The relationship between meaning discrepancy and emotional distress among patients with cancer: the role of posttraumatic growth in a collectivistic culture

Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between meaning discrepancy and emotional distress (i.e. anxiety and depression) among patients with cancer in a collectivistic culture, and to explore the stress-buffering effect of posttraumatic growth on this relationship. We collected data from 198 patients with cancer who completed questionnaires measuring meaning discrepancy, posttraumatic growth, anxiety and depression. Correlation analyses indicated that meaning discrepancy positively correlated with anxiety (r = 0.477, P < 0.01) and depression (r = 0.452, P < 0.01). Three structural equation models were built to compare competing hypotheses. Results showed that the moderation model fits the data better than the mediation and independence models (χ2/df = 1.31, RMSEA = 0.040, CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.92). The present study demonstrated a positive association between meaning discrepancy and anxiety/depression, and a protective effect of posttraumatic growth on mental health by buffering traumatic stress. The study has clinical implications for the medical practice of oncology; doctors, nurses, relatives and counsellors should attend to the psychological care of patients with cancer by exploring their meaning discrepancy, and promoting the use of posttraumatic growth as a psychological resource to buffer the anxiety and depression of patients with cancer.

Introduction

Cancer is one of the fatal diseases, and its prevalence rate has increased in recent years. In 2012, the worldwide burden of cancer rose to an estimated 14 million new cases per year, a figure expected to rise to 22 million annually within the next two decades, and China had the highest death rate from cancer among the countries that were studied in 2012 (Stewart & Wild 2014). A diagnosis of cancer undoubtedly is a threat to most individuals as it reminds them that they face the possibility of death (Arndt et al. 2007). The chronic and painful aspects of the treatment process constitute a major trauma for patients, worsening an already stressful experience. The threatening nature of the situation triggers persistent worry about the prognosis, side effects of treatment and fear of relapse (Salsman et al. 2009; Sumalla et al. 2009). All of these factors aggravate the psychological trauma of patients with cancer, and induce a series of psychological states of distress, such as anxiety, depression, low life satisfaction and quality of life (Salsman et al. 2009; Park et al. 2010). Meta-analyses including 30 studies identified the prevalence of depression to be 16.5% and anxiety disorders to be 9.8% among cancer patients (including breast cancer, head/neck cancer and lung cancer) (Mitchell et al. 2011).

In the collectivistic culture of China, there has been increased attention to the psychological care of individuals being treated for cancer. However, until recently, the psychological care provided has been limited to informational and emotional support (Liu et al. 2005), or to the philosophy of Chinese medicine (Xu et al. 2006). Most patients with cancer and their family members, even their doctors and nurses, deliberately avoid discussing the effects of their cancer on their belief system, for example, feeling of the world being unfair. This practice, in part, is due to the social demand that the patients must be resilient when coping with stress and show concern for others in the collectivistic culture (Tong et al. 2012). However, behind the persona of ‘revolutionary optimism’, there is a sense of helplessness, hopelessness and loneliness deep in their hearts (Higginson & Costantini 2008). This type of socially desirable response interferes with cancer patients’ search for meaning; it actually underestimates the human being's potential to marshal positive mental resources, and it hampers the positive role of posttraumatic growth (PTG) in coping with the daily stressors of cancer.

Researchers have reported that when facing trauma and loss, one of the important tasks for individuals is to understand the traumatic event and the meaning that it has for themselves (e.g. Steger & Kashdan 2007; Gan et al. 2013). Meaning refers to the assessments of both the reality of what has happened and of the extent of the victim's suffering (Janoff-Bulman & Frantz 1997), which also results in feelings of irretrievable loss, anger, betrayal and helplessness. When individuals are threatened by an enormous trauma, the role of meaning and their search for it becomes a predominant focus in their lives (Park & Folkman 1997; Park 2008). Meaning making refers to a shift of a person's world view after a traumatic event such as a cancer diagnosis. This process can result in positive psychological outcomes, such as PTG (Cordova & Andrykowski 2003; Bussell & Naus 2010).

For instance, when patients with cancer cope with their disease, their meaning system, including their world view and personal values, are challenged severely (Holland & Reznik 2005). They are overwhelmed by feelings of uncertainty, fragility, fear and despair, and they are eager to search for meaning and hope in their illness and in their lives (Halldórsdóttir & Hamrin 1996; O'Connor 2002). If the patients can manage the overwhelming feelings and eventually benefit from the adversity, then PTG should occur. Therefore, in recent years, researchers have focused an increased amount of attention on the role of meaning making in the psychological adjustment of individuals with cancer (e.g. Park 2010; Sherman & Simonton 2012; Guo et al. 2013). These results, certainly, will have rich implications for the psychological care of patients with cancer.

Meaning and meaning discrepancy

Based on the meaning-making model proposed by Park (2008, 2010), an individual in a stressful situation will appraise the meaning of the event. In the present study, we use the term meaning discrepancy to refer to the difference between the situational or appraised meaning of an event and its global meaning. Park (2010) defined meaning as the perceived importance of a life event, and differentiated between two types of meaning: global meaning and situational meaning (Park & Folkman 1997; Park 2008, 2010). Global meaning refers to individuals’ general meaning system (Park & Folkman 1997; Park 2010), which is developed by the accumulation of chronic life experiences (Catlin & Epstein 1992; Park & Folkman 1997). Situational meaning is the appraisal of the meaning of a stressful event, which is generated when an individual is contextualised in a certain situation (mainly a stressful life event). Later, Park (2010) proposed that the discrepancy between global meaning and situational meaning is an important factor in post-traumatic adjustment, that is, the manifestation of psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, as well as PTG.

According to the meaning-making model, the magnitude of meaning discrepancy determines the degree of stress that the individual perceives. If there is no meaning discrepancy, the individual is capable of coping with the stressful situation successfully (Park & Folkman 1997; Davis et al. 2000). However, if meaning discrepancy exists, psychological distress will be induced, resulting in meaning making among these individuals, in particular, cancer patients (Tomich & Helgeson 2004; Park et al. 2008). The individual's meaning-making process will reduce meaning discrepancy by finding meaning and, thus, facilitate psychological adjustment (Park & Folkman 1997). Thus, PTG can occur concurrently with depression and anxiety (e.g. Cordova et al. 2007).Therefore, minimising meaning discrepancy is regarded as an effective way of promoting psychological adaptation (Greenberg 1995; Lee et al. 2004; Collie & Long 2005; Skaggs & Barron 2006).

Park (2008) conducted a survey to examine the relationship between meaning discrepancy and psychological adjustment. Cross-sectional data from the study supported a significant association among meaning discrepancy, depression, states of mind and stress-related growth. Furthermore, she used the difference scores on meaning discrepancy to represent the meaning change, and found that the decrease in meaning discrepancy was positively associated with positive affect and negatively correlated with depression and negative affect. However, De Ridder and Kuijer (2007) found an inconsistent correlation between the goal difference dimension of meaning discrepancy and well-being. In view of these results, we assume that there exists a moderator between meaning discrepancy and psychological adjustment, which contributes to the inconsistent association between them.

Competing models of the functioning pathways of PTG

A substantial amount of research has found that while cancer as a traumatic life event negatively affects mental health, it also can result in positive psychological outcomes, such as PTG (Cordova & Andrykowski 2003; Morrill et al. 2008; Bussell & Naus 2010; Silva et al. 2012; Danhauer et al. 2013). PTG refers to the positive changes experienced by individuals who have undergone major life events that are stressful. It is characterised by five features: discovery of new possibilities, improvement of interpersonal relationships, strengthening of personal power, appreciation of life and changes in spirituality (Tedeschi & Calhoun 1996, 2004). Researchers found that PTG occurred in a longitudinal study of patients with leukaemia after psychological trauma, and that it tended to increase among the patients with the passage of time (Danhauer et al. 2013).

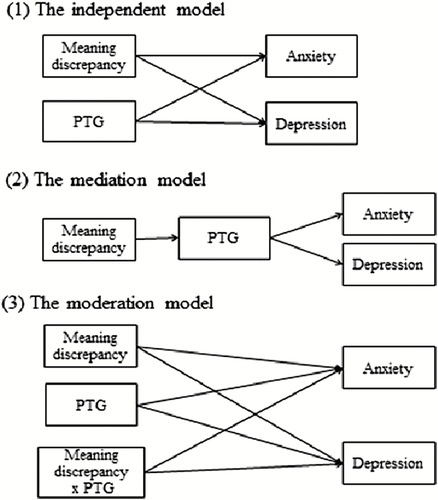

In previous research on patients with cancer, we observed two pathways of positive effects of PTG. First, PTG directly facilitates psychological adjustment by promoting a sense of well-being (Schwarzer et al. 2006), reducing distress and depression (Carver & Antoni 2004), and increasing positive affect (Bower et al. 2005). However, the effect of PTG on psychological adjustment is neither stable nor consistent (Tomich & Helgeson 2004; Lechner et al. 2006). Second, to explore the boundary condition of PTG on psychological adjustment, the stress-buffering effect of PTG was proposed (Cohen & Wills 1985; Pakenham 2005; Park et al. 2010; Silva et al. 2012). That is, PTG may interact with other variables to buffer the negative effects of stress. Based on the research findings noted earlier, we have proposed three competing models to depict the effects of the PTG: (1) a mediation model, (2) an independence model and (3) a moderation model. Please refer to Figure 1 for details of the three models.

Three hypothetical models: the independence model, the mediation model and the moderation model.

The mediation model: meaning discrepancy → PTG → anxiety/depression

In the mediation model, meaning discrepancy affects anxiety and depression through the mediating effect of PTG. According to Park's meaning-making model, when individuals perceive meaning discrepancy, they will engage in meaning making, and successfully deal with stressful events by finding meaning (meaning made) in the events that they have experienced (Park 2008, 2010). PTG may occur when one perceives a threatening event or disease, as in the case of patients with cancer (Cordova et al. 2001), and it correlates significantly with the person's subjective appraisal of the threatening disease (e.g. Sears et al. 2003; Bellizzi & Blank 2006). Park (2008) confirmed that PTG, as a form of meaning made, mediated the relationship between meaning making and psychological adjustment. Therefore, we hypothesised that PTG acts as a mediator between meaning discrepancy and anxiety/depression as one of the competing models.

The independence model: meaning discrepancy + PTG → anxiety/depression

In the independence model, we assume that meaning discrepancy and PTG have direct and independent effects on anxiety and depression. Meaning discrepancy and PTG have neither an interaction nor a sequential relationship. It was mentioned previously that after individuals perceive meaning discrepancy, they will strive for PTG through meaning making. However, other researchers have noted that meaning making has both adaptive value (e.g. Sears et al. 2003; Bower et al. 2005) and negative effects (e.g. Stanton et al. 2000). Meaning making does not necessarily lead to meaning made (e.g. Davis et al. 2000; Young & Foy 2013). In particular, few studies have found an association between PTG and the core belief system (Park & Fenster 2004). Therefore, we assume that meaning discrepancy does not lead to PTG; there is no sequential relationship between the two concepts.

The moderation model: meaning discrepancy × PTG → anxiety/depression

In the moderation model, PTG plays a moderating role in the relationship between meaning discrepancy and emotional distress. According to the stress-buffering mechanism, the protective role of PTG will become more significant when the stress level is high. In this condition, patients are capable of re-evaluating the stressful event by finding positive changes in life, thus alleviating the negative effect of the event on psychological adjustment. For instance, Morrill et al. (2008) demonstrated the positive role of PTG in preventing posttraumatic stress disorder and depression, and in improving the quality of life among patients with breast cancer. Park et al. (2010) found that PTG could cushion the negative impact of invading thoughts on positive affect, life satisfaction and well-being in middle-aged and young patients with cancer. In summary, PTG has been found to have a significant stress-buffering effect on the negative effects of cancer. Therefore, we hypothesise that in Park's meaning making model, PTG may have similar stress-buffering effects on the relationship between meaning discrepancy and anxiety/depression.

The present study

The present study aims to explore the effect and mechanism of meaning discrepancy on the psychological adjustment of patients with cancer, and to clarify the role of PTG by comparing different structural equation models. As mentioned in the Introduction, global meaning consists of beliefs and goals. Park (2008) observed that there was a lack of research attempting to examine how beliefs in global meaning influence psychological adjustment before her study in 2008. Therefore, we focused on the discrepancy between the belief dimension of global meaning and the situational meaning of the stressful event. Based on the rationales and literature presented previously, we hypothesised that meaning discrepancy would be positively related to anxiety/depression. In addition, PTG would play a critical role in this relationship. We planned a comparison of three competing models, that is, the mediation, independence and moderation models, to represent the role of PTG. Based on our literature review, we predicted that the moderation model would show the best fit to the data.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The participants were 198 Chinese patients who were diagnosed with cancer. The mean age was 57.70 years (SD = 12.11, range = 23–82). The participants were required to meet the following criteria for inclusion in the study: (1) a diagnosis of cancer (time since diagnosis: M = 28.81 months, SD = 47.36), (2) the absence of a psychiatric condition traceable in the medical history, (3) the absence of a major visible disabling condition and (4) at least 18 years of age. Eligible patients were identified by their doctors while they were receiving cancer treatment in the hospital, or by members of a Cancer Rehabilitation Association. Participants were assured that their participation in the study was on a voluntary basis and that it would not affect their treatment or their access to other resources in the hospital. All of the participants signed informed consent forms prior to the completion of the questionnaires. Brief psychological counselling or referrals were provided after participation to a few participants who felt discomfort or expressed such desires while completing the questionnaire.

Measures

Meaning discrepancy

The questionnaire on meaning discrepancy, which was based on Park's studies (Park 2005, 2008), was designed specifically for this investigation to assess the extent to which patients appraised the disease as discrepant with their global beliefs. Examples of the instrument's questions include ‘Now, how much does the disease violate your sense of the world being fair or just'? and ‘How much does the disease violate your sense that the world is a good and safe place'? The scale contains five items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 for ‘not at all’ and 5 for ‘very much’). A higher score indicates a larger meaning discrepancy. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.76.

PTG

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; Tedeschi & Calhoun 1996) was used to assess the patients’ perception of positive life changes because of having cancer. The Chinese version of the scale was used in this study, revised by Gao and Qian (2010). The 21 items are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (very much), with higher scores indicating higher levels of PTG. A sample item is ‘I appreciate the value of my life more’. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for the PTGI was 0.92.

Anxiety and depression

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond & Snaith 1983) consists of two subscales: anxiety and depression, both of which contain seven items. Participants responded using a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always), with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety or depression. Sample items are ‘Worrying thoughts go through my mind’ and ‘I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy’. Cronbach's alphas were 0.78 for anxiety and 0.70 for depression.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 19 (IBM) and Lisrel 8.8 (Scientific Software International, Inc). Descriptive statistics and frequencies were used to characterise the sample. An independent t-test was used to compare male and female patients on the study variables. Pearson's correlations were used to measure the associations between the study variables. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was performed to determine the role of PTG between meaning discrepancy and anxiety/depression. Finally, simple slope analysis was performed to explore further the buffering effect of PTG.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The socio-demographic data of the participants regarding gender, age, marital status, education, residence and monthly household income were obtained through the participants’ self-reports. We also collected cancer-related data; in particular, the participants’ diagnostic and treatment information, including the time since diagnosis, disease site, disease stage, type of cancer and treatment history. Those information is presented in Table 1.

| N (valid %) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 102 (51.5) |

| Female | 93 (47.0) |

| Marital status* | |

| Single | 8 (4.0) |

| Married | 177 (89.4) |

| Divorced/widowed | 8 (4.0) |

| Education* | |

| High school or less | 106 (53.5) |

| More than high school | 87 (43.9) |

| Residence* | |

| City | 155 (78.3) |

| Villages and towns | 36 (18.2) |

| Monthly household income (RMB)* | |

| ≤3500 | 45 (22.7) |

| 3500–5000 | 62 (31.3) |

| 5000–8000 | 43 (21.7) |

| 8000–15 000 | 25 (12.6) |

| 15 000–30 000 | 6 (3.0) |

| >30 000 | 7 (3.5) |

| Disease site* | |

| Digestive system (esophagus, intestinal, stomach and pancreas) | 70 (35.4) |

| Lung | 68 (34.3) |

| Breast | 29 (14.6) |

| Female genital system (ovary, oviduct and cervix) | 7 (3.5) |

| Lymph | 5 (2.5) |

| Chest and mediastinum | 4 (2.0) |

| Liver | 4 (2.0) |

| Male genital system (testis and prostate) | 3 (1.5) |

| Kidney | 3 (1.5) |

| Thyroid | 1 (0.5) |

| Abdomen | 1 (0.5) |

| Disease stage | |

| I | 10 (5.1) |

| II | 29 (14.6) |

| III | 58 (29.3) |

| IV | 84 (42.4) |

| Type of cancer | |

| Non-invasive | 85 (42.9) |

| Invasive | 99 (50.0) |

| Previous cancer treatment | |

| Surgery for this cancer* | |

| No | 61 (30.8) |

| Yes | 130 (65.7) |

| Chemical or radiation therapy for this cancer* | |

| No | 35 (17.7) |

| Yes | 156 (78.8) |

- *Variable containing missing information: gender (3, 1.5%); marital status (5, 2.5%); education (5, 2.5 %); residence (7, 3.5%); monthly household income (10, 5.1%); disease site (3, 1.5%); disease stage (17, 8.6%); type of cancer (14, 7.1%); had surgery for this cancer (7, 3.5%); had chemical or radiation therapy for this cancer (7, 3.5%).

Table 2 summarises the means, standard deviations and Pearson's correlations for the major variables measured in the study. With the exception of PTG, for which women scored higher (M = 66.52 ± 20.58) than men (M = 54.40 ± 22.70), t(193) = 3.89, P < 0.001, no gender differences were found for the remaining study variables.

| Control/outcome variables | M (SD) | Meaning discrepancy | PTG | Anxiety | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaning discrepancy | 11.04 (5.06) | – | 0.093 | 0.477** | 0.452** |

| PTG | 60.07 (22.42) | 0.093 | – | −0.030 | −0.255** |

| Anxiety | 3.77 (3.17) | 0.477** | −0.030 | – | 0.536** |

| Depression | 4.10 (3.47) | 0.452** | −0.255** | 0.536** | – |

- *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

- PTG, total score on PTGI.

ANOVA and correlation analyses also indicated that four of the demographic and cancer-related variables, including gender, age, time since diagnosis and chemical or radiation therapy were related to meaning discrepancy, PTG, and anxiety or depression. Therefore, these four variables were included as covariates in the subsequent regression analysis.

Mediation analysis

To provide preliminary evidence for the mediation model, the bootstrapping procedure (Preacher & Hayes 2008) and the corresponding SPSS macro were used to explore the mediating model. We set the bootstrap samples to 5000. The results revealed that the mediating roles of PTG between meaning discrepancy and both anxiety [Beta = −0.0044, SE = 0.0059, 95% CI (−0.0245, 0.0020)] and depression [Beta = −0.0191, SE = 0.0151, 95% CI (−0.0530, 0.0071)] were not significant, thereby rejecting the mediation model.

Hierarchical multiple regression results of the interaction effect

To provide preliminary evidence for the moderation model, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the interaction effect of PTG between meaning discrepancy and anxiety/depression. Table 3 summarises the results of the regression equations. The results revealed that PTG interacted with meaning discrepancy in predicting anxiety (ΔR2 = 0.027, P < 0.05). The model accounted for 24.2% of the variance in anxiety. Similarly, the interaction of meaning discrepancy and PTG significantly predicted depression (ΔR2 = 0.034, P < 0.01). The model accounted for 32.1% of the variance in depression.

| Predicting variables | Anxiety | Depression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | R2 | ΔR2 | F | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F | |

| Step 1: | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.081 | 0.028 | 1.301 | −0.031 | 0.022 | 0.990 | ||

| Age | −0.005 | 0.012 | ||||||

| Time since diagnosis | 0.036 | 0.044 | ||||||

| Chemical or radiation therapy | 0.003 | −0.053 | ||||||

| Step 2: | ||||||||

| Meaning discrepancy | 0.436*** | 0.202 | 0.173*** | 8.988*** | 0.447*** | 0.194 | 0.172*** | 8.552*** |

| Step 3: | ||||||||

| PTG | −0.133+ | 0.215 | 0.014 | 8.085*** | −0.333*** | 0.286 | 0.093*** | 11.840*** |

| Step 4: | ||||||||

| PTG × meaning discrepancy | −0.165* | 0.242 | 0.027* | 8.024*** | −0.186** | 0.321 | 0.034** | 11.861*** |

- +P≤ 0.06; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

SEM

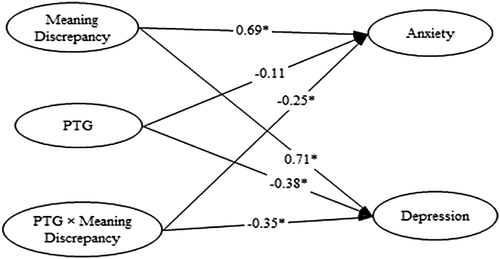

We performed SEM to compare the mediation, independence and moderation models. The fit indices are presented in Table 4. According to Hu and Bentler's (1999) criteria for model fit, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) must be less than 0.05, and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) must be greater than 0.95. Thus, the moderation model fits the best with the data. As presented in Figure 2, the meaning discrepancy × PTG interaction term predicted both anxiety and depression significantly. In the independent model, PTG predicted depression significantly, but the functional pathway of ‘PTG → anxiety’ was not significant. In the mediation model, both pathways of ‘meaning discrepancy → PTG’ and ‘PTG → anxiety’ were not significant.

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2 /df | CFI | GFI | RMSEA | 90%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderation | 146.86 | 112 | 1.31 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.040 | 0.018–0.056 |

| Mediation | 116.51 | 72 | 1.62 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.056 | 0.036–0.072 |

| Independence | 117.97 | 73 | 1.62 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.056 | 0.037–0.074 |

- The bold-faced model represents best fit.

Path model of the relationships between meaning discrepancy, PTG, meaning discrepancy × PTG, anxiety and depression. Note: Values indicate the standardised path coefficients.

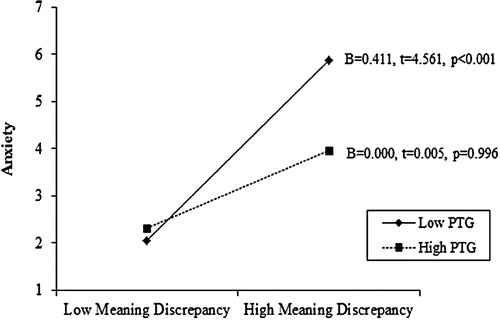

Simple slope analysis

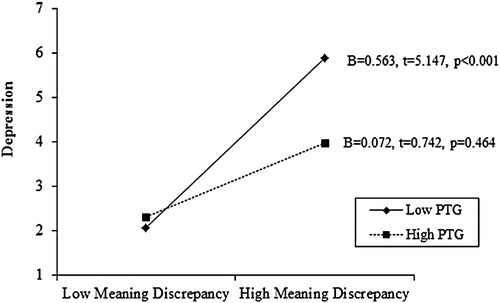

To visualise the two significant interactions, we plotted the points at one standard deviation above and below the mean of PTG. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the plots for the meaning discrepancy × PTG interactions on the dependent variables of anxiety and depression separately. Anxiety and depression did not vary significantly as a function of PTG when meaning discrepancy was low. However, when meaning discrepancy was high, the level of PTG was significantly associated with anxiety and depression. The post hoc analysis of the regression slopes plotted for anxiety and depression indicated that, among the patients with high levels of PTG, the slopes did not differ from zero (unstandardised B = 0.000, t = 0.005, p = 0.996; B = 0.072, t = 0.742, p = 0.464), but significant results were found for low levels of PTG (B = 0.411, t = 4.561, P < 0.001; B = 0.563, t = 5.147, P < 0.001). This suggests that for the patients with low PTG, anxiety and depression were found to be associated with meaning discrepancy. However, for the patients with high PTG, meaning discrepancy did not necessarily predict levels of anxiety and depression.

The moderating role of PTG on the links between meaning discrepancy and anxiety.

The moderating role of PTG on the links between meaning discrepancy and depression.

Harman one-factor tests to assess common method variance

Following the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2003), to limit and assess common method variance, we conducted Harman one-factor tests as a statistical remedy. The one-factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis revealed that the data did not fit the model well (RMSEA = 0.232, χ2/df = 11.60, CFI = 0.85); therefore, common method variance did not appear to be a significant problem in our study.

Discussion

This study sought to examine the relationship between meaning discrepancy and emotional distress, and to reveal its mechanism by exploring the role of PTG. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found a significantly positive correlation between meaning discrepancy and anxiety/depression. The greater the meaning discrepancy that the patients perceived due to cancer, the more likely they felt anxious and depressed. Furthermore, through the model comparison by SEM, we found that PTG was suggestive of a stress-buffering role in this relationship. When the patients demonstrated a high level of PTG, the association between meaning discrepancy and anxiety/depression was weakened; therefore, the protective role of PTG was manifested.

The relationship between meaning discrepancy and anxiety/depression

The current study provides a more comprehensive understanding of meaning discrepancy as one antecedent of anxiety/depression. Consistent with the finding of Scheffold et al. (2014), the perception of meaning discrepancy related to the diagnosis of cancer as a life threatening disease correlated significantly with the anxiety and depression symptoms reported by the patients. When individuals suffer major stress or traumatic events, they assign a meaning to these events, which is known as situational meaning. When a situational meaning threatens one's original belief system (i.e. global meaning), such as ‘the world is fair’, meaning discrepancy occurs, resulting in psychological distress in the individual (Koss & Figueredo 2004; Park 2008). Moreover, the degree of meaning discrepancy determines the level of psychological distress (Janoff-Bulman 1989; Park & Folkman 1997).

The stress-buffering effect of PTG

The present study found that when individuals encounter a major threat, such as cancer, emotional distress and psychological growth are likely to co-occur (Cordova et al. 1995, 2007; Sears et al. 2003). Based on theories and previous research, three competing models (i.e. the mediation model, the independence model and the moderation model) were compared to improve our insight into the functional pathways by which PTG affects anxiety and depression.

The hypothesis that the moderation model would show the best fit to the data was supported. By comparing the three competing models using SEM, the present study confirmed the moderating role of PTG, supporting the previous notion that PTG can be an adaptive psychological resource (Pakenham 2005; Siegel & Schrimshaw 2007; Morrill et al. 2008; Silva et al. 2012). When individuals suffer the discomfort caused by meaning discrepancy, the stress-buffering effect can act as a protective factor, which alleviates the negative influence of traumatic events to a certain degree.

In addition, as the simple slope test indicates, the protective effect can be manifested only when the level of meaning discrepancy is high. According to the definition offered by Janoff-Bulman and Frantz (1997), PTG can be regarded as an effort to understand the value or meaning of the traumatic event. Therefore, when the discrepancy between situational meaning and global meaning occurs, PTG helps individuals to redefine and reinterpret the fact of having cancer, and thereby facilitates the changes in their global meanings (Morrill et al. 2008; Silva et al. 2012). Thus, the discrepancy between situational meaning and global meaning is minimised, and the negative impact of meaning discrepancy on anxiety and depression is alleviated.

The mediation model, which states that PTG mediated the relationship between meaning making and psychological adjustment, was not supported by the data. This was because meaning discrepancy was not directly associated with PTG.

Depression and anxiety as indicators of the psychological distress of patients with cancer

This study attempted to incorporate more indicators of psychological health among patients with cancer. In previous studies, the stress-buffering effect of PTG focused mainly on positive psychological outcomes, such as the improvement in quality of life (Silva et al. 2012). It was not until recently that Park and her colleagues found that PTG could influence both the positive and negative effects of traumatic events (Park et al. 2010). Our retrospective data suggest that meaning discrepancy is related to an increase in depressive symptoms. This pathway is moderated by PTG. This is a stable finding consistent with previous studies (e.g. Morrill et al. 2008).

However, Silva et al. (2012) failed to find any buffering effect between the effects of disease and anxiety among patients with cancer. This finding was interpreted as anxiety being one of the many physical symptoms caused by disease and treatment, similar to pain, obesity or nausea, which cannot be alleviated by PTG. This notion was not supported by our study. Instead, we found that PTG did moderate the relationship between meaning discrepancy and anxiety.

This inconsistency could be attributed to a number of factors. First, the meaning making process was not taken into consideration when examining the role of PTG. Second, the demographic variables, such as the gender ratio, multiple types of cancer and the time from diagnosis to the time of the survey, and clinical conditions could cause the contrary result. This inconsistency suggests that there may be some boundary conditions for the stress-buffering effect of PTG (Park et al. 2010; Silva et al. 2012). An intensive investigation into the meaning making process and the demographic and clinical information should be useful in clarifying these boundary conditions.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

The limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the cross-sectional design limits the establishment of a causal relationship between meaning discrepancy and emotional distress. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether the stress-buffering role of PTG has long-term effects. Future research could assess multiple time points and further explore the causal relationships among the study's variables.

Second, as mentioned in the Introduction, global meaning consists of goals as well as beliefs, but we only assessed the violations of beliefs as a measure of meaning discrepancy. As mentioned in Park's (2008) study, violations of goals may be as important as, or even more important than violation of beliefs (Park & Folkman 1997; Emmons 2003), because the violation of goals may be even more powerful in generating distress (Austin & Vancouver 1996; Dalgleish 2004; Rasmussen et al. 2006). Therefore, future research on meaning discrepancy should take violation of goals into account as well.

Finally, the participants in our study were diagnosed with various types of cancer and their disease stages varied (ranging from I to IV), limiting the generalisation of our findings to any specific type or stage of cancer.

Implications

The present study provided a comprehensive assessment of the relationship among meaning discrepancy, PTG and anxiety/depression. Our results revealed a relationship between meaning discrepancy and emotional distress, described the pathways of meaning discrepancy and supported the buffering effect of PTG (Morrill et al. 2008; Park et al. 2010; Silva et al. 2012) based on a comparison among mediation, independence and moderation models.

The results of the current study have numerous implications for the practice of oncology. First, we chose to examine the antecedent of meaning discrepancy instead of perceived stress in our moderation model of PTG, not only for novelty but also for the rich implication of meaning discrepancy in cancer care. Meaning discrepancy may be regarded as a double-edged sword, as it may result in both psychological distress as well as a meaning-focused coping process (Park et al. 2010). Moreover, meaning discrepancy could, in a lager extent, be intervened than perceived stress. It seems encouraging to know that when individuals are faced with traumatic events such as cancer, their meaning discrepancy, which constitutes an important source of their anxiety and depression, may be included as part of the psychological interventions provided to them. Breitbart et al. (2010) conducted a pioneer intervention study that supports the use of meaning and meaning discrepancy in cancer patients. They discussed with individual cancer patients the development of their life's meaning, and which part of the meaning was challenged after the diagnosis of cancer.

Second, the current study found that PTG buffers the negative effects of psychological distress related to cancer. Therefore, it is necessary that doctors, nurses and relatives be aware of this psychological resource of the patients and offer sufficient opportunities for them to manifest their psychological growth. Finally, the promotion of PTG should be incorporated into the psychological interventions for patients with cancer during their cancer treatments.