Design Creativity in the Belly of the Beast

Abstract

C-K theory is about design creativity & innovation. Operational theory is about optimization and efficiency. C-K theory is about the search for the new in the unknown. Operational theory is about squeezing out inefficiency in the known. C-K theory works best under low pressure whereas operational theory works best under high pressure. C-K theory provides a framework for an exploration of a metaphorically unknown jungle whereas operational theory provides the procedures for traveling by public transport.

This paper addresses the challenging situation of applying design creativity within tightly organized operational processes. Processes are tightly woven organizational routines which resemble the parasympathetic system of our digestion that proceeds autonomously. How can we break in and make room for design creativity?

From a situational perspective on C-K theory, we then look at the theory of organizational routines. What are they and how are they created? These thoughts form the prelude to an exploration of the possible inclusion forces of routines, the forces that keep people within the behavior of the routines. Along the lines of a Deweyan inquiry, we look for integration of these elements to ultimately arrive at a proposal for resolution. Not easy, but fundamental.

Introduction

This paper addresses a situation that I have encountered for many years in my environment as an academic as well as I have this observed in the day-to-day practice of organizational life: the challenge to get people out their day-to-day routines in a mode of reflection and careful consideration of the situation at hand. Therefore, the title can be seen as an analogy of organizational routines that I compared to the parasympathetic movements of our digestive system: hence the processing processes of our organizations resemble the belly of our beasts we are part of.

We live in a world where routine behavior is efficient, economical, and thoughtful. Particularly within organizations, efficient routine behavior is important to be and, above all, to remain competitive. This is not just important for the operational processes, but equally for activities related to innovation. Companies have funnels and stage gates to make development processes not only effective, but also efficient. Activities such as market research, consumer research, concept testing, minimal viable products, prototyping and so on. Even these activities can be seen as routine activities because mature and robust companies have mastered this way of working very well over the years.

In this conceptual paper, we focus on those internal processes, how they came about and, above all, once they are in action, how does design creativity fit in there? The central question we want to address here is, how can design creativity find a place within those optimized and routine processes? This is especially the case when situations arise that actually require design creativity as an approach, but which also seem to be addressable with ‘firefighting’. Situations that deviate from the norm, that deviate from previous cases and that deviate from the daily routine might benefit from activities that help to move beyond addressing the symptoms.

However, amid the daily routines, it is especially important not to be distracted by things that do not seem to matter. This is necessary for economic feasibility and to achieve the associated performance indicators, often referred to as Key Performance Indicators (KPI). Thus, when an anomalous or doubtful situation arises, a tension arises between the feeling of not being able to respond to it without harming the targets and the feeling that there is a situation that somehow demands attention. A diabolical dilemma you could say.

The problem is that we do not know in advance whether the deviating situation (or weak signal) will indeed prove to be of importance or whether it will just be temporary (Repenning & Sterman, 2001). Do you allow yourself to be distracted and investigate what is going on, or do you continue with your work and achieve your targets. Of course, if a fire breaks out, you must react, but if there is only a strange smell, it may even be that people hardly notice it. Especially if that strange smell seems to have disappeared after a while. But what to do if that strange smell occurs more often and you are the only one who smells it and you become increasingly suspicious?

A questionable situation is starting to arise, as it were, a situation in which you do not feel comfortable and especially feel tension about how to act. In the words of pragmatism, we are talking about a doubtful situation here (Dewey, 1938). From a decision-making viewpoint it can also be seen as a moment to decide for one or the other. Are we going to sound the alarm, are we going to bring it up in a quiet moment or are we just going to carry on as if nothing is wrong… which might be the case … you simply don't know.

In this paper we take a closer look at such situations and discuss these from the perspective of C-K theory (Hatchuel & Weil, 2009) and from the force field of social dynamics that exerts an enormous force within routine behavior to stay within it, the so-called inclusion forces. The recent developments surrounding the 737 MAX at Boeing represent just one of the many situations that arise every day within organizations. These require adequate attention from those involved, but they often do not know how or do not dare to act. Sometimes with dramatic consequences.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we briefly discuss C-K theory from the point of view of the three transitions, disjunction, expansion, and conjunction. We philosophize on the one hand about the cognitive processes that play a role in these three transitions and on the other hand about the behavioral component that is important. The next part then discusses organizational routines and shows that these can be regarded partly as an individual theoretical framework of how the routine works and what one's own role is in it. Partly also to be regarded as a collective human framework that has grown over time towards an optimum of interrelated activities. This is followed by a section that aims to identify potential inclusion forces within the force field that exists among the actors that participate within organizational routines and that keeps them trapped.

Then, in the pre-last section, we will use the perspective of the Deweyan inquiry to integrate C-K theory and the routine development process into a picture that will help to further discuss the problem of design creativity within the daily dynamics of routines. The article ends by introducing a simple solution… that is challenging to implement, to say the least.

C-K theory

C-K design theory was introduced in 2003 by Armand Hatchuel and Benoit Weil. This happened at the ICED conference. We are now 20 years later, and C-K theory has become a strong theoretical notion among scientists, but also, it seems that C-K as a notion gets more and more traction among practitioners. Especially the idea, and here I speak from my own observations, that one can speak about two spaces: A space in which we can decide about an object whether it is true or false (logical status) and a space where we cannot decide for true or false (no logical status). In any case, not a well-founded statement. The first space is the space of Knowledge that we use every day. Knowing that something doesn't work is just as important as knowing that something does work, and both can be seen as knowledge residing in the so-called K-space. In the C-space it is completely different. There we are talking about Concepts, propositions, thoughts, ideas and, above all, about things of which we do not yet know whether they will be true at any time later (no logical status). Those two spaces really appeal to people in practice is my experience. It lands quite quickly if you have a conversation with practitioners from the perspective of the two spaces. For that purpose, I need to ‘play’ a bit with the theory and add a few things: the perspective of a continuum related to the two spaces, the perspective of socio-interactivity and the temporal dimension. In short, what happens over time among the various innovating actors while moving in and out the two spaces regarding the topics under development.

Practitioners immediately understand that something can be true for one person and undecidable for another. They also understand that the C & K extremes are not really a challenge in how to deal with each other, but that there are plenty of challenges in the midfield, where one group can make a C-statement that somehow (and sometimes implicitly) challenges the K-space of another group. What is particularly exciting in this midfield is when undecidable statements from one actor collide with decidable statements from another actor around a specific theme. Which can easily slide into well-known turf wars among the disciplines and departments in organizations.

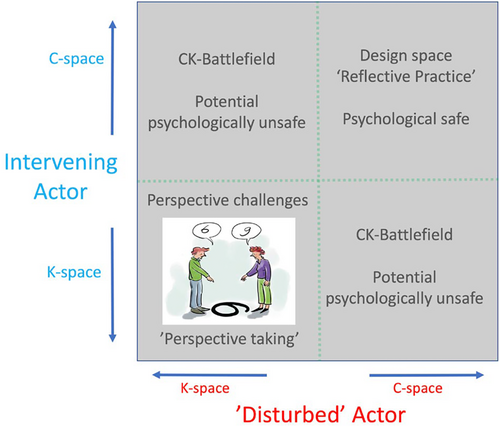

For the category of cases discussed in this paper there is an actor (or actor group) that intervenes the ongoing set of activities of another actor or group of actors. In this way we see a simple 2x2 matrix emerge that can help us to discuss the social and interactive dimension of interventions (Figure 1). On the left side we have the intervening actor(s) and on the bottom we find the ‘disturbed’ actor(s).

Clear is that the lower left quadrant is related to both actors being right, however each from their own perspective. For resolution such requires a synchronization process (Smulders, 2006) in which both actors aim to take the perspective of the other (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995) which could support the alignment of these two incompatible perspectives. Also, obvious that the upper right quadrant is the proper design space in which all actors involved, whether intervening or ‘disturbed’, at least agree on the situation as being undecidable. A collective reflective process as described by Donald Schön will support the design reasoning activities (1983).

Then the battlefield between actors having totally different opinions in terms of its true/untrue decidability regarding the subject at hand is found at the upper left and lower right quadrants. These are the areas where actors disagree on the state of affairs and may come into conflict. These two quadrants can therefore be seen as the social-interactive battlefield regarding C-K theory, from which, especially in the case of a power imbalance, psychologically unsafe situations can arise. Which will be discussed later.

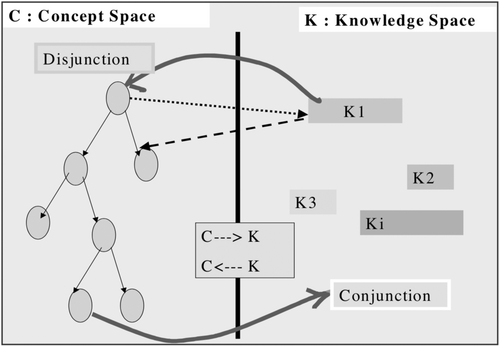

If we then take a time-dependent and situational perspective on C-K theory using the original graph (Figure 2), we see that these positions can shift and certainly do change.

Take, for example, the situation where there is a feeling at management level that there is a need for a new strategy with more focus on innovation. Leaving the safe-haven (organizational comfort-zone) with its existing and especially validated knowledge is necessary to arrive at new conceptual ideas. The adjusted or new business strategy is therefore the legitimation for such a step, the disjunction to the C-space. In the literature this is often referred to as the fuzzy front-end of innovation (Koen et al., 2001). The strategic search process in which the actors look for new insights, new starting points and, above all, ultimately for new opportunities for the company. So partly letting go of existing truths to create space for new insights and new opportunities. It remains to be seen whether these opportunities will also materialize, making it a typical C-space situation. We cannot say whether these initial ideas for opportunities will actually land in the market and actually generate business revenue. Perhaps even that a statement can be made about a facet of the idea, for example, that there is a validated need that the idea wants to respond to.

This shows that ideas, or objects, can have multiple layers or, if you prefer, multiple components. This observation refers to a well-known tool from the creativity world, the PMI approach (De Bono, 1982), which stands for, ‘P' what's good about the idea (plus); ‘M' what is less/not good about the idea (minus) and ‘I', what is interesting about it. In other words, a decomposition of an idea into several facets or components that can be assessed separately from each other, about which a statement can be made, or at least components that we can position over the C-K continuum. The P & M then fall somewhere in K-space and the I in C-space. And it will be clear that different actors can make different statements about each of those separate components. Think of the matrix shown in Figure 1.

Now we have briefly discussed C-K theory at the level of business strategy which legitimates (and forces?) the disjunction from the K-space. However, sometimes the disjunction from K-space to C-space is an accidental or sudden event. A serendipitous insight, an Eureka idea, a customer who calls with a problem, an accident in R&D, etc. In this paper the discussion is on events or observations that might have a negative (or positive) impact on the continuation of existing business operations and its associated organizational routines. Such becomes especially troublesome in the case of weak signals picked up by just a few actors. The next two sections will address the literature on organizational routines and how these are developed.

Organizational routines: what are they and how are they established

In this section we will look at how routine processes come about and what properties they have. We start from the perspective on organizational routines as defined by Feldman & Pentland (2003). According to these authors organizational routines consist of recognizable patterns of interdependent activities involving different actors.

This is not about the routine of one actor, but about how all the individual and complementary routines together form an integrated organizational routine. Think of a purchasing routine that starts performing from the moment a purchasing need arises within the organization for a certain product or service. The purchasing department then looks for a suitable supplier who can deliver the right quality at acceptable price and terms. As soon as this has been found and agreement has been reached on the terms of delivery (e.g. price, quality, quantity and time), the legal department draws up a contract to ensure that the supplier and customer adhere to the agreements. Finally, this routine includes a quality check on delivery of the items to the organization whether these fulfil the specifications drawn up in the contract.

This is a typical example of an organizational routine in which several interdependent activities are carried out by several (disciplinary) actors which follows a predefined pattern of activities. Such a routine has consciously and deliberately been developed by the organization, whether or not through trial and error; but for sure a process of organizational learning that have occurred over time. A similar reasoning or description applies to all organizational processes that occur regularly or even take place daily, such as in production.

Research that focused on discovering the ‘basic social process’ (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Glaser, 1992) between product developers and production people also revealed the transformation from a product concept on paper to a tangible operational volume production (Smulders, 2006): a performing organizational routine. We have learned that this transition consists of a number of overlapping stages, in which the product concept, which initially mainly exists on a drawing and in the minds of the designers, gradually transforms into an activity palette that, as it were, defines the underlying structure of the production process under construction and which in the end will form an organizational routine. In other words, the cognitive part related to the whole product, the product idea, is used as the basis for the transformation into ideas for production and assembly activities. And these ideas are then converted, tested and validated into actual actions by production people to build prototypes and later the zero-series. Prototyping the production process is used to develop a repertoire of actions that is effective and thus results in a product of the right quality. It is during this stage that engineering design changes related to the product or to manufacturing tools still occur. On the one hand to tackle matters related to product quality and on the other hand to improve matters related to production and assembly speed/quality. The switch to the 0-series takes place when it is suspected that the total effective set of actions can also become an integrated set of efficient actions, which is in fact the transition from C-space to K-space at the level of the entire production process. A fairly crucial step, because the 0-series will take place on the real production line, for which a lot of investments have already been made. Serious testing of the products from the 0-series forms the last step before going-life, starting the entire production chain with inbound and outbound logistics including sales and use by the end user.

Depending on the complexity of the product, perhaps only one product is assembled on the first day (or month), soon there will be more and more products per day (month). This period, which is called ramp-up, is in fact a major learning process and more or less conforms to laws as laid down in learning curves or experience curves (Terwiesch & Bohn, 2001). The more often an action is performed, the more efficient the actions become. And so is the interdependence among the various actions spanning the full operational (production) process. It is essential to understand that this is not just individual learning, how to perform the actions quickly and well, but also an intersubjective and reciprocal learning: how what actor ‘a’ does seamlessly fits with the actions of sequentially dependent actor ‘b’. This concerns a kind of ingraining of mutually coordinated actions that eventually and across the entire production system result in an organizational routine with ‘recognizable patterns of interdependent activities involving different actors’; hence, an organizational routine. One could say, that through mutual consultation and coordination, a practice-relevant mental framework is implicitly built that stands for the entire production system. And this knowledge is on the one hand in the heads of the production employees and on the other hand it is recorded in, for example, production molds and assembly procedures, and the design of assembly stations.

Smulders, in the aforementioned study (2006), speaks of a ‘noetic system', a system of concatenated individual but mutually deviating mental models, a kind of ‘human knowledge cloud’ that stands for the mental & behavioral side (knowing & doing) of the organizational routine. The notion ‘nous’, is Greek and stands for mind, understanding, etc., hence the use of the concept of ‘mental models’ (schemata).

Well, this is specific to (mass) production lines where many units are produced per day, which makes the interdependencies very visible. But think again about the routine that was briefly described earlier around the purchasing process. Here, too, interdependencies have been ingrained over time and have even become more or less implicit, meaning that sometimes we no longer know why we do what we do. It works and is efficient, and that applies to the existing situation, and therefore applies to the existing kind of work that goes through the many interrelated heads and hands. All those routines with associated procedures have become a noetic system and there is little room to organize the routine in a different way from one day to the next. Of course, adaptations on the micro-scale of an individual could easily occur, only if the output to others does not change. Even within one department this could (and will) happen. But as soon as multiple actors or even the collective of actors within the routine have to participate in the change, then in fact a new learning curve would have to be completed first; a new, practice-relevant theoretical framework must be developed containing the connected mental models of all those involved and serving as the underlying basis of the final new/adapted routine. We refer here to a practice-relevant theoretical framework because its users know this works and is predictive, although they might not know at scientific level why it all works. Such is still for science to uncover.

It is the concatenation of all these mental models within that noetic system that makes it difficult to bend the dynamics of an existing routine. The more people involved in an organizational routine, the more difficult it becomes to alter, change or adapt. It is not for nothing that people in this context speak of the metaphor of adjusting the course of crude oil tankers. But what holds all the actions of the separate contributing individuals together? What are possible ‘inclusion forces’? In the natural sciences the calculation of the forces that hold the separate parts of the oil tanker together is no problem; plenty of laws available for doing that. However, in the social sciences this is still a challenge and unchartered territory.

Towards inclusion forces: what forces keep actors trapped in K-space?

Now that we understand what routines are, what they consist of, and how they grow over time, this section explores the potential inclusion forces hidden in existing organizational routines. In analogical sense, organizational routines are like the parasympathetic movements of our digestive system as part of our body. That is an autonomous system that continues without us having to pay attention to it. But it doesn't stop at small anomalies either. Our digestive system, the belly of the beast, represents all routine processes within organizations. And as mentioned, this also concerns innovation routines. Let's look at the elements that could make up the force field that keeps people within the existing repertoire of actions and prevents them from responding adequately to weak signals.

First, we are talking about a theoretical framework that is scattered over all the participants' heads, but together forms the routine (noetic system). The actors have very consciously contributed to the routine as it is at the end, including the underlying practice-relevant theoretical framework. To be effective and efficient, it has been well thought out, logical steps and logical relationships have been developed, decisions based on facts and observations have been taken, alternative ideas have been dropped (Dorst, 1997), etc. The organizational routine has been designed and ‘robustinized’ (Smulders, 2014)! The result is a solid (theoretical) framework of well-considered decisions to which all the actors involved have contributed. Perhaps not as a collective, but certainly with smaller intersections of actors from adjacent disciplines. Newcomers, actors who join the organization later, have adapted to the part of the routine that their department is involved in. However, they will know and understand much less about how these different subroutines are interrelated and why. They will also not have a clear picture of the whole routine.

Second, not all knowledge from that framework has been explicit and discussed with actors from other disciplines. This concerns, for example, specific actions within a discipline that (apparently) have little influence on actions in other disciplines. This may also apply to assumptions within disciplines about how to perform their work optimally and efficiently. The situation in which routines have existed for years (decades) and are adapted, improved and made more efficient locally (departments), reinforces this hidden effect: at a certain point no one knows anymore why the procedures and agreements are the way they are.

Thirdly and summarizing, the existence of a noetic system in a performing state implies that there is a certain social-interactive momentum within which the relevant actors have a fixed role to play with predictable results and within given time frames. The underlying rationales of the relationships between the different disciplinary/departmental roles have disappeared from view over time, but the individual disciplinary activities that have little or no influence on the whole will have moved with the times and appear modern and logical to newcomers. This has created a certain collective and especially implicit mindset that is aimed at maintaining the ‘performing state’ of the organizational routine. In other words: the actors have little to no access to the causality of the underlying (theoretical) framework where interdisciplinary relations are concerned, but they are in their own disciplinary environment (bubble) that is apparently modern, current and logical. These disciplinary ties work (implicitly) as chains that keep them trapped within that part of the noetic system. That is their comfort zone … and that partly determines their future.

The consequence of these observations or characteristics of an organizational routine is that an organizational routine proceeds autonomously as if it were a parasympathetic system such as the digestive system in our body. Once it starts, it is almost impossible to stop. All separate steps are quite logic and adequate within the limited perspective of one or perhaps two disciplines, but the underlying rationales have disappeared from sight. Only large deviations from the norm and anomalies that are completely outside the system can stop the autonomous processes. For the first category, think of jammed production lines and for the second category, a hazard from outside the organization, fire, earthquake, or bankruptcy. In these situations, it is not difficult to stop the routine because it is immediately clear to all actors what is going on. In the case of jammed production line, another known and pre-developed routine will be set in motion.

Let us look at the situation of weak signals. If a few actors or just one actor perceives or feels something that requires further investigation, we speak of a weak signal. The question then arises, what are the possibilities to investigate this potentially important anomalous situation? This is especially important if the anomalous situation occurs more frequently and there are stronger suspicions that something may be (dramatically) wrong. But what exactly is going on may not be so clear. We are talking here about so-called weak signals, which in the literature mainly concern the market (e.g. Ansoff, 1975; Prahalad, 1995; Schoemaker & Day, 2009; Holopainen & Toivonen, 2012), but in our case these are signals that are related to existing organizational routines. Think of the whistleblowers within Boeing.

The characteristic of a weak signal is that it does not yet have a rationale, no explanation, let alone it is clear where it comes from. In other words, there is no direct relationship between the weak signal, its source and a possible consequence for the existing routine or worse. And certainly not with the logic behind the routine. Still, the kind of weak signals we're talking about here gives an uncanny feeling, a feeling that John Dewey calls a doubtful situation. A situation that is inconclusive, so that no statement can be made about it. A clear C-space situation, but only if the actors respond to the doubtful situation and look for its cause and are willing to enter C-space … and not rationalize or ‘judge’ it away in terms of, “we've never had any problems, so why …”.

Deweyan inquiry as means of integration

The aim of this section is to integrate the previous sections to problematize the situation of K-space escape and thus make it suitable for practice-oriented scientific research. We will do this using the tradition of pragmatism as developed in the last century by Dewey (1938) and recently upgraded to a handy perspective for practice-oriented research. But first a brief description of a Deweyan approach as developed by Stompff and colleagues (Stompff et al., 2022).

Let's assume that one or more actors working within an organizational routine are regularly confronted with a signal that was hardly noticed the first time, but still leads to an uncanny feeling because of its recurring nature. They will ask themselves: Why does this happen, and could there be something going on that may have unpleasant consequences?

This situation causes unrest on the one hand and on the other hand there seems to be little harmful things going on since at the moment it doesn't affect their job. Reasoning from the unrest situation, a doubtful situation in Dewey's terminology, we don't really know what to do. This is where the inquiry starts with the aim of turning the uncanny situation into a clear situation so that we know where we stand and also what we can do to overcome the uncanny feeling. This involves developing targeted interventions that will help us with this. The first set of interventions focuses on understanding the causes of the uncanny feeling, a sense-making process aimed at understanding what might be going on (Weick, 1995; Stompff et al., 2016). Lorino (2018) puts it very nicely as intellectualizing the uncanny feeling by understanding which factors play a role in this and what possible sources are, so what causes the actual observed things.

The situation requires a process that can actually be seen as a kind of exploring the problem space without immediately looking for solutions. First create a deep understanding of the situation and how it may have arisen (sense-making [Weick, 1995]) in such a way that a co-evolutionary process between the problem and solution spaces more or less automatically arises (Dorst & Cross, 2001). Everything aimed at converting the doubtful situation from the start into a solution-oriented activity.

Let's leave the Deweyan inquiry here and go back to the weak signals that occur within the organizational routine and that cause an uncanny feeling among one or more people involved. As indicated, the feelings that something is not quite right create a dilemma for the actors involved. Either they continue within K-space as if nothing wrong is going on, or they also try to initiate an inquiry in C-space. This by convincing the management and other participants of the routine of the uncanny feeling … a feeling that does not yet contain any rationality nor is it based on hard data, a typical undecidable situation. These soft, ambiguous, and intuitive thoughts must therefore create attention in a world that is dominated by validated rationality of every day's work. It is these novel events that don't fit in existing failure categories that might play important roles in disasters (Rudolph & Repenning, 2002). The situation here described seems to be connected to a range of psychological and cognitive factors that aim to suppress these observations when it could jeopardize organizational goals & targets (e.g. Shrivastava, 1987; Vaughan, 1996). But also factors like psychological safety are in play here (Edmondson, 1999; Edmondson et al., 2001). For instance, in engineering cultures there seems to be a dominant behavioral treat not to let anyone know that you are actually unsure about a specific situation, let alone that you aim to initiate a discussion on such uncanny feelings. Roth & Kleiner after investigating the car industry conclude: “There is a basic cultural commandment in engineering – don't tell someone you have a problem unless you have the solution.” (Roth & Kleiner, 1999,15–16). Amy Edmondson in discussing the accidents with Boeing's 737 MAX mentions “The trouble is, we are attuned mostly to interpersonal risk” (Edmondson, 2019), meaning that we don't want to disturb the organizational routine in favor of our own ‘comfort’. This might be especially the case in ambiguous situations that have no clear source of data, nor clear reasoning of what is happening, and even, no clear trajectory to an accident that might not even happen.

So, the question becomes, how to escape this dilemma. And why is Dewey and its inquiry mentioned here? Well, two things. First, practice-based research has shown that it does make sense to intervene in ongoing situations along the lines of a Deweyan inquiry to make sense of the deeper layers of what is happening and then design our way out of that situation (Stompff et al., 2016). Second, intervening in ongoing situations aims to change the present state of affairs into a different state (Cummings & Worley, 1993) and requires a good understanding of the various social processes that facilitate such transition (Smulders & Bakker, 2012). And starting an inquiry along the lines of Dewey's pragmatism shows a lot of similarities with a K-C-K trajectory from C-K theory. Not surprising, since other authors also saw a close relationship between design and pragmatism (e.g. Dalsgaard, 2014, Rylander et al., 2022).

In other words, intervening the course of action of organizational routines is not really an easy step to make. Even, to initiate a parallel process that aims to investigate the uncanny situation. The problem could be that actors simply don't know how to explore such a situation; there may be a lack of actionable knowledge for a journey in C-space. If they don't have a designer mentality, it is much more comfortable to stick to the current rational state of affairs. And if this is the case, it is not surprising that interventions by those who draw attention to a weak signal often fail. Actors that are sensitive to these kinds of anomalies might have these insights, observations, or feelings much more often. And most likely, if they've tried to intervene and failed more often, they will be known for being too sensitive: ‘Ah, there is Peet again with his outside-the-box observations/ideas/thoughts’. Result is that for their own psychological safety, for preserving personal relationships, these sharp observers will keep silence and over time this could turn into a self-reinforcing norm (Perlow & Repenning, 2009).

Again, the question becomes how to escape from this loophole? Why is it so difficult to engage people in C-space thinking and interacting? Why do we adhere so forcefully to our comfort-zones in the K-space? Is that we miss out on actionable knowledge to be a contributing participant in the C-space or in the inquiry activity?

Suggestion: simple idea, hard to implement

Dear reader, you have read 5000 words to get to the same situation we started from, sorry about that! I worked in a design school for over 25 years and slowly came to understand what design is, and also what design solutions are. One thing became very apparent to me: design solutions are elegant, simple and obvious … at least in hindsight. From the literature on design, there is one stream that particularly resonates with me: the literature on co-evolving problems and solutions. It came to my mind that activities aimed at understanding the problem situation are similar or close to a Deweyan form of sensemaking. It also came to mind that such sensemaking activity is paralleled by a future framing activity at the same time. Meaning, for every step in sensemaking there is an associated (mental) activity in framing future (downstream) activities aimed at resolution, sort of permanent reflective practice (Schön, 1983). These activities meander within the two spaces until they collapse onto each other and become one. A bit like how Einstein has formulated his search for a solution around a tough problem, to spent 90% of the time on the problem, but then designerly different. And you would probably think: Yes, OK, and now what?

I've been struggling with this issue for many years, even decades. Be it in different forms and investigating different manifestations of the same problem, at least that is what I came to realize. A 3-decade long Deweyan inquiry with many dives into various streams of literature and large arrays of experiments. Not only by me, of course, but also under my supervision by MSc-graduation projects and PhD trajectories, all together, more than 150 projects.

Finally, I came to understand the root of the problem we have been discussing here for over 5000 words. Simply said: the problem was the scientific revolution! This revolution initiated in middle of the 15th century brought about a ‘slow’ societal movement that had no precedent: the move of the whole of (western) society from C-space to K-space! This six-century long revolution pushed out the unknown, pushed out the ambiguity, pushed out the many gods we had for all unexplained occurrences in nature, etc. It brought us wealth (of nations), technologies and the industrial revolution. It brought us, rationality, empirical proof, scientific methods, falsifications, rigorous educational systems and above all it brought is ‘decidability’! Decidability for everything, for any object of thought, for any course of action. Everything needs to have logical status. And, during these 6 centuries of moving slowly but steadily to a position far in the K-space we started evenly slow to lose our ability to feel comfortable in the C-space, to be knowledgeable of acting in the C-space. We lost our ability to have a healthy, non-threatening discourse with each other in the C-space, and across the C & K spaces, as depicted in Figure 1. We have turned our (western) society into a society of Flatlanders that only knows two dimensions: false or true.

If this is where we are now as a Western society, then the idea is simple: bring back thinking and interaction in the C-space, bring back transitional and transformational thinking and interacting within the CK-spaces. Let education not destroy this human quality, but rather strengthen it. And certainly, in addition to the technical rationality that is now too dominant. Ken Robinson, the late educational revolutionary, advocated for bringing creativity back into the educational curricula. This was based on his observation that schools seem to kill inherent creativity of young kids and which vision he brought in a famous TED talk in 2006 (Robinson, 2006). The most watched TEDtalk of all times (>80 milj views). He talked about the education of individual kids. Ken may not have realized that by killing creativity on an individual level and raising our children with false/true answers, we as a society also lost the ability to interact with each other in the unknown, in the C-space. We lost our ability to have mixed ambidextrous discourses, K-C-K discourses. We can't switch anymore because we don't know where to switch to. Therefore, any option to switch feels like an unsafe step that will push us out of our comfort zone. We adhere to our ‘validated’ knowledge, that provides decidability, security, and foothold. But as kids, before school and before we were taught false/true knowledge we only had C-space interactions among our friends. That was called play! And we loved it.

And over the past century we see multiple developments in that direction. We mention pragmatism, lateral thinking and game theory as underlying factors for deep change. Game theory as a counterpart to planned change seems better equipped to facilitate change in organizations with socially safe interactions (Boonstra, 2023). Underlying this, one can recognize pragmatism. Fundamentally, pragmatism brings, among other things, a design dialogue that links the domain of theoretical and reflective thinking to the domain of reflective action. In this way, pramatism can be seen as a design epistemology (Melles, 2008; Stompff et al., 2022). If we link this to C-K theory, we can imagine that the ‘playful’ design of a new practice-relevant theoretical framework as a concept (C-space) will form the basis of new organizational routines (K-space). Along the way, we can use concepts such as lateral thinking and PMI tools. These force us to let go of our predefined solutions from the K-space and to look for new perspectives in the C-space.

However, there may be a relatively simple action that we can incorporate into everyday practice. Within the field of design education, the aim is also to prevent students from getting stuck too quickly on the first good idea. This is called design fixation. To increase students' solution space, we ask them to come up with three conceptual ideas, each of which has its own rationality. So not a variant of one of the others, but a solution that starts from a different rationality and/or different interpretation of the situation given to them. That forces students to move beyond the first good and logical-sounding idea into a larger C-space. This can also work in practice. Find three alternatives together that have a logical explanation for the uncanny feelings. Or find three different ideas to get out of the tight situation. Both angles can work. And to really give socio-interactive behavior a good swing in the right behavioral direction, it is wise to subject these three concepts in a joint setting to the PMI process, mentioned above (De Bono, 1982). First look for the Positive elements of a concept, then the elements that require improvement (Minus) and finally the elements that are Interesting. During the P-step, actors come to view something they may not like through positively colored glasses. This frees them from the knee-jerk reflex to get rid of something that does not fit well into their existing logical space (K-space). Doing this could really help to turn the C-K battlefield into a psychological safe design space.

In essence, all creativity procedures are to facilitate C-space interactions. And, then 20 years ago C-K theory was born, maybe after an incubation period of 6–7 years (1996 onwards?), Armand Hatchuel, Benoit Weil and Pascal le Masson brought C-K theory to life in academia and within industry. Later I discovered the deeper layers of CK, its philosophy and its roots and brought that to life for myself and most of all, for my (BSc, MSc & PhD) students, my colleagues, and my clients. A powerful insight. Again later, and just a couple of years ago, I realized that the root cause of all this is our societal shift as initiated by the scientific revolution and to end up in the now with an over-attention to rationality at the expense of room for designerly ‘foolishness’ (Smulders, 2021).

Okay, simple solution: encourage and facilitate the growth of children's natural creativity, while at the same time teaching them to understand the knowledge of K-space along the lines of logic. Teach them the discourses and social dynamics within the two spaces, the transitions, and transformations. Educate them to become ambidextrous grownups. And do the same with grown-ups, governments, political parties, scientists, lawyers, economists, engineers, etc. Education is now too dominantly focused on K-space and STEM subjects. Reading, writing and mathematics, please, add education that focuses on how we deal with each other in uncertain situations, hence, the social-interactive dimension of being human.

It sounds ‘simple come bonjour’, but that is only the sound of it. Operational processes in our society, just like in organizations, also seem to have parasympathetic and autonomous qualities, and can hardly escape from their daily routines. It is very difficult to pause our social ‘belly’ and its processes and collaboratively start an investigation; collaboratively initiate a co-evolutionary (design) process away from current rationalities and look for invisible deeper rationalities, root causes. It cannot be that we, as a mature society, must wait for whistle-blowers to loudly raise the issue of an anomaly that has then grown into a drama. That sometimes works, but is usually disastrous for the whistle-blower, who is often ‘puked out’ afterwards. This conceptual article therefore ends with creativity statement: in what ways can we ensure that social interactions in the unknown (C-space) take place in psychologically safe environments?

Biography

Frido Smulders, is professor Entrepreneurial Engineering by Design at the School of Industrial Design Engineering and the Delft Centre for Entrepreneurship, Delft University of Technology. Frido holds a PhD in innovation sciences from Delft, as well as BSc and MSc degrees in Aerospace Engineering, also from Delft. His career in business prior to rejoining academia spans from concept engineer in offshore industry, materials specialist in aerospace industry and innovation management consultant across the full width of the industry. The latter is what he still does in addition to his work related to the university. He would like to thank Patrick Colemont for his involvement in earlier thoughts on this topic.