Developing a care pathway for hospital-based advance care planning for cancer patients: A modified Delphi study

Funding information: The project was funded by the German Cancer Aid (funding ID: 70113232).

Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study is to develop a care pathway for a hospital-based advance care planning service for cancer patients.

Methods

A web-based modified Delphi study consulted an expert panel consisting of a convenience sample of stakeholders including professionals with a special interest in advance care planning as well as a ‘public and patient involvement group’. After generating ideas for core elements of a care pathway in the first round, numerical ratings and rankings informed the multi-professional research steering group's decision process eventually resulting in a final pathway.

Results

The 41 participants in the Delphi study identified 177 potential core elements of the pathway in the first round. In two further rounds, consensus was reached on a final version of the pathway with 148 elements covering the 10 domains: prerequisites, organisation and coordination, identification and referral, provision of information, information sources, family involvement, advance care planning discussion, documentation, update and quality assurance.

Conclusion

We propose a care pathway for advance care planning for hospital patients with cancer based on the results of a Delphi study that reached consensus on an implementation strategy. Our study pioneers the standardisation of the process and provides input for further policy and research with the aim of aligning cancer patients' care with their preferences and values.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, advance care planning (ACP) has been championed as a pillar of high-quality, person-centred care (Institute of Medicine, 2015; National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2018) improving many patient- and carer-relevant endpoints (Brinkman-Stoppelenburg et al., 2014; Detering et al., 2010; Hjorth et al., 2021; Houben et al., 2014). It is a structured conversational process assisting ‘individuals to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, to discuss these goals and preferences with family and healthcare providers, and to record and review these preferences if appropriate’ (Rietjens et al., 2017). In Germany, ACP was first introduced by law with the Hospice and Palliative Act in 2015 and is now financed by statutory health insurance. However, the legislator currently restricts this service to residents of nursing homes and facilities for integration assistance. In the outpatient sector, for these populations sustainable concepts have already been proven and established (in der Schmitten et al., 2014, 2016). While this development shows substantial progress for medical care planning, it neglects the fact that other patient groups also harbour a considerable need to make provisions for health crises.

Cancer patients are prone to impaired decisional capacity at the end of life (Kolva et al., 2018), but the few ACP intervention trials for cancer patients have had rather inconclusive results (Canny et al., 2022; Green et al., 2015; Korfage et al., 2020; Pedrosa Carrasco et al., 2021). The multinational ACTION trial showed no impact of ACP on quality of life, symptoms, coping, patient satisfaction and shared decision-making (Korfage et al., 2020), stimulating the debate on traditional outcome measures, which not reflect the value of ACP experienced in clinical practice (Curtis, 2021).

In Germany, cancer patients are not only frequently cared for in hospital-based haemato-oncological outpatient clinics, there is also evidence that many patients require multiple hospitalisations during the course of their disease (Barnes et al., 2016). This circumstance can lead to the hospital team becoming the principal care provider. In these cases, the hospital staff takes the responsibility of managing high levels of distress and a wide range of palliative care needs of cancer patients and their caregivers (Wang et al., 2018). It stands to reason that hospital staff is, therefore, well suited to coordinate ACP initiatives with their patients. Furthermore, patients are often admitted to hospitals in situations of crisis and acute deterioration, which could be used as an opportunity to reconsider treatment goals.

Other countries are leading the way and have already recognised hospitals as an appropriate setting to initiate ACP conversations (Department of Health, 2014; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018). Despite national medical societies recommending that patients with incurable cancer should receive an offer of ACP (Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie, 2020), there is currently no established service for cancer patients in the German healthcare system, let alone in the hospital setting. First attempts at normalisation of hospital-based ACP services have been effective in increasing completion of advance directives (Jeong et al., 2021). Nevertheless, due to scarce evidence on implementation and limited empirical knowledge, the few pilot projects conducted are not subject to any normative standards for the ACP process.

To address the apparent lack of knowledge about the implementation of the ACP process in hospitals, we sought to identify and structure meaningful action steps. We, therefore, designed a modified Delphi study to develop a comprehensive care pathway for hospital-based ACP for cancer patients aiming to achieve high-quality standardisation of the process to ultimately provide guidance to facilitators, service providers and policymakers.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

Based on a non-systematic literature review of key publications on implementation of ACP (Jimenez et al., 2018; Lovell & Yates, 2014; Lund et al., 2015; Rietjens et al., 2017), relevant themes were identified and used to create open-ended questions for the first round of a modified online Delphi study. We consulted an expert panel over the course of three rounds between April and August 2021 using the online survey tool Unipark. The first round served to generate ideas for potential elements of a care pathway. To decide on inclusion or exclusion, elements were consecutively presented as written statements for numerical ratings (Round 2) and rankings (Round 3). Relevant results of the previous round were presented to the panel as a basis for decision-making. The panel was offered the opportunity to provide free-text comments to supplement and contextualise their ratings or elaborate their opinion, ultimately informing the research steering group's decision process. At the end of each round, panel members were asked to enter their email addresses if they were willing to participate in subsequent rounds of the study. The survey link was accessible for 3 weeks for the first round and 2 weeks for the following rounds.

Before the individual rounds were activated, the survey was checked for comprehensibility and user-friendliness by lay people and researchers who neither belonged to the core research team nor had in-depth knowledge on the topic of ACP.

Our research was conducted and is reported according to standards for Delphi studies proposed by Jünger et al. (2017).

2.2 Sampling and recruitment

The panel consisted of a convenience sample of German-speaking stakeholders including professionals with academic or practical expertise in ACP and a ‘public and patient involvement group’. Fifty-four experts with freely available contact details who spoke at the first German ACP congress (DiV-BVP, 2020) in Cologne in 2020 were contacted. We further reached out to 15 facilitators, trainers and academics in the field of ACP known to the research team and 69 cancer patients who previously participated in ACP research. Forty-four lead contacts for support groups for cancer patients were asked to forward the invitation to their members. Potential panel members were invited to participate by responding directly to a link provided in an email invitation. Additionally, we invited patients and carers through social media, more precisely via the public Instagram profile Let's talk about Krebs [@letstalkaboutkrebs] (2021) and open-access German Facebook groups for cancer patients and/or caregivers.

2.3 Data collection

In the first Delphi round, participants wrote free-text comments responding to explicit questions covering a range of aspects concerning the implementation of ACP for cancer patients in the hospital setting. In the following round, participants were asked to provide a rating on each element's usefulness according to a nine-level Likert rating scale (1 = not useful, 9 = very useful). If the results from Round 2 revealed conflicting alternatives or ambivalent answers, these were presented for ranking in the third round. Decision criteria for ratings and rankings, that is, adoption or rejection of an item, depended on participants' own definition. Based on the fact that not every member of our heterogeneous panel was familiar with all hospital processes, the answer option ‘beyond my expertise’ was also selectable.

Anonymity of the participants was maintained throughout all rounds, contact information could not be linked to the answers.

2.4 Analysis

For each round, we summarised demographic characteristics and personal information of panellists using counts (percentages) and means (standard deviations) as appropriate. A.P. and B.P. performed an inductive content analysis of responses extracted from Round 1 using MAXQDA 2020. In a first step, the two authors independently clustered responses of 20 data sets representing relevant ideas to codes through line-by-line review. Ensuring a structured approach, each code received a ‘code definition’. The response passages assigned to the codes were compared both within individual responses and across participants, and overarching themes were identified and combined into a code structure which was expanded in an iterative process to all data as new aspects arose. Based on these results, individual elements of the care pathway could then be converted into statements. To enhance rigour and confirmability, team meetings served to review and redefine statements before presenting them to the panel in the following rounds.

Ratings derived in the second round were analysed according to the method used by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Health Care Quality Indicators project (Mattke et al., 2006). Owing to skewed data, we used the median as a measure of central tendency with ratings of 7 to 9 indicating support for an item, 4 to 6 ambiguity and 1 to 3 rejection.

2.5 Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the Philipps-University Marburg (ID-No.: 200/20). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the EU data collection directive.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

We conducted a three-round Delphi study involving a 41-member expert panel including 12 cancer patients, four carers and 25 professionals. Of these initial respondents, 70.7% completed Round 2 and 51.2% Round 3. In Rounds 2 and 3, consensus was reached with professionals who had an average of 14.4 (SD ± 12.6) to 14.6 (SD ± 5.4) years of experience in hospital work; 88.2% to 92.3% of them actively engaged in ACP discussions in the month prior to the survey with a mean of 3.7 (SD ± 6.2) to 4.8 (SD ± 5.4) discussions per month. Further participant characteristics for each round are provided in Table 1.

| Round 1 (n = 41) | Round 2 (n = 29) | Round 3 (n = 21) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| Expert status | |||

| Cancer patient | 12 (29.3%) | 9 (31.0%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| Carer | 4 (9.8%) | 2 (6.9%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Professional | 25 (61.0%) | 18 (62.1%) | 14 (66.7%) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 22 (53.7%) | 12 (41.4%) | 7 (33.3%) |

| Male | 19 (46.3%) | 16 (55.2%) | 13 (61.9%) |

| Not given | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 50.2 (13.7) | 51.4 (15.1) | 54.6 (13.8) |

| Family status | |||

| Single | 9 (22.0%) | 3 (10.3%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| Non-civil relationship | 4 (9.8%) | 7 (24.1%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| Married | 25 (61.0%) | 16 (55.2%) | 13 (61.9%) |

| Divorced | 3 (7.3%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Widowed | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Not given | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Patients | |||

| Cancer site | |||

| Prostate | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (50.0%) |

| Breast | 2 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Haematological | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Skin | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Multiple | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Unknown primary | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Educational level | |||

| No professional training | 2 (16.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Non-university professional education | 3 (25.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| University education | 7 (58.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (66.7%) |

| Carers | |||

| Carers' relationship to patient | |||

| Spouse | 2 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Parent | 1 (25.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Friend | 1 (25.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (100.0%) |

| Educational level | |||

| No professional training | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-university professional education | 2 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| University education | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (100%) |

| Professionals | |||

| Professional background | |||

| Nurse | 3 (12.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Physician | 12 (48.0%) | 8 (44.4%) | 6 (42.9%) |

| Psychologist | 1 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Theologist | 1 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ethicist | 2 (8.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (14.3%) |

| Researcher | 3 (12.0%) | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (14.3%) |

| Other | 3 (12.0%) | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| Professional focus | |||

| Outpatient care | 7 (28.0%) | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| Inpatient care | 8 (32.0%) | 5 (27.8%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| Research | 5 (20.0%) | 5 (27.8%) | 4 (28.6%) |

| Education | 2 (8.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Other | 3 (12.0%) | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (21.4%) |

- Note: Number of participants (n), standard deviation (SD) and percentage (%).

3.2 Consensus building

The qualitative analysis of Round 1 identified 10 essential domains for hospital-based ACP for cancer patients: prerequisites, organisation and coordination, identification and referral, provision of information, information sources, family involvement, ACP discussion, documentation, update and quality assurance. These domains were covered by 177 key statements representing potential elements of a care pathway. In the second round, 153 of these elements (86.4%) received support according to median ratings. After assessment of these elements by the research steering group, 10 were merged under two existing more generally phrased statements that also reflected them in content. Seven elements were presented again in Round 3 to clarify priorities between competing or opposing concepts. In the context of other supported statements, one element was considered to be out of the hospital's sphere of influence and was thus not integrated into the pathway. Ten elements (5.6%) were rated below the cut-off of 4 resulting in exclusion. Median ratings reflected ambiguity for 14 elements (7.9%). Four were excluded due to a competing element scoring a median greater than or equal to 7. Two elements could be directly integrated into the care pathway as they represented a natural consequence of other supported elements. Lastly, six were put to the vote again in Round 3 to receive a final decision on inclusion or exclusion. In order to better explore relationships between individual elements presented in Round 2, some new statements were drafted and presented for voting in Round 3. In this following round, 21 elements were ranked by the panel using nine categorical questions, of which the highest ranked could ultimately be included in the care pathway. The final care pathway, therefore, encompasses 148 elements.

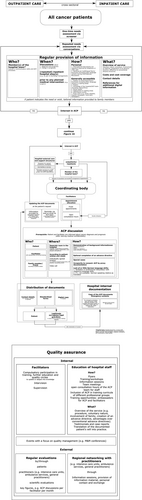

In principle, the voluntary nature of participation was identified as a basic but necessary prerequisite. To ensure voluntary use of services, panellists offered several strategies that were incorporated into the care pathway. Furthermore, panellists considered it obligatory to secure funding without financial contribution by the patients or families. The final care pathway is shown in Figure 1a–c. For a full list of the included elements please see the Supporting Information.

4 DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, we have developed the first comprehensive care pathway for ACP for hospital patients with cancer, by means of a three-round modified Delphi study. The individual elements identified demonstrate how ACP may be integrated across sectors in outpatient and inpatient hospital care using a step-by-step approach. It covers a variety of domains, starting with prerequisites such as voluntariness, through organisation and coordination, identification and referral, provision of information, information sources, family involvement, ACP discussion, documentation, update and up to quality assurance.

With regard to hospital management, our study advocates for a coordination body as the centrepiece for the service, directly accessible to the hospital team and patients. On the one hand, in that way, the care pathway offers patients the possibility to arrange ACP discussions on their own, so that independent and, above all, unconstrained, voluntary decisions can be made. The autonomy of the patients is strengthened by allowing them to register for the service at any time according to their needs. However, in order to arrive at informed decisions, distinct information sources, as well as crucial information content about ACP, were recommended by the study participants. On the other hand, the implementation of a coordination body also enables the hospital team to initiate the ACP process on the patient's request if overburdened by administrative matters. In addition, this support service relieves the clinical team of organisational tasks without excluding them from the decision-making process.

In order to further improve patient care, the need for meaningful and economic strategies to select and prioritise patients for ACP discussions have been proposed in the past (Cerulus et al., 2021; Mohan et al., 2021). Our results suggest that ACP should be offered to all cancer patients under hospital care, bar none. Given the low level of awareness of ACP and advance directives (Evans et al., 2012; Hubert et al., 2013; Justinger et al., 2019), additional needs assessment for ACP is considered sensible and best achieved through a combination of structured screening processes and conversational techniques in face-to-face communication. Unfortunately, our findings remain vague on how to address the challenges of finding the most appropriate time to screen patients for ACP needs (Billings & Bernacki, 2014) and adequate screening methods.

Our study did conclude with some useful suggestions to improve the patient experience during ACP conversations, for example, through the use of information aids and spatial conditions. This also comprised some measures for vulnerable patient groups such as the provision of translators for non-German-speaking patients or proxy documentation for incapacitated patients. Yet our study could have revealed more detailed information about how to structure the ACP discussions. While efforts have been made to optimise ACP procedures for patients and caregivers (Butler et al., 2014; in der Schmitten et al., 2016; Pedrosa Carrasco et al., 2021; Sellars et al., 2019), so far, there are no robust recommendations on standardisation actions in the hospital setting demanding more research in this area.

Apart from clinical implementation of ACP into routine care, our care pathway additionally comprises the understudied issues of documentation, update and quality assurance. The pathway ensures that patients' end-of-life decisions are effortlessly transmitted to practitioners but can also be updated easily. Access to convenient documentation and updating of ACP is of utmost importance in that they reflect and guarantee the current validity of the patient's will.

As a result of previous research on ACP in the hospital setting, it was suggested that a quality assurance framework be established to continuously monitor the quality of ACP discussions (Allers et al., 2019). Quality initiatives identified in our study included recommended service evaluation by various stakeholders but also raising awareness of ACP within hospital teams and qualification of facilitators (Gilissen et al., 2018). The meaningfulness is consistent with the results of a systematic review in which training programmes for health professionals in ACP showed positive effects on knowledge, attitude and skills (Chan et al., 2019). These aspects of quality assurance integrated in our care pathway are, therefore, expected to maintain an effective, scientifically sound and patient-centred ACP service in the long term.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

Despite sceptics of the Delphi technique arguing that its reliability and validity have not been confirmed (Hasson & Keeney, 2011; Keeney et al., 2001), the study design has been proven successful in earlier consensus research on ACP (Mohan et al., 2021; Sinclair et al., 2016; Sudore et al., 2017; Sudore et al., 2018). The choice of a modified Delphi method resulted from decisive advantages for the development of a care pathway. First, ACP for cancer patients, particularly in the hospital setting, is not routine in Germany, meaning that the direct experience of the experts in this area can certainly be considered limited. A key strength of our study lies in the structured consensus process involving professionals with clinical experience in hospitals and practical experience with ACP, so that a realistic assessment of the feasibility of the individual pathway elements can be assumed.

Second, for the purpose of our study, the traditional Delphi approach underwent some modifications. Instead of supplying participants with traditional hard copies of the survey, it was opted for a web-based survey to receive consensus on a care pathway. This methodology did not only accelerate and facilitate data collection and analysis but also increased dissemination covering a geographically spread sample. Most importantly, however, it ensured participant safety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Third, a high level of agreement for the individual elements indicates that our pathway may be suitable for different hospital settings and patient groups.

However, our modified Delphi study also faces some noteworthy limitations. First, response rates for online questionnaires are known to be notoriously low (Dobrow et al., 2008; Koo & Skinner, 2005; Petrovčič et al., 2016) which may explain limited participation and high attrition in our sample.

Second, the representativeness of the sample could be impaired by the chosen design possibly entailing accessibility issues, for example, due to lack of internet access, poor internet skills, visual impairment, illiteracy or low educational level of representatives of patients and public.

Third, by incorporating nonprofessional people's perspectives into the development process, patients' views in particular, greater meaningfulness of the pathway could be achieved. Nevertheless, despite contacting different ‘patient and public involvement groups’, the ratio of patients and carers over professionals is lower as hoped, with a dominating proportion of physicians. While experienced professionals may have a good insight into patients' needs and clinical processes, there is a small risk of a normative perspective in the evaluation of the presented pathway elements. It is therefore essential to verify how the care pathway performs in clinical practice.

Lastly, our pathway was designed for the German healthcare system, so that general applicability is not necessarily given. Thus, further studies would be important to show how an implementation could be accomplished in other countries.

5 CONCLUSION

ACP is an emerging field in Germany for which accessibility and quality of care should be ensured through a dedicated and well-designed care pathway. Our study represents an important first step in standardising the ACP process by means of a care pathway that may provide guidance for the implementation of high-quality ACP in clinical programmes and facilitates the comparison of results of future research. Using a rigorous methodology, we found that merging the perspectives of professionals, cancer patients and caregivers resulted in a patient-centred care pathway suitable for the hospital setting. The challenge ahead is to evaluate in a follow-up study whether the proposed care pathway is feasible, acceptable and effective. In addition, the knowledge gap on screening methods and the most appropriate time to screen patients for ACP needs remains to be filled.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our sincere thanks go to the expert panel for their contribution to developing the pathway. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available upon request.