“Good Design is Good Business”: An Empirical Conceptualization of Design Management Using the Balanced Score Card

Abstract

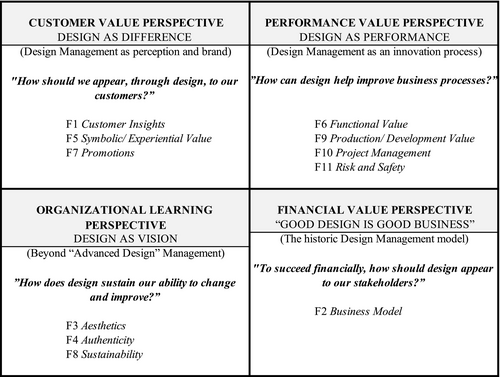

Despite the increasing attention Design Management has received from academics and practitioners a definitive conceptualization or a widely-agreed upon empirical measure of the construct does not yet exist. This paper proposes a new measurement of Design Management based on the informational elements captured in product design briefs. Exploratory Factor Analysis results suggest that Design Management is made up of eleven clusters: F1 Customer Insights; F2 Business Model; F3 Aesthetics; F4 Authenticity; F5 Symbolic/Experiential Value; F6 Functional Value; F7 Promotions/Distribution; F8 Sustainability; F9 Production/Development; F10 Project Management; F11 Risk/Safety. Our analysis describes how these factors show differing effects on measures of firm performance at the product project- and competitive advantage-levels (for example, F1, F3, and F9 are strongly and significantly positively related to both sets of measures while F4, F5, and F8 are more important to the competitive advantage of a firm than to any individual product offering). Our findings are organized and discussed using the Balanced Score Card for Design Management tool made up of (1) Customer Perspective (Design as differentiator); (2) Process perspective (Design as coordinator); (3) Learning and Innovation perspective (Design as transformer); and (4) Financial perspective (Design as good business).

Introduction and background

The insight that “Good design is good business” attributed to IBM President Tom Watson in a talk at Harvard Business School (from Hertenstein et al., 2005) has spurred increasing academic and practitioner attention towards the ways organizations can employ design as a “managed process” within firms (Bruce and Bessant, 2002, p. 38). Increasing scholarly interest has been directed toward helping organizations develop and manage the right processes, resources, capabilities, activities, skills, priorities, and corporate structures that lead to “good design” in their offerings. Indeed, the focus within organizational strategy is now not if good design is good business, but rather how good businesses can get good design (Erichsen & Christensen, 2013; Lardoni et al., 2016). Design Management has been defined as, “…the organizational and managerial practices and skills that allow a company to attain good, effective design” (Chiva & Alegre, 2007). Usage of the term has evolved and changed over time in its meaning, influence, and context, perhaps similarly to the ongoing shift in appreciation of the general concept of “design” (Erichsen & Christensen, 2013, p. 107). Whereas early conceptualizations of Design Management were narrowly focused on helping firms specifically manage “industrial design” as, “the effective deployment by line managers of the design resources available to an organization in the pursuance of its corporate objectives” (Gorb, 1990, p. 68) more recent authors, such as Erichsen and Christensen (2013), use Design Management to make the case for including design within the core strategic functions of a firm alongside the more traditional areas of marketing, finance, strategic planning, technology management, and operational activities.

However, academic findings in the area are mainly qualitative, theoretical, conceptual (Alegre et al., 2008). As Verganti (2006) acknowledges, “We miss a theory to explain why and how leading firms that have brought design at the heart of their business model, such as Alessi, Artemide, Apple, or Bang & Olufsen… The strong focus of recent literature on user-centered design has left a major empty spot in theory of product innovation management: we miss the capability to understand how breakthrough innovations driven by design are created” (p. 5). There are very few empirical studies on the topic to support theory development and encourage the use of Design Management as a variable of organizational strategy research. This means that despite broad and increasing use of the term a commonly agreed upon way to measure and assess Design Management and its components does not yet exist. Indeed, Chiva and Alegre (2007) introduce their use of the manager self-report measurement scale offered by Dickson et al. (1995) by noting that, “…as it appears to be the only proposal to serve this purpose (p. 76). Our study addresses this gap by proposing a new empirical measure for Design Management based on content analysis and expert ratings of product design brief documents as knowledge-based artifacts of firm efforts to manage design within their product develop processes.

The following sections describe our research process involving data collection of product design brief documents and content analysis of the specific information elements contained within these strategically important documents. We propose that product design briefs provide unique insight into the wide variety of processes, activities, skills, priorities, structures, goals, resources, and capabilities that make up an organization’s efforts to manage “good design”. In a second step of analysis we employed Exploratory Factor Analysis to condense these information elements into a grouping of eleven component clusters that represents the important themes of firm’s product design processes: F1 Customer Insights; F2 Business Model; F3 Aesthetics; F4 Authenticity; F5 Symbolic/Experiential Value; F6 Functional Value; F7 Promotions/Distribution; F8- Sustainability; F9 Production/Development; F10 Project Management; F11 Risk/Safety. These factors and their underlying information elements represent among the first attempts to empirically define the specific organizational components of Design Management. Lastly, to rationalize our factors and connect our findings to prior literature we organize our results within the widely-cited Balanced Score Card for Design Management model (Borja de Mozota, 2006). This tool integrates the value-based perceptive of the Balanced Score Card with the Four Orders of Design (Borja de Mozota, 2002, 2006) and provides a useful framework for considering the application of Design Management to firm strategy. Lastly, we extend the framework by using hierarchical linear regression to test the relationships between the eleven factors resulting from our EFA and two forms of competitive advantage identified by Borja de Mozota (2006, p. 46); Design as a Differentiator in individual Product-level Success and Design as Coordinator or Integrator of firm Competitive Advantage. Thereby, our results may help managers evaluate the ways their organizations employ the Balanced Score Card for Design Management by considering the underlying components of the concept in regards to their individual industry environments, competitive positioning, and business goals.

Methodology

The focus of our analysis is a sample of 68 product design briefs we collected from 22 firms representing 17 NAICS industry codes (e.g., Footwear Manufacturing, Hand Tool Manufacturing, Dental Equipment, Motorcycle, Bicycle and Parts Manufacturing, Institutional Furniture, and Kitchen Utensil, Pot and Pan Manufacturing). Product design briefs are documents that capture and codify the many communications, requirements, information and knowledge that pass through a New Product Development (NPD) project. More specifically, a design brief is where various functions engaged in NPD within a firm including marketing, operations/production management, financial analysts, designers, etc. set the objectives, descriptions of the target customers and competitors, product pricing, along with a wide variety of product attribute details-- e.g. shapes and colors, branding, materials, as well as holistic design attributes such as personality and meaning (Borja de Mozota, 2006). Product design briefs have been widely referred to anecdotally in business strategy scholarship (e.g., Bart & Pujari, 2007; Phillips, 2004) and design literatures (Maciver & O’Driscoll, 2010). Following this literature, we contend that these documents are useful artifacts to assess how firms effectively manage people, projects, and processes to design their offerings (Erichsen & Christensen, 2013).

The first stage of our analysis involved conducting interviews with managers and surveying related literature to generate an initial listing of product design brief contents, conceptualized as “information elements”-- e.g., words, text, phrases, concepts, ideas, figures (Paas et al., 2003). In a second step, these information elements were refined through an expert rating process to confirm the initial listing against actual product design briefs created and used by firms in our sample. Expert raters read through randomized product design briefs and graded elements such as “Workmanship” that were deemed to be regularly occurring information elements (mean = 1.21) and were carried through for further analysis while “Customization” was infrequently identified by raters (mean = 0.025) and was therefore dropped. Through this process our listing of information elements was reduced from 138 to a more parsimonious 51. Thirdly, to further reduce our informational element data to a more manageable scope we employed Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) as a standard data-reduction technique to describe groupings of information elements. The EFA process resulted in 11 factors emerging from the 61 information elements: F1-- Customer Insights; F2-- Business Model; F3-- Aesthetics; F4-- Authenticity; F5-- Symbolic/Experiential Value; F6-- Functional Value; F7-- Promotions/Distribution; F8-- Sustainability; F9-- Production/Development; F10-- Project Management; F11-- Risk/Safety. These factors account for 79.31% of the variance (K-M-O statistic, 0.879; Bartlett statistic, 6554.11; significance = 0.000). These factors and their contents are discussed below (Table 1).

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer insights | Business model | Aesthetics | Authenticity | Symbolic/experiential | |

| Percent of variance | 36.8 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 3.7 |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.90 |

| Expertise | 0.70 | ||||

| Consumer involvement | 0.68 | ||||

| Product-user interactivity | 0.68 | ||||

| Consumer segments | 0.61 | ||||

| Comparisons | 0.54 | ||||

| Originality | 0.53 | ||||

| Firm-level positioning | 0.52 | ||||

| Innovativeness | 0.52 | ||||

| Differentiation | 0.51 | ||||

| User health | 0.44 | ||||

| Price point | 0.80 | ||||

| Sale prices | 0.79 | ||||

| Earlier products, brand | 0.57 | ||||

| Forecasts | 0.55 | ||||

| New market intro | 0.52 | ||||

| Prod-level positioning | 0.46 | ||||

| Styling | 0.67 | ||||

| Multiple versions | 0.66 | ||||

| Graphics | 0.64 | ||||

| Aesthetics | 0.62 | ||||

| Associative | 0.61 | ||||

| Materials | 0.54 | ||||

| Design language | 0.43 | ||||

| Workmanship | 0.39 | ||||

| Authenticity | 0.55 | ||||

| Consumer meaning | 0.42 | ||||

| Prestige | 0.75 | ||||

| Status | 0.71 | ||||

| Emotional appeal | 0.58 | ||||

| Touch | 0.51 | ||||

| Comfort | 0.51 | ||||

| Sensory appeal | 0.50 |

| F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | F11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional value | Promotions | Sustainability | Production/dev | Project management | Risk/safety | |

| Percent of variance | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| Product performance | 0.70 | |||||

| Technical specifications | 0.67 | |||||

| Weight | 0.64 | |||||

| Product quality | 0.52 | |||||

| Ergonomics | 0.47 | |||||

| Technology | 0.45 | |||||

| Product life cycle | 0.61 | |||||

| Related promos | 0.55 | |||||

| Tagline | 0.54 | |||||

| Distribution/suppliers | 0.48 | |||||

| Sustainability – production methods | 0.72 | |||||

| Sustainability – design process | 0.67 | |||||

| Production facility | 0.63 | |||||

| Production capabilities | 0.48 | |||||

| Target dates | 0.63 | |||||

| Project goals | 0.60 | |||||

| Sizes | 0.37 | |||||

| Product risk | 0.72 | |||||

| Product safety | 0.61 |

Discussion of results

To help rationalize our discussion of these factors we will employ the Balanced Score Card (BSC) perspective of Design Management created by Borja de Mozota in her widely-cited article Four Powers of Design: A Value Model in Design Management (2006). The BSC (Kaplan & Norton, 1996) is a foundational business concept developed to help firms build strategies based on alignment between four inter-related concepts: Customer Value Perspectives, Financial Value Perspectives, Internal Business Processes, and Innovation and Learning metrics. Borja de Mozota (2006) extend this idea by applying the BSC concept to Design Management to provide design professionals within organizations with a tool to measure, manage, and defend their contribution to firm value by using language and concepts familiar to business managers. Borja de Mozota (2006) contends that this model is useful for supporting the role of design in firm strategy because it represents the value created by designers in, “… the language shared and understood by most executives” (p. 47). Specifically, the BSC for Design Management tool integrates the Four Powers of Design (from Borja de Mozota, 2002): Customer Perspective (Design as differentiator); Process perspective (Design as coordinator); Learning and Innovation perspective (Design as transformer); and Financial perspective (Design as good business). Accordingly, the following sections discusses our empirical results through the Balanced Score Card for Design Management model as discussed below (Figure 1).

A second focus of this study is to extend the Balanced Score Card for Design Management model (Borja de Mozota, 2006) by testing the relationships between the factors of Design Management we identified in our EFA on outcome measures of firm performance. Following the suggestion of Borja de Mozota (2006) we considered firm performance at two levels: To assess Design as a differentiator we measured the project-level performance of individual firm offerings offered by Design Management by adapting extant measures of new product success related to sales, return on investment and market share (Atuahene-Gima et al., 2005) secondly, to evaluate Design as Coordinator or Integrator we measured the overall firm-level competitive advantage produced by Design Management (Swink & Song, 2007).

Our analysis of the association between the 11 factors identified in our EFA process and our two performance measures was based on hierarchical linear regression to test the relationships under consideration (i.e., the direct path between each factor and both levels of performance). Computed reliabilities for our dependent variables were: Product-level Performance, 12-items (α = 0.72) and Competitive Advantage, 6-items (α = 0.80) (Table 2). Our results suggest that the overall effect of our construct on both Product Success (F-value = 17.688, p-value < 0.001) as well as Competitive Advantage (F-value = 24.841, p-value < 0.001) is strong and positively statistically significant. Although, perhaps most interestingly our findings also imply that individual components of DM may have differing effects on these measures. Specifically, while the factors of F1 Customer Insights, F3 Aesthetics, and F9 Production/Development appear strongly related to both levels of firm performance, our data also suggests that F4 Authenticity, F5 Symbolic/Experiential Value, and F8 Sustainability are more important to enduring Competitive Advantage than any single product offering. While alternatively, F6 – Functional Value, F7 Promotions/Distribution, and F11 Risk/Safety were most strongly associated with the successes of individual product projects. The following sections discusses some of the highlights of this analysis and relative related literature and the relationships to our two measures of firm performance.

| Balanced score card for design management | DV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Product success | R 2 | F-Ratio | Competitive advantage | R 2 | F-Ratio | |

| CUSTOMER VALUE PERSPECTIVE | F1 – Customer insights | 0.052*** | 0.062 | 10.957 | 0.135 | 0.106 | 17.797 |

| Design as difference | F5 – Symbolic/experiential value | 0.236** | 0.056 | 8.829 | 0.293 | 0.086 | 14.109 |

| F7 – Promotions | 0.302*** | 0.091 | 15.065 | 0.342*** | 0.117 | 19.862 | |

| PERFORMANCE VALUE PERSPECTIVE | F6 – Functional value | 0.325*** | 0.105 | 17.688 | 0.377*** | 0.142 | 24.841 |

| Design as performance | F9 – Production/development | 0.201 | 0.04 | 6.324 | 0.306*** | 0.094 | 15.55 |

| F10 – Project management | 0.228** | 0.052 | 8.228 | 0.314*** | 0.099 | 16.401 | |

| F11 – Risk and safety | 0.311*** | 0.097 | 16.109 | 0.358*** | 0.128 | 22.075 | |

| FINANCIAL VALUE PERSPECTIVE | |||||||

| “Good design as good business” | F2 – Business model | 0.052 | 0.019 | 2.849 | 0.151* | 0.037 | 5.705 |

| ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING PERSPECTIVE | F3 – Aesthetics | 0.285*** | 0.081 | 13.231 | 0.291*** | 0.084 | 13.827 |

| Design as vision | F4 – Authenticity | 0.169* | 0.029 | 4.42 | 0.254*** | 0.065 | 10.347 |

| F8 – Sustainability | 0.2 | 0.04 | 6.274 | 0.439*** | 0.193 | 35.909 | |

- *** p < 0.001

- ** p < 0.01

- * p < 0.05.

Firstly, within CUSTOMER VALUE PERSPECTIVE our results provide clear empirical support for the notion that a focus on understanding customers and their needs is essential to how organizations effectively manage people, projects, and processes to design their offerings (Erichsen & Christensen, 2013). Caban-Piaskowska (2016) suggest that consumers desire inimitable things that are specially-designed; these can be everyday items, but they have to look differently, be designed for particular types of interiors and be unique. The supports the characterization of Borja de Mozota (2002) of Design as Difference. Successful Design Management seems to be clearly related to firms’ abilities to focus and direct their product design processes to deliver these important strategic attributes and create differentiation from competitor offerings. As Acklin (2013) suggests; customers and their problems are in the center of interests of companies that apply Design Management. Within our empirical results, Factor 1 Customer Insights, Factor 5 Symbolic Experiential Value, and Factor 7 Promotions appear related to this perspective. (see Figure 1). F1 Customer Insights contains underlying information elements of Design Management seem related to research such as McCormack, Cagan and Vogel (2005) who suggest that customer-centric inputs have a critical importance to successful NPD processes. Rothwell and Gardiner (1989) argue that one of the most important aspects of Design Management is a thorough understanding of the company and its competitors. In particular, these authors suggest that high-functioning firms rely upon information accurately defining their target customers (e.g., our information elements “Customer segments”) as well as how those consumers perceive and evaluate offerings in the marketplace (e.g., “Innovation”, “Originality”, “Comparisons”, and “Differentiation”) and how they will consume or use the offering (e.g., “User expertise”, “Consumer involvement”, and “Consumer interactivity”). Our regression results suggest strong positive support for the powerful product- and firm-level effects of clear Customer Insights (F-value = 10.957, p-value < 0.001 for Product Success and F-value = 17.797, p-value < 0.001 for Competitive Advantage). Our findings align with many descriptions of Design Management as a “managed process” within firms (Bruce and Bessant, 2002) to direct and focus information gathered about target customers into distinctive offerings that will stand out from rivals and connect with target customers. As Best (2006) argues, “Apart from quality and functionality, design management enables an organisation to fulfil the needs of consumers who expect high aesthetic experiences, i.e. added value in products addressed to them” (p. 6).

Secondly, F5 Symbolic/Experiential Value (e.g. “Prestige”, “Status”, “Luxury”, “Comfort”, “Sensory Appeal” information elements) aligns with findings in NPD and business strategy literature that suggests that contemporary consumers have come to expect product functionality and quality as prerequisites and that truly successful products must not only perform well but also resonate with consumers in some emotional way (Hertenstein et al., 2005). McBride (2007) connects Design Management to this drive toward distinctive product offerings through the creation of “non-material value” (p. 17), which causes consumers to evaluate not only on their physical or technical attributes but to see, “…nearly all things as experience goods” (p. 22). Our results confirm that F5 Symbolic/Experiential Value is more important for holistic firm Competitive Advantage (F-value = 14.109, p-value < 0.001), rather than individual product performance (F-value = 8.829, p-value < 0.01). This may be because consumers are able to gain more emotional and symbolic meaning through brand attributes which tend to endure and carry through multiple individual product lines. As an example, Borja de Mozota (2006) describes in a case study the important impact brand value has on the success of the Decathlon TriBord Surfing Wetsuit and how Design Management contributes to the maintenance of this connection consumers perceive in the Decathlon brand embedded across their 65 sports categories (p. 50). The significance to the customer seems to be clearly related to the “Status”, “Emotional appeal”, and “Prestige” they feel towards the broader Decathlon brand. Accordingly, our results support the notion that an important Design Management function is to manage the value of brands across many different product lines (Crilly et al., 2004). It also implies that the concept of Design Management is inherently a dynamic concept that requires firms, designers, and product managers adapt and evolve their conceptions of “Status”, “Prestige”, and “Sensory appeal” over time. As Muenjohn et al. (2013) contend, firms must take into account that consumers continuously expect “modern design”, which means that successful offerings depend upon Design Management acclimating to the visual and artistic evolution of their consumers.

Third, the PERFORMANCE VALUE PERSPECTIVE of the Balanced Score Card for Design Management captures a organizational capabilities-oriented view of Design as Performance (Borja de Mozota, 2002), where our F6 Functional Value, F9 Production, F10 Development, and F11 Risk/Safety capture the multitude of firm process for managing design within NPD including “Deadlines”, “Timelines”, “Product performance”, “Technical specifications”, “Quality management”, “Technology”, “Development”, and “Project goals” as well as how this critical information flows between different functional areas of the organization. Many depictions of Design Management emphasize that an important characteristic of firms that effectively use design is their ability to successfully structure and manage cross-functional product development teams (Martin, 2009). Miller and Moultrie (2013) argue that one of the key benefits of Design Management is the synergy it fosters within interdisciplinary project teams. Indeed, McBride (2007, p. 20) argues that, “Design management is a method of supporting the development of networking and building relations through a greater awareness of the need for connections between the worlds of producers, technologists, constructors, as well as artists and designers, with the community of recipients and consumers of art and design.” Our results provide clear empirical support for these benefits, showing significant positive relationships between F6 Functional Value for both Product success (F-value = 17.688, p-value < 0.001) and Competitive Advantage (F-value = 24.841, p-value < 0.001) and F10 Development Processes at the Product- (F-value = 8.228, p-value < 0.01) and Competitive Advantage- (F-value = 16.401, p-value < 0.001) levels. These findings provide much needed support for the notion that effective Design Management has concrete effects on individual product projects as well as the overall competitive advantages of the firm. While authors (Rothwell & Gardiner, 1989) have advocated for the importance of design departments to be considered equally with marketing, sales, engineering or research departments the lack of clear empirical findings may have impeded both the broader acceptance of design as a strategic function within firms and what specific tasks Design Management supports within NPD.

Lastly, our F2 Business Model appears to be the only factor related to the FINANCIAL VALUE PERSPECTIVE of the Balanced Score Card for Design Management (Borja de Mozota, 2006). These underlying information elements capture the tactical aspects of NPD such as “Product price point”, “Forecasts”, mode of “Market entry”, “Product-level positioning”, and the firm’s “Previously introduced products”. Our results show a non-significant relationship between F2 and Product success (F-value = 2.849, p-value = 0.052) and a weakly significant effect on Competitive Advantage (F-value = 5.705, p-value < 0.05). Our interpretation of these results is that while this factor of Design Management would appear intuitively to be very important to both product- and firm-level performance anecdotal discussions with managers suggest that its influence may have already been decided upon before being catalogued in a Product Design Brief. For example, one respondent in our study described how a Product Design Brief for a microwave oven within their firm may contain information elements related to F2 Business Model that specify the outward appearance, pricing strategy, and product-level positioning of the product (e.g, aluminum, with rounded corners, a rubberized handle and a white digital touchpad, at the $XX price point). However, they note that this design information was already widely understood across the organization and any individual product would be expected to align with the broader brand positioning of the firm (i.e., as a modern and expensive offering relative to competitors). In addition, as suggested in Borja de Mozoat (2006) within the Steelcase case study, Design Management may have many outcomes that would be poorly represented in measures of Product performance or Competitive Advantage. Specifically, the case notes that, “Measurements related to the workplace have typically focused on cost per workspace, space efficiency, reconfiguration costs, and energy use—the cost side of the cost/benefit equation. The workplace, however, significantly affects an organization’s people, processes, and technology. In the business results model shown below, the workplace is one of four key factors that drive business results. Efforts in all four areas must be integrated, balanced, and measured” (p. 52). This suggests that many of the benefits of Design Management such as reductions to the Time and costs for workplace moves, Facilitating more fluid team-based work processes, and Lower operational costs may not show up in our measures and that the overall effects of Design Management should be assessed holistically across all four areas of the Balanced Score Card for Design Management.

Conclusions

A significant contribution of this study is to highlight the separate, yet essentially connected relationships among technical, production, marketing, and Design Management functions within NPD. For example, F1 Customer Insights contains several elements of traditional marketing-related information, including descriptions of “Consumer segments” and “Firm-level positioning”, however the factor also contains information elements related to engineering/production functions of a firm (i.e., “Innovativeness” and “Product-User interactivity”) as well as design-related “User health” and “Originality”. These results can be taken as evidence for the broad diversity of information and knowledge necessary for successful Design Management.

This study also presents an empirical conceptualization of the various subcategories and relationships between components of Design Management—in particular our results may provide a much needed clarity to the actual functions of design as a “managed process” (Erichsen & Christensen, 2013) where concepts that were historically lumped together may be more effectively considered separately. For example, F3 Aesthetics includes information elements related to an offering’s “Graphics” and “Materials”, while F6 Functional Value contains “Ergonomic” and “Performance”, and F4 Authenticity captures “Consumer meaning”. This suggests that Design Management within contemporary organizations may include far greater variety of contributions to a successful product than late-stage product packaging.

Third, by organizing our empirical results within the Balanced Score Card for Design Management (Borja de Mozota, 2006) we address how Verganti (2006), among others, have argued that most firms do not develop a strategic vision for the use of design as a source of long-term competitive advantage. Borja de Mozota (2006) specifically developed the framework to, “…bridge the gap between the world of designers and the world of managers” (p. 44). Our findings highlight how Design Management functions to translate various forms of firm design knowledge into “Good Business”. Lorenz (1995) argues that, “…to present, nobody has been able to develop a clear way of characterizing design in an organization” (p. 74). This historic shortcoming may, in part, explain why the treatment of design and Design Management more specifically has been less developed than other aspects of NPD (Gemser & Leenders, 2001).

Finally, this study has implications for practitioners. Organizational managers involved in managing design within their firms may use this study to refine their thinking about investments in design-related capabilities. The structuring of Design Management within the Balanced Score Card model provides a tool managers can use to advocate for design in their organizations as well as a framework for benchmarking the underlying components of Design Management within their firm’s processes, resources, capabilities, activities, skills, priorities, and corporate structures that lead to “good design”.

Biographies

Ian D. Parkman is an Associate Professor of marketing at the Pamplin School of Business at the University of Portland. He teaches undergraduate- and MBA-level classes in Marketing Strategy, Marketing Research, and New Product Design and Development. His research interests focus on marketing strategy, design-driven innovation, the creative industries, and knowledge-based product development. He has published his work with the Journal of Brand Management, the Journal of Design, Business, & Society, dmi: Review, among others. He holds an MBA from the University of New Mexico and his Ph.D. is from the University of Oregon.

Dr Keven Malkewitz is a rare mix of industry experience and academic expertise. A lifelong interest in sports products and product design led him to a fifteen-year career as a manager around the globe for Adidas (1983–1998). Dr Malkewitz’s passion for products and the product development process led him to pursue a second career researching consumer behaviour. He now researches the influence of design in the new product development process. He has published design-related articles in several peer-reviewed journals such as the Journal of Marketing, the Journal of Retailing and the Journal of Business Research. His background in product development and management allows him to provide a unique perspective on how the development process is influenced by design-related issues and by knowledge management. He earned his undergraduate degree from Hope College in Holland, Michigan (double-major in business and English) and his Ph.D. in marketing (consumer behaviour emphasis) from the University of Oregon.