Design Management Staircase as a Measuring Unit: Understanding Design in Cairo Startups

[Article updated on 25 November, 2021 after first online publication: Table 3 has been corrected.]

Abstract

Although there is a great need for Design, limited research is conducted on Design Management (DM) in the Middle East compared to Europe. One development in Cairo in the past decade is the increase of startups, generating a diversity of offerings. It is believed that the higher a company is on the DM Staircase, the more revenue it gets, among other benefits. Since Cairo startups are aiming to raise the Egyptian economy, this paper aims to define where Design lies by using the staircase as a measuring unit to plot startups against. Narrative interviews were conducted and processed to gain understanding from entrepreneurs and identify common terminologies used by startups. This paper addresses whether DM is adopted in Cairo but under different terminologies. It was found that existing Design terminology is frequently used in English which is not yet translated to Arabic, leading to miscommunication. Moreover, the paper concludes the plotting of startups against the DM Staircase to classify their Design integration. It was found that the level of DM involvement for the startups interviewed was at the lowest two levels. Therefore, this plotting paves the way for business consultants to help elevate startups onto the DM Staircase.

Cairo entrepreneurship scene: overview of the status quo

Egypt has witnessed several developments over the past decades in terms of economic growth and expansion, one of which is the increase in the rate of startup launching and incubators that support entrepreneurship. This is due to the economic shifts that occurred after the 25th of January revolution in 2011 as well as the heightened empowerment of Egyptian youth. Consequently, many young entrepreneurs decided to embark upon business opportunities to serve Egypt’s growing market needs. These entrepreneurs often create startups in around ten sectors including education, IT, and retail (Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, 2019, p. 38). The GEM argues that policy changes and entrepreneurial education can urge more people in Egypt to embrace opportunities. This serves as a solution for Egyptian's not exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities as Egypt only holds 2% of adults remaining Established Business Owners. This might mean that Egyptians, along with other countries such as Puerto Rico, Mexico and Oman, are struggling to transform a starting business to an established organization (Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, 2019, p. 14). Despite Egyptians noticing potential in startup opportunities and claiming they have enough skills, Egyptians are pulled back by their fear of failure (Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, 2019, p. 31). While the Egyptian entrepreneurial scene continues to grow in diverse fields, an opportunity presents itself to closely study Cairo entrepreneurs’ understanding of Design and consequently predicting their potential in the future.

Lost in translation: design translation challenges

‘To have a second language is to have a second soul’, stated Charlemagne, a holy Roman emperor. Cognitive Scientist, Lera Boroditsky, adds that 7000 languages are spoken around the world, each with unique sounds and structures. This suggests that language can strongly affect the way people think and interpret information differently. For example, in Spanish one would say ‘The vase is broken’, while in English one would say ‘He broke the vase’. Consequently, Spanish speakers neither care nor remember who acted, unlike English speakers, therefore affecting the way people place blame or simply interact in daily activities (Boroditsky, 2017). Similarly, in the Design world, Mozota and Wolff discuss Latin American countries facing the challenge of translating Design Management (DM) terms which in Spanish are translated into ‘Management of Design’, leading to miscommunication. Those translation problems create misunderstandings between Managers and Designers which can cause a rejection of the concept of Design Management (Mozota & Wolff, 2019). This means that Design terms cannot simply be translated by anyone; more research is needed to accurately make sense of these terms in different languages. Sadly, Erin McKean, an English language lexicographer argues that creativity is encouraged in all fields except languages. She adds that people follow grammar and vocabulary rules whether consciously or unconsciously. People are urged to make up new words to keep languages alive through several revival techniques (McKeen, 2014). It is, therefore, unfortunate that Design is yet to encourage people to invent new words when such Design-based lexicography can be an exciting research area.

Likewise, the same issue is visible in Cairo; Egyptians do not speak Classical Arabic but rather speak modern standard Arabic. Classical Arabic is used mainly in education and formal documents, and even the modern standard Arabic differs from one Arabic speaking country to another. Due to invasions throughout the years, several words were adopted from other languages like French, German and Turkish while others were invented by Cairo’s youth. Schools in Cairo teach Arabic as the first language along with a second language which is most commonly English. Due to globalization and international influences such as media, movies, and television series, the English language is integrated into everyday conversations between certain segments. Consequently, several terms either do not exist in Arabic because they were not studied and developed or because it’s easier to use the term in another language. To bridge the gap, this study also aims to document terms used in Arabic by entrepreneurs that describe Design, whether intentionally or unintentionally. It is aimed that, eventually, similar documentation would lead to English-Arabic Design lexicography. A crucial aspect of analyzing one's awareness of a topic is to document the actual phrasing and terms used to describe it. In this case, the links between interviewees’ level of awareness as well as the most commonly used terms to describe Design and DM were documented.

Aim of the study

‘When all businesses are designing value-added, user-oriented, desirable products it will be those with good design management practices that will be able to stay ahead’ stated Darragh Murphy (Kootstra, 2009, p. 4). Over the past decade, research has proven the value of integrating DM into companies’ frameworks. Several researchers have emphasized the importance of DM inclusion early in a company's foundation (Best et al., 2010). Organizations that invest and include Design within their management become fast-growing, profitable, and innovative (Kootstra, 2009). Although DM offers several benefits to organizations, it also has its challenges. Mozota and Wolff explain three main challenges to DM: lack of communication between educational facilities of both disciplines, lack of interest from Management of Design, and vice versa. Although Cairo is currently witnessing an increased development in entrepreneurship offering innovative solutions to market needs, an understanding of Design and how it can benefit companies is still missing, especially to those starting up. Best, Koostra & Murphy found that ‘Most European small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) lack sufficient grasp of the role of design and that their focus on its management is still underdeveloped’ (Best et al., 2010). Likewise, this paper targets young entrepreneurs in Cairo and aims to understand startups in Cairo and their relationship with Design.

Several methods of plotting and measuring have been developed including the Design Management (DM) Staircase by Koostra to involve the plotting of a company’s level in terms of specific factors. Previous researches implementing this method use quantitative methods such as surveys to gather data from companies and plot accordingly. However, these methods lack the in-depth knowledge and interpretations that qualitative methods offer. Therefore, the study aims at using narrative interviews to extract information from local startups in Cairo. The information was analyzed, coded, and plotted against the DM Staircase. The research also included an in-depth analysis of terminologies used by the entrepreneurs to describe Design within the company. While Cairo has a growing percentage of market-driven startups there are yet to be any studies that focus on the entrepreneur's Design awareness. The study hypothesizes that the level of Design understanding and awareness of Cairo based startups will be at the lower two levels on the staircase. The research aims to find out the plotting location as well as the possible reasoning behind a startup’s placement. The use of the staircase will also help compare the startups to each other, thus analyzing the difference between startups on higher and lower steps.

Theoretical framework

Defining design management

Design Management is a field of study with different understandings and explanations. According to Borja De Mozota and Wolff, DM lies between Design and Management disciplines (Mozota & Wolff, 2019) where it merges both fields (Johansson & Woodilla, 2008). DM is also said to be the Management of Design which involves the integration of Design within the Management process of an organization (Best et al., 2010). It manages the crucial skills, activities, and procedures necessary to fulfil complex Design processes within companies (Kootstra, 2009). To integrate Design within the Management of companies, new skills need to be added or developed including the skill to ‘manage designers’ inside a corporation (Johansson & Woodilla, 2008). By doing so, business performance will be increased which would, in turn, create employment opportunities that focus on services to increase DM inside companies (Best et al., 2010). Therefore, the role of Design managers within companies is found to enhance their overall performance (Kwoon et al., 2007).

The value of design inclusion in organizations

Mckinsey’s 2018 Business Value of Design report illustrates a company’s market share increases of 40% due to its novel user-centric products that were distinguishable among competitors (Sheppard et al., 2018). Organizations that apply DM developed innovations by remaining advanced in the market and offering solutions to current customer needs. The opposite was found concerning companies with little focus on innovation; DM is not included in their organization. Therefore, both DM and innovation management are fundamental (Best et al., 2010). In 2014, the Design Management Institute set out to focus on defining the value of Design and realized that Design benefits in successful Design-led companies are difficult to identify because of how integral it is within the overall culture of the company and is, therefore, not a separately identifiable department. The study, inspired by the work of Sabine Junginger at the Danish Design Council, was able to extract a three-part framework to measure Design value. The DMI Design Value project, therefore, uses three main elements; Design as a tactical driver, Design as an organizational driver, and Design as a strategic driver (Westcott et al., 2013).

Professor Kotler, a management educator, defines Design as a strong yet unused tool for businesses, which includes components such as performance, quality, durability, appearance, and cost. He adds that Design helps maximize revenues through consumer satisfaction. Designers view and are viewed as hard to manage and unpredictable whereas managers are viewed as uninformed in the business’ visual elements and only care about profits (Clipson, 1984). In 1992, Clipson suggested that inefficient Design professions are due to the lack of University doctoral programs in Design studies, causing gaps between Design education, research, and practice (Clipson, 1992). While Design graduates are skilled in their Design fields and professions, they lack the training to enable them to launch their own business or work inside a starting organization. Although tasks in an established company are defined, those required inside a startup are not as clear which means designers need to be trained to communicate and exchange knowledge in interdisciplinary situations. Because of this uncertainty of startup’s tasks, as well as the lack of needed training, Design entrepreneurs find it difficult to launch and manage a business (Valencia Hernandez & Pearce, 2019).

Although Design inclusion involves several values there are also challenges in adopting Design within an organization, one of which is the added cost required. To solve this, a change in perception and awareness is recommended to achieve the recognition that Design is an investment for the company’s future. This can be achieved by measuring the added benefits of Design inclusion to prove and communicate to managers and decision-makers the importance of investing in Design for the company’s future (Westcott et al., 2013). Therefore, it was deduced that Design’s involvement in a company, especially when implemented while launching a startup, has several benefits including distinguishable products in the market, high customer satisfaction, and an increase in revenue. It was also found that a greater emphasis on involving Design into the launch of startups can greatly affect their success rate in terms of profit, advancement in the market, and staying ahead to ensure the startup’s survival.

Methods of measuring design inclusion

To create awareness and convince company owners of DM’s values it is important to visually plot its benefits throughout the years. Measuring methods can be used by consultants to plot a company’s current status to convince managers of proposed solutions and approaches. A study developed by the Design Management Institute (DMI), found that Design is ‘under-employed and under-valued’ creating a lack of ‘conscious, systematic, or strategic’ Design inclusion within companies. Companies, therefore, focus only on its added cost and not on the returned added value (Best et al., 2010, p. 34). Another measuring method is the DMI Design Value Index, developed in 2014 by the consulting firm, Motiv Strategies. It offers value tracking of companies known for integrating DM to identify Design and innovation impacts on a company’s stock value over some time (Westcott et al., 2013).

In 2001, the Danish Design Centre developed the Design Ladder to measure and communicate Design’s inclusion in companies (Figure 1). It hypothesizes that the more Design is integrated strategically the more profit occurs. It encourages Design inclusion early in a company’s development stage and its general business strategy (Danish Design Centre, 2015). According to Figure 1, the ladder consists of four steps that gradually increase from lowest to highest Design inclusion: Non-Design where the company does not focus on the user’s perspective, Design as form-giving involves focusing on the final product, Design as a process integrated early in the company’s development process with professionals involvement, and Design as a strategy where designers and company owners develop a process based on the business’ role in its future value chain.

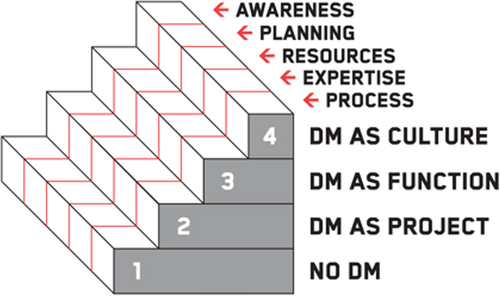

The development of the design management staircase

The DM Staircase was developed to visualize a company’s behaviour and involves four main levels (stairs), similar to those of the Design Ladder (Figure 2), gradually increasing from lowest to highest. It suggests that the higher the staircase level the greater the strategic Design importance within a company (Best et al., 2010). Level 1 describes No DM with little to no involvement of Design procedures with few rules or guidelines. Level 2 companies are those that include Design for a business requirement, for example, to increase their product lines or develop existing portfolios. In this case, it is used as a finishing tool and not included to develop innovation. Level 3 includes companies that assign the task of managing the Design process to a department or employee. They represent a link between the designers and the rest of the company. The fourth level involves companies that aim towards becoming market leaders by developing their innovation through Design. They, therefore, adopt DM as a culture within the company and develop their point of difference around strategies based on Design and innovation. Level 4 companies are those that are starting up, with a focus on innovation and/or Design (Best et al., 2010). Each level of the staircase is further broken up horizontally into five factors which act as indicators towards good DM practice. These factors include Awareness of Design Benefits, Process of DM, Planning and strategy of Design in the company, Expertise including the quality of staff and tools used, and finally the Resources the company uses to involve Design in the organization (Kootstra, 2009).

The use of visual plotting systems would, therefore, help deliver messages to business owners about different Design inclusion levels and its potential for success in those areas. The staircase offers an in-depth overview of a company's position across several functioning elements inside an organization. This measuring method can be conducted, plotted, and compared to get an overview of companies’ different positions.

Empirical research

Methodology overview

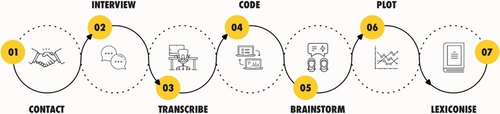

This study uses the DM Staircase to measure the Awareness levels of different startups based in Cairo. Although previous plotting attempts have been conducted they used quantitative methods such as questionnaires to gather and plot statistics. However, quantitative methods do not guarantee the participants’ knowledge which could affect the findings’ accuracy. Furthermore, a research opportunity was presented as no literature investigated startups using a qualitative method. Therefore, this study uses narrative semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions to extract information from Egyptian entrepreneurs. This method was selected to avoid guiding the sample into answering specific answers and to encourage them to open up about their startups through stories. Figure 3 illustrates the process followed throughout the entire study where interviewees were contacted to schedule a meeting. Interviews were conducted, recorded using a mobile phone, translated from Arabic to English, and transcribed manually using Microsoft Word. The documents were imported to Atlas.ti where open coding was managed across all interviews, followed by selective coding. Afterwards, brainstorming sessions took place to revise all codes and code groups, where the axial codes emerged. Code groups were mapped and considered to plot the startups onto the DM Staircase. Finally, interviews’ recordings were revised to detect Design related terminologies (Figure 3).

Sampling and interviewing

The study followed a sampling criteria based on inclusion and exclusion. Over two weeks, 10 interviews were conducted with startup founders or the person aware of the startup’s procedures and resources. Inclusion sampling was based on ages, ranging from 25 to 40 years old and startup size, ranging from 3 to 17 employees. Figure 4 shows the startups interviewed; the current number of employees, years in the market until the time of the interview, type of target market, sector, and interview medium. Out of the interviewees, 3 were females and 7 were males, with a range of 1–7 years in the market, as shown in Table 1. The startups ranged in 7 different sectors with 3 startups targeting both businesses and customers: 4 target customers, and 3 target businesses. All interviewees have different university degrees including Software Engineering, Business, and Fine Arts. On the other hand, entrepreneurs with no university degrees were excluded, along with non-Egyptian entrepreneurs, and entrepreneurs living outside Cairo, aged under 25 or older than 40 years. In addition, any startup having more than 20 employees or operating for more than 10 years in the market were also excluded. Therefore, the quality of diversity in this group provides this research with a wide spectrum of insights.

| Startup code | Employees | Years in market | Types of market | Sector | Interview medium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 8 | 7 | B2B-B2C | Education | One to one |

| 02 | 4 | 5 | B2B | Real estate | One to one |

| 03 | 8 | 2 | B2C | Food & beverage | One to one |

| 04 | 15 | 1 | B2B | Data science | One to one |

| 05 | 5 | 6 | B2C | Education | One to one |

| 06 | 16 | 2 | B2B-B2C | Education | Phone call |

| 07 | 3 | 6 | B2C | Furniture | Phone call |

| 08 | 17 | 4 | B2B | Medical | Phone call |

| 09 | 5 | 1.5 | B2C-B2B | Laundry | Phone call |

| 10 | 3 | 2 | B2C-B2B | Furniture | Phone call |

Before the interviews, a general research objective was communicated to the interviewees: to understand how their startup operates and their plans in the future. It was intended not to communicate the specific study topic to avoid guiding the interviewees to certain answers. In the beginning, respondents were given the freedom to use their terms about Design which was then used throughout the entire interview. Most interviews were around 20–60 minutes long depending on the interviewee’s Design awareness and practice. Control questions were either asked at the start or end of an interview to validate the sampling criteria. Questions were open-ended and differed from one interview to another. Generally, entrepreneurs were asked to tell the story of the startup, what type of market they serve, how many employees they have, and how long they have been operating. They were asked if employees in the company are full-time or part-time and if they outsourced any parts of the business operations. The interview then moved into their definition of ‘Design’ and where it plays a role in their business. They were asked about previous experiences with Designers and how it affected their startup, positively or negatively. They were asked how they imagine Design’s role in the company’s future and, finally, if they previously heard about DM.

Research findings

Findings phase I: code groups

The Codes, as shown in Table 2, were bundled under 6 Code Groups: Design Definitions, Design Benefits, Design Drawbacks, Design Management, Boosters, and Non-Design Challenges. Some Codes were labelled under more than one Code group (Table 2).

| Code group | Amount | Most used codes | Findings & insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Design definitions | 16 codes | Aesthetics, communication, perception, visualization, social media, logo, marketing |

|

| 2. Design benefits | 18 codes | Aesthetics, visuals, design for growth |

|

| 3. Design drawback | 10 codes | Skills needed, designer fees, time consumption |

|

| 4. Design management | 5 codes | Design for growth, design value, DM awareness, DM process, DM resources |

|

| 5. Boosters | 11 codes | Inspiration, outsourcing |

|

| 6. Non-design challenges | 5 codes | Cost, funding, prioritizing, startup sustainability |

|

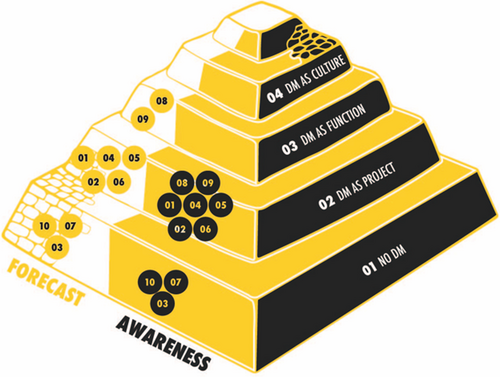

Findings phase II: plotting against DM staircase

After revising the Codes, startups were plotted onto the DM Staircase. For the study’s scope, only the DM Awareness column was studied since the entrepreneurs lacked knowledge about the other factors. Figure 4 presents a redesign of the DM Staircase which contains DM Awareness and DM Forecast Adoption.

As hypothesized, all 10 startups plotted in the lower two levels: 3 on the first level with no DM integration and 7 on the second level of DM as a Project. In the Awareness column, the startups on Level 01 indicated no or minimal DM adoption due to limited Design knowledge and lack of Design Value understanding. Startups placed here due to them emphasizing that Design is not integral and perceived as an aesthetic tool. These 3 entrepreneurs mentioned the least Design Benefits as compared to the rest. Remaining startups lie on the second step (DM as a Project) as they currently utilize Design as a tool for styling and visualization. While they adopt Design continuously and perceive its impact, they do not hold a full-time Design Department. Design, to them, is used regularly but not daily. Although all 7 were located on the same step some plotted slightly higher in terms of their Awareness than others.

As the plotting process took place, it was found that although some companies currently plot in Levels 01 and 02, their responses indicate DM adoption potential and increased DM adoption in the future. Therefore, the Forecast column illustrates startups 01, 02, 04, 05, and 06 on the second layer as they intend to increase their Design use as they grow. They seem to be aware of several Design disciplines despite only using a few. Their plotting position was due to their openness to expand their current Design adoption from hit-and-run into a project-based culture. Moreover, 08 and 09 lie on the third step where Design acts as a functional in-house (or outsourced) department. These two entrepreneurs, in particular, seemed to have the most understanding of Design and DM. They expressed a thorough understanding of a Design Manager’s role tailored to their industry. They also imagined a structured department that plans and evaluates Design processes and resources to maximize efficiency.

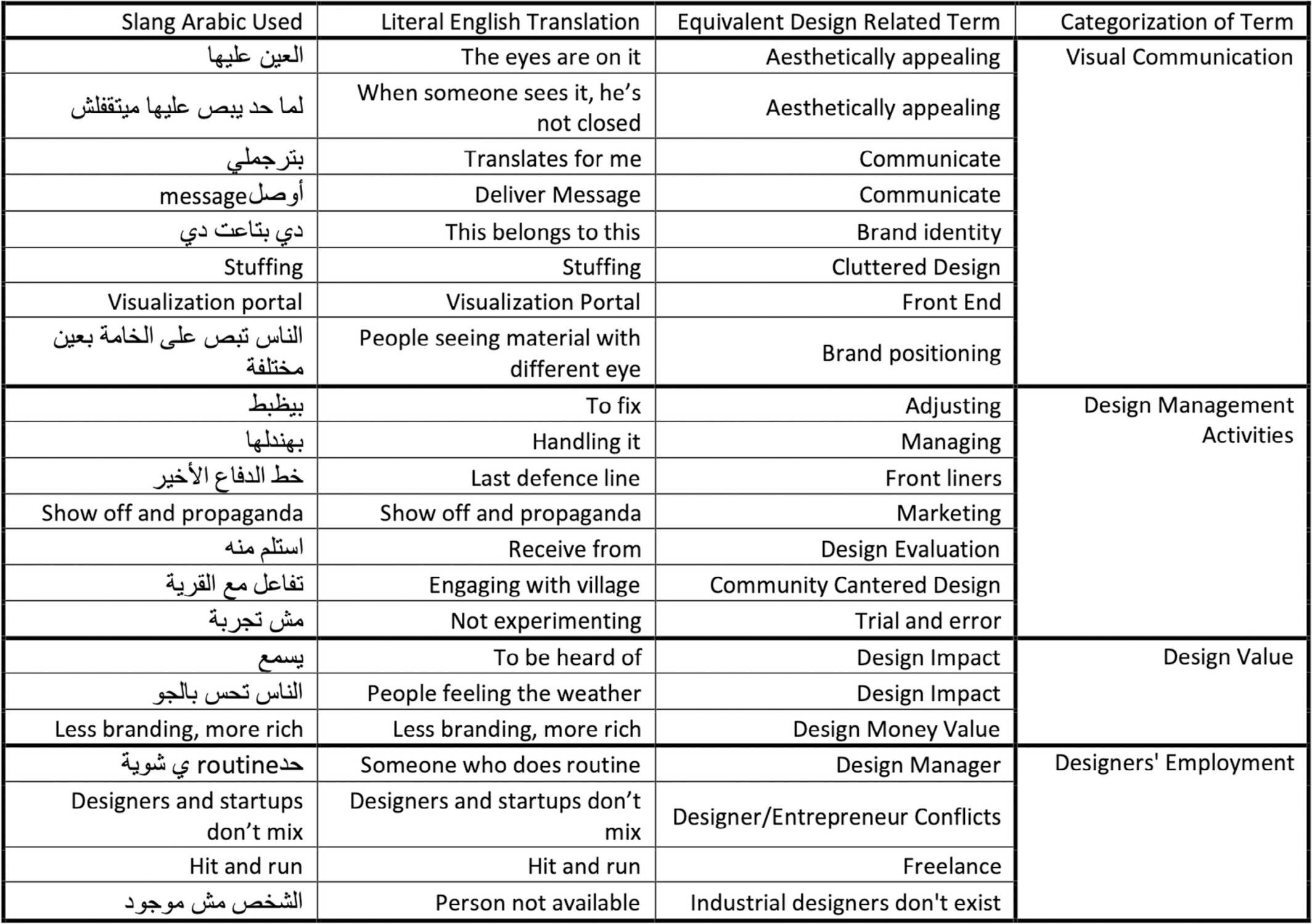

Findings phase III: terminology extracted

To further understand the entrepreneurs’ Design perception, another layer of the study involved listening to the interview recordings and extracting terminologies commonly used by the entrepreneurs. The terms were analyzed, translated, and categorized into five main clusters: Visual Communication, DM Activities, Design Value, and Designer’s Employment. Table 3 indicates extracted quotes from the interviews which were either Arabic, English, or a mixture of both. Literal English translations were made and what was meant by the quote was described in the ‘Equivalent Design Related Term’ column. Some commonly used terms were in English as there are yet to be Arabic words that describe the same intended meaning.

Entrepreneurs describe positive Visual Communication differently; each gave the term his/her interpretation. These selected terms are among many that prove that most entrepreneurs perceive Design as an aesthetic form-giver. On the other hand, despite all stating that they do not know what DM is, they have revealed certain DM activities (Table 3). This confirms that their common sense helped them arrive at such conclusions. In a future study, these expressions can be further explained to help them unlock the potential of DM. The Design Value terms seem quite shallow and intangible, for instance, the term “يسمع” which translates to “to be heard of” was mentioned several times to resemble the way they imagine a Design’s impact. Furthermore, all entrepreneurs find difficulty in communicating with designers; several struggles were mentioned yet designers' employment proved to cause the most problems. For example, one of the entrepreneurs stated: “Designers and startups don’t mix”. These extracted terms correlate with the “Skills needed” Code which played the biggest role in the Design Drawbacks Code Group and, thus, proving the gap between Designers and Entrepreneurs. Finally, Entrepreneurs struggle to express themselves, as evident in Table 3, where slang Arabic terms are relatively longer in word count (60 words) than Design expressions (40 words).

Reflection

From DM staircase plotting: entrepreneurs mind-set

The study indicated a direct correlation between entrepreneurs’ mindsets and their level of Design awareness. Entrepreneurs exposed to more versatile experiences, with an active tendency to read and self-learn in different fields, plotted higher in awareness. Plotting related to entrepreneurs’ previous work involvements, information sources about Design, startup’s sector, and perceived Design requirements. For instance, one entrepreneur was professionally involved with a Branding Designer so Design was related to branding. Another entrepreneur owns a furniture brand where Design understanding was limited to products and aesthetics. The entrepreneur in the food and tourism industry described Design as marketing to attract customers and promote their food. This indicated general stereotyping towards the role of the Designer; Design is involved in the aesthetics and visualization of the brand but not used in any of the management decisions of the company. Several entrepreneurs also showed a lack of open-mindedness which affected their plotting levels. For example, one entrepreneur mentioned their dislike towards Designers who promote themselves as a sign of ‘showing off’. Only two entrepreneurs were aware of the different fields and types of Design adoption for the growth of their business, thus increasing their potential for Design adoption.

The research provided a starting point for future studies to plot the level of Design awareness in other businesses as well as more established, larger companies. Although the method of qualitative research was successful in extracting vital insights, the plotting method of the staircase was confining and designed mainly for methods of a quantitative nature. Therefore, for future development, another plotting and visualizing method could be developed to communicate company status to responsible people within organizations. DM awareness can be provided as a service to inform companies about its benefits and potential usage. A gap in Designers' employment possibilities in Cairo with specific roles related to DM consultancy was indicated. Moreover, startups are encouraged to develop attractive packages to induce designers’ commitment.

To extract more insights and knowledge, further development into how the study is conducted is also recommended. This can be done by providing startups with a workshop or previous knowledge before starting the interviews. Different types of qualitative research methods can also be conducted with different focal points; startup history, entrepreneurs’ backgrounds including personal and professional experiences as well as education. It is also recommended to cluster further interviews into units, for example, based on the entrepreneurs’ study disciplines or business sectors. The above suggestions support this research through qualitative and quantitative forms, providing a clearer picture of Cairo startup patterns.

From terminologies: design lexicon initiative

Terminologies extracted provided an overview of an entrepreneur’s knowledge about Design and proved that, in some cases, Arabic words are substituted by English if they are not available or commonly used. Interviewees’ educational backgrounds and exposure affected how frequently they used English in their answers. However, English terms used during the interview could also be due to the language’s usage by the interviewers while asking the questions. For further development, this should be taken into consideration to enhance the study.

A relationship between the terminologies used by the entrepreneurs and their Awareness levels was indicated. One study limitation is the lack of previously conducted research in a similar direction to refer to. This gap acted as an enabler to indicate possible approaches for future research including an in-depth etymology study of the origin of words for the development of a Design and Management dictionary. Also, as Design adoption is going viral from one continent to another, the need for this Design specific dictionary grows to avoid potential misunderstandings. To achieve a useful modernized Design lexicon, it is recommended that a multidisciplinary team is recruited to conduct the required research since co-creation is crucial for the lexicon to meet both Design and business sectors.

Future impact: education and practical implications

While entrepreneurs need to expand their thinking horizons to accept Designer and Design, Designers also need to acquire more diverse skills to be a better fit for startups. The biggest limitation of this study is the lack of information specific to Egypt in terms of research methods, continuous measuring of Design adoption, and educating entrepreneurs about Design. Evidently more research is required in this area. In addition it is recommended for future research to limit the choice of interviewees by sector or entrepreneur’s background in order to create a different comparison. Plotting startups against the DM Staircase regularly or creating an Egyptian DM Staircase that fits local startups’ can guide entrepreneurs to plan and act for the future. It can also act as a starting point for consulting agencies when assisting struggling startups. While consultants and entrepreneurs play a crucial role in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, educational facilities must respond to communicating Design value before the undergraduate level, where both Design and Management fields are taught providing a general understanding of both disciplines before graduation. These conclusions, therefore, are the beginning of a series of projects, research papers and collaborations to better bridge the gap between designers and entrepreneurs.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Prof. Dr Brigitte Wolf, Miroslaw Leczeck and Gwendolyn Kulick for their generous feedback.