Diagnosis of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps using endocytoscopy (with videos)

Abstract

Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/P) are considered to be precursors of colorectal cancers. They therefore need to be distinguished from hyperplastic polyps, and should be treated similarly to adenomas. Various endoscopic classifications for discriminating SSA/P have recently been proposed and validated, including the ‘Type II-O’ pit pattern in magnifying chromoendoscopy and the ‘varicose microvascular vessel’ in narrow-band imaging. However, there is currently no diagnostic consensus on the endoscopic appearance of SSA/P. Endocytoscopy (EC) is an emerging modality with diagnostic potential for SSA/P. EC is a type of a contact light microscopy, which allows in vivo visualization of cells and nuclei facilitating precise, real-time pathological prediction. SSA/P show oval gland lumens with small round nuclei in EC, indirectly reflecting the pathological features. EC has shown a sensitivity of 83.3% and a specificity of 97.8% for the diagnosis of SSA/P. EC is also a promising tool for the diagnosis of SSA/P with cytological dysplasia because of its ability to detect morphological changes in nuclei, which is the most important factor determining the presence of dysplasia in the lesion. However, clinical data validating the usefulness of EC are lacking, and further studies are required.

Introduction

Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/P) are sessile polyps usually found in the right side of the colon. SSA/P have recently received attention because of their malignant potential associated with high microsatellite instability, suggesting that they should be managed clinically in a similar fashion to adenomatous polyps.1 Hyperplastic polyps (HP) have similar macroscopic forms to SSA/P but lack malignant potential, and can therefore be left in situ without resection. It is therefore essential to distinguish SSA/P from HP.

It has previously been considered difficult to differentiate between SSA/P and HP endoscopically,2 but recent research has revealed potential for the endoscopic diagnosis of SSA/P.3-9 Some studies have focused on the macroscopic appearance of the lesions, including a mucus cap, rim of debris, and bubbles,6 whereas others have investigated their features as revealed by narrow-band imaging, such as a cloud-like surface and dark spots, or by magnifying endoscopy, demonstrating improved diagnostic accuracies.3, 5, 7, 9 Among these identifying features, a novel ‘Type II open-shape pit pattern’ (Type II-O)7 has become widely accepted and used in clinical practice in Japan. Type II-O is a useful indicator of SSA/P because it indirectly reflects dilation of the gland ducts, and demonstrates excellent specificity of 97.3%. However, reproducibility of the classification Type II-O is unknown.

In the present review, we focus on the optical diagnosis of SSA/P using the recently developed form of ultra-magnifying endoscopy, endocytoscopy (EC). EC has the potential to visualize gland lumens and nuclei in the target lesion directly, and may thus provide a more reliable diagnostic modality for SSA/P compared with other emerging endoscopic classifications.

Endocytoscopy

Endocytoscopy involves a contact light microscopy system integrated into the distal tip of a conventional colonoscope (Fig. 1). It is a novel emerging endoscopic system, with a prototype provided by Olympus Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). In contrast to other modalities, the ultra-magnification capability of EC enables in situ observation not only of structural atypia (e.g. gland lumens), but also of cytological atypia (e.g. nuclei). EC has demonstrated good consistency in assessing the histopathology of lesions in the alimentary tract,10-15 and is thus expected to provide the next-generation technique for optical biopsy.

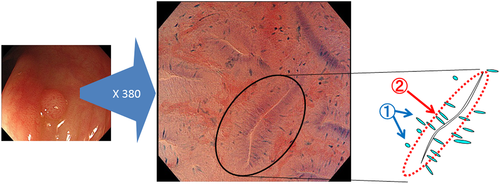

EC (CF Y-0020; Olympus Corporation) has two separate observation modes: standard video endoscopy and EC (ultra-magnifying mode). Using a hand lever, endoscopists can carry out consecutive EC observations as well as standard video endoscopy, without changing the scope. EC observation is based on the principles of contact light microscopy, and the CF Y-0020 has 380-fold magnification with a focusing depth of 50 μm and field of view of 700 × 600 μm. EC images contain morphological information on gland duct lumens and the shape of the nuclei in the epithelial superficial layer, which can provide good clues for pathological prediction (Fig. 2).

Prior dye staining is required to obtain EC images. The recommended solution contains 1.0% methylene blue to stain the nuclei, and 0.05% crystal violet to stain the cytoplasm.16, 17 This double-staining regimen ensures good contrast of the nuclei and provides high-quality EC images similar to conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining in pathological specimens. However, staining takes approximately 1 min prior to observation, which can be one drawback of EC.

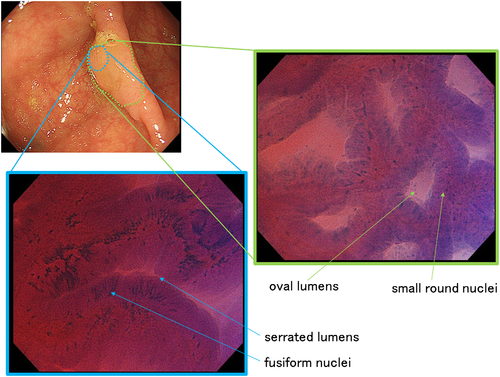

The diagnostic process using EC for adenoma is shown in Figure 2. Diagnosis is based on the appearance of two structures in the EC image, the nuclei and the lumens. In Figure 2, the nuclei are swollen and fusiform whereas the lumens are slit-like, which constitutes a characteristic appearance of adenomas in EC images. This diagnostic process is similar to histopathological diagnosis, which focuses on both cytological atypia (e.g. nuclei) and structural atypia (e.g. formation of gland ducts corresponding to lumens in the EC image). This similarity contributes to the good diagnostic performance of EC. Previous studies on the diagnostic ability of EC10, 12, 18-20 have reported accuracies of 96.0–100% for detecting neoplastic change, and 91.2–98.3% for detecting deeply invasive submucosal cancer. EC also demonstrated excellent reproducibility, with interobserver agreement of 0.62–0.829 and intraobserver agreement of 0.80–0.899.

Endocytoscopic Diagnosis of SSA/P and HP

In 2014, Kutsukawa et al. reported the usefulness of EC for the classification of serrated polyps21 in a retrospective analysis of 58 cases. Serrated polyps could be clearly classified into SSA/P, HP, and traditional serrated adenomas (TSA) according to their EC findings. SSA/P were characterized by the presence of oval lumens, HP by the presence of star-like lumens, and TSA by the presence of fusiform nuclei and villous and serrated lumens. This classification system focusing on the form of the lumens allows SSA/P to be discriminated from other serrated polyps with a sensitivity of 83.3% and a specificity of 97.8%.

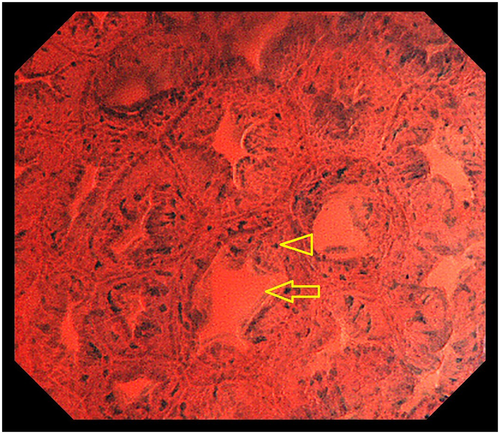

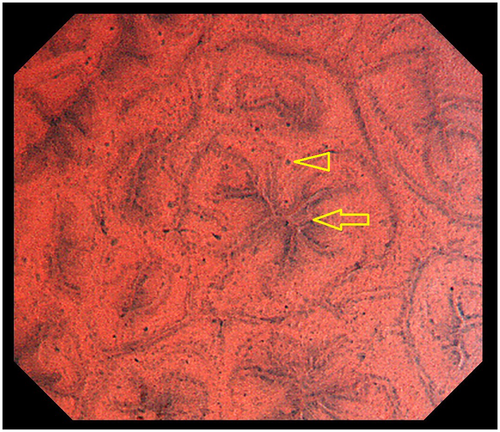

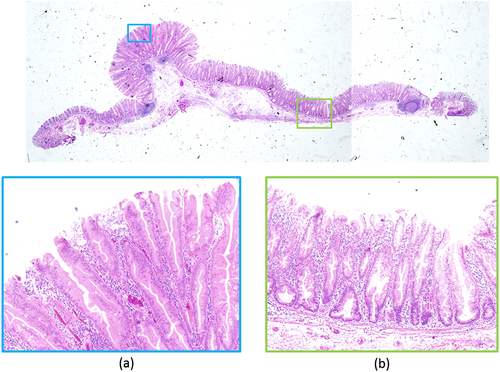

Typical cases of SSA/P and HP are shown in Figures 3, 4. An SSA/P (Fig. 3) demonstrates oval lumens and small, round nuclei, whereas a HP (Fig. 4) reveals star-like lumens and small, round nuclei. This difference between lumen architecture in EC images of SSA/P and HP indirectly reflects their different pathological structures. In pathological specimens, SSA/P have crypts which are often dilated and show abnormal shapes, including L-shaped and inverted-T-shaped, whereas HP have elongated crypts with variable degrees of serration and narrow bases.2, 22 These pathological features are considered to correspond to the oval and star-shaped lumens demonstrated by EC.

The EC differences between SSA/P and HP are demonstrated in the attached videos (Videos S1 and S2), which clearly show larger lumens in SSA/P (Video S1) compared with HP (Video S2). The dilated oval lumens characteristic of SSA/P in EC images are considered to correspond to Type II-O7 in magnifying chromoendoscopy. However, EC has the potential to evaluate lumen area more objectively than magnifying endoscopy because of its fixed magnification power of 380, compared with the magnification power of normal magnifying endoscopy, which varies depending on the situation and the individual endoscopist. Studies are currently underway to measure the luminal area of the serrated lesions using a computer-aided diagnosis system15 to allow more precise and objective discrimination between SSA/P and HP.

Diagnosis of SSA/P by EC imaging has one major limitation; histogenesis of SSA/P is considered as bottom-up type. Therefore, usefulness of EC diagnoses for SSA/P is limited to lesions in which dilated gland ducts occupy all layers of mucosa. In addition, cytological characteristics of SSA/P on mucosal surface in EC imaging has not yet been clarified; thus further research on this issue is much needed.

Diagnosis of SSA/P Using Probe-Based Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy

Probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy (pCLE) uses an ultra-magnifying endoscope and can carry out an optical biopsy similar to EC. However, in contrast to EC, few reports have evaluated the diagnostic usefulness of pCLE for SSA/P. A review by Moussata et al. reported that crypt architecture was modified and dilated by the accumulation of mucus, which appeared black in endomicroscopic images, whereas the lumen was enlarged and stellar in shape, as in histological specimens. They suggested that it was easier in practice to recognize SSA than HP using endomicroscopy,23 but they did not provide any detailed explanation or statistical data.

Case Report

Figure 5 shows an SSA/P with cytological dysplasia, located in the cecum. The lesion was 20 mm in diameter and its macroscopic form was IIa (Paris classification24). The surface of the lesion was covered with mucus, but after removal of the mucus by flushing with water, a slightly protruding component was detected on the left side of the lesion. EC observation showed two different images: EC images of most of the component revealed oval lumens with small nuclei characteristics of SSA/P, whereas EC images of the slightly protruded area showed serrated lumens with fusiform nuclei, characteristic of TSA.

Histopathological examination (Fig. 6) demonstrated similar findings to EC observations. There was a small nodule within a slightly elevated area; the slightly elevated area was pathologically characteristic of SSA/P (Fig. 6b), whereas the small nodule contained a dysplastic component resembling TSA (Fig. 6a). The lesion was therefore diagnosed as SSA/P with cytological dysplasia. In this case, EC was useful for predicting the dysplastic area in SSA/P. Although there have been few reports regarding the endoscopic characterization of SSA/P with cytological dysplasia, EC could be a promising tool for this purpose.

Conclusions

There is currently no consensus regarding the endoscopic diagnosis of SSA/P, although emerging endoscopic modalities offer attractive diagnostic possibilities, including the Type II-O pit pattern in magnifying chromoendoscopy and the varicose microvascular vessel in narrow-band imaging. However, EC is the only form of endoscopy able to evaluate gland luminal area precisely and objectively together with information on cellular atypia, and thus has the potential to play an important role in the diagnosis of SSA/P. Further studies are needed to evaluate the usefulness of EC for the diagnosis of SSA/P in clinical practice.

Acknowledgment

We express our gratitude to Olympus Corporation for their invaluable support for the present study.

Conflict of Interests

HI: Olympus Corporation (lecture fee). The other authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.