Complete spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma (1986–2016): a 30 year perspective

The index case

In 1986, O Rourke and Bell, in Queensland Australia, described the first case of complete spontaneous regression (CSR) of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).1 At that time, the tumor was a relatively new entity, having first emerged in the medical literature in 1972 under the title ‘trabecular carcinoma of the skin’.2 Subsequently it came to be recognized as an aggressive primary cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma for which wide local excision, selective lymphadenectomy and loco-regional radiotherapy now serve as the mainstay of treatment.3, 4 The Australian authors' case was of a stereotypical MCC on the cheek of a 90-year-old Australian woman of Irish ancestry. Conservative treatment by simple local excision, mandated by the patient's advanced age and mental compromise, set the stage for events to follow. Local recurrence of the tumor and cutaneous metastases developed within a year of presentation. In the absence of therapeutic intervention, and to the great surprise of her caregivers, all of the lesions resolved spontaneously within 3 months of their appearance. The patient remained free of MCC until her death of other causes 18 months later.5 This case served as the prototype for examples of CSR of MCC to follow. In drawing parallels with other skin cancers known to regress spontaneously the authors invoked cellular immunity as the likely mechanism of regression, although their own microscopic evaluation had not disclosed evidence to support this hypothesis.

The clinical prototype

Since the seminal report by O' Rourke and Bell in 1986, less than 40 cases of regression of MCC have been published in the North American, Japanese and European literature.6-34 Mid-way through the ensuing 30 years, Connelly and colleagues conducted a helpful review of the topic.5 The authors recorded details of the 10 previously published cases of CSR of MCC and provided updated follow-up information on them. In so doing, they observed strict criteria for CSR, defined as ‘the complete disappearance of clinically evident tumor for the full extent of the follow-up period’. Some earlier reports were excluded because the regression was not considered unequivocally complete and/or spontaneous.

The review by Connelly et al. was based on the cases of 6 women and 4 men, ranging in age from 65–90 (mean 79) years. All primary MCCs, bar one, arose on the head or neck. CSR typically occurred following a diagnostic biopsy before standard treatment (a) could be initiated, (b) when it was declined by the patient or (c) when it was considered inappropriate in the context of extreme frailty or ill health. In all cases, CSR of the primary tumor, locally recurrent tumor, and/or metastasis to the skin or lymph nodes occurred within 18 months of diagnosis and in 6, within 4 months. The process, when it occurred, was described as ‘swift and dramatic’, with clinical resolution of all disease in a period of 1–3 months. During follow-up periods ranging from 13 months to 15 years after presentation, all patients remained free of MCC. Based on this review, the authors made some insightful conclusions. First, they noted that CSR of MCC was a valid entity, with an estimated incidence of 1.67% of reported cases of MCC. Second, they deduced that, were it not for deterrents to standard therapy in a frail elderly population, remission of the disease would have been attributed to successful treatment and the phenomenon of CSR would have gone undetected. Finally, they encouraged systematic study of such rare cases as potential keys to effective anti-cancer immunotherapy.

In the years following Connelly's review additional reports and further helpful overviews of CSR of MCC were published.15-17, 19-21, 25-27, 29, 34 These cases mirrored the established clinical paradigm. They included 10 women and 2 men, aged 67–94 (mean 82) years in whom the primary MCCs had mainly occurred on the head or neck (10 cases) and standard treatment had been deterred by coincidental health issues or patient preference. In most instances regression of the primary tumor followed a diagnostic biopsy or incomplete excision. In a few cases locally recurrent disease and/or nodal metastasis regressed spontaneously. Timelines for CSR were similar to those recorded earlier, often with disappearance of all clinical disease within 3 months of presentation.

Exceptions to the rule

Some reports of regression of MCC deviate from the stereotype. For instance, in a few cases it is doubtful whether regression was complete. As an example, a Japanese woman experienced spontaneous regression of a primary MCC on the cheek and cervical nodal metastasis.18 Follow-up 17 months after the onset of regression revealed cervical and mediastinal lymphadenopathy of undetermined cause, raising the possibility of persistent MCC. Another report documented episodic regression and recurrence of metastatic MCC originating from a primary tumor on the foot of a 58-year-old woman, again differing from the prototypic model of CSR.33

Questions have also arisen concerning the spontaneous nature of the regression in certain cases. An 87-year-old woman with a locally recurrent MCC on the forehead, cervical nodal disease and a lung lesion was considered inoperable. She was treated with a somatostatin analog, lanreotide 15 mg intramuscularly every 2 weeks.28 After 2 months of treatment, the tumor at the primary site and in the cervical lymph nodes had disappeared. Five months later there was recurrent MCC in a cervical lymph node. This was excised and the lanreotide was stopped. A subsequent evaluation 10 months later revealed no evidence of disease, apart from persistence of the lung lesion, the cause of which had never been established. Somatostatin analogs have been used in palliative settings to block the secretory effects of neuroendocrine tumors and provide symptomatic relief. They also have antiproliferative effects that may have influenced regression in this case of MCC. In a similar vein, a 58-year-old man with an unusual cytokeratin-7 positive MCC on the neck was treated in a standard manner by wide local excision, regional lymphadenectomy and post-operative radiotherapy.31 Six months after completion of therapy a nodule, which proved to be metastatic MCC, was demonstrated in his liver. Declining chemotherapy, the patient opted for alternative treatment including ‘somato-emotional-release’ therapy and dietary supplementation. Five weeks after commencing this regime the liver nodule disappeared and he remained disease free for almost 3 years of follow-up. It is unclear whether the strategies employed in these cases influenced resolution of the tumors.

Other cases of regression of MCC deviated from the standard in different ways. In one instance a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia was diagnosed simultaneously with an MCC on the forearm of a 70-year-old man.23 The tumor regressed spontaneously 3 weeks after a diagnostic fine needle aspirate. The paradox of effective antitumor immunity in a setting typically associated with immune compromise is remarkable. In another report, complete spontaneous regression of extensive metastatic nodal MCC in the pelvis and chest of a 60-year-old woman followed her presentation with nodal disease in the right groin.24 A primary cutaneous site of this tumor was never found. The phenomenon of ‘primary nodal Merkel cell carcinoma’, (PNMCC) reported in 14% of cases in one series,35 is enigmatic. Some have speculated that it is due to regression of the primary MCC but there are suggestions to the contrary. For instance, PNMCC is reported to pursue a less aggressive biological course than its cutaneous counterpart with nodal involvement36 and it is associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus only in a minority of cases.37 Alternative pathways to explain the phenomenon would be a primary origin from nodal cells (epithelial cell rests or native nodal stem cells), or a derivation from a primary tumor of the skin (or other site) with phenotypic versatility, or a combined phenotype in which the neuroendocrine component had remained incognito. The latter is, perhaps, more plausible than the concept of ‘disappearance without trace’ of a primary cutaneous MCC through regression.

Finally, a remarkable case of regression of an advanced MCC which occupied more than half of the patient's face deserves mention.30 Beginning as a nodule on the left lower eyelid of a 71-year-old man, the tumor was treated with a standard aggressive approach including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Regardless, it progressed inexorably causing marked disfigurement. Four months after cessation of chemotherapy, when all therapeutic options had been exhausted, regression of the tumor commenced. This was complete within 3 months and the patient remained disease free in the subsequent 2 years of follow-up.

Pathology

The ‘small blue round cell’ cutaneous tumor that we have come to recognize as MCC, by virtue of its morphology and characteristic immunohistochemical profile, is sometimes associated with a lymphocytic infiltrate. Dating back to the original case of CSR of MCC in 1986, cellular immunity was invoked as the mechanism of tumor regression and the same theme has prevailed in subsequent publications. Some have also implicated apoptosis of neoplastic cells as part of the regressive response.15, 18 Interestingly, only about half of the reports of CSR in the literature have documented the presence of a lymphocytic infiltrate in association with the primary tumor, although sampling of tumor sites following regression did reveal replacement of the neoplasm by lymphohistiocytic infiltrates and fibrosis.15, 33

In an interesting study from Japan in 2000,14 the authors studied factors that could potentially influence tumor biology in four MCCs which had undergone CSR and in three which had not. These included tumor cell characteristics such as (a) apoptosis (by the TUNEL index), (b) proliferative rate (by the proliferating cell nuclear antigen), (c) expression of the anti-apoptotic bcl-2 protein and (d) expression of the pro-apoptotic p53. They also studied the numbers of lymphocytes associated with the tumors. Of these parameters, only apoptosis and the number of tumor- infiltrating T lymphocytes proved to be significantly higher in the CSR group.

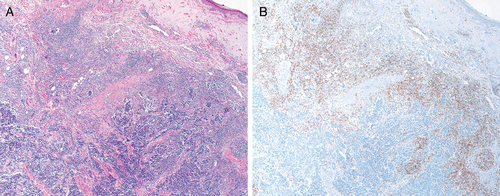

Recent studies have reinforced the favorable prognostic impact of brisk tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TILS) in MCC in general.38 Moreover, intratumoral CD8+ lymphocytes have now been recognized as the principle effectors of anti-tumoral immunity.39 The rarity of CSR of MCC has been an obstacle to pursuit of detailed immunological studies in this exceptional setting. We recently re-visited a case of CSR of metastatic MCC reported from our center.29 The primary tumor exhibited brisk TILS (Fig. 1) and high intratumoral CD8+ lymphocyte counts were demonstrated.40 Although these findings appeared to confer a favorable immune profile on the tumor, they did not differ significantly from those of other cases in the cohort which did not undergo regression. Hence the key to CSR remained elusive from a morphological perspective.

Since the discovery of the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in 2008, this agent has been implicated in the pathogenesis of the tumor in the majority of cases.41 Recent work has shown that brisk TILS in MCC has been linked to MCPyV positivity and both have been associated with improved survival.42 It seems likely that they are colluding factors in the generation of an anti-tumoral immune response. Although many reports of CSR of MCC were published since 2008 none of them documented the viral status of the tumor.19-34 As part of the re-examination of our case, (discussed above), we determined that the tumor was MCPyV positive.40

Comment and conclusion

In generating the current overview the objective was to encapsulate current knowledge of CSR of MCC and I regret any omission of relevant contributions to the literature, particularly those published in Japanese. It is time now to focus on this topic given the promising results seen with new immunotherapies for cancer in general, and for MCC in particular. In the latter context, therapeutic blockade of the programmed death-1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint in patients with advanced MCC has shown 62% and 44% response rates in those with MCPyV positive and negative tumors, respectively.43

Contrasted with the paradoxical effect of regression in melanoma, which is associated with a poor prognosis, CSR of MCC usually results in a cure. The former has been attributed by some to the ‘Hammond effect’, whereby higher levels of host immune competence were found to be associated with increased de-differentiation of tumors and enhanced progression.44, 45 Unlike melanoma, the pathogenesis of which is complex, it may be that the etiologic role of MCPyV in MCC confers an inherent immune-stimulatory signal on the tumor cells, rendering them uniformly susceptible to a systemic host response to the virus. It is known that the seroprevalence of MCPyV varies with age and likely over time in the same individual.46 Perhaps a key catalyst, such as further exposure to a high volume of the virus in a patient with MCC, could boost anti-viral immunity to a level capable of eliminating all virus-laden tumor cells?

Notwithstanding the favorable responses to selective immunotherapy observed in patients with MCPyV positive and MCPyV negative tumors, further exploration of the viral status of MCCs which have undergone CSR remains of interest. This data, coupled with serological evaluations in real time and immunophenotypic studies of tumor tissue should be enlightening. In the words of the esteemed British physician William Harvey ‘Nature is nowhere accustomed more to openly display her secret mysteries than in cases where she shows tracings of her workings apart from the beaten paths….’ The answers are there, it is a matter of finding them!

Acknowledgements

I am pleased to acknowledge the clerical assistance of Ms Patsy Morgan in compiling the manuscript and thank Mr Stephen Whitefield for taking the photomicrographs.