Recent innovations in therapeutic endoscopy for pancreatobiliary diseases

Abstract

The development of endoscopic treatment for pancreatobiliary diseases in recent years is remarkable. In addition to conventional transpapillary treatments under endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), new endoscopic ultrasound-guided therapy is being developed and implemented. On the other hand, due to the development/improvement of various devices such as new metal stents, a new therapeutic strategy under ERCP is also advocated. The present review focuses on recent advances in the endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts, walled-off necrosis, malignant biliary strictures, and benign biliary/pancreatic duct strictures.

Introduction

In recent years, the development of new endoscopes and associated devices has led to various ideas regarding and the practical application of new endoscopic treatment techniques. For the treatment of pancreatobiliary diseases, in addition to transpapillary endoscopic treatment methods that were previously used, there has been a rapid development of transgastrointestinal treatment methods using endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS); EUS has been used to treat various benign and malignant pancreatobiliary conditions. Dramatic progress has been recently made in the endoscopic treatment of benign biliary and pancreatic duct strictures, and the indications for endoscopic treatment have markedly increased.

The present review focuses on advances in the endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts (PPCs), walled-off necrosis (WON), malignant biliary strictures, and benign biliary and pancreatic duct strictures.

Progress of EUS-guided Therapy for Pancreatobiliary Diseases

Advances in EUS had greatly changed pancreatobiliary endoscopy, which was used only for observation until 1992, when Vilmann et al.1 were the first to use EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy clinically; since then, the use of interventional EUS has increased rapidly.2 At present, interventional EUS is mostly used for drainage of pancreatic fluid collection,3 bile duct,4 gallbladder,5 and pancreatic duct.6 Among the above drainage methods, the one that has spread most rapidly is the drainage of WON. In cases of WON that cannot be alleviated by drainage alone, endoscopic necrosectomy via a fistula is useful.

Regarding EUS-guided bile duct drainage (EUS-BD), EUS was previously used mainly for bile duct drainage in malignant diseases, but it has recently also been applied for treating benign conditions, such as calculus removal via a fistula and eliminating bile duct and gastrointestinal anastomoses. EUS-guided pancreatic duct drainage (EUS-PD) is the most challenging drainage technique, because of its practical difficulty and because of no alternative methods. In the future, EUS devices may be further developed, and this technique will be established, for additional indications, as well as current ones.

Endoscopic Therapy for Pancreatic Pseudocyst/Walled-off Necrosis

Endoscopic ultrasonography-GUIDED DRAINAGE is the first-line treatment for infected PPCs and WON according to the revised Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis.7 In particular, the mortality rate with infected WON is high, at approximately 20%, and intervention is recommended if the general condition deteriorates despite administration of antibacterial agents. Initially, the treatment was mainly by implantation of multiple double-pig-tail stents, and the results were reported to be mostly favorable, with a technique completion rate of approximately 95%, a cure rate of approximately 90%, and a procedural accident rate of approximately 11%.8, 9, 3 Recently, a dumbbell-shaped, lumen-apposing fully covered self-expanding metal stent (LAMS) was developed, once this type of stent has been implanted, the probability of it being dislodged is extremely low, and an endoscope can easily be inserted into the WON via the stent lumen, so high safety, and therapeutic efficacy are expected.10

Siddiqui et al.11 have compared the therapeutic efficacy, long-term prognosis, and safety of various types of stent [double-pigtail plastic stent (DP), fully covered self-expanding metal stent (FCSEMS), and LAMS] used for EUS-guided drainage in 313 WON patients, and the final therapeutic success rates were as follows: DP group: 81% (86 of 106); FCSEMS group: 95% (115 of 121); and LAMS group: 90% (77 of 86). The rate in the DP group was thus significantly lower (P = 0.0001). Besides, the number of treatments needed for elimination of the WON was significantly lower in the LAMS group than in the DP and FCSEMS groups, at 2.2, 3.0, and 3.6, respectively (P = 0.04). Furthermore, the rate of early adverse events (AEs) was significantly lower in the FCSEMS group than the DP and LAMS groups; and the rate of delayed AEs was significantly lower in the LAMS group than the DP and FCSEMS groups. Chen et al.12 similarly found that groups in which plastic stents and LAMSs were used for treating WON showed no difference in the AEs rate, but the clinical success rate was significantly higher in the group in which LAMSs were used. In addition, Yang et al.13 evaluated delayed AEs when drainage using LAMSs was performed with WON and PPCs and found that stent occlusion in 18 (29.5%) and 10 (17.5%) patients, respectively, with no cases of delayed bleeding or buried stent being found by follow-up endoscopy. On the other hand, Bang et al. performed comparative studies of LAMS and plastic stent implantation, and reported there was no difference in clinical outcomes.14, 15 In their latest report, in the LAMS group, the procedure duration was shorter (15 vs. 40 min; P < 0.001), the frequency of stent-related AEs was higher (32.3% vs. 6.9%; P = 0.01), and the cost of the procedure was higher (US$ 12 155 vs. US$ 6609; P < 0.001). It was concluded that except for the procedure duration, there was no significant difference in treatment outcomes between LAMSs and plastic stents. Thus, LAMS is considered to be a highly useful stent. Nevertheless, further research is needed.16

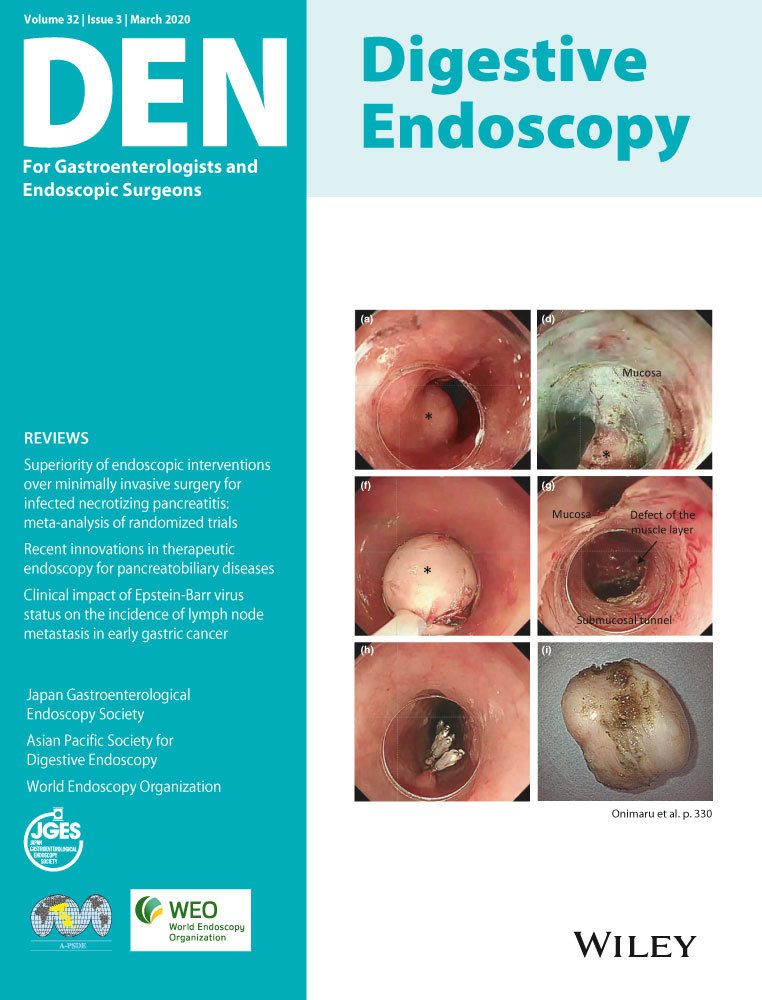

In contrast, there are some patients for whom drainage alone does not provide a satisfactory outcome, and in these patients, direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) is performed. Multicenter studies conducted in Japan, Germany, and USA17-19 reported that therapeutic success rates were satisfactory (75%, 80%, and 91.3%, respectively), whereas incidence rates of complications (14–33%) and mortality rates (6.7–11%) were high in all three studies. In light of these findings, the step-up approach is recommended for endoscopic therapy for WON. However, Yan et al.20 performed a multicenter retrospective study to compare the clinical outcomes and predictors of success for endoscopic drainage of WON with LAMS followed by immediate or delayed DEN performed at standard intervals and concluded that DEN at the time of initial stent placement reduces the number of DEN sessions required for successful clinical resolution of WON. Several studies on endoscopic treatment for WON and PPCs have thus been conducted, but it cannot be said that a standard therapeutic strategy has been established, and further research is needed.

Endoscopic Therapy for Malignant Biliary Strictures

Endoscopic biliary drainage first started with endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, as reported by Nagai et al. in 1976.21 Endoscopic biliary stenting with plastic stents was then reported by Soehendra et al. in 1980.22 SEMSs have only been previously used for nonresectable, malignant biliary strictures, but endoscopically removable CSEMS have become commercially available recently.

Regarding nonresectable malignant hilar biliary strictures (MHBS), in bilateral drainage using multiple metal stents, no conclusion has been reached as to whether side-by-side (SBS) or partial stent-in-stent positioning is preferable.23-25 In addition, it is still debated whether PS or SEMS is better. Gao et al.26 demonstrated no significant difference in clinical success and early/delay AE between plastic stent and SEMS in patient with unresectable gallbladder cancer with hilar biliary obstruction. Recently, SEMS with small diameters has become available. Kitamura et al.27 have reported that endoscopic SBS placement of the partially CSEMS was feasible in patients with unresectable MHBS, and also that re-interventional stent removal was possible in the absence of tumor ingrowth. Inoue et al.28 have reported that simultaneous SBS placement using the novel 5.7-Fr SEMS delivery system may be more straightforward and have a higher success rate than sequential SBS placement. Recently, EUS-BD for patients in whom the transpapillary approach is difficult is widely performed.29 Three randomized controlled trials that compared EUS-BD with transpapillary-BD indicated that the success rate of both techniques is similar, but AEs and reintervention rates might be lower for EUS-BD.30-32 The newest systematic review and meta-analysis also showed the same results.33

For preoperative biliary drainage, PSs are generally used. However, the surgery duration is higher in patients in whom preoperative chemotherapy is used to treat borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Tol et al.34 demonstrated that FCSEMSs yield a better outcome than PSs with preoperative biliary drainage in pancreatic cancer patients.

In recent years, there have been reports on the successful use of endoscopic biliary radiofrequency ablation for treating unresectable malignant biliary strictures. In a meta-analysis of 263 patients in the nine reports published to date,35 it was found that the stricture diameter increased significantly after endoscopic biliary radiofrequency ablation, and the pooled rate of AEs was 17%. This procedure may be effective and generally safe and may improve overall survival.

Endoscopic Therapy for Benign Biliary Stricture

In recent years, several studies have been conducted on endoscopic treatment of benign biliary strictures. In general, multiple plastic stent implantation is recommended for treating benign biliary strictures,36 and the number of reports on FCSEMS implantation has recently increased. Zheng et al.37 performed systematic review and meta-analysis, reported that placement of CSEMS was effective in the treatment of benign biliary stricture with relatively short stenting duration and low long-term stricture recurrence rate. Martins et al.38 compared CSEMS and multiple PSs, with 64 patients in each group, for treating biliary anastomotic strictures after liver transplantation. They found that, although the technical success rate was 100% in both groups, and there was no significant difference in clinical success rate, at 83.3% and 96.5%. The following problems occurred at significantly higher in the FCSEMS group: restenosis: 32% vs. 0%; AEs: 23.3% vs. 6.4%; and acute pancreatitis: 13.3% vs. 2.1%. Other studies39-41 showed that CSEMSs resulted in approximately the same stricture elimination rate as PSs, but involved fewer surgical procedures. In addition, in the most recent meta-analysis,42 when the multiple PSs group and the CSEMS group were compared, no significant differences were found in stricture elimination, restenosis, and AEs rate. On the other, the use of CSEMSs was advantageous from an economic point of view. Similar findings have been reported in other meta-analyses.43-46

Regarding the biliary strictures associated with chronic pancreatitis (CP),47 although a comparison of the multiple PSs and CSEMS showed no significant difference in the clinical response rate at 1 year after treatment (33% vs. 77%; P = 0.06), the delayed AEs rate and number of reinterventions were significantly lower in the CSEMS. According to Haapamäki et al.,48 the treatment success rates after 2 years were approximately the same as those in the multiple PSs and CSEMS (90% vs. 92%). One factor that predicts a long stent-free period after stent removal was a pre-treatment stricture length of <24 mm.49 Although stent migration is a concern, involving changing the shape of the FCSEMS,50-52 the use of CSEMSs may become the mainstream treatment for benign biliary strictures in the future.

Recently, EUS-BD for benign biliary strictures is considered to be available. Mukai et al.53 recently used EUS-guided antegrade intervention for 37 patients with postoperative biliary tract disease, including 21 patients with anastomotic strictures, and the success rate was 91.9%, with the AEs rate being 8.1%. Taking this finding together with those in other reports,54, 55 it can be seen that EUS-BD is a safe alternative treatment method for patients in whom ERCP is unsuccessful.

Moreover, as a treatment method specifically for benign biliary strictures, attempts to use magnetic compression anastomosis have been made for some time. However, Jang et al.56 recently reported a study in which recanalization was successfully achieved in 89.7% of patients (35 of 39), no major AEs occurred, the mean time from magnet approximation to removal was 57.4 days, and the mean follow-up period after recanalization was 41.9 months. This treatment method may develop further in the future.

Endoscopic Therapy for Benign Pancreatic Ductal Stricture

The main cause of benign pancreatic duct stenosis is CP. CP is a progressive inflammatory disease of the pancreas that is characterized by destruction of the pancreatic parenchyma with subsequent fibrosis that leads to pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. Severe abdominal pain and local complications, such as pseudocyst formation, caused by pancreatic ductal stenosis and/or pancreatic stones secondary to CP are indications for drainage therapy using endoscopy.57 Such drainage is usually performed by transpapillary endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy, dilation, and stenting as the first-line treatment. However, for patients in whom such transpapillary drainage due to postsurgical anatomy and/or refractory ductal stenosis is difficult, transmural drainage under EUS guidance can be performed with the advancement of devices and echoendoscope.58 Nowadays, the development of EUS-guided pancreatic duct intervention plays an important role as an alternative to surgical intervention.

In CP patients, due to the recurrence of the stricture after definitive stent removal, the patient is forced to undergo routine stent replacement. In 2006, Costamagna et al.59 demonstrated that multiple pancreatic stenting is promising in obtaining persistent stricture dilation on long-term follow-up in the setting of severe CP. Although Park et al.60 reported the feasibility and safety of an FCSEMS placement, in the systematic review61 on the effects of FCSEMS and multiple PSs for benign pancreatic duct stenosis written in 2014, there was no difference between the two groups regarding the efficacy and safety. However, recently, there have been several reports regarding the good results in long-term follow-up of the placement of FCSEMS. Oh et al.62 reported that stents could easily be removed at a median of 7.5 months after their insertion in all cases without migration during placement, and 13 (86.7%) of the 15 patients who had responded to pancreatic stenting maintained the response during follow-up (median of 47.3 months) after definite stent removal. Tringali et al.63 showed that FCSEMS removability from the painful pancreatic duct was feasible in all cases, and 90% of the patients were asymptomatic after 3 years. In addition, Cahen et al.64 demonstrated the effectiveness of the biodegradable self-expandable stents for fibrotic pancreatic duct stricture. They performed the procedure in 19 patients, and the stricture resolution was accomplished in 11 patients (technical success rate 58%, clinical success rate 52%) with no major AEs.

On the other hand, EUS-guided transmural approaches for the cases in which transpapillary approach is difficult/failed have been recently in the limelight.65, 66 EUS-PD are divided into two categories: EUS-guided antegrade drainage and EUS-guided rendezvous technique. EUS-guided antegrade drainage is performed by accessing the main pancreatic duct under EUS-guided puncture and creating a tract with subsequent antegrade placement of a stent across the pancreatic-gastric anastomosis and pancreatic-duodenal anastomosis. EUS-guided rendezvous achieves transpapillary or trans-anastomotic drainage using a rendezvous technique. This is achieved by retrograde stent placement from the papilla or anastomosis into the painful pancreatic duct via another endoscope. Since this procedure is complicated, antegrade drainage has been mainly performed to date. Tyberg et al.67 performed a multicenter international collaborative study regarding antegrade drainage and analyzed in 80 patients. The technical success was achieved in 89% of patients, and clinical success was achieved in 92% of patients who achieved technical success without major AEs. Itoi et al.68 made a unique specialized plastic stent for EUS-PD (an effective length of 15 cm, four flanges; two in the distal end and two at the proximal end, pigtail shape in proximal end) and they demonstrated69 good technical and clinical success rate in short/long-term follow-up period (range, 6–44 months) with no major AEs.

Conclusion

Dramatic progress with endoscopic treatment for pancreatobiliary diseases has been made in recent years, and it is hoped that this will continue in the future. However, increased complexity and sophistication of techniques result in an increased risk. Important factors requested by endoscopists include education regarding advances that have been made in endoscopic treatment and risk management appropriate to the current situation in medical ethics.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.