Randomized controlled trial of a home-visiting intervention on infant cognitive development in peri-urban South Africa

Abstract

Aim

To determine whether, in an impoverished South African community, an intervention that benefitted infant attachment also benefitted cognitive development.

Method

Pregnant females were randomized to intervention (n=220) and no-treatment control groups (n=229). The intervention was home-based parenting support for attachment, delivered until 6 months postpartum. At 18 months, infants were assessed on attachment and cognitive development (Bayley Scales Mental Development Index [MDI]) (n=127 intervention, n=136 control participants). Infant MDI was examined in relation to intervention, socio-economic risk, antenatal depression, and infant sex and attachment.

Results

Overall, there was little effect of the intervention on MDI (p=0.094, d=0.20), but there was an interaction between intervention and risk (p=0.03,  =0.02). MDI scores of infants of lower risk intervention group mothers were, on average, 4.84 points higher than those of other infants (p=0.002, d=0.41). Antenatal depression was not significant once intervention and risk were controlled (p=0.08); there was no association between infant MDI and either sex (p=0.41) or attachment (p=0.56).

=0.02). MDI scores of infants of lower risk intervention group mothers were, on average, 4.84 points higher than those of other infants (p=0.002, d=0.41). Antenatal depression was not significant once intervention and risk were controlled (p=0.08); there was no association between infant MDI and either sex (p=0.41) or attachment (p=0.56).

Interpretation

Parenting interventions for infant cognitive development may benefit from inclusion of specific components to support infant cognition beyond those that support attachment, and may be most effective for infants over 6 months. They may need augmentation with other input where adversity is extreme.

What this paper adds

- Intervention that benefits attachment might not benefit cognition.

- Conditions of socio-economic adversity might limit cognitive benefits of intervention.

- In adverse conditions, psychological interventions for cognition may need augmentation.

- Cognitive interventions might be more effective with older infants.

This article is commented on by Grantham-McGregor on pages 222–223 of this issue.

Abbreviation

-

- MDI

-

- Mental Development Index

Raised rates of parenting difficulties occur in the context of the poverty and mental health problems that are commonly seen in low- and middle-income countries.1, 2 These are, in turn, associated with problems in infant psychological development (e.g. insecure attachment and poor cognitive functioning).3 These early developmental difficulties are important, since they tend to persist and they predict a range of problems that affect children's life course trajectories (e.g. conduct disorder, educational failure, and employment prospects).4 Consequently, interventions are needed that target parenting in infancy. Moreover, in the context of low- and middle-income countries, it is important that interventions are affordable and use readily available resources. In our earlier epidemiological work in a disadvantaged peri-urban settlement in South Africa (Khayelitsha), we found high rates of maternal depression, parenting difficulties, and insecure infant attachment.3, 5 Subsequently, in a randomized controlled trial we demonstrated benefits to these outcomes of a home-visiting programme, delivered by lay community workers from late pregnancy through the first 6 months postpartum.6

An important question is whether the benefit of our intervention to infant attachment security extended to other infant psychological outcomes, and in particular cognitive development. Establishing the limits of the effectiveness of interventions, as well as their benefits, is important in informing policy and practice. Child cognitive performance in South Africa is of considerable concern: in 2011 fewer than half of grade 3 children achieved the basic educational level considered acceptable,7 and in an international review of literacy in 9- to 10-year-old children, including several low- and middle-income countries, South Africa was last in the performance table.8

Child cognitive performance from late infancy is a good predictor of later cognitive functioning.4 If our intervention did indeed benefit infant cognitive functioning as well as attachment security, this would argue for it being implemented without substantial modification, in order to be of relatively general benefit to infant psychological development. Notably, however, our intervention was targeted at caretaking with particular relevance to attachment (e.g. responsiveness to infant distress), and its benefit to domains of infant functioning such as cognitive performance may have been more limited. Indeed, there is increasing recognition of the specificity of associations between different parenting qualities and particular child outcomes.9, 10 Of special relevance to the question addressed here are findings that the parenting qualities most relevant to attachment (protection and comforting when infants are distressed or vulnerable) do not necessarily predict child cognitive outcome and, vice versa, that parental support for child cognitive achievements (e.g. scaffolding and guided learning) does not necessarily promote socio-emotional developments such as attachment security.9, 10 Notably, effective interventions for infant and child cognitive outcome in low- and middle-income countries11-13 have often involved parents being coached in active play and stimulation of their child, and far less evidence is available concerning the cognitive benefits of non-cognitively focused parenting curricula, particularly for children under 2 years of age. The current paper addresses this question. We report the effects of our intervention on infant performance on a standard measure of infant cognitive development, the Mental Development Index (MDI) of the Bayley II Scales.14 This was assessed concurrently with attachment security at 18 months.

Studies of interventions for child development, including cognitive outcomes, have found background risk to be relevant. In high-income countries, benefits of home-visiting are particularly clear in the context of greater socio-economic risk.15 However, although such associations have been found in low- and middle-income countries or generally disadvantaged populations,11 there is some evidence that those at greatest risk (e.g. through low education) may benefit less from parenting programmes.1, 11, 16 Such differential effects are important to determine so that interventions can be targeted appropriately. In Khayelitsha, despite poverty being ubiquitous, living conditions vary (e.g. in the provision of water, electricity), and therefore we examined whether intervention effects differed according to the level of socio-economic risk.

In addition to postnatal influences on child cognitive development, antenatal depression has been found to pose a direct risk,17 and so we investigated its effects too. Furthermore, since some studies report cognitive development in male infants to be more vulnerable to effects of adversity than female infants,18 we investigated direct and moderating effects of infant sex. Finally, given the specificity of parenting effects on different aspects of child psychological development, we examined associations between infant cognitive outcome and attachment security.

Method

Design

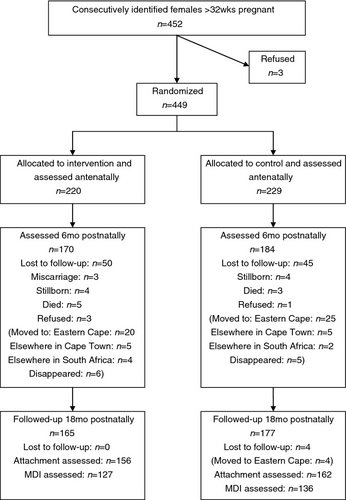

The study design has been described in detail in our previous report on the effects of our intervention on infant attachment5 (Trial registration number: ISRCTN25664149). The CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure 1. It was conducted in two adjoining areas (‘SST’ and ‘Town II’) in Khayelitsha, a disadvantaged peri-urban settlement near Cape Town, South Africa. SST is an informal settlement characterized by high levels of unemployment (two-thirds of the population) and poverty (shacks without electricity or running water); in Town II the standard of living is somewhat better. The study was a randomized controlled trial in which pregnant females were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or a no treatment control group. The intervention was delivered in mothers’ homes by trained community workers from the third trimester of pregnancy until 6 months postpartum. Infant cognitive development was independently assessed at 18 months. The study was approved by the research ethics committees of the University of Reading and the Health Sciences faculty of the Medical School of the University of Cape Town, and participants gave written informed consent.

Participants

House-to-house visits were made at 3-weekly intervals in the study area over a 22-month period. A total of 452 pregnant females were invited to participate in the study; all but three agreed. After the females gave consent, demographic variables and socio-economic risk factors were recorded, and mothers were randomly assigned to either the intervention (n=220) or control group (n=229) by minimization, balancing for antenatal depression, planned pregnancy, and housing area (see Fig. 1). We anticipated substantial participant loss because many mothers travel from rural areas to deliver their infants, and then return; indeed, approximately one-fifth of the sample could not be followed-up because mothers moved away, or their infants died (see Fig. 1). Of those originally enrolled, 342 (76%) were assessed at 18 months (n=165 in the intervention group, n=177 in the control group). Of these, attachment to the mother was assessed in 318 (93%) infants (n=156 intervention, n=162 control),6 and cognitive development was assessed in 263 infants (77%) (n=127 intervention, n=136 control).

The intervention

Four trained home visitors visited the mother twice in pregnancy, and then on 14 occasions up to 6 months postpartum (75% of mothers received all 16 visits, and over 90% received at least eight visits). Visits lasted 1 hour. The home visitors all lived in Khayelitsha and were mothers themselves. Two had completed schooling; none had education or training beyond school. The intervention was manualized.5 It included key principles of the World Health Organizations ‘Improving the Psychosocial Development of Children’19 and ‘The Social Baby’.20 It provided psychological support to the mother, using counselling and items from the Neonatal Behavioural Assessment Scale21 to enhance maternal awareness of infant social engagement and providing strategies for managing infant distress. The home visitors received 3 weeks of training in the intervention over a 4-month period, and weekly group supervision from a community clinical psychologist.

All mothers (control and intervention) received fortnightly visits by a community health worker from a local non-governmental organization who monitored maternal and infant health.

Measures

Socio-economic risk

We used socio-economic risk indices employed in previous research (adolescent parenthood, unplanned pregnancy, and <7y education)17 and indices more specific to our sample (poor partner support, lack of electricity at home, and additional children).

Antenatal depression

Antenatal depression (and depression at 2mo and 6mo) was assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnoses.22 This interview has good reliability and validity, and has been widely used in South Africa. Interviews were administered by a trained researcher and audiotaped. Diagnoses were independently confirmed with a senior clinician.

Infant cognitive development

The Bayley Scales (version II)14 was administered at 18 months and the MDI used as the measure of cognitive outcome. The assessment was conducted in research premises in Khayelitsha by a trained researcher who was blind to the group. Since the principal outcome was attachment security, this was assessed first, followed by a break. Subsequently, if the infant's state permitted, the MDI was administered.

Statistical analysis

We examined equivalence in socio-demographic characteristics between intervention and control groups using Student's t-test or χ2, as appropriate. Next, we examined relationships between individual risk factors. Given their associations, a composite was created. Then, using Analysis of Variance (ANOVAs) and Analysis of Covariance, we examined effects of the intervention on child cognitive development, including socio-economic risk as a potential moderator, as well as relevant covariates (antenatal and postnatal depression). We also explored effects of individual risk factors through further ANOVAs, and bivariate correlations using bootstrapping with bias correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. Adjusted standard errors and adjusted confidence intervals are provided. Equality of variances was tested through Levene′s test, and in all cases data met assumption criteria. Finally, in secondary analyses, we examined effects (main and potential moderating) of infant sex, and whether infant cognitive development and attachment security showed the same pattern of relationship to treatment and risk and whether they were associated with each other. Effect sizes were computed, with d being calculated for main effects and partial eta-squared ( ) for ANOVA interactions.

) for ANOVA interactions.

Results

Participant characteristics

The demographics and risk factors are shown in Table 1. The current sample did not differ from those originally recruited, nor from all those with attachment assessments. Infant attachment for the slightly smaller sample with cognitive assessments showed the same benefit of the intervention as the full sample (Wald=7.8, df=1, OR=2.2 [95% CI=1.3–3.8], p=0.005). There were no differences at base line in demographic and risk factors between intervention and control groups but, as predicted, at 2 months postpartum, compared to control group mothers, fewer intervention group mothers were depressed.

| Intervention n=127 | Control n=136 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mother and family socio-demographics (%) | ||

| Maternal age | ||

| Mean (95% CI) | 25.6 (24.6–26.6) | 26.6 (25.5–27.6) |

| Range | 15–39 | 16–43 |

| Adolescent mothera | 24 (19) | 27 (20) |

| Maternal education | ||

| Educated for ≤6ya | 35 (28) | 41 (30) |

| Marital status and support | ||

| Married | 56 (44) | 60 (44) |

| No partner supporta | 31 (25) | 29 (21) |

| Maternal depression | ||

| Antenatal | 24 (19) | 27 (20) |

| 2mo postnatal | 23 (19) | 39 (30) |

| 6mo postnatal | 13 (11) | 22 (18) |

| Housing | ||

| No electricitya | 69 (54) | 70 (51) |

| Living area | ||

| SST | 71 (56) | 72 (53) |

| Town II | 56 (44) | 64 (47) |

| Pregnancy history and child characteristics | ||

| Planned pregnancy | ||

| Unplanned pregnancya | 52 (41) | 50 (37) |

| Other children | ||

| Not primiparousa | 68 (55) | 77 (58) |

| Child sex | ||

| Male | 70 (55) | 68 (50) |

| Child birthweight | ||

| Birthweight in kg (mean) (95% CI) | 3.1 (3.0–3.2) | 3.1 (3.0–3.2) |

- a Variables contributing to the risk measure. 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals.

Intervention effects

There was a trend for intervention group infants overall to have higher MDI scores than those of control group infants (F1,261=2.8, p=0.09, d=0.20). Means (and confidence intervals) were 85.2 (95% CI=83.4–87.1) and 83.1 (95% CI=81.3–84.8) respectively.

Level of socio-economic risk as a moderator of intervention effects

The six socio-economic risk factors showed a number of significant associations with one another (e.g. less education was associated with having other children [phi=0.19, p=0.002], unplanned pregnancy was associated with being an adolescent [phi=0.27, p=0.001] and lack of partner support [phi=0.22, p=0.001]). The six factors were therefore aggregated into a composite risk measure for each mother, which was then averaged; these continuous risk scores were then converted into a binary variable using a median split (median=0.7, interquartile range [IQR]=0.3) to specify groups at either higher or relatively lower risk. For the current sample with cognitive assessments, 106 mothers (40%) were in the higher risk group. There was no difference in the rates of high risk between intervention and control groups (42% and 39% respectively; χ2[1]=0.2, p=0.71).

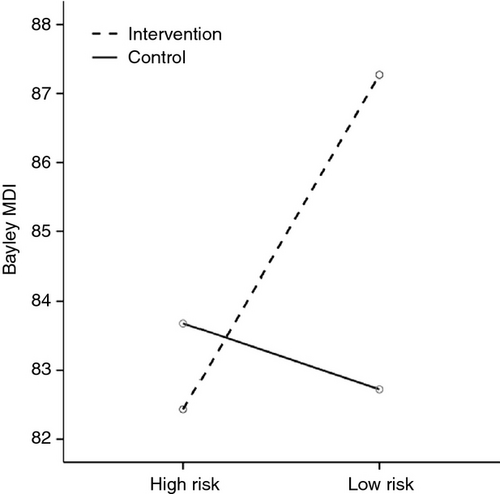

The effect of risk status on the Bayley MDI scores was not significant (p=0.17, d=0.17). Nevertheless, there was a significant interaction between risk and intervention (p=0.03,  =0.02): infants whose mothers had relatively lower socio-economic risk had significantly better MDI scores if their mothers received the intervention than the other groups of infants, the difference, on average, being 4.8 scale points (see Table 2a and Fig. 2). When the scores for the lower risk intervention group were compared with those for the three other groups combined, the effect size was d=0.41, and when compared to scores of only lower risk controls, d=0.42 (both small effects). When both level of risk and the above interaction effect were entered in the model, the effect of intervention was no longer marginally significant (F1,259=1.6, p=0.20,

=0.02): infants whose mothers had relatively lower socio-economic risk had significantly better MDI scores if their mothers received the intervention than the other groups of infants, the difference, on average, being 4.8 scale points (see Table 2a and Fig. 2). When the scores for the lower risk intervention group were compared with those for the three other groups combined, the effect size was d=0.41, and when compared to scores of only lower risk controls, d=0.42 (both small effects). When both level of risk and the above interaction effect were entered in the model, the effect of intervention was no longer marginally significant (F1,259=1.6, p=0.20,  =0.006), indicating that the benefit of intervention was carried by the group where mothers had lower risk.

=0.006), indicating that the benefit of intervention was carried by the group where mothers had lower risk.

| Intervention | Control | Risk effect | Interaction risk with intervention group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | SEadj (95% adjCI) | M (SD) | SEadj (95% adjCI) | |||

| (a) Risk composite | ||||||

| High risk | 82.4 (9.9) | 1.4 (79.5–85.3) | 83.7 (9.6) | 1.3 (80.9–86.4) |

F1,261=1.9 p=0.17, d=0.17 |

F1,259=5.0 p=0.03, |

| Low risk | 87.3 (11.2) | 1.3 (84.7–89.6) | 82.7 (10.2) | 1.1 (80.5–85.3) | ||

| (b) Individual risk factors | ||||||

| Adolescent mother | ||||||

| Adolescent | 88.3 (10.9) | 2.2 (83.6–92.9) | 82.9 (8.6) | 1.6 (79.6–86.0) |

F1,258=1.0 p=0.31, d=0.15 |

F1,256=1.5 p=0.22, |

| Not adolescent | 84.5 (10.8) | 1.1 (82.5–86.4) | 83.1 (10.3) | 1.0 (81.1–85.0) | ||

| Educated ≤6y | ||||||

| ≤6y | 84.5 (11.2) | 1.9 (80.9–88.2) | 82.8 (10.9) | 1.7 (79.7–86.0) |

F1,261=0.3 p=0.56, d=0.07 |

F1,259=0.04 p=0.84, |

| ≥7y | 85.5 (10.8) | 1.1 (83.6–87.7) | 83.2 (9.6) | 1.0 (81.5–85.2) | ||

| No partner support | ||||||

| No help | 83.4 (12.0) | 2.2 (79.0–87.6) | 84.6 (9.2) | 1.8 (80.9–88.2) |

F1,260=0.03 p=0.86, d=0.02 |

F1,258=2.1 p=0.14, |

| Some help | 85.9 (10.5) | 1.1 (84.0–88.0) | 82.7 (10.2) | 1.0 (80.8–84.6) | ||

| No electricity | ||||||

| No electricity | 81.4 (9.2) | 1.1 (79.2–83.6) | 83.1 (9.7) | 1.2 (80.9–85.2) |

F1,261=10.2 p=0.002, d=0.39 |

F1,259=11.8 p=0.001, |

| Electricity | 89.9 (10.9) | 1.5 (87.0–92.7) | 83.1 (10.3) | 1.3 (80.5–85.8) | ||

| Unplanned pregnancy | ||||||

| Unplanned | 83.9 (9.4) | 1.3 (81.3–86.2) | 84.7 (8.7) | 1.2 (82.3–87.4) |

F1,261=0.02 p=0.86, d=0.02 |

F1,259=3.4 p=0.06, |

| Planned | 86.2 (11.8) | 1.3 (83.5–88.6) | 82.2 (10.6) | 1.1 (80.2–84.2) | ||

| Not primiparous | ||||||

| Not primiparous | 83.7 (10.2) | 1.2 (81.3–86.2) | 82.9 (9.6) | 1.1 (80.8–85.1) |

F1,254=2.2 p=0.14, d=0.18 |

F1,252=2.3 p=0.13, |

| Primiparous | 87.5 (11.1) | 1.5 (84.3–90.6) | 82.8 (10.4) | 1.4 (79.9–85.9) | ||

- Bootstrapping with bias correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. SEadj, adjusted standard error; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals.

To investigate whether the moderating effect of overall risk status was carried by specific factors, the risk composite was disaggregated, and main and interaction (with intervention group) effects on the MDI were examined for each one. One significant main effect was observed, with infants whose mothers had electricity at home having significantly higher MDI scores than those of mothers without electricity (electricity M=86.3, 95% CI=84.5–88.1; no electricity M=82.2, 95% CI=80.5–83.9). Furthermore, examination of the interaction showed that the benefit to infant cognitive outcome of the intervention applied only to those having electricity in the home (see Table 2b).

Antenatal depression

Compared with infants with non-depressed mothers, those whose mothers were antenatally depressed had significantly lower MDI scores (F1,262=4.4, p=0.04, d=0.33; antenatally depressed: M=81.4, 95% CI=78.6–84.3; not antenatally depressed: M=84.8, 95% CI=83.4–86.2). This effect still held when depression at 2 months and 6 months was included as a covariate (p=0.03 and p=0.05 respectively.) Accordingly, we examined whether the effect on infant MDI of the intervention, in interaction with maternal risk status, was still significant having taken antenatal depression into account. As shown in Table 3, the effect of the interaction between group and risk was unchanged, while that of antenatal depression was somewhat reduced, although a trend effect remained. Antenatal depression was also examined as a potential moderator of the intervention effects; results did not show a significant antenatal depression*intervention group interaction (F1,259=1.0, p=0.32,  =004).

=004).

| F | p | n 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal depression | 3.1 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Intervention group | 1.5 | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| Risk status | 1.0 | 0.30 | 0.004 |

| Intervention group* risk status | 5.1 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

Infant sex

Infant sex had no effect on Bayley MDI scores, either alone (F1,259=0.7, p=0.41, d=0.13) or in interaction with maternal risk (F1,259=0.9, p=0.34,  =0.004). Similarly, infant sex did not significantly moderate the effects of intervention (F1,249=0.04, p=0.84,

=0.004). Similarly, infant sex did not significantly moderate the effects of intervention (F1,249=0.04, p=0.84,  =001).

=001).

Infant cognitive outcome and attachment

Our principal finding, that the beneficial effect of the intervention on infant cognitive performance was confined to families with a lower level of risk, raised the question of whether a similar relationship between intervention and risk also applied to infant attachment. This was not the case, with the effect of the interaction between intervention and risk on infant attachment being non-significant (Wald=0.03, df=1, OR=0.9 [95% CI 0.3–2.8], p>0.8). Indeed, there was no association between infant attachment security and cognitive outcome, with mean MDI scores for secure versus insecure infants being 83.9 and 84.7 respectively (p=0.56).

Discussion

In a socio-economically deprived peri-urban settlement in South Africa, a home-visiting intervention, delivered by community workers to mothers during pregnancy and the first 6 postpartum months had no overall effect on infant cognition at 18 months in contrast to its benefit to attachment. Nevertheless, for those not living in conditions of particularly high socio-economic risk (principally those in dwellings with electricity), the intervention was of benefit to infant cognitive development. In addition to intervention and socio-economic risk effects, infants whose mothers were antenatally depressed tended to have lower cognitive scores.

A number of aspects of our intervention require comment. First, with regard to the overall lack of benefit of our intervention on infant cognitive development, it is important to bear in mind that the intervention was focused on providing the mother with psychological support and help in her attachment relationship with her infant (i.e. supporting the management of infant distress, and sensitizing mothers to infant social cues and attachment needs). Although some of the parenting qualities that help promote secure attachment are also relevant to child cognitive development (e.g. general responsiveness), other parenting practices were absent from our intervention that are known to be of specific benefit to child cognitive functioning. These are guided learning, verbal stimulation, and the ‘scaffolding’ of infant attention and engagement with the environment. Thus, a more cognitively focused intervention than ours, with clearer didactic elements and encouragement to parents to practise, may have produced greater cognitive gains for the infants.

A second possible barrier to the effectiveness of our intervention, aside from its attachment versus cognitive focus, was infant age. It is possible that parenting support for infant cognitive development is more effective when infants are older than those in our intervention (i.e. >6mo), when infant attention and motor skills have developed sufficiently to enable active engagement with the wider environment, and provide more opportunities for parents to facilitate infant cognitive skills. Indeed, successful interventions for infant cognitive development in low- and middle-income countries have generally provided support for children up to 1 to 3 years of age.12, 13, 23

A further aspect of our findings requiring comment is that the failure of the intervention to benefit infant cognitive development applied principally to infants of mothers experiencing particularly high levels of socio-economic risk. This may have been because of factors on either the mothers’ or the infants’ part. Thus, the extremes of adversity facing these mothers may have prevented them from engaging effectively with the intervention. Similarly, there may have been unmeasured effects of higher risk on the infants of these mothers, such as nutritional deficiencies or recurrent infections (e.g. respiratory and gastrointestinal), that may have meant they could not benefit cognitively from the intervention. In either case, and in line with other studies,11, 13 our results suggest that those in particularly adverse circumstances may need to receive broader support (e.g. economic or nutritional) if child cognitive development is to improve in the context of home-visiting.

Finally, consistent with reports from high-income countries,17 our findings suggest that it may be useful to focus on antenatal and postnatal maternal depression. Encouragingly, recent programmes show that screening for depression in pregnancy can be successfully integrated into primary level maternity services in low- and middle-income countries,24 and lay community workers can be trained to deliver support that is effective in reducing depression.25 Future research would benefit, therefore, from assessing whether interventions for antenatal depression can improve infant cognitive functioning.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Wellcome Trust (B574100) and the Vlotman Trust. We thank Mireille Landman for provision of clinical supervision; Marjorie Feni, Nomabili Siko, Nokwanda Sikana, and Lephina Makhanya, the community workers in this study; Nosisana Nama, Busisiwe Magaze, and Amy Matheson who assisted in the assessment of the mothers and infants; Leonardo De Pascalis who advised on statistical analyses; and Leslie Swartz and Chris Molteno who contributed to the original planning of the study. We are particularly grateful to the families from Khayelitsha who participated in this research. MT is supported by the National Research Foundation, South Africa. The authors have stated that they had no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

=0.02

=0.02 =0.006

=0.006 =0.001

=0.001 =0.008

=0.008 =0.04

=0.04 =0.01

=0.01 =0.009

=0.009