Impact of the third national ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ Breast Cancer in Women over 70 Campaign on general practitioner attendance and referral, diagnosis rates and prevalence awareness

Funding information: Public Health England

Abstract

Objective

More than a third of women diagnosed with breast cancer in England, and over half of those who die from it, are over 70. The Be Clear on Cancer Breast Cancer in Women over 70 Campaign, running three times, 2014–2018, aimed to promote early diagnosis of breast cancer in England by raising symptom awareness and encouraging women to see their general practitioner (GP) without delay. We sought to establish whether the third campaign had successfully met its aims.

Methods

Metrics covering the patient pathway, including symptom awareness, attending a GP practice with symptoms, urgent GP referral, diagnosis and stage of cancer, were assessed using national cancer databases and two household surveys.

Results

The third campaign was associated with an increase in urgent cancer referrals, and therefore mammograms and ultrasounds performed. This was associated with an increase in breast cancers diagnosed. There was a delayed effect on GP attendances. Awareness of breast cancer prevalence for the 70-and-over age group improved. Impact on these metrics diminished across successive campaigns.

Conclusions

Future campaigns should focus on harder-to-reach women and include GPs as targets as this campaign showed a potential to affect referral behaviour.

1 INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer in women in England, with around 185,000 women diagnosed between 2014 and 2018 (National Audit of Breast Cancer in Older Patients, 2020). Of these, over a third were aged 70 years or over (National Audit of Breast Cancer in Older Patients, 2020; Public Health England, 2020c) and over half the 9500 women in England who died from BC (Office for National Statistics, 2019b). Survival is lower in older women even when adjusted for increased overall mortality. The decrease in survival with stage is also greatest in older women (Office for National Statistics, 2019a). Lower survival rates in older women may be explained by advanced stage on average in older groups, possibly due to poorer knowledge of non-lump BC symptoms or delay visiting their general practitioner (GP) upon discovering symptoms (Linsell et al., 2008). Furthermore, physicians may overlook or misinterpret symptoms (Hafström et al., 2011). Additionally, women diagnosed symptomatically rather than through screening are more likely to have breast cancer subtypes with poorer outcomes, while women diagnosed through screening are more likely to have luminal A disease, which has a better prognosis (Crispo et al., 2013). Moreover, older women are less likely to receive treatment for BC, which affects outcomes (Gaitanidis et al., 2018). Delay in the presentation of BC of 3 months or more can result in diagnosis with later-stage disease and reduced chances of survival (Williams, 2015). Routes to BC diagnosis are influenced by age, as only women aged 50–70 years are routinely invited for population-based screening and women outside of that age range must request a breast-screening appointment (National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service, 2021). Cancer awareness is still important in the over-70 age group as absolute risk of breast cancer increases with age.

Better knowledge of symptoms can reduce delays in help-seeking for cancer symptoms; therefore, behaviour change campaigns may increase knowledge of BC symptoms in women over 70 and to encourage them to present to their GP with symptoms (Petrova et al., 2020). Mass media campaigns can produce positive changes in health-related behaviours and are a useful component of comprehensive approaches to improving population health behaviours (Wakefield et al., 2010).

The ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ (BCoC) programme is an overarching campaign with specific campaigns for different cancers. BCoC aims to promote the early diagnosis of cancer in England by raising public awareness of its signs and symptoms, and to encourage people to see their GP without delay (Public Health England, 2020a). BCoC is led by Public Health England (PHE), in partnership with the Department of Health and Social Care, and National Health Service (NHS) England. The BCoC Breast Cancer in Women over 70 (BCW70) campaign was first piloted in 2012, running nationally in 2014, 2015 and 2018. Objectives included increasing BC knowledge in women over 70 that they were still at risk, that a lump is not the only sign, that early detection makes BC more treatable and they visit their GP if they noticed signs or symptoms. The campaigns were promoted through multiple channels, including television, press and screens in GP waiting rooms, online advertising, direct mailing of letters and leaflets and a campaign website.

Evaluation of these successive campaigns demonstrated objective increases in awareness of the campaign messages, and an increase in patients diagnosed immediately following the campaign (National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service, 2014). The BCoC campaigns influenced help-seeking by patients and referral patterns by GPs, with some impact on diagnosis (both incidence and stage), although no clear evidence on survival (Lai et al., 2020). The third campaign differed from the first two in that it was run on a reduced budget, which resulted in reaching fewer women than the earlier campaigns.

This paper reports an evaluation of the third BCoC BCW70 campaign. We assess the extent to which the third campaign influenced the target demographic, whether it met the aims and objectives, and compares the third national campaign to the two earlier campaigns. Clinical metrics and the impact on public awareness and attitudes towards help-seeking for BC symptoms are examined.

2 METHODS

2.1 Campaign overview

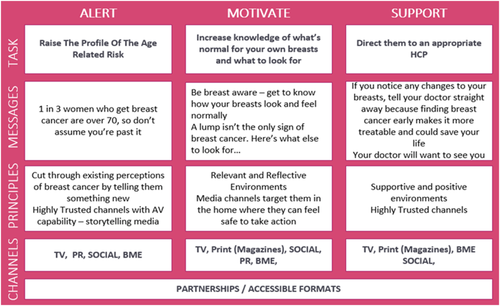

The third national BCW70 campaign ran from 22 February 2018 to 31 March 2018 in England. A communication framework, based on a modified version of the Government Communications Standards, was designed by PHE Marketing and Wavemaker, an external media planning agency (Wavemaker, 2018). The framework consisted of three stages: Alert, Motivate and Support (see Figure 1). Further details on the campaign can be found on the BCoC website (Public Health England, 2020b).

2.2 Data sources and metrics

All data used in this study were anonymous and acquired from external sources. No primary data collection or participant recruitment was undertaken by the study team. Participants in the symptom awareness survey were sampled from a cohort of a market and social research agency (Kantar Ltd), and all had given prior consent to be approached for such surveys and to have their responses shared with third parties. All remaining data were acquired from publicly owned, anonymised datasets. As such, ethical approval for this study was not sought.

The main data sources used for the metrics were The Health Improvement Network (THIN), National Cancer Waiting Times Monitoring Data Set and Diagnostic Imaging Dataset. Data were collected for a series of metrics covering the patient pathway from symptom awareness, attending a GP practice with relevant symptoms, urgent GP referral through to diagnosis of cancer and stage at diagnosis. The analysis for each metric compared the period during/shortly after the campaign (analysis period) to the same period in the previous year (comparison period). The analysis and comparison periods are slightly different for each metric due to when we might expect an impact of the campaign to occur (National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service, n.d.). For example, a cancer diagnosis would not be expected until at least 2 weeks after the first presentation at the GP (see Table 1).

| Metric | Definitions | Data source | Temporal grouping | Analysis/comparison period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP attendances for breast symptoms |

Breast symptoms were defined as a breast lump; changes in the size or shape of the breast, the skin of breast or the nipple; nipple discharge; and pain in breast or armpit. READ codes can be found in Table A1. Information on the number of GP practices submitting data each week (which decreased from 192 to 115 practices over the period considered) was also extracted. |

The Health Improvement Network (THIN) | Data were grouped into weeks and adjusted to account for bank holidays. |

A: 26 Feb to 15 April 2018 C: 27 Feb to 16 April 2017 Aa: 16 April to 24 June 2018 Ca: 17 April to 25 June 2017 |

| Urgent referrals for cancer and breast symptoms | People urgently referred by the GP with suspected cancer or breast symptoms. | National Cancer Waiting Times Monitoring Data Set | Data were grouped according to the month the patient was first seen in secondary care. |

A: March to April 2018 C: March to April 2017 |

| Cancers diagnosed from an urgent referral for cancer or breast symptoms |

Breast cancer was defined as ICD-10 C50 and D05. Includes patients diagnosed with breast cancer from an urgent referral for suspected breast cancer or breast symptoms. |

|||

| Cancer diagnoses in the Cancer Waiting Times database |

Breast cancer was defined as ICD-10 C50 and D05. Includes patients diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer by the NHS in England. |

National Cancer Waiting Times Monitoring Data Set | Data were grouped according to the month the patient was first treated. |

A: April to May 2018 C: April to May 2017 |

| Cancers diagnosed in the National Cancer Registration Dataset | Breast cancer was defined as ICD-10 C50 and D05. | National Cancer Registration Dataset | Data were grouped into weeks and adjusted to account for bank holidays. |

A: 5 March to 3 June 2018 C: 6 March to 4 June 2017 |

| Early-stage at diagnosis |

Breast cancer was defined as ICD-10 C50. Numerator: Early-stage was defined as (TNM) stage I/II. Denominator: Breast cancers with known and valid stage. |

|||

| Diagnostics in secondary care |

Ultrasounds of the breast and mammograms. NICIP and SNOMED codes can be found in Table A2. The data contain details of referrals for imaging by GPs, consultants and other healthcare professionals. |

Diagnostic Imaging Dataset | Data were grouped into months. |

A: March to May 2018 C: March to May 2017 |

- Note: A—analysis period; C—comparison period.

- a Post-campaign analysis period: to ascertain whether the campaign continued to have an impact on individuals visiting general practitioner (GP) with symptoms an additional analysis period (beyond 2 weeks after the campaign ended) was defined a priori.

2.2.1 Symptom awareness/attitudes to help-seeking

To evaluate the impact of the campaign on symptom awareness and attitudes to help-seeking, face-to-face interviews at home were undertaken by a social research agency (Kantar, 2020). Participants were randomly recruited with set quotas for specific demographics (age, geographic location, sociodemographic status and employment status) to ensure that respondents were representative of the target population (women aged 70 and over). Different participants were used for the pre- and post-campaign surveys, ensuring similar demographic profiles for each by quota sampling matched by weighting to match population statistics (see Table 2). Verbal consent was obtained at the start of the interview. Questionnaires were developed in previous BCoC campaigns (Lai et al., 2020) and adapted for the third BCW70 campaign to be appropriate for the campaign objectives, which changed slightly for each campaign.

| Age | Ethnic origin | Marital status | Social grade | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 70–79 | 80+ | White | Mixed | Asian/Asian British | Black/Black British | Chinese/Other | Non-white | Married/living as married | Single | Widowed/divorced/separated | ABC1 | C2DE | |

| Pre-campaign | 278 | 176 (63.3%) | 102 (36.7%) | 264 (95.0%) | 3 (1.1%) | 5 (1.8%) | 5 (1.8%) | — | 13 (4.7%) | 88 (31.7%) | 22 (7.9%) | 167 (60.1%) | 137 (49.3%) | 141 (50.7%) |

| Post-campaign | 357 | 225 (63.0%) | 132 (37.0%) | 340 (95.2%) | 3 (0.8%) | — | 8 (2.2%) | 6 (1.7%) | 17 (4.8%) | 116 (32.5%) | 31 (8.7%) | 210 (58.8%) | 177 (49.6%) | 180 (50.4%) |

Pre-campaign data collection occurred between 2 and 20 February 2018, and post-campaign data collection occurred between 6 April and 1 May 2018.

2.2.2 Clinical metrics

Table 1 provides details on data sources, temporal groupings of the data and inclusion criteria for each clinical metric.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Analyses included women aged 70 years and over. The outcome metrics including weekly or monthly counts (except early-stage at diagnosis) were analysed using Poisson regression or negative binomial regression with one binary variable for the comparison and analysis period. Results are presented as total counts in each period, the estimated rate ratio (analysis period compared to the comparison period) with 95% confidence intervals and associated p-values. For GP attendances, the number of GP practices contributing data into THIN (The Health Improvement Network, 2021) each week was added as an offset to the model; therefore, the results are presented as count per practice. For symptom awareness/attitude to help-seeking and early-stage at diagnosis, counts were aggregated, and proportions calculated for the comparison and analysis periods. The percentage change between the two periods was calculated, and p values estimated using a two-sample test of proportions. Trends in counts and proportions over time were analysed using visual displays, with data covering 2017 to 2018. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was conducted in Stata 16 (StataCorp, 2019).

3 RESULTS

The following results are for women aged 70 years and over and refer to the rate in the analysis period compared to the comparison period as defined above, unless stated otherwise (Table 1).

3.1 Symptom awareness/attitude to help-seeking

There was a significant 6.0% (95% CI: 1.1% to 10.9%) increase in the proportion of respondents who identified that one in three BCs are diagnosed in women over 70 each year (p value = 0.019). There was a significant 9.3% (95% CI: −16.8% to −1.8%) decrease in the proportion of respondents who identified ‘pain in the breast’ as a warning sign of breast cancer (p value = 0.017).

There was no post-campaign increase in the proportion of respondents correctly identifying that a ‘lump or thickening in the breast or armpit’, ‘change(s) to the nipple(s)’, ‘change(s) to the skin of the breast(s)’, ‘change in the shape or size or feel of the breasts’ or ‘nipple discharge’ could be a symptom of BC (all p > 0.05). However, awareness of these symptoms was high pre-campaign, ranging from 65.5% for ‘change(s) to the skin of the breast(s)’ to 84.5% for ‘lump or thickening in the breast or armpit’.

Before the campaign, most patients believed that they would be too embarrassed to talk to their GP about BC symptoms (87.4%), were worried about wasting the doctor's time (85.3%) or scared to know that they have BC (48.6%). These proportions were not significantly different after the campaign. The proportion of women who did not believe that their ‘GP/doctor would be difficult to talk to about the signs and symptoms of breast cancer’ increased significantly by 8.3% (95% CI 1.5% to 15.1%) from 21.9% before the campaign to 30.3% after the campaign (p = 0.019; see Table 3).

| Metric | Comparison period (pre 3rd campaign) N = 278 | Analysis period (post 3rd campaign) N = 357 | Difference in percentage (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement of symptoms being a warning sign of breast cancera, n (%) | ||||

| A lump or thickening in the breast or armpit | 235 (84.5) | 298 (83.5) | −1.1% (−6.8% to 4.7%) | 0.718 |

| Changes(s) to the nipple(s) | 206 (74.1) | 269 (75.4) | 1.2% (−5.6% to 8.1%) | 0.719 |

| Change(s) to the skin of the breast(s) | 182 (65.5) | 242 (67.8) | 2.3% (−5.1% to 9.7%) | 0.538 |

| Change in the shape or size or feel of the breasts | 207 (74.5) | 278 (77.9) | 3.4% (−3.3% to 10.1%) | 0.315 |

| Pain in the breast | 187 (67.3) | 207 (58.0) | −9.3% (−16.8% to −1.8%) | 0.017* |

| Nipple discharge | 207 (74.5) | 258 (72.3) | −2.2% (−9.2% to 4.7%) | 0.536 |

| How much do you agree or disagree with the statements: Response reported ‘strongly disagree or disagree’b | ||||

| I would be too embarrassed to talk about any lumps or changes in my breasts with the GP/doctor | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 171 (61.5) | 212 (59.4) | −2.1% (−9.8% to 5.5%) | 0.587 |

| Disagree | 72 (25.9) | 98 (27.5) | 1.6% (−5.4% to 8.5%) | 0.661 |

| I would be worried about wasting the GP/doctor's time | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 159 (57.2) | 188 (52.7) | −4.5% (−12.3% to 3.3%) | 0.255 |

| Disagree | 78 (28.1) | 103 (28.9) | 0.8% (−6.3% to 7.9%) | 0.826 |

| My GP/doctor would be difficult to talk to about signs and symptoms of breast cancer | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 169 (60.8) | 199 (55.7) | −5.0% (−12.8% to 2.7%) | 0.201 |

| Disagree | 61 (21.9) | 108 (30.3) | 8.3% (1.5% to 15.1%) | 0.019* |

| I would be worried about what the GP/doctor might find | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 100 (36.0) | 111 (31.1) | −4.9% (−12.3% to 2.5%) | 0.195 |

| Disagree | 50 (18.0) | 86 (24.1) | 6.1% (−0.2% to 12.4%) | 0.063 |

| I would be scared to know I have breast cancer | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 86 (30.9) | 116 (32.5) | 1.6% (−5.7% to 8.8%) | 0.676 |

| Disagree | 46 (17.6) | 76 (21.3) | 3.7% (−2.5% to 9.8%) | 0.249 |

| Perceived number of women diagnosed with breast cancer each year who are over 70c | ||||

| 1 in 3 | 23 (8.3) | 51 (14.3) | 6.0% (1.1% to 10.9%) | 0.019* |

| Whether seen, heard or read any adverts, publicity or other types of information in the last couple of months focussing on the subject of cancerd | ||||

| Yes | 209 (75.2) | 261 (73.1) | −2.1% (−8.9% to 4.8%) | 0.555 |

- a Agreement included ‘it is probably a warning sign’ and ‘it is definitely a warning sign’. Other options included ‘it is definitely not a warning sign’, ‘it is probably not a warning sign’ and ‘do not know’ and ‘refused’.

- b Options included ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘disagree’, ‘strongly disagree’, ‘not registered with a GP’, ‘do not know’ and ‘refused’.

- c Options included ‘1 in 2’, ‘1 in 3’, ‘1 in 5’, ‘1 in 10’, ‘do not know’ and ‘refused’.

- d Options included ‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘do not know’.

- * Statistically significant p values (p < 0.05).

3.2 GP attendances

The rate of GP attendances for symptoms of BC was 19% higher during the post-campaign analysis period compared to the comparison period (RR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.01–1.39, p value = 0.033), a significant increase (see Table 4). The rate during the analysis period was not statistically different to that in the comparison (rate ratio [RR]: 1.15, 95% CI: 0.96–1.38; p value = 0.113).

| Metric | Type of symptom/referral/cancer | Comparison period (2017) | Analysis period (2018) | Difference in percentage | Rate ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP attendances | Breast symptomsa | 0.23 visits per practice per week | 0.26 visits per practice per week | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.37) | 0.113 | |

| 0.20 visits per practice per weekc | 0.24 visits per practice per weekc | 1.19 (1.01 to 1.39)c | 0.033*c | |||

| Urgent GP referrals | Suspected breast cancer | 6873 | 8450 | 1.23 (1.09 to 1.38) | 0.001** | |

| Breast symptom referrals | 2832 | 2926 | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.25) | 0.730 | ||

| Cancer diagnosed from urgent GP referral | Suspected breast cancer | 1598 | 1720 | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.15) | 0.034* | |

| Breast symptom referrals | 199 | 203 | 1.02 (0.84 to 1.24) | 0.842 | ||

| Cancer diagnoses in CWT database | All breast tumoursb | 2395 | 2721 | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.26) | 0.015* | |

| Malignant breast cancer | 2268 | 2531 | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24) | 0.035* | ||

| Breast carcinoma in situ | 127 | 190 | 1.50 (1.27 to 1.87) | <0.001** | ||

| Cancers diagnosed in the National Cancer Registration Dataset | Malignant breast cancer | 4135 | 4603 | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.22) | 0.017* | |

| Breast carcinoma in situ | 303 | 366 | 1.21 (1.04 to 1.41) | 0.015* | ||

| Early-stage at diagnosis | Malignant breast cancer | 80.8% (3023.25 of 3743.75 staged cancers) | 82.4% (3306.75 of 4014 staged cancers) | 1.63 | 0.065 | |

| Diagnostics in secondary care | Mammograms and ultrasounds | 41,140 | 47,090 | 1.14 (1.04 to 1.26) | 0.008** |

- a Breast symptoms defined as a breast lump; changes in the size or shape of the breast, the skin of breast or the nipple; nipple discharge; and pain in breast or armpit.

- b All breast tumours comprise malignant breast cancer and breast carcinoma in situ.

- c Post-campaign analysis period as defined in Table 1.

- * Denotes statistically significant (p < 0.05).

- ** Highly statistically significant (p < 0.01).

3.3 Urgent referrals for cancer and breast symptoms, and cancers diagnosed from an urgent referral

The rate of cancer referrals was 23% higher during the analysis period compared to the comparison period (RR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.09–1.38; p value = 0.001). The rate of breast tumours (malignant and in situ) diagnosed from an urgent cancer referral was 8% higher during the analysis period compared to the comparison (RR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.01–1.15; p value = 0.03).

There were no significant changes in the rate of referrals for symptoms (RR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.86–1.25; p value = 0.730) or breast tumours diagnosed from a referral for breast symptoms (RR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.84–1.24; p value = 0.842) between the two periods.

3.4 Cancer diagnoses in the Cancer Waiting Times (CWT) database

The diagnosis rates for all BCs, malignant and in situ BC in the CWT database were higher by 14%, 12% and 50%, respectively, in the analysis period compared to the comparison (all BC RR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.03–1.26; p value = 0.015; malignant BC RR:1.12, 95% CI: 1.01–1.24; p value = 0.035; in situ RR: 1.50, 95% CI: 1.27–1.87; p value = <0.001).

3.5 Cancers diagnosed in the National Cancer Registration Dataset

There were 468 more cases of malignant BCs and 63 more cases BC in situ diagnosed in the analysis period which represent 11% and 21% increases respectively (malignant BC RR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.02–1.22; p value = 0.017; in situ RR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.04–1.41; p value = 0.015).

3.6 Early-stage at diagnosis

The proportion of early-stage (TNM stage 1–2) cancers diagnosed in analysis period (82.4%) was not statistically different from that in the comparison period (80.8%) (p = 0.065).

3.7 Diagnostics in secondary care

The rate of mammograms and ultrasounds conducted was 14% higher in the analysis period compared to the comparison period (RR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.04–1.26; p value = 0.008).

3.8 Comparison to previous campaigns

Table S1 provides a comparison of symptom awareness and attitude to help-seeking metrics for all three national campaigns. There was a significant increase in the proportion of respondents who had seen, heard or read any adverts regarding cancer in the last couple of months for the first campaign only.

There was a positive impact on symptom awareness for the first campaign only. In contrast to the third campaign, the first and second campaign did not increase the accuracy of awareness of BC risk, in terms of the number of correct answers to the statements about breast cancer risk, for women over 70 specifically. The first and second campaigns had greater impact on respondents' attitudes towards help-seeking, with more respondents disagreeing with unfavourable attitudes. However, there was a decrease in respondents strongly disagreeing.

Table S2 provides a comparison of clinical metrics (all metrics apart from symptom awareness and attitudes to help-seeking) for all three national campaigns. The first campaign appeared to have the greatest impact on all metrics analysed, except for breast carcinoma in situ diagnosed; the RR was highest for the third campaign. The impacts of the second and third campaigns were attenuated but prevailed for most metrics.

The impact on urgent GP referrals for breast symptoms and cancers diagnosed from an urgent GP referral for breast symptoms was no longer statistically significant after the first two campaigns. There were no increases in the proportion of cancers diagnosed at an early stage for any campaign.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Clinical metrics

The third BCW70 campaign influenced urgent GP referrals for suspected BC, BC diagnosed from an urgent GP referral, BCs diagnosed and mammograms and ultrasounds performed. GP attendance for breast symptoms increased after the analysis period (during the post-campaign analysis period), suggesting a delayed, but unexpected, effect of the campaign on this metric. The main outcome of the campaign was an increase in urgent cancer referrals and diagnosed BCs.

There was an increase in urgent cancer referrals, suspected BCs diagnosed from such referrals and mammograms and ultrasounds performed across all three national campaigns, probably because more women were referred. However, increases observed after the first campaign diminished over subsequent campaigns. The reduced impact of the third campaign may be due to a lower media spend and no public relations activity, and diminished returns in the wake of the previous two campaigns. An increase in referrals (Bethune et al., 2013; Broggio & Francis, 2015; Kabir & Khoo, 2016; Lai et al., 2020) and cancers diagnosed from them (Broggio & Francis, 2015; Lai et al., 2020) have also been found for other BCoC campaigns. Increases in mammograms and ultrasounds were most likely due to increased referrals (and therefore attendance) to secondary care.

Unlike urgent cancer referrals, urgent referrals for breast symptoms were unaffected by the third campaign, despite increases after the first and second campaigns. This may be related to overall downward trends for these referral types, through changes in the referral guidelines from 2015 (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2021); furthermore, the two referral types are related, with a decision having to be made between the suspected BC and breast symptoms routes. Thus, increases in the referral route for suspected BC may partly stem from cases which might previously have been referred as breast symptoms. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that there was no effect on GP referrals for more general breast symptoms in the final campaign, despite an increase following the first and second campaigns.

As delays in presenting to the GP with symptoms are associated with lower survival (Richards et al., 1999), it is important to examine how campaign messaging should be tailored to improve GP attendance. A mixed-methods approach combining quantitative with qualitative methods would allow deeper exploration than survey data alone. Nonetheless, cancers diagnosed from urgent GP referrals for suspected BC increased over all three campaigns, though this diminished with successive campaigns. This suggests that the campaigns influenced GP referral patterns even though there was only a delayed increase in GP attendance rates after the campaign had ended. The increase in referrals indicates that GPs may have been receptive to the BCoC campaign. Thus, the campaign may have led to changes in GPs' behaviour, rather than more women coming forward for assessment. As much of the campaign took place in GP surgeries and was intended to alert to BC risk, this is understandable. Future research could explore this by assessing awareness of the campaign and its messages in GPs, before and after the campaign.

BC diagnoses increased across all three campaigns, in line with other BCoC campaigns (Lai et al., 2020). Breast carcinoma in situ diagnoses increased following the third campaign but not following the first or second campaigns. This may be because of the increase in mammography in the older age group. There was no evidence that the proportion of early-stage malignant BC diagnoses was affected by any of the three campaigns.

4.2 Symptom awareness and attitudes to help-seeking

Several changes were observed in relation to awareness of BC risk, symptoms and attitudes towards help-seeking from one's GP for BC symptoms. Regarding BC risk and age, following the third campaign, there was a significant increase in women who accurately estimated that one in three women over 70 were at risk of developing BC. Thus, the third campaign improved women's risk perception in this age group, especially when compared to the first and second campaigns, which did not influence risk perception.

In relation to recognising warning signs of BC, a significant decrease in recognition was observed for pain in the breast—not normally a symptom of BC, and rarely a cause for referral in the elderly—following the third campaign, but not for other symptoms. However, symptom awareness before the campaign was already high.

Attitudes towards help-seeking from the GP were unaffected by the third campaign, although as attitudes were positive to begin with for all campaigns, this finding is unsurprising. Given the lack of change in symptom awareness, the observed increase in GP attendances warrants further investigation. Concerns about talking to the GP about signs and symptoms of BC improved after the third campaign, and fewer women stated they had these concerns. Moreover, fewer women felt that they would not want to know, or be scared to know, if they had BC, indicating that there had been a slight increase in fear and/or denial of symptoms. Overall, attitudes towards help-seeking from GPs were still overwhelmingly positive, with 80%–90% of respondents not being worried about wasting their GP's time and not being embarrassed or afraid to see their GP for symptoms. However, denial, fear and negative attitudes towards GPs can act as barriers towards help-seeking for BC symptoms (Bish et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2011). As GP attendances for breast symptoms only increased following the second campaign, further research is needed to determine alternative methods of encouraging women to see their GP, particularly for those exhibiting fear, denial and/or concerns over contacting their GPs.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

The BCW70 campaign represents a substantial effort to raise public awareness and effect behaviour change. The campaign was designed in consultation with GPs and a panel of expert representatives from public health, primary and secondary care, the charity sector and academic research (Public Health England, 2020b).

The campaign affected several clinical metrics, as well as some aspects of public awareness of BC in women over 70. However, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the evaluation used existing routinely-collected datasets not specifically designed to address the research aims. Only two time points were considered, so the results must be interpreted with this in mind. Future campaigns may benefit from expert clinical advisory groups during conception and planning, to identify outcomes of most value, how to measure these reliably and how to assess changes in them. Second, clinical metrics may have been affected by clinical trials occurring at the same time as the campaign. For example, the NHS-led AgeX trial (Moser et al., 2011), which extended the age group of women invited for BC screening to include women aged 47–49 and 71–73, may have influenced BC diagnoses in the period covered by the three campaigns, as some of these women were perhaps diagnosed through screening who previously would have presented symptomatically to the GP. Third, behavioural factors may also have affected the results. Symptom awareness does not necessarily lead to (timely) GP attendance (Bish et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2011). For example, downplaying symptoms or prioritising life events over seeing a physician can lead to older women delaying symptom presentation to healthcare (Petrova et al., 2020). A BC diagnosis does not always result in treatment, as this may not always be clinically appropriate, or even wanted by the patient (Frenkel, 2013). A decision to treat should involve balancing of risk and benefit, considering relevant co-morbidities. Finally, no data were available on the duration of BC symptoms before seeing the GP, and whether this appointment was motivated by the campaign. If symptoms were present long before the campaign, there would have been no opportunity for an early diagnosis attributable to the campaign. However, even for women with BC, earlier treatment through being motivated by the campaign to seek help may have at least resulted in benefits such as improved quality of life—again, there are currently no data which would allow an investigation of this possibility.

4.4 Impact across all three campaigns

Examining the impact across all three campaigns, for some metrics—GP attendances, urgent GP referrals and suspected breast cancers diagnosed from these referrals—effects diminished with each successive campaign. This is corresponds to other BCoC campaigns (National Cancer Registration and & Analysis Service, 2018; National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service, 2020). Effects on other metrics—cancers diagnosed from urgent GP breast symptom referrals, and some of the cancer diagnoses in CWT database—diminished in the second campaign, only to increase again in the third campaign, although they did not return to post-first campaign levels. While the diminished effects of the third campaign may be partly attributable to the reduced budget and reduced reach, any effect the first campaign had on individuals would not be repeated for the same individual with each subsequent campaign. Those most receptive to the campaign messages are likely to have been influenced by the earlier campaigns, leaving fewer people for successive campaigns to influence, leading to diminishing returns due to saturation. More time between campaigns could have led to these reaching a new audience who had no breast symptoms when the previous campaign had run or had moved into the target age group between campaigns. Future work should therefore identify why some women were less receptive to the BCoC campaign messages than others.

As discussed above, denial, fear and negative attitudes towards GPs are potential factors for diminished effect (Bish et al., 2005; O'Mahony et al., 2011), but there may be others. Future campaigns should consider different methods to influence those who are more difficult to reach, and how to sustain the effects of the campaigns. Finally, while the positive findings are encouraging, these findings may have been influenced by factors that were not measured or assessed. Further research, using mixed methods to allow deeper exploration, is needed to determine causal relationships between campaigns such as the present one, and clinical and public awareness outcomes.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The third BCW70 campaign was associated with an increase in GP referrals, diagnostics in secondary care and malignant BCs and breast carcinoma in situ diagnosed, although GP attendance for breast symptoms was not significantly affected during the campaign. Examining all three BCoC BCW70 campaigns, their impact diminished successively, as is the case for other national BCoC campaigns. To maximise their chances of success in terms of increasing GP attendance, future campaigns should focus on harder-to-reach women, for example, those who react with fear, avoidance or denial to the campaign messages. Furthermore, targeting GPs in future campaigns may be useful, as the present campaign showed potential to influence their referral behaviour.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work uses data that have been provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. The data are collated, maintained and quality assured by the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service, which is part of Public Health England (PHE).

Statement on approval for the routinely collected health data: NDRS have legal permission to collect patient-level data and to use it to protect the health of the population. This permission is given under Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006. This work has been funded by a grant from Public Health England; however, the interpretation of the data, the discussion of it and conclusions drawn were all made independently of PHE by JE and JL.

The authors would also like to acknowledge the following individuals for their input into this research:

• Jennie Fergusson, Marketing Planning Lead and Peggy Gilbert, Senior Marketing Planning Manager at PHE who facilitated access to marketing results, answered author's questions and provided formative feedback on the early draft.

• Emma Logan and Karen Eldridge at PHE who delivered the campaign and contributed to the design of the evaluation.

• Kantar Public (https://www.kantarpublic.com/) who assisted in interpretation of the campaign evaluation data

• Dr David Dodwell who provided clinical feedback on the draft manuscript.

• Isobel Tudge, Catherine Welham, Kwok Wong NCRAS analysts who completed the initial analysis.

• Jodie Moffat who contributed to the design of the campaign and the original analysis through the BCoC Steering Group and provided formative feedback on the draft manuscript.

• Helen Hill (former BCoC Programme Manager) at PHE who facilitated improved drafts and provided administrative support and quality assurance.

• Past and present members of the Be Clear on Cancer Steering Group for their support and guidance throughout the lifecycle of the campaign and its evaluation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None disclosed.

APPENDIX A

| Breast symptoms | |

|---|---|

| Code | Description |

| 1424.00 | H/O: * breast |

| 1596.00 | H/O: breast problem |

| 1A8.00 | Breast lump symptom |

| 1A82.00 | Breast lump present |

| 1A83.00 | Breast lump detected by clinician examination |

| 1A84.00 | Breast lump detected by mammogram |

| 1A85.00 | Breast lump detected by partner |

| 1A86.00 | Breast lump detected by self-examination |

| 1A8Z.00 | Breast lump symptom NOS |

| 1A9.00 | Nipple discharge symptom |

| 1A92.00 | Nipple discharge present |

| 1A9Z.00 | Nipple discharge NOS |

| 26B4.00 | O/E—peau d'orange |

| 26B7.11 | Breast irregular nodularity |

| 26B7.12 | Lumpy breasts |

| 26BA.00 | Deformation of breast |

| 26BB.00 | Contour of breast distorted |

| 26BD.00 | Intractable breast pain |

| 26BH.00 | Breast tenderness |

| 26C2.00 | O/E—retraction of nipple |

| 26C2.11 | O/E—retracted nipple |

| 26C3.00 | O/E—cracked nipple |

| 26C3.11 | Sore nipple |

| 26C3.12 | Painful nipple |

| 26C4.00 | Nipple eczema |

| 26D..00 | O/E—nipple discharge |

| 26D1.00 | O/E—no nipple discharge |

| 26D2.00 | O/E—nipple discharge—clear |

| 26D3.00 | O/E—nipple discharge—milky |

| 26D4.00 | O/E—nipple discharge—blood-red |

| 26D5.00 | O/E—nipple discharge—blood-dark |

| 26D6.00 | O/E—nipple discharge—pus |

| 26DZ.00 | O/E—nipple discharge NOS |

| 26E..00 | O/E—breast lump palpated |

| 26E..11 | O/E—breast lump position |

| 26E2.00 | O/E—breast lump—nipple/central |

| 26E3.00 | O/E—breast lump—upper in-quad |

| 26E4.00 | O/E—breast lump—lower in-quad |

| 26E5.00 | O/E—breast lump—upper out-quad |

| 26E6.00 | O/E—breast lump—lower out-quad |

| 26E7.00 | O/E—breast lump—axillary tail |

| 26EZ.00 | O/E—breast lump palpated NOS |

| 26F..00 | O/E—breast lump size |

| 26F1.00 | O/E—breast lump—pea size |

| 26F2.00 | O/E—breast lump—plum size |

| 26F3.00 | O/E—breast lump—tangerine size |

| 26F4.00 | O/E—breast lump—orange size |

| 26FZ.00 | O/E—breast lump size NOS |

| 26G..00 | O/E—breast lump consistency |

| 26G1.00 | O/E—breast lump soft |

| 26G2.00 | O/E—breast lump cystic |

| 26G3.00 | O/E—breast lump hard |

| 26GZ.00 | O/E—breast lump consist. NOS |

| 26H..00 | O/E—breast lump regularity |

| 26H..11 | O/E—breast lump—outline |

| 26H1.00 | O/E—breast lump smooth |

| 26H2.00 | O/E—breast lump irregular |

| 26HZ.00 | O/E—breast lump regularity NOS |

| 26I..00 | O/E—breast lump tethering |

| 26I1.00 | O/E—breast lump not tethered |

| 26I2.00 | O/E—breast lump fixed to skin |

| 26IZ.00 | O/E—breast lump tethered NOS |

| 6862.00 | Breast neoplasm screen |

| 7131211 | Lumpectomy of breast |

| 7131300 | Wire guided excision of breast lump under radiology control |

| 7131600 | Wire guided wide local excision breast lump radiology control |

| 7131B11 | Lumpectomy NEC |

| 7136300 | Reconstruction of the nipple or areolar complex unspecified |

| 7136500 | Eversion of nipple |

| 7N12.00 | [SO]Breast |

| 7N12100 | [SO]Upper outer quadrant of breast |

| 7N72000 | [SO]Skin of breast |

| 9OHE.00 | Patient breast aware |

| K300.00 | Solitary cyst of breast |

| K312.00 | Fissure of nipple |

| K312.11 | Cracked nipple |

| K317.00 | Breast signs and symptoms |

| K317000 | Mastodynia—pain in breast |

| K317011 | Breast soreness |

| K317100 | Lump in breast |

| K317111 | Breast mass |

| K317200 | Induration of breast |

| K317300 | Inversion of nipple |

| K317400 | Nipple discharge |

| K317500 | Retraction of nipple |

| K317700 | Skin thickening of breast |

| K317z00 | Breast signs and symptoms NOS |

| K31y.00 | Other breast disorders OS |

| Kyu7100 | [X]Other signs and symptoms in breast |

| R022.00 | [D]Local superficial swelling, mass or lump |

| R022200 | [D]Lump, localised and superficial |

| R022600 | [D]Localised swelling, mass and lump, multiple sites |

| R022700 | [D]Axillary lump |

| R022z00 | [D]Local superficial swelling, mass or lump NOS |

| R066.00 | [D]Swelling, mass and lump of chest |

| R066100 | [D]Chest lump |

| R066z00 | [D]Swelling, mass or lump of chest NOS |

| Control: Back Pain | |

| 16C..00 | Backache symptom |

| 16C2.00 | Backache |

| 16C3.00 | Backache with radiation |

| 16C4.00 | Back pain worse on sneezing |

| 16C5.00 | C/O—low back pain |

| 16C6.00 | Back pain without radiation NOS |

| 16C7.00 | C/O—upper back ache |

| 16C8.00 | Exacerbation of backache |

| 16C9.00 | Chronic low back pain |

| 16CA.00 | Mechanical low back pain |

| 16CZ.00 | Backache symptom NOS |

| 1D24.11 | C/O—a back symptom |

| N12..13 | Acute back pain—disc |

| N141.11 | Acute back pain—thoracic |

| N142.11 | Low back pain |

| N142.13 | Acute back pain—lumbar |

| N143.11 | Acute back pain with sciatica |

| N145.00 | Backache, unspecified |

| Ultrasounds | ||

| NICIP | UMAMB | US Breast Both |

| NICIP | UMAML | US Breast Left |

| NICIP | UMAMR | US Breast Right |

| SNOMED | 47079000 | US Breast |

| SNOMED | 47079001 | US Breast |

| Mammograms | ||

| NICIP | XMAMB | XR Mammogram Both |

| NICIP | XMAML | XR Mammogram Left |

| NICIP | XMAMR | XR Mammogram Right |

| SNOMED | 43204002 | Bilateral Mammogram |

| SNOMED | 572701000119102 | Mammogram Left |

| SNOMED | 566571000119105 | Mammogram Right |

| SNOMED | 71651007 | Mammogram |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data subject to third party restrictions: Data were extracted from datasets held by public bodies and commercially collected data. The data that support the findings of this study are row level and can be requested via the Data Access Request Service (DARS) or Office for Data Release (ODR) from the data sources/organisations where the data are held: The Health Improvement Network, the National Cancer Waiting Times Monitoring Data Set, the National Cancer Registration Dataset and the Diagnostic Imaging Dataset. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for this study. Data are available with the permission of these organisations.