Creative Leadership: Design Meets Neuroscience to Transform Leadership

Abstract

Creative Leadership (CL) is a tripartite leadership model that has been developed and pioneered by Rama Gheerawo, Director of The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design at London’s Royal College of Art. It evolved over the last decade through observation and experience of the limitations of hierarchical models of leadership across a diverse range of sectors. During this time, the three Creative Leadership attributes of empathy, clarity, and creativity have been explored through a range of primary and secondary research methods. The next stage of research and development involves a multidisciplinary convergence of design thinking with neuroscience that relates to brain plasticity, neural connectivity, and emotional intelligence theory. The aim is to develop a comprehensive grid of key performance indicators of CL. Dr. Melanie Flory, neuroscience project partner, explains that the three attributes are learnable and correlate positively with well-being-sustaining values and behaviors in individuals and groups. When the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of these traits are identified and understood, a three-dimensional complementary feedback loop of learn–retain–apply can ensue through experiential learning and development. This positioning paper presents the evolution, scope, and applications of CL alongside a discussion of the emerging opportunities for novel design–neuroscience intersection relating to personal, leadership, and organizational development, growth, and transformation. It also reflects on the pandemic context of 2020.

1 Introduction

Creative Leadership is not a leadership strategy. It is a transformational process in which individuals tap into their innate creativity, and the potential to lead themselves and others towards fulfilling the goals and vision of the organisation or project.

1.1 A changing landscape of leadership

The leadership landscape is changing. Whether a small-to-medium enterprise, a large industrial company, or an academic department, leadership increasingly requires a more creative position (Amabile and Khaire, 2008). Creatives are used to being constantly challenged and working within a moving, morphing remit, which makes them adept at adapting to forms of leadership that are more dynamic than static, and incorporating multiple perspectives rather than being single-pointed or one-dimensional. The competitive world of business, however, rarely recognizes this, preferring to maintain the status quo of outdated and outmoded forms of leadership that are top-down, process-driven, and inflexible, and which do not typically account for people (Gheerawo, 2018).

Creativity is important, and the economic value of the creative industry sector in the UK steadily increased between 2010 and 2016 at nearly twice the rate of the entire UK economy during that time (Cotton, 2018). In 2016, its economic value stood at £100bn. In November 2018, through a government press release (HMSO, 2018), Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) Jeremy Wright, speaking about the phenomenal economic growth in UK creative industries since 2016, announced: “Today they [sic] have broken the £100bn mark.” In 2019, the UK creative industries economic value stood at £286bn, with Wright pledging, “Our creative industries not only fly the flag for the best of British creativity at home and abroad but they are also at the heart of our economy.” This signals creativity as a new currency for the economy, with powerful potential for applications within leadership.

To date, the term creative leadership has largely denoted leadership strategy for the creative sector, or engagement with an artistic mindset in management. In this research project, which has inclusivity at its heart, it has been defined as a transformational process that delineates characteristics that can be applied to individuals, groups, organizations, technologies, and projects. Although it draws on practice from the creative industries, it transcends disciplines, roles, and institutions. This paper presents the current status and recent developments of this research inquiry, ensuing from an unfolding collaboration between design and neuroscience researchers.

In parallel, empathic leadership emerges as a reflective, quieter, and more collaborative position, and it is being seen as important in the changing world of leadership theory and practice. This is also noticeable within design practice as a growing ambition over the last two decades and has been endorsed by McGinley (2012), who maintains that an empathic stance is essential for designers developing their own practice. Linking an organization’s direction to the personal individual perspectives and aspirations of its employees can help align ambitions and engender a more focused and vibrant workforce.

1.2 Leadership in a crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to the fore a primary modus operandi of conservative, hierarchical leadership by governments across the globe. This is a leadership approach that, in itself, is set apart from any political affiliation. “This is how you do it” and “this is why you do it,” reinforced by imperative statement hashtags, are the order of the day.

In crisis management where fast-acting, immediate mitigation measures are vital to saving human life and preventing the escalation of a problem and its effects, this line of action can indeed provide the guidance and level of direction needed amid times of uncertainty, limited clarity, and systemic instability. However, this style of leadership could be considered dictatorship if not fueled by underlying empathic approaches to understanding the complexity of the problems at hand and ensuing solutions. The National Health Service (NHS) and government ascribe to empathy being an essential first step to developing clarity regarding the way forward (Howick, 2019).

In the wake of an almost global lockdown informed by scientific evidence prognosticating the escalation of loss of human life before any reprieve, we see a secondary model of leadership emerging behind the scenes that is strongly aligned with creativity and creative thinking. This emergence is driven by the need to bring about immediate day-to-day operative and strategic solutions that directly relate to improving personal experience and the need to be a part of the solution to save lives. An example of this in the UK was clearly displayed when medical staff, with their backs up against the wall, balanced patient care duties and the inner call to save lives with the need for self-preservation and personal safety. TV channels reported how frontline staff took to using bin bags, home-laundered protective clothing, and face masks in an attempt to be safe and get on with the business of serving the nation’s sick through the machinery of the NHS.

These, and similar activities, are examples of leadership initiatives and qualities that emerge from within the individual, provoked by a felt user need that focuses and drives energy toward the emergence of clarity and the blossoming of new insights and pathways to solution finding and innovation-based thinking. Creative Leadership (CL), with its tripartite unison of empathy (EMP), clarity (CLA), and creativity (CRE), is clearly a model that falls within the second category. This way of leading from within, irrespective of status, is highly participatory and contributory, thereby enriching the whole.

In the current global crisis, this is borne out every day as journalists tell stories of individuals, organizations, and communities immersing themselves in team-spirited creative thinking and efforts to ease, console, alleviate, solve, transform, and influence, in some small way, the pain and fear generated by the reality of the threat to human life. This empathy-based participation is not lost in time and space—not for the individual or the collective. It is an empathy with purpose. In its own wake it leads to creative objectivity on different levels. From banding together to explore and formulate new hypotheses to being a part of a local food provision volunteer group, each participant requires little incentive to be a part of the solution while acting safely.

COVID-19 has shown us that leadership styles must evolve. Science and art must collaborate and complement each other. The authors believe that CL is not just about leadership, but a solution to the huge job of people-centered design and innovation that is here to stay. If ever there is a new normal, design, creativity, and innovation are at the center of it. Every day, this reality is showing up for the sole trader and the multibillion-dollar corporation.

2 Driven by Design

The program of CL research grew from Inclusive Design (ID) practice at The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design (HHCD), which was defined by the UK Department of Trade and Industry (2000) as “products, services and environments that include the needs of the widest number of consumers,” marking it as a creative strategy for business, and linking social equality to innovation. ID has been described in various ways—as a practice, methodology, philosophy, or technique—but a key effect is that it is internationally recognized and used by governments, industry, designers, policy makers, and social and creative organizations. The idea was articulated by Coleman (1994) at the International Ergonomics Association’s 12th Triennial Congress and now forms the underlying focus at HHCD, which Gheerawo now directs. Over 300 ID projects have been conducted with around 200 organizations, forming an evidence base for empathic and creative practice.

ID shares its ideology with Universal Design (UD) and Design for All (DfA). All three have their origins in designing for older or disabled people, but they have evolved to embrace varying uses, definitions, and applications. As Vavik and Gheerawo (2009) note, different cultural, historical, and political factors across the world have affected the precise way in which these ideals have been interpreted and expressed.

People-centeredness and empathy are widely accepted components of design approaches, as noted by several researchers and practitioners such as Beverland, Wilner and Micheli (2015), Liedtka, Salzman, and Azer(2017), and Newton and Riggs (2016). Gothelf (2017) describes the need for an empathic look at users or consumers, and Curedale (2015) notes that the field of design has evolved to become less about making people want things and more about answering human need.

Creative Leadership started with a single insight—that we need more creatives in leadership positions and that the world would benefit from leaders who are more creative. This led to an inquiry into the specific qualities designers could bring to leadership; the value of their creative capacity in navigating complexity, ambiguity, and uncertainty; and the opportunities for design tools and processes, particularly those of human-centered and collaborative approaches, to develop leadership capacities in individuals and organizations (Figure 1).

The concept was born in 2007 while Gheerawo was delivering ID projects and workshops in Trondheim, Norway. Although the concept was not defined until later, he recalls that this was the point in time when CL began to form as a domain in its own right, quite separate from ID and Design Thinking, with the latter described by Brown (2008:86) as “a discipline that uses the designer’s sensibility and methods to match people’s needs with what is technologically feasible and what a viable business strategy can convert into customer value and market opportunity.” CL, on the other hand, was conceived by Gheerawo as a framework to enable designers to step into leadership positions, and a more creative stance for leadership as a whole.

These ideas grew from Gheerawo’s experience in personally leading over 100 design projects with government, business, and the third sector—from small and medium enterprises to large multinationals—where the three values of EMP, CLA, and CRE began to emerge as essential to developing products, services, and systems that aimed at improving people’s lives. Two examples of such projects are presented below. Although specific components of the three values were prominent in each project, the authors’ evolving CL practice highlights that they all need to be present throughout an entire project to ensure meaningful outcomes with a full and vibrant effect.

2.1 Redesigning the London taxi

“The Future London Taxi” project was a collaboration between HHCD, the Intelligent Mobility Design Centre at the Royal College of Art (RCA), and Turkish vehicle maker Karsan. Empathy—at a number of different levels—was important in informing the project brief and drawing together the different political, creative, and engineering entities involved. The project brought in service users with a range of mobility issues, requiring immersive and empathic techniques to be deployed. An advisory group of experts was created to enable wider advocacy. Central to the process was the use of a rough prototype to enable co-creation with a range of people, which allowed changes to be made in “real time.” Participants remarked on this as positive—their ideas and comments were seen to demonstrably impact the physical design.

An important user group was drivers because for many cab drivers, their vehicle doubles as an office, a place of rest, a workspace, and a canteen. The London Taxi Driver Union was heavily involved in the project, creating a sense of co-ownership of the creative process. The drivers themselves defended the design ideas as their own in public fora that occurred at London City Hall. Driver well-being was seen as important, and an overriding sense of empathy informed the research and creative outputs. The result was the organic development and delivery of inclusive design. More than 150 changes were proposed that would make London’s iconic black taxis a more creative, accessible, and luxurious proposition.

2.2 Using AI to support communities with mental health

“Our Future Foyle” is a city-scale, socially transformative project based along six miles of riverfront along the River Foyle in Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland. This three-year project began in 2016 as research commissioned by Public Health Northern Ireland to look at improving the mental well-being of the local population. The river’s estuary separates Northern Ireland from the Republic of Ireland and is still a disputed territory. In this area, suicide rates are the highest in the UK, and the swift-running River Foyle has drawn many troubled people to its bridges. HHCD worked with the community to deliver some transformative interventions to the river area.

“Foyle Reeds” is a public interactive art sculpture that doubles as a suicide prevention barrier. “Foyle Aware” is a media campaign, also designed by HHCD, to improve awareness of mental health and help the community identify people in need of support before a crisis point is reached; and “Foyle Bubbles” are portable spaces along the river bank and bridges occupied by existing organizations and individuals from community, arts, and commercial sectors trained in mental health awareness.

The Future Foyle project aimed to draw in an estimated £15m in European, governmental, and industry funding. At the heart of the project was the need for clarity—an understanding of the social, economic, and community factors that drove the project team. Clear problem definition, clear communication with the community, and enhanced empathy in dealing with a highly sensitive subject were important in building trust at all levels, from the locals in the neighborhoods to the political decision makers. Throughout this project, the practice of CL in the designers’ thinking and behavior helped realize “Our” in the “Our Future Foyle” project.

2.3 The three values of Creative Leadership

The term creative leadership was first used in the 1950s (Selznick, 1957), and since then it has been predominantly associated with a style of leadership that encourages creativity in devising new business strategies and models (Puccio, Mance, and Murdock, 2011; Sohmen, 2015; van Velsor, McCauley, and Ruderman, 2010; Vernooij and Wolfe, 2014), in organizational development and change management (Sternberg, Kaufman, and Pretz, 2003), and in building environments and teams that use creative processes in innovating products and services (Mainemelis, Kark, and Epitropaki, 2015; Mitchell and Reiter-Palmon, 2017; Mumford, Scott, Gaddis, and Strange, 2002; Stoll and Temperley, 2009). In the creative industries, creative leadership is synonymous with visionary thinking and being a pioneer in a respective design or creative field (Berlin School of Creative Leadership, 2017).

In all cases, engagement with creative thinking and mindset is at the core, and in 2010, an IBM study of global CEOs established that business leaders themselves acknowledged creativity as the top leadership quality that would require attention and development (IBM, 2010). In recent years, this has formed the basis for new leadership and innovation programs that teach creative thinking and skills, with a view to “unlocking leadership potential” (CCL, 2018).

Gheerawo’s CL model speaks to a wider need for personal and organizational development, with applications that balance human and technological factors and center on new and enduring values. Gheerawo elaborates that whereas traditional notions of leadership are top-down, hierarchical, and reliant on solid structures and levels of management, his design practice, lived experience, and reflection over the last 20 years indicated a need for a more quiet form of leadership, which centered on people as the living body of an organization, and the driving force behind an undertaking, or project.

The purpose was to develop a program of delivery in areas of personal and organizational development, as well as practical applications in innovation and project management, demonstrating appreciation and knowledge relating to the ever-emerging need and demand for innovative and culture-building leadership through experiential learning and development.

As illustrated above, the model has been shaped and honed over the last 10 years to arrive at a theory, through practice. This led to the formulation of the tripartite model of EMP, CLA, and CRE, based on the following principles: “Everyone has leadership potential; creativity is defined as a universal ability to develop solutions that positively impact ourselves and others; empathy is the hallmark of a 21st-century leader; and clarity is the link that aligns vision, direction, and communication, in a personal undertaking, organisation, or project” (Gheerwo, 2018; Gheerwo, 2019).

The Creative Leadership components of EMP, CLA, and CRE essentially address the need for individuals to adapt and succeed in a VUCA1 environment—notwithstanding the current pandemic—predicted by John Chambers, CEO of CISCO (McKinsey and Company, 2016), who says, “Business models will rise and fall at a tremendous speed. And it will be a brutal disruption, where the majority of companies will not exist in a meaningful way 10 to 15 years from now.”

3 Neuroscience meets Design and Leadership

3.1 Brain plasticity and creative thinking

Why does every generation feel that the world they live in is in continuous flux, and that over the last 50 years alone, that change is occurring with unprecedented rapidity and far-reaching global effect? Could this have anything at all to do with the evolutionary history of the human brain?

The evolutionary sciences tell us that the size of the human brain has fluctuated over the past 3 million years. However, a spurt increase in brain size occurred between 800,000 and 200,000 years ago (George, Marshall, and Webb, 2018), which is about the size of the human brain today. It so happens that this time period is marked by dramatic climate change. The need of the hour for our ancestors was for greater ability and capacity to process new information, make appropriate decisions, and take actions that raised the potential for survival and continuity of self, one’s immediate group, and, by implication, the human race.

This ability of organic material (i.e., cellular matter) to morph and mold in response to the environment within which it exists and operates is called plasticity. The term used to describe this quality in the brain as neuroplasticity (Begley, 2009). What is pertinent to this paper is that brain changes occur on an individual and collective basis as we go through the motions of everyday life.

Following close on the heels of brain evolution is the traceable history of human innovation and design thinking in response to felt and perceived need. The biological response to “come out of the cold” or “make a fire” is borne out by archaeological evidence of cave dwellings in France and Germany, which have been carbon dated to some 400,000 years ago (Pobiner, 2016). Travel forward to 100,000 years ago, and we see hominin shelters decorated with ornaments made of bone and shell. From the hand-hewn dwellings of our ancestors to the cityscapes of today, the environment–brain evolution–innovation–design interrelationship is undeniable.

For as little over a decade now, neuroscience research in organizational change and development has involved brain function studies of real-time leadership scenarios with innovation and creativity tasks, amongt others (Fink et al., 2009; Limb and Braun, 2008; Molenberghs, Prochilo, Steffens, Zacher, and Haslam, 2017). Sporns, Tononi, and Kotter (2005) maintain that leadership studies involving mapping of brain activity—known as connectivity mapping—allow for objective observation, measurement, and interpretation of connectivity and brain plasticity relating to leadership thinking and behaviors.

Creativity, to one degree or another, is a ubiquitous and complex feature of human thought and behavior (Limb and Braun, 2008). Connectivity studies by Limb and Braun (2008) evidence that specific areas of the brain work together during creativity and innovation tasks. In popular parlance, this is called firing (i.e., activating) and wiring (i.e., connecting) together.

Connectivity studies involving creative improvisation tasks (Limb and Braun, 2008), creative problem solving (Fink et al., 2009), and inspirational leadership (Molenberghs et al., 2017) show that specific areas in the brain are activated when participants are given creative or innovation tasks, and that these activations correlate to specific types of cognition such as reflective thinking and decision making. The steadily growing body of neuroscience research evidence posits a strong argument for collaboration between neuroscientists and designers in developing theory, content, and design of education and training materials that enable the firing of specific neural networks associated with generating targeted leadership traits and behaviors. It extends the scope for intersection and co-creation between the two disciplines in areas such as user experience, evidence-based design of learning materials, applications building, cognitive and emotional intelligence training, and inclusion-based factors such as cultural nuance and workplace environment.

3.2 Neuroscience and Creative Leadership

Gheerawo’s CL is constructed on the foundational premise that everyone is a leader, and our whole lives are filled with opportunities for leadership growth. Flory explains that this perspective is especially empowering and timely in confronting the complexities of a pan- and post-COVID-19 world, where uncertainty, coupled with precariousness, gives rise to the desperate need for EMP, CLA, and CRE to address the reality and looming threat of demise, collapse, chaos, and finger-in-dike scenarios.

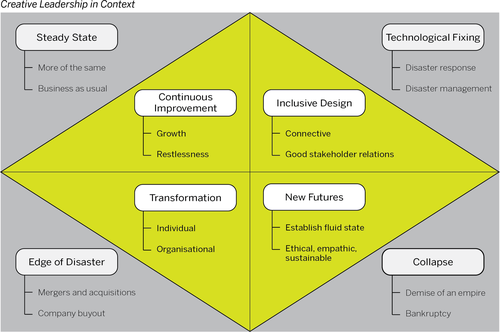

Even during times of comparative stability, biological and social systems are in a continuous state of flux that embodies features of both permanence and change (Bohm, 2002; Wheelwright, 2013). Through Figure 2, Flory illustrates the value of CL in the context of organizational development. She explains that the gray triangles depict organizational responses to ever-changing PESTLE2 factors. The four-part diamond presents the ethos, enablement, and effect mediated by CL on an individual and organizational level.

EMP, CLA, and CRE are sustaining human values in themselves. Several branches of neuroscience are steeped in research inquiry relating to these human traits in order to understand their value and affect not just on one’s own thoughts, behaviors, and feelings, but also on how their expression can lead to better relationships and outcomes for all (Decety and Ickes, 2009). Organizational leadership and development primarily rest on this premise.

3.3 The neuroscience of Empathy, Clarity, and Creativity

CL is first and foremost a practice in empathic response to the need for change, innovation, and transformation. Empathy-led exploration and understanding put people first, and are the “necessary revolution” (Senge et al., 2008) to creating a sustainable world for people and the planet. Because empathy is a felt and observable human trait, it can be continuously developed and refined, and people at every level in the organization can become transformers of the businesses and communities they are a part of.

Research evidence from the emerging field of social neuroscience, which studies brain activity while people interact, is beginning to reveal new verification about what makes a good leader (Goleman and Boyatzis, 2008). These researchers maintain that great leaders are those who understand the importance, value, and need to behave in ways that powerfully leverage human connectedness, both with oneself (intraconnectedness) and the group (interconnectedness)–namely, empathy.

Although a comprehensive discussion of neurobiological and social neuroscience evidence relating to the traits of CL lies outside the scope of this paper, it is pertinent to note that the evidence emerging over the last two decades relating to empathy and the empathy spectrum of emotion and behavior such as sympathy and compassion (Trieu, Foster, Yaseen, Beaubian, and Calati, 2019), using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and self-assessment tasks, has led to rigorous evaluation and evidence that clearly show empathy can be acquired and developed by taking advantage of neuroplasticity. Trieu et al. (2019) maintain that understanding the neurobiological basis of empathy can help inspire clinical staff to improve their intra- and interconnectedness skills and strategies for better patient care and experience. These findings can help inform learning and development of empathy for leaders and designers.

In relation to creativity, a critical review of fMRI studies published from October 2010 to October 2011 carried out by Sawyer (2012) identified distinct brain circuits that correlate with higher-order cognitive processing, that is, different types of creative cognition. Sawyer (2011) concluded that cognitive neuroscience has the potential to contribute a valuable perspective to creativity researchers and teachers. Almost a decade later, Greene, Freed, and Sawyer (2019), who have a continuous and well-respected record of research in this field, are convinced of the advantages of collaboration between cognitive neuroscientists, creativity researchers, and creativity and design educators to help advance understanding and education, and build applications that incite creative thinking and behaviors in schools and the workplace. They stress the importance of teaching and learning how to activate types of creative thinking (e.g., creative insight, hypothesis generation, story generation, story arcing, mind wandering, etc.), and advise: “Continued interdisciplinary collaboration has the potential to further advance our understanding of the mental processes and structures associated with creative thought and behaviour” (Greeneet al., 2019, p. 130).

The subject of mental clarity is vast, and it straddles theory and research across a number of subdomains within neuroscience. These range from the neurobiology of dementia and the autism spectrum disorders to mathematical ability and problem solving in early education.

In this early dawn of collaboration between design and neuroscience, it is proposed that a contained approach to collaborative research and design relating to enablement and actuation of mental clarity be taken. Flory proposes that this can be achieved by exploring and examining the research evidence relating to the theory, learning, and practice of psychological flow, which offers a one-place, evidence-based repository relating to clarity, rather than the herculean task of sifting through the myriad of specialized clinical condition studies (e.g., Alzheimer’s) relating to mental clarity.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the father of flow concept and theory (1975), uses the term flow to describe the optimal human experience of being in a highly focused mental state while fully engaging in an activity—cognitive and/or behavioral. The resultant unique brain state observed in EEG neurofeedback studies (Cheron, 2016; Gruzelier, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c) correlates with specific brain activation; an increase in subjective reporting of happiness and enjoyment; and increased productivity. Most human beings have experienced the flow state at one time or another in activities as varied as organizational scenario planning and writing to jogging and playing football.

Cognitive and behavioral capabilities that correlate with flow state, which can be taught and learned, include fluidity in attention and action, intrinsic motivation, clarity of goals, and aha moments relating to creativity and invention (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). All of these qualifiers are explicitly and implicitly present in Gheerawo’s definition of clarity (see Table 1), and they are borne out by Flory’s observation of workshops executed by Gheerawo and his team at the HHCD.

| Empathy is the ability to recognize, understand, and reflect on the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of others. Simply said, it is the ability to put ourselves in the “shoes” of another and understand what their experience might be like. |

| Clarity is having a clear understanding of the vision and direction of the organization or project. It is the ability to effectively communicate this to a variety of audiences. To be clear is to maintain an accountability mindset that supports the growth of the individual, team, and organization. |

| Creativity is the ability of an individual or a group to utilize their intellect, skills, and resources to create solutions, services, and products that are novel, useful, and relevant. |

Flory has already begun the groundwork for developing a multilevel model of CL, which in turn will organically inform a psychometric key performance indicators (KPI) test of CL for individuals and organizations (Cipresso and Immekus, 2017).

4 Research and theory building

Over the last decade, the CL program of research and development has constituted a range of activities, including testing in the field through executive education, interdisciplinary research through the coming together of design and neuroscience researchers; a pilot test; qualitative research through interviews; and delivery of design and innovation projects; all of which have helped to refine and hone the model, grow the evidence base, and identify opportunities for further research and applications development.

4.1 Experiential learning

To date, the CL model has been trialed via delivery of over 50 executive education and bespoke workshops with over 5,000 people across the UK, Norway, Denmark, Poland, Bulgaria, United States, China, and Singapore, among others, and the oversight of more than 250 people-centered projects across private, public, and voluntary sectors of the economy. Although not formalized as research, these workshops have allowed for direct testing of receptivity to the CL concepts across demographics and observation of how the CL principles are expressed in group interactions and creativity tasks, as well as testing and refining design methods and tools that help people understand and practice attributes associated with EMP, CLA, and CRE.

Although the teaching and materials were drawn from design, participant groups have ranged from large multinational corporations to NGOs and startups, civil servants and policy makers, academic institutions, designers, marketeers, and entrepreneurs working within the finance, logistics, technology, pharmaceutical, health, well-being, social, and creative sectors.

Creative Leadership is a “must” for leaders who want to break down barriers and be respectful of the emerging changes being brought about in leadership influenced by those coming into the workplace for the first time, who will not tolerate the top down approach of yesteryear. (Workshop participant, November 2019)

Participants report feeling engaged, responsive and inspired, as well as finding personal resonance with the concepts and their applicability. Post-workshop, participants have shared how the workshops have affected their personal life and transformed their professional outlook, which fulfills a primary intent of CL, which is to enable people “to tap into their inner selves, their inner voice, their inner knowledge, giving them permission to be their creative self” (Oral history interview with Gheerawo, Ivanova, 2018).

4.2 Interdisciplinary-led research inquiry

- What is the neuroscience evidence base proposing and affirming about organizational leadership, in general; and human cognition, emotion, and behavior relating to clarity, creativity, and empathy, in particular?

- What kind of education and training would help activate these traits on an individual and collective level, and ensure long-term memory retention and practice of these traits?

- What are the design methods and processes that can achieve the objective outlined in (2) above?

4.2.1 Intersection of neuroscience and design in practice

In addressing these questions, a multilevel (cognitive, affective, and behavioral) approach to identify, categorizes, and order the correlates of thought, emotion, and activities relating to CLA, EMP, and CRE is a first-level approach that will give access to formulation of key performance indicators that are identifiable and measurable. The corollary of this is that new learning and development methods, materials, and applications informed by this evidence base can be designed so as to educate and train individuals and groups in being change-ready, intelligently adaptable, responsive, and to be leaders in change and innovation.

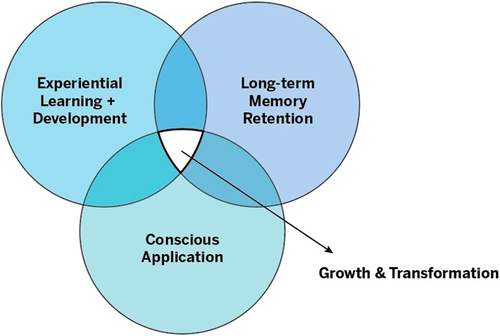

Flory posits that from a neuroscience perspective, educating and training people in “how to regulate cognition, emotion and behavior in specific circumstances,” thereby deliberately activating specific neural networks, is essential for long-term memory retention and intelligent exploration leading to clarity, coupled with relevant and appropriate expression of empathy, creative thinking, and creativity. The following diagram (Figure 3) depicts how designing a multilevel learning experience can lead to long-term memory retention and relevant creative application.

The figure clearly demonstrates the implications and importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration between neuroscience and design, and it provides an opportunity for the introduction of new methods and materials in research, teaching, and personal and global change management programs.

4.3 Formalizing definitions and a pilot test

An integral part of the research was formalizing definitions for EMP, CLA, and CRE in relation to leadership (Table 1) to enable understanding of their multiple applications in enterprise and education, not as abstract concepts or principles, but as spectra of capacities and attributes that can be exercised and developed.

This was considered a stepping-stone in the research process because the precision required to develop tight definitions for the subject of research “feeds back into the research process, provides a jumping off point for further investigation, and can also be a valuable output of research” (Haynes et al. 2015:146). The process involved a methodical review of the literature of neuroscience and organizational development of CL, and feedback and insights from the research activities described in this section.

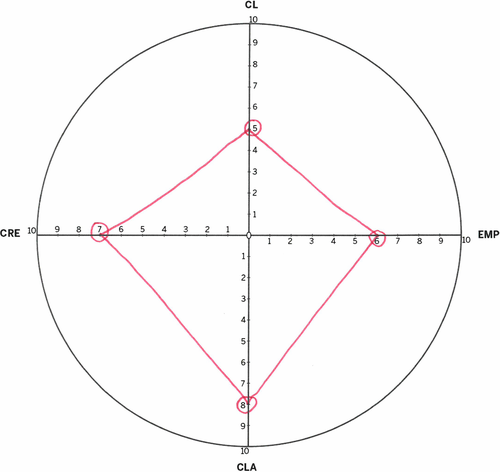

In 2018, Flory designed a pilot study to assess whether a mixed-sector group of individuals could relate to EMP, CLA, and CRE as traits and behaviors that they could identify in themselves in relation to their day-to-day work life and leadership, based on the above definitions. A simple visual tool (Figure 4) was given to participants to plot a self-assessment of personal application of these traits in the workplace.

The pilot study was implemented at Innovation for All 2018, an ID conference for business and the public sector hosted by Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA) in Oslo. A major advantage of running this mini pilot was that participants represented an opportunistic sample (N = 36; Male = 16; Female = 20). Consequently, an unintended but valuable outcome of the pilot was the discovery of relatability to these traits across sectors, in diverse leadership and organizational cultures, and their reported application in everyday personal and professional settings.

This led to a proposition for a three-dimensional model of CL that will form the basis for KPI measurement and a comprehensive multilevel approach to education and training in these leadership attributes.

4.4 Qualitative interviews

In 2018, Ivanova joined the CL research to help grow and capture the evidence base for Gheerawo’s CL model. This included a series of interviews with leaders and senior management across the public, private, and government sectors (Ivanova, 2018). The first set of semi-structured interviews examined the organizational culture and leadership style, ideas of “great” leadership and role models, and whether components of CL were partially or fully in practice in the six organizations specifically chosen for this research.3

Findings from these interviews indicated a shared recognition of changing organizational culture where enabling others to fulfill their potential, a coaching rather than directive approach, breaking down siloes, and incorporating play and experimentation to spark creativity were paving the way for new modes of leadership based on collaboration, inclusion, disruption, and accountability (Ivanova, 2019).

Empathy, while highlighted in the recent literature as a core capability of 21st-century leadership, was still misunderstood, or underappreciated, by dismissing it as a “soft skill” rather than a key attribute. For example, male leaders reported that they recognized the need for diversity in senior management and at the board level; however, they struggled to imagine or implement a long-term plan of action because of lack of prior experience with more inclusive setups and empathy-driven approaches. In contrast, aspects of clarity, such as the importance of setting a vision and being a good communicator, were well appreciated among the interviewees, with CEOs creating platforms that enabled them to communicate company vision and strategy across the organization, as well as implementing feedback loops and processes.

4.4.1 Overcoming barriers

These interviews supported an ongoing area of research interest that is mapping barriers to CL—ranging from internal barriers (e.g., egocentric mindset, lack of understanding of self-worth and value) and emotional barriers (e.g., fear and stress) to external factors (e.g., time, resources, and technology). This is where the pairing of design and neuroscience can enable development and upskilling on a personal level, where “quick-fix” solutions would prove unsustainable in the longer term. Flory asserts that exercising EMP, CLA, and CRE in thought, behavior, and emotion entrains functional changes in the brain. Continued practice and contextual application of EMP, CLA, and CRE could lead to these attributes becoming part of a person’s makeup and contribute to overall intelligence.

In design, this creates scope to develop design processes and tools for individual and group practice, as well as interventions that could enable daily stimulation and exercising of CL components through ethical integration in technological and environmental solutions.

4.5 Creative leadership in innovation

Although the core application of this model has been in executive education and human capital development, a review of CL project archives strongly indicates scope for applications of CL beyond executive education. Particularly in areas of design and innovation that address human performance and well-being, the very same three CL attributes—EMP, CLA, and CRE—can guide decision making regarding the design solution, technological and economic considerations, and individual and group experience and interaction that ensue.

CL was born from design and practice, and it not only continues to find expression within the work of HHCD but also proposes a framework for project delivery and innovation (Ivanova, Gheerawo, Poggi, Gadzheva, and Ramster, 2020). A recent proposal looking at “building competitive and resilient economies and societies through responsible AI” brought together a multidisciplinary team, including designers, human-factor specialists, robot ethicists, AI developers, neuroscientists, and economists to roadmap new people-centered pathways for AI. The main purpose was to explore how CL could inform a framework for development and assessment of AI technologies, as well as ensuring that CL attributes are integrated within and consequently expressed through human–robot interactions. It was considered that guiding AI through EMP, CLA, and CRE would enable the development of powerful assessment tools and platforms for people, projects, organizations, and technologies, with a view to positively impacting performance and economic indicators and human well-being. This signified a growing opportunity area for applying CL as a model for innovating creatively leading, socially beneficial, and sustainable technologies.

5 Future vision

The next chapter in the evolutionary story of CL is a design–neuroscience collaboration looking to develop a blueprint for CL. The intention for this original research is to further inform, refine, and expand the theory, education, practice, and applications of CL, thereby establishing it as a responsive, emerging model of leadership that empowers its practitioners with capacities and capabilities to face the unknown challenges, opportunities, and emerging reality of 21st-century markets. The combination of multidisciplinary expertise, methods, and approaches, enhanced by a shared drive to add value to others and create a positive change in the world, will ensure that the very same processes that are the foundation of CL are applied in practice in the evolution of CL theory, research, and applications.

The next phase of CL research and development involves acknowledgment and witnessing of the recognition that designers and neuroscientists should be working symbiotically to advance the knowledge and applications base of research evidence resulting from the intersection of both disciplines. Design based on CL theory and practice that is informed by evidence-based neuroscience has three important implications:

- Enhancing EMP-, CLA-, and CRE-led design typologies through learning and development strategies and methodologies informed by cognitive neuroscience knowledge and research.

- Revalidating older response-oriented and adaptive teaching and learning methods and environments that are holistic and conducive to long-term memory retention and skills development. In the competitive race to digitalize training and education, these vital, lifelong neural implications are being largely ignored (The Royal Society, 2011).

- Increasing the probability of revolutionizing leadership education, skills attainment, day-to-day applications, and organizational assessment criteria and algorithms, thereby positively impacting the growth and sustainability of human, social, and orzanisational capital.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all project partners, researchers, and participants to date for their generous contributions and insights, and specifically the London Doctoral Design Centre (LDoc) for funding Ivanova’s postdoctoral research, which brought this research team together.

Biographies

Rama Gheerawo is an international and inspirational figure within design. He is a serial innovator in the fields of Inclusive Design, Design Thinking and Creative Leadership having personally led over 100 projects working internationally with governments, business, academia and the third sector. He won a ‘Hall of Fame’ award for his work at the Design Week Awards in 2019 and was named a 2018 Creative Leader by Creative Review alongside Paul Smith and Björk. Empathy is at the heart of his practice. As Director of The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design, he uses design to address society’s toughest issues from ageing and healthcare, to ability and diversity. He looks at how to instigate positive change in individuals and organisations through personal research in Creative Leadership, with workshops delivered globally to thousands of people including 700 civil servants. He is in high demand as a keynote speaker, and writes, curates exhibitions and runs workshops for audiences that range from students to business executives. Rama sits on a number of advisory boards and committees for awards, universities and organisations such as the UK Design Council, The International Association for Universal Design, UX India, the Design Management Institute and the Design Intelligence Awards. He has worked as a Visiting Professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and the Katowice Academy of Fine Art

Melanie Flory is a Founding Director of MindRheo, a consultancy intersecting neuroscience, design and systems thinking to develop people-centred business and cultural architecture for organisations-in-change. Prior to MindRheo, Melanie’s academic and clinical career involved working in multi-disciplinary teams across EMEA and USA, specialising in brain plasticity and human behaviour. With a research background in neuroconnectivity, she continues to collaborate and partner with academia and organisations to research and co-design educational content, and product and services for optimising and activating neuroplasticity to enable new learning and behavioural change. She has been neuroscience partner to The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design since 2018 and has been recently appointed Associate Research Director at the Centre.

Ninela Ivanova is an Innovation Fellow at The Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design (HHCD) at London’s Royal College of Art. She is an interdisciplinary designer, researcher and facilitator, who is passionate about working co-creatively with individuals and groups to educate and inspire audiences towards people-centred design, innovation, and transdisciplinary collaboration. Ninela leads HHCD’s Inclusive Design for Business Impact area, which looks at how the methods, tools and processes of Inclusive Design, Design Thinking and Creative Leadership can directly impact and transform business and industry

References

- 1 Volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.

- 2 Political, economic, social, technological, legal, and ethical/environmental.

- 3 Names cannot be disclosed due to the confidentiality clause in the ethics agreement.