disseminating research results, identifying gaps and making recommendations for future primary research.17

Therefore, this scoping review aimed to map, analyze, interpret, and synthesize data from studies on the main orofacial injuries resulting from bodybuilding and cross-training practices.

2 METHODS

2.1 Protocol and registration

The review was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute method18 and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) protocol.19 The main consecutive execution steps of this study were: (1) identification of the research question and objective; (2) identification of relevant studies; (3) selection of studies according to predefined criteria; (4) mapping and analysis of data; and (5) grouping, synthesis, and presentation of data. The protocol for this review was registered on the Open Science Framework platform on September 18, 2023, with the registration DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/J6YVP.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Studies that met the following criterion were included: Original primary studies published up to May 2024 that identified self-reported or professionally diagnosed orofacial injuries in 18-year-old or older bodybuilders or cross-trainers.

2.3 Database

The electronic databases selected for this review were PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Embase, Virtual Health Library and the Google Scholar. Each database required a specific search algorithm, and no filters or data restrictions were selected in the searches.

2.4 Search

- Population—people over 18 years old.

- Concept—orofacial injuries.

- Context—bodybuilding and cross-training.

The detailed and high-sensitivity search strategy was developed for PubMed using combinations of various descriptors divided into three major groups: Adult, orofacial injuries, and bodybuilding and cross-training (Table 1). Adaptations of this search strategy were made for each database.

| Search terms | |

|---|---|

| #1 | “Young Adult”[Mesh] OR (Adult, Young) OR (Adults, Young) OR (Young Adults) OR “Adult”[Mesh] OR (Adults) OR “Athletes”[Mesh] OR (Athlete) OR (Professional Athletes) OR (Athlete, Professional) OR (Athletes, Professional) OR (Professional Athlete) OR (Elite Athletes) OR (Athlete, Elite) OR (Athletes, Elite) OR (Elite Athlete) OR (College Athletes) OR (Athlete, College) OR (Athletes, College) OR (College Athlete) OR “Face”[Mesh] OR (Faces) OR “Mouth”[Mesh] OR (Oral Cavity) OR (Cavity, Oral) OR “Tooth”[Mesh] OR (Teeth) |

| #2 | “Wounds and Injuries”[Mesh] OR (Injuries and Wounds) OR (Wounds and Injury) OR (Injury and Wounds) OR (Wounds, Injury) OR (Trauma) OR (Traumas) OR (Injuries, Wounds) OR (Injuries) OR (Injury) OR (Wounds) OR (Wound) OR “Lacerations”[Mesh] OR (Laceration) OR “Tooth Wear”[Mesh] OR (Tooth Wears) OR (Wear, Tooth) OR (Wears, Tooth) OR (Dental Wear) OR (Dental Wears) OR “Tooth Injuries”[Mesh] OR (Injuries, Teeth) OR (Injury, Teeth) OR (Teeth Injury) OR (Injuries, Tooth) OR (Injury, Tooth) OR (Tooth Injury) OR (Teeth Injuries) OR “Tooth Fractures”[Mesh] OR (Fracture, Tooth) OR (Fractures, Tooth) OR (Tooth Fracture) OR “Tooth Attrition”[Mesh] OR (Attrition, Tooth) OR (Dental Attrition) OR (Occlusal Wear) OR (Occlusal Wears) OR (Wear, Occlusal) OR (Wears, Occlusal) OR (Attrition, Dental) OR (Dental Attritions) OR “Tooth Erosion”[Mesh] OR (Erosion, Tooth) OR (Tooth Erosions) OR (Dental Erosion) OR (Dental Erosions) OR (Erosion, Dental) OR (Dental Enamel Erosion) OR (Dental Enamel Erosions) OR (Enamel Erosion, Dental) OR (Erosion, Dental Enamel) OR “Tooth Abrasion”[Mesh] OR (Abrasion, Tooth) OR (Abrasion, Dental) OR (Dental Abrasion) OR (Dental Abfraction) |

| #3 | “Resistance Training”[Mesh] OR (Training, Resistance) OR (Strength Training) OR (Training, Strength) OR “Circuit-Based Exercise”[Mesh] OR (Circuit Based Exercise) OR (Circuit-Based Exercises) OR (Exercise, Circuit-Based) OR (Exercises, Circuit-Based) OR (Circuit Training) OR (Training, Circuit) OR “High-Intensity Interval Training”[Mesh] OR (High Intensity Interval Training) OR (High-Intensity Interval Trainings) OR (Interval Training, High-Intensity) OR (Interval Trainings, High-Intensity) OR (Training, High-Intensity Interval) OR (Trainings, High-Intensity Interval) OR (High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise) OR (Exercise, High-Intensity Intermittent) OR (Exercises, High-Intensity Intermittent) OR (High-Intensity Intermittent Exercises) OR “Plyometric Exercise”[Mesh] OR (Bodybuilding) OR (Crosstraining) OR (Crossfit) |

2.5 Selection of evidence sources

Two reviewers independently conducted searches in the selected databases. After completing the searches, all references were exported to the online tool Rayyan® for duplicate removal. Subsequently, screening proceeded as follows: The reviewers independently analyzed the titles and abstracts of the selected studies. All reviewers collected and analyzed the full text of all abstracts that met the eligibility criteria. Any discrepancies between the reviewers, if not resolved through discussion, were resolved by intervention from a third reviewer.

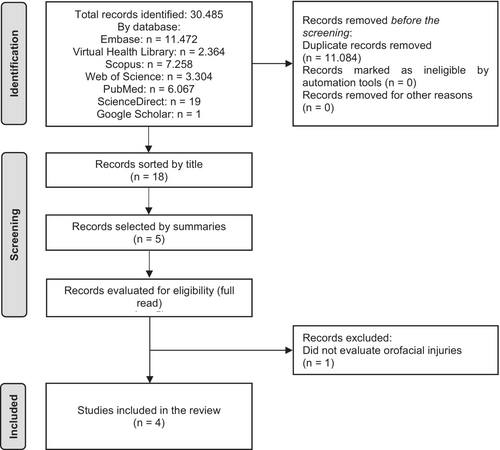

In addition, to complement the results, manual searches in the gray literature were also conducted for other studies that met the eligibility criteria. Manual searches were conducted by consulting the references of included studies and the main search results on Google Scholar. After selecting the studies, this entire selection process was summarized in a flowchart based on the PRISMA-ScR (Figure 1).

2.6 Data mapping process

A table was created by the reviewers to determine data extraction. The extracted data from each article were: study and country; study design; number and gender of participants; sample size calculation; blinding; randomization; examiner calibration; tested groups; type of exercise; orofacial injuries; method of identifying injuries; results; and authors' conclusions.

The authors of the included studies were contacted via the correspondence emails provided in the articles to obtain missing data. After 15 days, the absence of responses to the emails led to the data being considered “not reported” by the study21

3 RESULTS

3.1 Selected studies

The present scoping review conducted a comprehensive literature analysis encompassing 30.485 publications from seven databases. The screening process included four studies that aligned with the scope of this review (Figure 1).

3.2 Identification of studies

Of the four included studies, two were conducted in Brazil,22, 23 one in Switzerland,11 and one in Israel.10 All were quantitative cross-sectional studies, with publication years ranging from 2017 to 2023 (Table 2). Regarding the types of exercises investigated, three studies focused on bodybuilding,10, 11, 22 while only one article concentrated on cross-training.23

| Study and country | Study design | Participants | Sample calculation | Type of exercise | Practice time/ frequency | Way of identification of injuries | Reported orofacial injuries or regions affected by trauma | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mählmann & Filippi, 2023 Switzerland |

Cross-sectional quantitative |

239 men 363 women |

No | Bodybuilding | No time limitation | Online questionnaire |

Orofacial sphere: 202 (33,6%) TMJ: 121 (20%) Teeth: 72 (12%) |

A greater number of years of bodybuilding increased self-reported oral tissue trauma, with women more likely to report orofacial problems than men |

|

Bessa et al., 2021 Brazil |

Cross-sectional quantitative |

109 men 151 women |

Yes | Bodybuilding | Minimum of one year/ Minimum of one day | Physical questionnaire and intraoral clinical examination |

Attrition: 195 (80,9%) Abfraction: 38 (15,8%) Erosion: 7 (2,9%) Abrasion: 1 (0,4%) |

Abfraction was more frequent in those who practiced bodybuilding up to four times a week. Attrition and abfraction were the most unfamiliar dental injuries among practitioners, which could imply deficiencies in preventing these injuries |

|

Souza et al., 2021 Brazil |

Cross-sectional quantitative |

126 men 108 women |

Yes | CrossFit | No time limitation | Online questionnaire |

Head: 23 (21%) Mental protuberance: 22 (19,6%) Upper lip: 19 (16,9%) Upper teeth: 14 (12,5%) Tongue: 11 (9,8%) Nose: 10 (8,9%) Bottom lip: 4 (3,5%) Other facial region: 4 (3,5%) TMJ: 3 (2,6%) Lower teeth: 2 (1,7%) |

Preference should be given to the fabrication of mouthguards for the upper teeth, as they are more affected by trauma during CrossFit compared to the lower teeth |

|

Rubin et al., 2017 Israel |

Cross-sectional quantitative | 99 men | No | Bodybuilding | Minimum six years/four times a week | Physical questionnaire and extra and intraoral clinical examination |

Abfraction: 32 (32%) Indentations on the tongue: 28 (28%) TMJ disc displacement with reduction: 14 (14,2%) |

Resistance training alone may not be a risk factor for disc displacement. However, it can act as a potential risk factor for irreversible damage to hard dental tissues and contribute to postural and neck mobility deficiencies |

- Abbreviation: TMJ, Temporomandibular Joint.

The sample size of the studies ranged from 99 to 602 bodybuilders and cross-trainers, mostly women. Two studies determined the size by convenience,10, 11 and two reported calculating the sample size.22, 23 Only one study divided the sample into two distinct groups10: Group 1, which included those who dedicated themselves to extensive activities four times a week for more than 6 years, and Group 2, which comprised individuals who practiced as a hobby or for fun, training less than four times weekly.

Additionally, it is worth noting aspects related to calibration in the studies. The absence of this calibration was observed in two studies,11, 23 while the other reported intra-examiner10 and intra- and inter-examiner calibration.22

3.3 Methods and identified orofacial injuries

The orofacial injuries identified in the studies were reported or diagnosed through online questionnaires,11, 23 directly shared with the study participants. In the questionnaires, according to their perceptions, participants reported orofacial injuries they had experienced due to bodybuilding or cross-training. Alternatively, physical questionnaires were filled out by participants, followed by an orofacial clinical examination conducted by an examiner to identify or confirm the orofacial injuries reported by participants in the questionnaires.10, 22

The main orofacial injuries identified were dental damage,10, 11, 22, 23 with abfraction being the most common dental wear,10, 22 although two other studies reported dental injuries without specifying them.11, 23 Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders prevailed next,10, 11, 23 followed by traumas to soft oral tissues, mainly in the tongue,10, 23 and facial tissues in the extraoral region.11, 23 Only one study specified the type of TMJ disorder, which was disc displacement with reduction.10 Regarding traumas to soft tissues, the studies did not report the types of traumas (Table 2).

4 DISCUSSION

Physical exercise's benefits include improved physical performance, functional independence, cognitive abilities, and self-esteem.24 Bodybuilding, a training modality that uses a wide range of resistive loads,5 and cross-training, a high-intensity functional movement conditioning and strength program,25 are established examples of physical exercises. However, bodybuilders and cross-trainers are susceptible to injuries, wherein various factors influence the number and severity of these injuries.23

In bodybuilding, weightlifters are more prone to musculoskeletal injuries due to the repetitive nature and high intensity of their training, especially when performed without professional supervision.26 Concurrently, orofacial injuries are also prevalent in bodybuilders, involving primarily dental elements and the TMJ, as observed in the studies included in this review.10, 11, 22

In cross-training, the occurrence of injuries has also been common. One study observed that 38.6% of 184 practitioners had suffered some injury during cross-training, resulting in an injury rate of 3.4/1000 h, mainly in the upper joints.27 Concerning orofacial injuries, a study included in this review pointed out a prevalence of 89.2% of at least one orofacial trauma event during cross-training.23 Such orofacial injuries are common in cross-training, as they involve intense and explosive activities. Due to the nature of the exercises performed, the risk of impact and facial trauma can increase.28

When physical exercise practitioners perform inadequately or do not follow a training program devised by a professional, they are more susceptible to suffering some form of injury, underscoring the importance of seeking strategies to minimize the risk of injuries.29 Therefore, to reduce the risk of injury, professionals should prioritize the education and supervision of bodybuilders and cross-trainers, guiding them in proper techniques, especially when weightlifting is involved in the program.29

In addition to the type of physical exercise, the execution frequency can also influence the risk of orofacial injuries. One included study demonstrated that the longer the practice time of bodybuilding, the greater the risk of oral tissue traumas.11 Similarly, the practice time, training frequency, and the number of equipment used in the gym can directly interfere with the appearance of dental wear and bodily injuries.22 Such findings reinforce the relationship between the frequency and duration of bodybuilding practice with an increased risk of injuries.

In cross-training, the relationship between frequency and duration of practice also remains consistent. Regarding the CrossFit® modality, a study with 414 practitioners observed that the probability of injury for those practicing it for more than 12 months was 82.2%, a higher value than the corresponding probability for beginner athletes.29 Thus, the longer one practices cross-training, the higher the risks of injuries, including in the orofacial region. However, it proves to be a suitable training program for different age groups when conducted in a safe environment and under the supervision of qualified professionals.29 Therefore, the importance of implementing preventive strategies by professionals and practitioners to mitigate the risk of orofacial traumas is highlighted.

A cautious approach related to monitoring exercise execution is a good strategy. Through proper professional supervision, it is possible to ensure correct exercise execution, minimizing the risk of accidents and injuries, as guidance during training is correlated with a decrease in the injury rate.30

It was observed that dental damage was the most prevalent among bodybuilding and cross-training practitioners, mostly related to the loss of dental structure.10, 11, 22, 23 Dental damage was also evident in other forms of physical exercise, such as water polo, karate, handball, taekwondo,31 jiu-jitsu,32 boxing,32, 33 rugby, basketball, and field hockey.34 Dental traumas can occur after direct contact with a body or object or indirect contact with an object,35 which favors their frequent occurrences among practitioners.

Among dental damages, non-carious lesions were the most reported, in which abfraction corresponded to 50% of the included studies,10, 22 and attrition to 25%.22 Abfraction is characterized by the loss of tooth structure along the gingival margin and manifests itself with different clinical aspects.36 The causes of abfraction are mainly associated with tooth flexion in the cervical region caused by occlusal compressive forces and tensile stresses, which result in fractures in the hydroxyapatite crystals.36 Attrition, in turn, is characterized by the loss of opposing incisal and occlusal tooth regions caused by tooth-to-tooth contact.37

Non-carious lesions are considered one of the most prevalent dental problems, affecting around 60% of the population.38 Therefore, bodybuilders and cross-trainers must develop preventive measures to minimize the risks of the progression of non-carious lesions.

Furthermore, dental trauma, especially in upper anterior teeth, is more prevalent in people outside of normal occlusal patterns, such as those with increased overjet and Class II sagittal skeletal patterns, at all ages and stages of dental development.12-15 Furthermore, people in need of orthodontic treatments are more likely to suffer dental trauma compared to those without.13 Only one study showed that upper dental and lip injuries were more prevalent than lower injuries in cross-trainers.23 The studies included did not explore the association between the occlusal patterns of exercisers and the risk of dental trauma.

As for TMJ trauma, the included studies reported it as the most prevalent after dental damage,10, 11, 23 which was also related among handball players.39 Such traumas can be attributed to long-term micro-loading or short-term overload during exercise execution, resulting in tissue damage.35 Thus, contact sports present a particularly high risk of contributing to TMJ traumas.16, 40 The TMJ is vulnerable to injuries due to its anatomical configuration, as macro or microtraumas to the joint can result in dysfunction and debilitation.16

The macrotrauma includes fractures, dislocation and displacement. Microtrauma includes synovitis, internal derangement, capsulitis and tendonitis.16 Clinical symptoms of TMJ injury are pain, arthralgia, myalgia, TMJ sounds such as crepitus, popping, deviation of mouth, reduced mouth opening, otalgia, head and cervical pain, tinnitus, ear blockage, reduced functional and masticatory efficiency.16 It has been reported that the global prevalence of TMJ injuries was approximately 31% for adults and elderly, and 11% for children and adolescents,41 demonstrating that it is a problem of clinical relevance that deserves attention.

In general, orofacial traumas can result in various problems, such as deteriorating performance in physical exercise or sports.42 Additionally, they can affect activities of daily living due to potential alterations in facial expression, deterioration of pronunciation function, and decreased chewing capacity.43, 44 More severe cases can lead to functional, aesthetic, or psychological sequelae.43, 44

Given the risks of complications arising from orofacial traumas in bodybuilding and cross-training practitioners, it is suggested that practitioners take preventive measures through basic protective devices, such as helmets, facial masks, and, above all, properly fitted mouthguards. The mouthguard prevents strong contact between the upper and lower teeth during exercise execution, especially in practitioners who have the habit of clenching their teeth during practice, reducing the occurrence of dental traumas.23, 31, 45 The American Dental Association emphasizes the use of mouthguards due to the risk of orofacial injuries in at least 29 types of sports/exercises.46

Despite the results in this review reflecting the need for further discussions on the topic, the included studies have methodological limitations. They mainly relate to using questionnaires to identify orofacial injuries,10, 11, 22, 23 which rely on practitioners' subjective perceptions and are subject to recall bias. Additionally, the absence of clinical examinations in the orofacial region by an examiner in some studies11, 23 limits the identification of recent injuries related to exercises, as many practitioners lack specific knowledge for diagnosing orofacial injuries.

Therefore, further primary studies should be performed to solve these methodological limitations. Furthermore, as the included primary studies are cross-sectional, the prevalence of orofacial injuries in bodybuilders and cross-trainers reported may have been underestimated or overestimated. Also, there is a need to investigate better the factors that may contribute to the development of orofacial injuries, and the relationship between their occurrence and the occlusal and facial conditions of bodybuilders and crosstrainers. Thus, prospective cohort primary studies could conclude with less bias whether the practices themselves are risk factors for developing orofacial injuries and which occlusal and facial conditions are more prevalent in bodybuilders and cross-trainers.

Despite the particularities related to the execution of weight training and cross-training exercises, it is impossible to say whether there are significant differences concerning the risk of developing orofacial injuries when comparing the two practices, so further prospective primary studies are necessary to solve the doubt.

If the methodological gaps reported in this scoping review are filled in further primary studies, the previously mentioned limitations could be better understood. Then, professionals might plan better strategies to prevent orofacial injuries in bodybuilders and cross-trainers.

5 CONCLUSION

Dental damage and TMJ disorders were the most prevalent conditions among bodybuilders and cross-trainers. Knowing the prevalence of dental damage and TMJ disorders by health professionals is important to provide better guidance on the risks of injuries in bodybuilders and cross-trainers. Therefore, prevention methods, such as mouthguards, must be implemented to minimize orofacial trauma. However, more prospective studies are needed, with a more in-depth methodological design and less bias, which could stimulate additional discussions among health professionals, bodybuilders and cross-trainers.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mariana Silva de Bessa, Erik Vinícius Martins Jácome, and Caio Resdem Barroca Tanus contributed with Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, and Visualization. Boniek Castillo Dutra Borges, and Ana Clara Soares Paiva Torres contributed with Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, and Project Administration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), Brazil, for the financial support provided through the scholarships awarded to our Master’s students Mariana Silva de Bessa and Erik Vinícius Martins Jácome.

6 CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.