Long-term Outcomes after Truncus Arteriosus Repair: A Single-center Experience for More than 40 Years

Conflicts of interest: None.

Disclosure of grants or other funding; No funding was provided for the work described in study.

Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to analyze long-term survival and functional outcomes after truncus arteriosus repair in a single institution with more than 40 years of follow-up.

Methods

Medical records were analyzed retrospectively in 52 patients who underwent the Rastelli procedure for truncus arteriosus repair between 1974 and 2002. Thirty-five patients survived the initial repair. The median age at the initial operation was 2.8 months (range, 0.1–123 months) and the body weight was 3.9 kg (range, 1.6 to 15.0 kg).

Results

The median age at follow-up was 23.6 years (range, 12.4 to 44.5 years). The median follow-up duration was 23.4 years (range, 12.3 to 40.7 years). The actuarial survival rate was 97% at 10 years and 93% at both 20 years and 40 years after the initial operation. At follow-up, most patients were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classes I (73%) and II (24%). Thirty-six percent of patients had full-time jobs, 40% were students, and 21% were unemployed. Most patients (97%) had undergone conduit reoperations. Freedom from reoperation for right ventricular (RV) outflow and pulmonary artery (PA) stenosis was 59% at 5 years, 28% at 10 years, and 3% at 20 years after the initial operation. Freedom from catheter interventions for RV outflow and PA stenosis was 59% at 5 years, 47% at 10 years, and 38% at 20 years after the initial operation. Freedom from truncal valve replacement was 88% at 5 years, 85% at 10 years, and 70% at 20 years after the initial operation.

Conclusions

In this single-center retrospective study, with long-term follow-up after repair of truncus arteriosus, long-term survival and functional outcomes were acceptable, despite the requirement for reoperation and multiple catheter interventions for RV outflow and PA stenosis in almost all patients, and the frequent requirement for late truncal valve operations.

Introduction

Truncus arteriosus is an uncommon complex heart disease occurring in less than 3% of all cases of congenital heart disease.1 A single arterial trunk arises from the biventricular heart, supplying the systemic, coronary, and pulmonary circulations. Only 15% to 30% of patients with this disease survive beyond the first the year of life without surgical intervention.2 McGoon and Rastelli reported the first successful surgical repair using an aortic homograft in 1967.3 Although the mortality of operation was high initially, surgical results have improved. As a result, the survival rate of postoperation has increased and many patients survive to reach adulthood.4 Several studies have reported that reoperation for right ventricular (RV) outflow stenosis is frequently required in the mid-term after the initial operation.5-10 However, there are few studies regarding long-term outcomes of this disease. In this study, we examined the long-term results over 40 years of follow-up after truncus arteriosus repair in a single institution.

Methods

Fifty-two patients had undergone truncus arteriosus repair between 1974 and 2002. There were 35 (67%) survivors and 17 (33%) hospital deaths. All patients were followed at our institution at the time of this study in 2014. The clinical profile of patients is summarized in Table 1. A retrospective review of medical records was performed to assess the outcomes of these patients. The median age at the initial operation was 2.8 months (range, 3 days to 123 months), with a median body weight of 3.9 kg (range, 1.6 and 15.0 kg). In 20 of 35 patients (57%), the operation was performed using a conduit of glutaraldehyde-preserved equine pericardium (Xenomedica, Tokyo, Japan). Other operative methods and conduits used were direct anastomosis of RV and PA (n = 5), porcine valve conduit (Hancock conduit) (n = 7), autologous pericardium conduit (n = 2), and homograft (n = 1). Before the initial operation, truncal valve regurgitation was as follows: none in 74%, mild in 6%, and moderate in 20%. Associated anomalies were interruption of the aorta (n = 1), chromosome 22q11.2 deletion (n = 3), and pulmonary artery (PA) stenosis or interruption (n = 3) (Table 1).

| Survivor Group (n = 35) | Hospital-death Group (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at operation (months), median (range) | 2.8 (0.1–123) | 2.2 (0.3–75.7) |

| BW at operation (kg), median (range) | 3.9 (1.6–15.0) | 2.9 (2.1–15.0) |

| Type of truncus arteriosus | ||

| Type I | 23 (66%) | 12 (71%) |

| Type II | 12 (34%) | 5 (29%) |

| Truncal valve regurgitation | ||

| None | 26 (74%) | 10 (59%) |

| Mild | 2 (6%) | 0% |

| Moderate | 7 (20%) | 2 (12%) |

| Severe | 0 | 5 (29%) |

| Associated anomalies | ||

| Interruption of the aorta | 1 | 1 |

| 22q11.2 deletion | 3 | 0 |

| PA stenosis, interruption | 3 | 3 |

- BW, body weight; PA, pulmonary artery

- Type of truncus arteriosus was classified according to Collett and Edwards classification.11

Statistical Analysis

Data is presented as the median and range. The rates of actuarial survival, freedom from and time to operation for RV outflow and PA stenosis, truncal valve regurgitation, and catheter interventions were predicted by using Kaplan-Meier curves. Potential risk factors for hospital death and truncal valve operation were analyzed using proportional hazard regression performed as the conditional forward stepwise procedure. All analyses were performed using JMP pro 11 (SAS Institute Inc., Tokyo, Japan). A value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Mortality

Early mortality was seen in 17 patients (33%). Of these 17 patients, 11 patients were operated on between 1974 and 1989 (overall mortality 39%), 4 patients between 1990 and 1994 (mortality 44%), and 2 patients between 1995 and 2002 (mortality 13%). Seven (41%) of the 17 patients with early death had moderate to severe truncal valve regurgitation. The main risk factor for hospital mortality was moderate to severe truncal valve regurgitation (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the type of truncus arteriosus between the survivor group and the hospital-death group (Table 1).

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | |||

| Variable | (95% CI) | P Value | (95% CI) | P Value |

| Age at operation | 1.25 (0.91–2.09) | .11 | 1.40 (0.99-2.41) | .052 |

| BW at operation | 1.08 (0.87–1.48) | .51 | ||

| Gender | 0.75 (0.23–2.48) | .29 | ||

| Period (1974–1994 versus 1995–) | 4.43 (1.03–31.0) | .05 | 4.95 (0.99–39.3) | .054 |

| Truncal valve regurgitation (moderate to severe) | 2.80 (0.78–10.3) | .11 | 4.60 (1.06–23.2) | .04 |

| Interruption of the aorta | 2.13 (0.08–56.0) | .61 | ||

| 22q11.2 deletion | .12 | .21 | ||

| PA stenosis, interruption | 2.29 (0.38–13.7) | .35 | ||

- BW, body weight; PA, pulmonary artery.

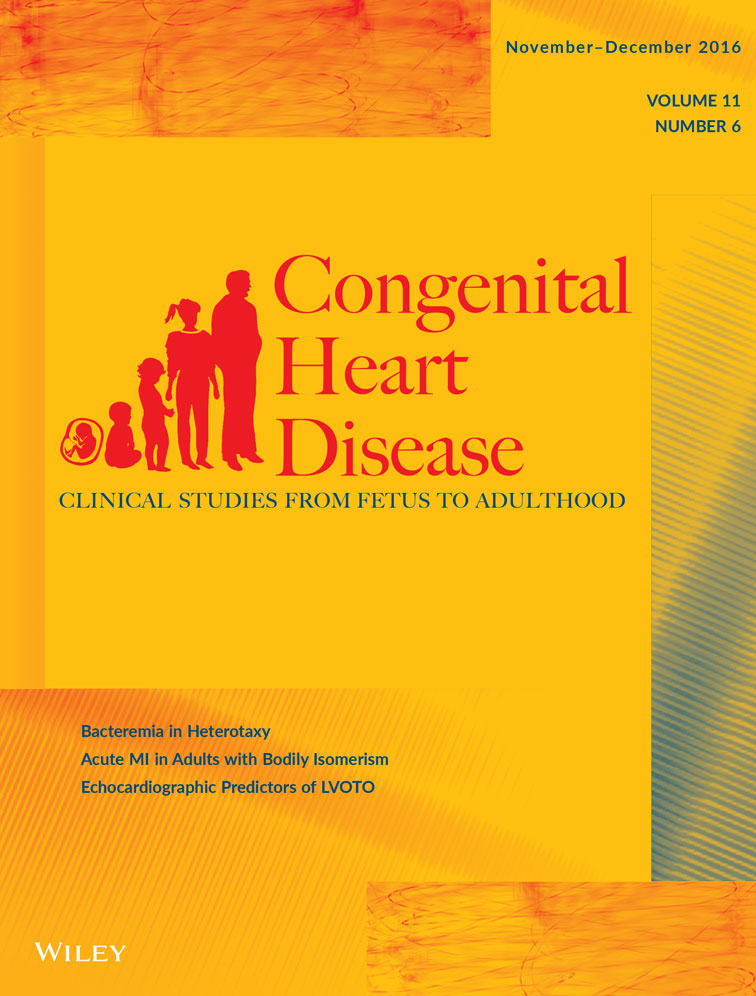

There were two late death (7%) due to infection and cerebral hemorrhage. The actuarial survival rate was 97% at 10 years and 93% at 20 years, 30 years, and 40 years after the initial operation (Figure 1).

Actuarial survival among hospital survivors after truncus arteriosus repair.

Functional Outcomes

At the time of follow-up, NYHA functional class was class I in 24 patients (73%), class II in 8 (24%), and class III in 1 (3%). Twelve patients (36%) were full-time employees, 1 (3%) was a part-time employee, 13 (40%) were full-time students, and 7 (21%) were unemployed.

Reoperation for RV Outflow and PA Stenosis

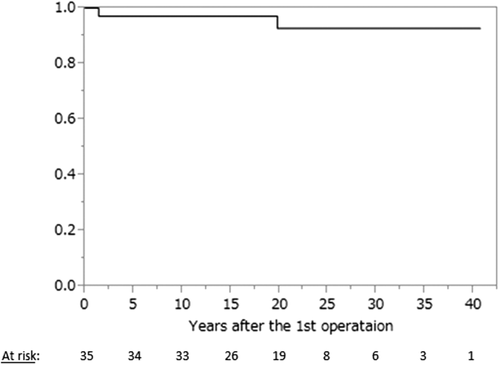

The number of repeat operations was zero in 1 patient (3%), one in 25 (76%), two in 3 (9%), and three in 4 (12%). The median time to reoperation for RV outflow and PA stenosis was 6.1 years, and the freedom from reoperation for RV outflow and PA stenosis was 59% at 5 years, 28% at 10 years, 9% at 15 years, and 3% at 20 years after the initial operation (Figure 2A). Freedom from a third operation for RV outflow and PA stenosis was 94% at 5 years; 85% at 10 years and 15 years; and 78% at 20 years, 30 years, and 40 years after the initial operation (Figure 2B).

(A) Actuarial freedom from the second operation for RV outflow and PA stenosis. (B) Actuarial freedom from the third operation for RV outflow and PA stenosis.

Catheter Interventions

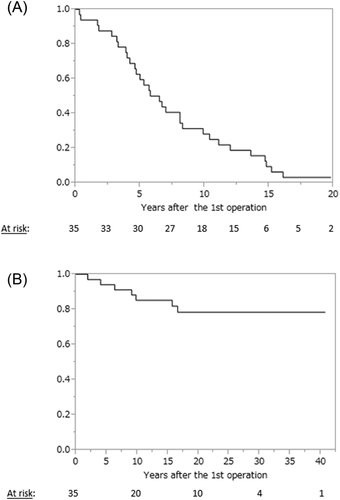

Catheter interventions were performed once in 14 patients (42%) and more than once in 8 (24%). Freedom from catheter interventions for RV outflow and PA stenosis was 59% at 5 years, 47% at 10 years; 38% at 15 years; and 38% at 20 years, 30 years, and 40 years after the initial operation (Figure 3). Four patients (12%) underwent stent placement. Twenty-two patients had both catheter interventions and surgical interventions. All of these patients underwent catheter intervention before surgical intervention. Catheter intervention was effective in 68% and insufficient in 32%. The median pressure gradient before catheter intervention was 50 mm Hg, ranging from 14 to 130 mm Hg, and the median pressure gradient after catheter intervention was 30 mm Hg, ranging from 0 to 120 mm Hg.

Actuarial freedom from catheter intervention for RV outflow and PA stenosis.

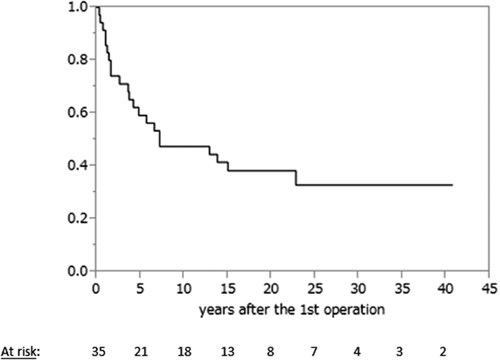

Operation for Truncal Valve

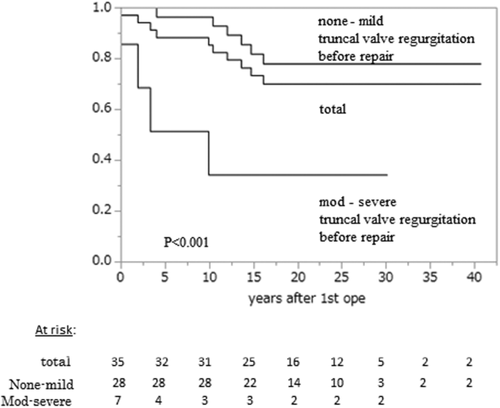

Truncal valve regurgitation at the time of operation was none in 26 patients (74%), mild in 2 (6%), and moderate in 7 (20%). During the follow-up period, 8 truncal valve replacements and 2 aortoplasties were performed. Replacement valves used were 7 mechanical valves and 1 biologic valve. Freedom from truncal valve operation was 88% at 5 years; 85% at 10 years; 73% at 15 years; and 70% at 20 years, 30 years, and 40 years after the initial operation (Figure 4). Truncal valve regurgitation was a risk factor for subsequent truncal valve operation (Figure 4, Table 3).

Actuarial freedom from truncal valve operation among hospital survivors after truncus arteriosus repair. Actuarial freedom from truncal valve operation among hospital survivors after truncus arteriosus repair according to degree of assessed truncal valve regurgitation before initial operation.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | |||

| (95% CI) | P Value | (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age at operation | 8.98 (0.64–90.9) | .10 | 0.61 (0.12-4.18) | .57 |

| BW at operation | 5.80 (0.24–74.7) | .25 | 1.39 (0.71-2.37) | .30 |

| Truncal valve regurgitation (moderate to severe) before 1st operation | 6.29 (1.57–22.7) | .012 | 10.58 (1.61–93.0) | .02 |

- BW, body weight

Discussion

The development of medical and surgical techniques has improved survival rates of congenital heart disease (CHD), and many patients are now surviving to adulthood.12 Similar to other CHDs, good mid-term prognosis of truncus arteriosus has been reported in recent years.5-10 However, long-term prognosis of truncus arteriosus remained unknown. In this study, we found that long-term survival and the functional status are acceptable over 40 years of follow-up after truncus arteriosus repair. This is, to our knowledge, the first report describing long-term functional outcomes after truncus arteriosus repair.

McGoon and Rastelli reported the first successful surgical repair of truncus arteriosus using an aortic homograft in 1967.3 Initially, the surgical mortality rate was high, at around 20%.5, 13 In our institute, we have performed truncus arteriosus repair since 1974. There were 17 (31%) in-hospital deaths. Initially the hospital death rate was high, but this improved after 1995. It must be noted that this study consists of a selected population who survived the surgery 20–40 years ago. The long-term prognosis of patients who have undergone surgery for truncus arteriosus in more recent years is unknown. Recent surgical developments have enabled truncal repair in neonates and young infants, so pulmonary obstruction disease may be less frequent. On the other hand, long-term outcomes may be worse because operations may be performed more frequently in very sick infants with comorbidities.

In this study, we showed that almost all patients required reoperation and interventions for RV outflow and PA stenosis. And, in the first 30 years after the initial operation, a quarter of patients required a third operation for RV outflow and PA stenosis. Previous investigators also reported that 34–50% of patients required reoperation for conduit dysfunction and branched PA stenosis.5, 6, 13-15 Truncus arteriosus repair requires a small conduit in neonates and young infants, which inevitably results in RV outflow or branch PA stenosis. Hence, frequently further operations or balloon angioplasty is needed. Catheter intervention was effective in two-thirds of patients. Catheter intervention may not be able to avoid reoperation; however, it may be able to prolong the duration till repeat surgery.

Moderate to severe truncal valve regurgitation may result in progressive right and left ventricular dysfunction if surgical timing is delayed.16 Hence, truncal valve regurgitation may be a predictor of poor long-term results.10, 17 On the other hand, Henaine et al. reported that truncal valve regurgitation was not a risk factor for late death.18 Similarly, Vohra et al. described that even if truncal valve regurgitation was moderate to severe, excellent long-term survival outcomes were obtained by aggressive truncal valve repair.17 In agreement with these reports, we have performed aggressive intervention for truncal valve regurgitation and no late deaths associated with truncal valve regurgitation have been observed.

In the present study, late death was observed in 7% (Figure 1). In concordance with the present study, several studies have reported that the late death rate was about 10%.5, 14 As survival rate has improved, good functional outcome including exercise capacity, education and occupation in the long-term become important in patients with CHD. 12, 19-22 However, in general, many patients with adult CHD may have an inadequate functional outcome. 19-22 Crossland et al. showed that 33% of adult CHD patients were unemployed whatever the severity of CHD.20 Although many studies have reported compromised functional outcome in general, 19-21 there are few reports regarding functional outcome in specific CHD, including truncus arteriosus. In patients who underwent truncus arteriosus repair, numerous reinterventions for RV outflow, PA stenosis, and truncal valve regurgitation were required. Nevertheless, the present study showed that most survivors were in NYHA functional class I or II, and about 76% of patients had full-time jobs or were students. This suggests that the long-term functional outcomes are acceptable in patients with truncus arteriosus. It must be noted that the present study did not survey detailed functional outcome score and that is the limitation of this study.

Conclusions

In this single center retrospective study, at long-term follow-up for more than 40 years after repair of truncus arteriosus, most patients were in NYHA functional class I or II, and only 21% were unemployed. Long-term survival and functional outcomes are acceptable despite reoperation and multiple catheter interventions for RV outflow and PA stenosis are required in almost all patents within 15 years, and late truncal valve operation is frequently required.

Author Contributions

Seiji Asagai, Kei Inai, Tetsuko Ishii: Design of the study, data analysis/interpretation, Tokuko Shinohara, Hirofumi Tomimatsu, Mitsugi Nagashima: Data analysis/interpretation, Hisashi Sugiyama: Statistics, data analysis/interpretation, In-Sam Park, Toshio Nakanishi: Data analysis/interpretation, final approval of the article.