Reliability and validity of prognostic indicators for Guillain–Barré syndrome in children

This original article is commented on by Misra on pages 448–449 of this issue.

Abstract

Aim

To explore the clinical characteristics and prognostic predictors of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) in Chinese paediatric patients.

Method

The clinical features of children with GBS hospitalized in the Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical University were summarized retrospectively. The correlation between the Erasmus GBS Outcome Score (EGOS)/modified Erasmus GBS Outcome Score (mEGOS), GBS disability score (GDS)/modified Rankin Scale (MRS), Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score (EGRIS), and mechanical ventilation were evaluated.

Results

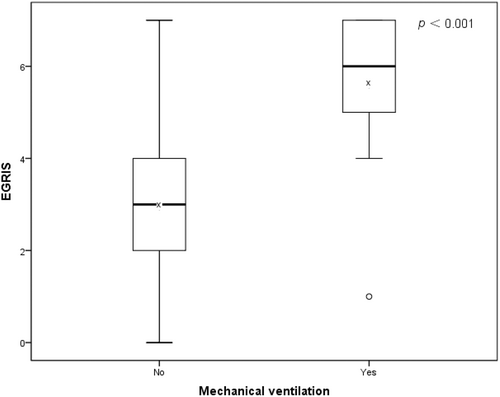

One hundred forty-two patients (86 males, 56 females; median 62.50 months [interquartile range 41.00–97.50]) with classic GBS were enrolled in the study. In the present GBS cohort, 134 (94.37%) patients could walk independently (GDS ≤2) and 121 (85.21%) could manage without assistance (MRS ≤2) at 6 months. Eighteen (12.68%) patients with GBS required mechanical ventilation. The performance of mEGOS on admission, mEGOS on day 7, and EGOS-predicted GDS outcome at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months in the paediatric patients with GBS admitted within 2 weeks of disease onset and that of the MRS outcome were evaluated. The EGRIS in individuals who required mechanical ventilation was significantly higher than in patients without mechanical ventilation (median = 6 vs median = 3, p < 0.001).

Interpretation

In Chinese paediatric patients with GBS who were admitted 2 weeks after disease onset, the mEGOS and EGOS are validated indicators for the prediction of clinical outcomes 6 months after onset. EGRIS is helpful in predicting the implementation of mechanical ventilation in the acute phase.

What this paper adds

- The Erasmus Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) Outcome Score (EGOS) and modified EGOS are reliable prognostic predictors in paediatric patients with GBS.

- The Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score (EGRIS) is an effective predictor of mechanical ventilation in paediatric patients with GBS.

- An EGRIS of ≥5 indicates a high risk of mechanical ventilation in the acute phase.

What this paper adds

- The Erasmus Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) Outcome Score (EGOS) and modified EGOS are reliable prognostic predictors in paediatric patients with GBS.

- The Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score (EGRIS) is an effective predictor of mechanical ventilation in paediatric patients with GBS.

- An EGRIS of ≥5 indicates a high risk of mechanical ventilation in the acute phase.

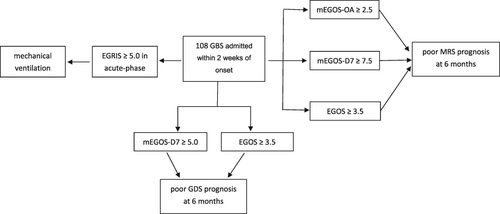

The Erasmus Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) outcome score (EGOS) and modified EGOS are reliable prognostic predictors in paediatric patients with GBS; mEGOS-D7 ≥5.0 and EGOS ≥3.5 indicate poor GDS prognosis at 6 months, and mEGOS-OA ≥2.5, mEGOS-D7 ≥7.5 and EGOS ≥3.5 for MRS.The Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score (EGRIS) is an effective predictor of mechanical ventilation in paediatric patients with GBS.An EGRIS ≥5 indicates a high risk of mechanical ventilation in the acute phase.

This original article is commented on by Misra on pages 448–449 of this issue.

Abbreviations

-

- AUC

-

- area under the receiver operating characteristic

-

- GBS

-

- Guillain–Barré syndrome

-

- GDS

-

- GBS disability score

-

- EGOS

-

- Erasmus GBS Outcome Score

-

- EGRIS

-

- Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score

-

- mEGOS

-

- modified Erasmus GBS Outcome Score

-

- MRS

-

- modified Rankin Scale

Guillain–Barré Syndrome (GBS) is a worldwide acute inflammatory polyneuropathy that was first described in 1916 by Georges Guillain, Jean Alexandre Barré, and André Strohl.1 Individuals with GBS typically present with rapidly progressive ascending symmetrical flaccid paralysis associated with reduced or absent reflexes. GBS has an annual global incidence of approximately 1 to 2 per 100 000 person-years with a wide range of reported incidence in different countries.2 Compared to North America, Latin America, and Europe, population-based studies in East Asia reported lower incidence of GBS with 0.67 cases per 100 000 person-years in China.3, 4 The annual incidence of GBS has been estimated to be between 0.34 and 1.34 per 100 000 person-years in children younger than 15 years old.5, 6

Most patients with GBS have an antecedent event up to 4 weeks before developing neurological manifestations. In the International GBS Outcome Study, 76% of patients had an antecedent event.7 GBS has a monophasic clinical course, although treatment-related fluctuations and relapses occur in a minority of patients. Almost all patients reached the lowest disease nadir within 4 weeks; thereafter, recovery was slow.8 In paediatric patients in the peak phase of GBS, 75% can no longer walk unaided.9

The overall prognosis in GBS is good but approximately 20% of patients with GBS remain disabled; 60% to 80% of patients with GBS can walk independently 6 months after disease onset.4, 6, 10, 11 Up to 20% to 30% of patients with GBS require mechanical ventilation during the acute phase and death occurs in 3% to 10% of cases, most commonly because of respiratory failure and dysautonomia.11-13 Available clinical scales should be used to describe ‘impairment’ (Medical Research Council) and ‘activity and participation’ (GBS score and modified Rankin Scale [MRS]) at disease onset and during the peak and recovery phases of GBS.9

Prognostic prediction is very important for patients with GBS when deciding on the need to escalate the therapy that may benefit patients with poor prognoses. Several prognostic models of GBS have been developed. The Erasmus GBS Outcome Score (EGOS) and modified EGOS (mEGOS) developed by the Dutch Erasmus GBS group are used to predict the probability of walking independently at 6 months.14 The Dutch Erasmus GBS group also developed the Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score (EGRIS) to predict the probability of early mechanical ventilation.15 EGOS is based on age, presence of diarrhoea, and GBS disability score (GDS) at day 14 of hospital admission.16 However, mEGOS is based on age, presence of diarrhoea, and Medical Research Council summary score on admission and at day 7 of hospital admission.17 EGRIS is based on the duration of weakness before hospital admission, facial and/or bulbar weakness, and Medical Research Council summary score on admission.15

The EGOS/mEGOS and EGRIS models have been validated in adults. However, there is no application of this model in the paediatric population with GBS. In the current study, we aimed to validate prognostic prediction with EGOS/mEGOS and EGRIS in Chinese paediatric patients with GBS.

METHOD

Children fulfilling the 2015 diagnostic criteria18 for GBS with outcome data available at 6 months were included (Figure S1). All were admitted to the Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China from February 2015 to January 2021. The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical University Institutional Review Board (no. 2021) (ethical review [research] no. 81). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants or their caregivers.

Basic details and disease-relevant history were noted, such as age at onset of first symptoms, sex, duration from onset to admission, and antecedent events. The Medical Research Council summary score (Video S1), EGOS, mEGOS on admission and at day 7 of admission, and EGRIS on admission were also recorded. Mechanical ventilation, tracheotomy, and treatment were recorded simultaneously. Children with GBS were assessed according to the GDS and MRS at three time points: 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months. Individuals were considered as having a good outcome when the GDS was ≤2 and a poor outcome when the GDS was >2; the outcome for the MRS was the same as for the GDS.19

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS v17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). An independent t-test was used for continuous variables and a Fisher's exact test for categorical variables respectively. A Mann–Whitney U test was performed if the assumption of normality was not met. A Pearson correlation test was used to evaluate the correlation between GDS/MRS and EGOS/mEGOS, as well as the correlation between mechanical ventilation and EGRIS. Spearman's correlation was used for data that were not normally distributed. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was done to assess prognostic prediction (EGOS/mEGOS for GDS and MRS; EGRIS for mechanical ventilation); p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 142 patients with classic GBS were enrolled between February 2015 and January 2021.

In the GBS cohort, 86 (60.56%) were male and 56 (39.44%) female (male-to-female ratio approximately 1.5). One hundred forty (98.59%) individuals were treated whereas two (1.41%) individuals were not treated. The two untreated children were admitted over 2 weeks after disease onset and had mild GBS; they could walk independently and manage without assistance. The epidemiological and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| GBS (n = 142) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n (%) |

Median (IQR), mean (SD) |

|

| Sex | ||

| Males | 86 (60.56) | |

| Females | 56 (39.44) | |

| Age (months) | 62.50 (41.00, 97.50) | |

| 71.18 (43.01) | ||

| <12 | 4 (2.82) | |

| 12–36 | 27 (19.01) | |

| 36–72 | 55 (38.73) | |

| 72–144 | 46 (32.39) | |

| >144 | 10 (7.04) | |

| Antecedent events | ||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 63 (44.37) | |

| Pneumonia | 16 (11.27) | |

| Diarrhoea | 12 (8.45) | |

| Vaccination | 4 (2.82) | |

| Trauma | 3 (2.11) | |

| None | 44 (30.99) | |

| Duration from disease onset to admission (days) | 7.00 (4.00, 14.00) | |

| 11.30 (12.51) | ||

| <14 | 108 (76.06) | |

| 14–28 | 22 (15.49) | |

| >28 | 12 (8.45) | |

| GDS | ||

| On admission | 4.00 (3.00, 4.00) | |

| 3.39 (0.92) | ||

| 3–6 | 112 (78.87) | |

| 0–2 | 30 (21.13) | |

| At 6 months | 1.00 (0, 1.25) | |

| 0.85 (1.01) | ||

| 3–6 | 8 (5.63) | |

| 0–2 | 134 (94.37) | |

| MRS | ||

| On admission | 4.00 (3.00, 4.00) | |

| 3.76 (0.83) | ||

| 3–6 | 130 (91.55) | |

| 0–2 | 12 (8.45) | |

| At 6 months | 1.00 (0, 2.00) | |

| 1.05 (1.20) | ||

| 3–6 | 21 (14.79) | |

| 0–2 | 121 (85.21) | |

| mEGOS on admission | 142 | 2.00 (2.00, 4.00) |

| 3.20 (1.98) | ||

| mEGOS on day 7 of admission | 142 | 3.00 (3.00, 6.00) |

| 3.96 (2.95) | ||

| EGOS | 142 | 3.00 (3.00, 4.00) |

| 3.16 (1.01) | ||

| EGRIS | 142 | 3.00 (1.00, 4.00) |

| 2.85 (1.99) | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 18 (12.68) | |

| Tracheotomy | 9 (6.34) | |

| Treatment | ||

| IVIG | 115 (80.99) | |

| Plasma exchange | – | |

| Intensive therapy | 25 (17.61) | |

| IVIG ×2 | 6 (4.23) | |

| IVIG + glucocorticoida | 10 (7.04) | |

| IVIG + plasma exchange | 4 (2.82) | |

| IVIG ×2 + glucocorticoid | 3 (2.11) | |

| IVIG×2 + glucocorticoid + plasma exchange | 2 (1.41) | |

| No treatment | 2 (1.41) | |

- a Small doses for short periods of less than 1 week. Abbreviations: EGOS, Erasmus GBS Outcome Score; EGRIS, Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; GDS, GBS disability score; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; IQR, interquartile range; mEGOS, modified Erasmus GBS Outcome Score; MFS, Miller Fisher syndrome; MRS, modified Rankin Scale.

A comparison was made between patients admitted within 2 weeks (108 patients) and 2 to 4 weeks (22 patients) after disease onset and is shown in Table 2.

| GBS admitted within 2 weeks after onset (n = 108) | GBS admitted within 2–4 weeks after onset (n = 22) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Median (IQR) | n (%) | Median (IQR) | ||

| GBS disability score | |||||

| On admission | 4.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 3.00) | <0.001 | ||

| 3–6 | 90 (83.33) | 15 (68.18) | |||

| 0–2 | 18 (16.67) | 7 (31.82) | 0 (0, 1.25) | 0.402 | |

| At 6 months | 1.00 (0, 1.00) | ||||

| 3–6 | 5 (4.63) | 1 (4.55) | |||

| 0–2 | 103 (95.37) | 21 (95.45) | |||

| MRS | |||||

| On admission | 4.00 (3.25, 4.00) | 3.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 0.001 | ||

| 3–6 | 103 (95.37) | 18 (81.82) | |||

| 0–2 | 4 (18.18) | 0.463 | |||

| At 6 months | 5 (4.63) | ||||

| 3–6 | 1.00 (0, 2.00) | 3 (13.64) | |||

| 0–2 | 15 (13.89) | 19 (86.36) | |||

| 93 (86.11) | 0 (0, 2.00) | ||||

| mEGOS on admission | 108 | 4.00 (2.00, 6.00) | 22 | 2.00 (0, 2.00) | <0.001 |

| mEGOS on day 7 | 108 | 3.00 (3.00, 6.00) | 22 | 3.00 (0, 3.00) | <0.001 |

| EGOS | 108 | 3.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 22 | 3.00 (2.00, 3.00) | 0.001 |

| EGRIS | 108 | 3.00 (2.00, 5.00) | 22 | 1.00 (0, 1.00) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 17 (15.74) | 1 (4.55) | 0.201 | ||

| Tracheotomy | 9 (8.33) | 0 (0) | 0.222 | ||

- Abbreviations: EGOS, Erasmus GBS Outcome Score; EGRIS, Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; IQR, interquartile range; mEGOS, modified Erasmus GBS Outcome Score; MRS, modified Rankin Scale.

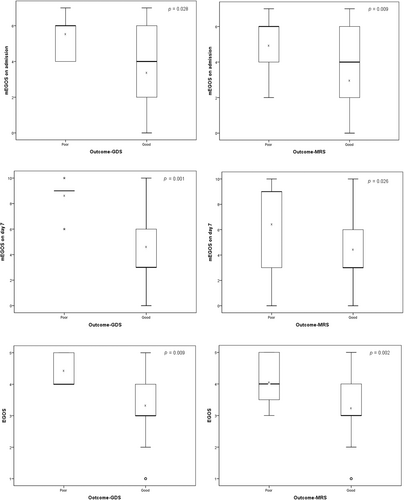

One hundred eight patients with GBS admitted within 2 weeks after disease onset were included for the analyses of the GDS outcome (Table 3). The mEGOS on admission, mEGOS on day 7, and EGOS in patients with good GDS outcomes were significantly lower than those in patients with poor GDS outcomes (median = 4.00 vs median = 6.00, p = 0.028; median = 3.00 vs median = 9.00, p = 0.001; median = 3.00 vs median = 4.00, p = 0.009) (Figure 1). The performance of the mEGOS on admission, mEGOS on day 7, and EGOS was good in predicting GDS outcome at the three time points (on admission: area under the receiver operating characteristic [AUC] curve = 0.820 [95% confidence interval {CI} 0.741–0.899], 0.805 [95% CI 0.717–0.892], and 0.776 [95% CI 0.614–0.937]; day 7 of admission: AUC = 0.834 [95% CI 0.757–0.911], 0.829 [95% CI 0.741–0.917], and 0.879 [95% CI 0.778–0.979]; day 14 of admission: AUC = 0.882 [95% CI 0.819–0.944], 0.862 [95% CI 0.790–0.933], and 0.826 [95% CI 0.702–0.950]).

| 4 weeks | 3 months | 6 months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | AUC (95% CI) | r | p | AUC (95% CI) | r | p | AUC (95% CI) | |

| mEGOS on admission | 0.62 | <0.001 | 0.820 (0.741–0.899) | 0.56 | <0.001 | 0.805 (0.717–0.892) | 0.47 | <0.001 | 0.776 (0.614–0.937) |

| mEGOS on day 7 | 0.72 | <0.001 | 0.834 (0.757–0.911) | 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.829 (0.741–0.917) | 0.51 | <0.001 | 0.879 (0.778–0.979) |

| EGOS | 0.82 | <0.001 | 0.882 (0.819–0.944) | 0.66 | <0.001 | 0.862 (0.790–0.933) | 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.826 (0.702–0.950) |

- Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; EGOS, Erasmus GBS Outcome Score; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; GDS, GBS disability score; mEGOS, modified EGOS.

The performance of the MRS outcomes of 108 patients with GBS was also assessed in the study (Table 4). The mEGOS on admission, mEGOS on day 7, and EGOS in patients with good MRS outcomes were significantly lower than those in patients with poor MRS outcomes (median = 4.00 vs median = 6.00, p = 0.009; median = 3.00 vs median = 9.00, p = 0.026; median = 3.00 vs median = 4.00, p = 0.002) (Figure 1). The results of the mEGOS on admission, mEGOS on day 7, and EGOS was good at predicting MRS outcome at all three time points after GBS onset (admission: AUC = 0.836 [95% CI 0.761–0.910], 0.792 [95% CI 0.706–0.878], and 0.700 [95% CI 0.569–0.830]; day 7 of admission: AUC = 0.786 [95% CI 0.699–0.874], 0.805 [95% CI 0.715–0.896], and 0.668 [95% CI 0.498–0.839]; day 14 of admission: AUC = 0.838 [95% CI 0.759–0.918], 0.832 [95% CI 0.756–0.909], and 0.732 [95% CI 0.602–0.863]).

| 4 weeks | 3 months | 6 months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | AUC (95% CI) | r | p | AUC (95% CI) | r | p | AUC (95% CI) | |

| mEGOS on admission | 0.64 | <0.001 | 0.836 (0.761–0.910) | 0.59 | <0.001 | 0.792 (0.706–0.878) | 0.47 | <0.001 | 0.700 (0.569–0.830) |

| mEGOS on day 7 | 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.786 (0.699–0.874) | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.805 (0.715–0.896) | 0.43 | <0.001 | 0.668 (0.498–0.839) |

| EGOS | 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.838 (0.759–0.918) | 0.68 | <0.001 | 0.832 (0.756–0.909) | 0.52 | <0.001 | 0.732 (0.602–0.863) |

- Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; EGOS, Erasmus GBS Outcome Score; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; mEGOS, modified EGOS; MRS, modified Rankin Scale.

For further illustration, patients with GBS admitted within 2 weeks of disease onset were divided into two groups according to mEGOS on admission, mEGOS on day 7, and EGOS; the cut-off points were selected according to the Youden index. An mEGOS on admission ≥2.5 indicated a poor MRS outcome at 6 months (odds ratio [OR] = 5.590 [95% CI 1.194–26.166], p = 0.022). A mEGOS on day 7 ≥ 5.0 indicated a poor GDS outcome at 6 months (OR = 1.135 [95% CI 1.016–1.269], p = 0.008). An mEGOS on day 7 ≥ 7.5 indicated a poor MRS outcome at 6 months (OR = 5.109 [95% CI 1.630–16.017], p = 0.006). An EGOS ≥3.5 indicated a poor outcome according to the GDS and MRS at 6 months (GDS: OR = 1.116 [95% CI 1.014–1.229], p = 0.015; MRS: OR = 4.162 [95% CI 1.232–14.061], p = 0.023) (Table 5).

| GDS | MRS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | OR (95% CI) | p | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | OR (95% CI) | |

| mEGOS on admission | 0.062 | 3.5 | 5/5 | 49/103 | 1.093 (1.011–1.181) | 0.022 | 2.5 | 13/15 | 43/93 | 5.590 (1.194–26.166) |

| mEGOS on day 7 | 0.008 | 5.0 | 5/5 | 66/103 | 1.135 (1.016–1.269) | 0.006 | 7.5 | 8/15 | 76/93 | 5.109 (1.630–16.017) |

| EGOS | 0.015 | 3.5 | 5/5 | 60/103 | 1.116 (1.014–1.229) | 0.023 | 3.5 | 11/15 | 56/93 | 4.162 (1.232–14.061) |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EGOS, Erasmus GBS Outcome Score; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; GDS, GBS disabiilty score; mEGOS, modified EGOS; MRS, modified Rankin Scale; OR, odds ratio.

Seventeen (15.74%) patients admitted within 2 weeks after disease onset required mechanical ventilation. EGRIS in individuals who required mechanical ventilation was significantly higher than in patients without mechanical ventilation (median = 6.00 vs median = 3.00, p < 0.001) (Figure 2). EGRIS performed well in predicting the requirement for mechanical ventilation in the acute phase of the disease in patients with GBS (AUC = 0.888 [95% CI 0.787–0.990]). In the high-risk subgroup (EGRIS 5–7), 15 patients developed respiratory insufficiency, which required mechanical ventilation, while only two patients in the low-risk subgroup (EGRIS 0–4) (OR = 38.000 [95% CI 7.859–183.734], p < 0.001) required mechanical ventilation (Table 6).

| Mechanical ventilation | p | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| Low risk (EGRIS 0–4) | 76 | 2 | <0.001 | 38.000 (7.859–183.734) | |

| High risk (EGRIS 5–7) | 15 | 15 | |||

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EGRIS, Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; OR, odds ratio.

In the 22 patients admitted within 2 to 4 weeks after disease onset, 21 could walk independently (GDS ≤2) at 6 months (n = 1 with GDS = 3). Nineteen patients could manage without assistance (MRS ≤2) and three with an MRS >2 failed to do so; two patients had an MRS of 3 and one had an MRS of 4. At 6 months after disease onset, there was no significant correlation between mEGOS on admission, mEGOS on day 7, and EGOS with GDS outcomes (mEGOS on admission: r = 0.01, p = 0.983; mEGOS on day 7: r = −0.26, p = 0.248; EGOS: r = 0.20, p = 0.376). The same applies to the MRS outcomes (mEGOS on admission: r = 0.01, p = 0.982; mEGOS on day 7: r = −0.20, p = 0.374; EGOS: r = −0.25, p = 0.258).

DISCUSSION

The mean age of the 142 children with GBS was approximately 5 years 11 months, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.5, which is in agreement with previous studies of a peak incidence of 6 years and a male-to-female ratio of 1.2 to 1.5.20-26 However, the epidemiological characteristics of GBS are slightly different in different regions. We speculate that differences are the result of the interaction of various factors, such as environmental characteristics, antecedent events, and varying genetic polymorphisms between populations in different regions or countries.26

In addition to upper respiratory tract infections and diarrhoea found in 44.37% and 8.45% of patients with GBS respectively, other antecedent events included trauma and vaccinations. In Europe, 22.7% had diarrhoea and 36.8% had upper respiratory tract infections, while this was 16.02% for diarrhoea and 49.03% for upper respiratory tract infections in Brazil.27 No antecedent event was documented in approximately 30.99% of patients with GBS both in our study and previous ones. In addition, the most common antecedent events may be different in northern and southern China. In northern China, infection with Campylobacter jejuni was the predominant antecedent event, whereas upper respiratory tract infections were most prevalent in southern China.24, 28

The clinical outcomes of paediatric GBS can be variable and an early prognosis is crucial for children with a poor clinical outcome who may benefit from therapy escalation. Use of the GDS and MRS is recommended to describe ‘activity and participation’ and monitor the disease course of GBS. Our study showed that higher mEGOS and EGOS were significantly correlated with poor GDS and MRS outcomes in Chinese paediatric patients with GBS admitted within 2 weeks after disease onset. An mEGOS on day 7 ≥ 5.0 and an EGOS ≥3.5 indicated a poor GDS outcome at 6 months; an mEGOS on day 7 ≥ 2.5, an mEGOS on day 7 ≥ 7.5, and an EGOS ≥3.5 indicated a poor MRS outcome at 6 months. However, the findings are only applicable to children with classic GBS admitted within 2 weeks of disease onset and not to those admitted over 2 weeks of disease onset. Based on our findings, higher levels of mEGOS and EGOS can be used to predict poor prognosis in patients.

Our findings are slightly different from the results of previous reports in adults.10, 16, 19 Compared to Japanese and Malaysian studies of adult patients with GBS,10, 19 the mEGOS on admission (median = 4.0) in our participants was comparable to that in Malaysian patients with GBS (mean = 4.0) and slightly higher than in Japanese patients (mean = 3.3); the mEGOS on day 7 (median = 3.0) in our participants was lower than in Japanese and Malaysian patients with GBS (mean = 4.4 and mean = 5.4 respectively). GDS outcomes were favourable in our study and in the Japanese study, compared to the Malaysian study; 6 months after disease onset, 95.37% of our patients and 89% of Japanese patients could walk independently (GDS ≤2) compared to 30.8% in the Malaysian study. At the same time, 86.11% of our patients with GBS could manage without assistance (MRS ≤2) at 6 months. The EGOS (median = 3.0) in our participants was lower than in the Malaysian adult patients (mean = 4.3), suggesting that EGOS was also effective in predicting clinical outcomes in our cohort with GBS. Similarly, the EGOS showed very good discriminative ability (AUC = 0.85) in a European study.16 The mEGOS prognostic model was proved to be valid in the Netherlands (on admission: AUC = 0.73–0.77; day 7 of admission: AUC = 0.84–0.87).17 Unlike our study, the EGOS at 6 months after disease onset, as an indicator, was less marked in the Brazilian cohort; only 24% of patients with the highest EGOS score (5.5–7) were unable to walk independently while this was 52% in European patients.27 These differences suggest that age, different infection profiles, and genetic polymorphisms between populations may play roles in GBS outcomes.

We also found that EGRIS was significantly higher in patients in our cohort who required mechanical ventilation, which is consistent with previous studies in northern India and Japan.6, 19 In our study, the median EGRIS was 6.0 in 17 patients with ventilator support, compared to a median EGRIS of 4.3 in the Japanese study. Based on our results and previous studies,6,15,19,29 clinicians should be highly vigilant of respiratory failure and ready to start mechanical ventilation in patients with an EGRIS ≥5.

Our study has some limitations. First, this was a single-centre, retrospective study restricted to southwestern China (Chongqing). Second, because the Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical University is a regional paediatric medical centre, potential cases with mild phenotype might have been excluded because they had no need to visit this hospital. Therefore, a prospective, observational, multicentre cohort study is needed to further evaluate the prognostic models.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the EGOS and mEGOS are valid models for predicting GBS outcomes at 6 months after disease onset and that the EGRIS is helpful in predicting the requirement for mechanical ventilation in patients during the acute phase, in the context of a paediatric population in China.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients and their families, and the help provided by all physicians in the course of medical treatment.

The authors have stated they had no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

None