Trends in use of specialized formula for managing cow's milk allergy in young children

Shriya Mehta and Hilary I. Allen contributed equally to the manuscript.

Funding information

This study was funded through an Irish College of General Practice Research Fellowship awarded to Dr Allen.

This article includes Author Insights, a video abstract available at: https://youtu.be/mh0-uBSQPUM

Abstract

Background

Excessive use of specialized formula for cow's milk allergy was reported in England, but complete analysis has not been undertaken and trends in other countries are unknown. Some specialized formula products, especially amino-acid formula (AAF), have high free sugars content. We evaluated specialized formula trends in countries with public databases documenting national prescription rates.

Methods

Cross-sectional analysis of national prescription databases in the United Kingdom, Norway and Australia. Outcomes were volume and cost of specialized formula, and proportion of infants prescribed specialized formula. Expected volumes assumed 1% cow's milk allergy incidence and similar formula feeding rates between infants with and without milk allergy.

Results

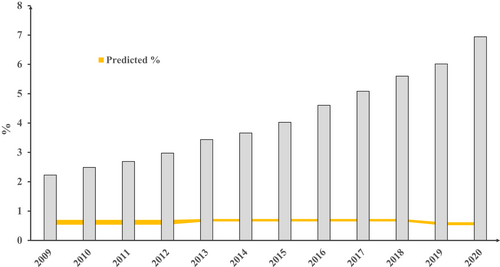

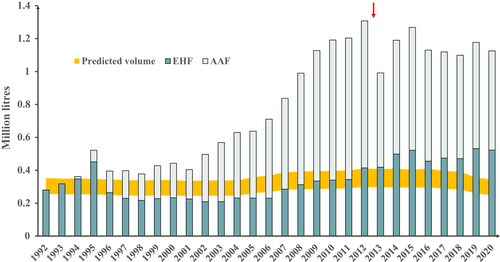

Prescribed volumes of specialized formula for infants rose 2.8-fold in England from 2007 to 2018, with similar trends in other regions of the United Kingdom. Volumes rose 2.2-fold in Norway from 2009 to 2020 and 3.2-fold in Australia from 2001 to 2012. In 2020, total volumes were 9.7- to 12.6-fold greater than expected in England, 8.3- to 15.6-fold greater than expected in Norway and 3.3- to 4.5-fold greater than expected in Australia, where prescribing restrictions were introduced in 2012. In Norway, the proportion of infants prescribed specialized formula increased from 2.2% in 2009 to 6.9% in 2020, or 11.2- to 13.3-fold greater than expected. In 2020, specialized formula for infants cost US$117 (103 euro) per birth in England, US$93 (82 euro) in Norway and US$27 (23 euro) in Australia. Soya formula prescriptions exceeded expected volumes 5.5- to 6.4-fold in England in 1994 and subsequently declined, co-incident with public health concerns regarding soya formula safety. In 2020, 30%–50% of prescribed specialized formula across the three countries was AAF.

Conclusions

In England, Norway and Australia, specialized formula prescriptions increased in the early 21st century and exceeded expected levels. Unnecessary specialized formula use may make a significant contribution to free sugars consumption in young children.

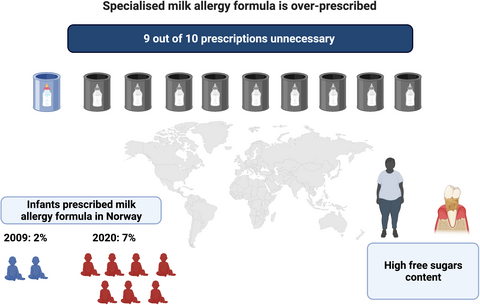

Graphical Abstract

Specialized formula prescriptions in England, Norway and Australia increased ≥2-fold in the early 21st century. Most infants prescribed specialized formula do not have milk allergy, with up to 10-fold excess prescription. Unnecessary specialized formula use increases free sugars consumption so may promote dental decay and obesity (graphic created using BioRender.com).

Key Messages

- Specialized formula prescriptions in England, Norway and Australia increased ≥2-fold in the early 21st century

- Most infants prescribed specialized formula do not have milk allergy, with up to 10-fold excess prescription

- Unnecessary specialized formula use increases free sugars consumption so may promote dental decay and obesity.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cow's milk allergy affects up to 1% of children before the age of 2 years.1 Most infant formula is derived from cow's milk, so for infants with milk allergies who are not fully breastfed, specialized formula products have been developed as alternatives to cow's milk-based formula. Prescriptions for specialized formula are thought to have risen in England, and a 2006 report from Australia documented increasing prescriptions of amino-acid formula (AAF), but no comprehensive analysis of all specialized formula products across multiple countries has yet been undertaken.2-4

Increasing specialized formula use has been interpreted as evidence for milk allergy overdiagnosis, leading to the use of specialized formula for managing common infant symptoms.2, 3, 5 This is because there is little evidence in high-income countries for a change in milk allergy incidence to explain rises in specialized formula prescription.2 While specialized formula is reasonably well tolerated by most infants, and supports infant nutrition and growth, there are significant differences from standard cow's milk-based infant formula or human breastmilk.6, 7 In specialized formula products, the lactose naturally present in breastmilk or cow's milk is partially or completely replaced by alternative carbohydrate sources, often free sugars such as glucose or sucrose.6 High free sugars intake is an important risk factor for obesity and dental decay, and a major public health issue.8 Thus, it is conceivable that unnecessary use of specialized formula may have important public health consequences that have not been studied to date.6, 8-10

We therefore undertook a cross-sectional survey of national prescription databases recording reimbursement of specialized formula for managing formula-fed infants with cow's milk allergy, to better understand recent trends in specialized formula use.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of national prescription databases to obtain reimbursement or sales data for specialized formula. Inclusion criteria were comprehensive prescription databases with complete national data for at least one type of specialized formula for at least 1 year. Exclusion criteria were databases without any complete national data, databases without a detailed breakdown of specialized formula brands and quantities reimbursed or sold, or regions where there is no public record of reimbursed or sold specialized formula volumes. We initially reviewed Euromonitor, an industry database of global and national infant milk formula sales data, but comprehensive data for specialized formula for managing milk allergy were not available. We then contacted colleagues from 23 countries covering over half of the world's population to assess the accessibility of national prescription records, of which three countries had publicly available national prescription data: the United Kingdom, Norway and Australia, (Table S1). We reviewed breastmilk substitute products for infants with cow's milk allergy and excluded semi-solid or solid foods and specialized formula products specifically designed or reimbursed for use in infants with malabsorption or eosinophilic oesophagitis (Table S2). The primary outcome of interest was the volume of specialized formula prescribed annually to children under 1-year old in each country. Secondary outcomes were the annual cost of specialized formula reimbursement and the relationship between reimbursed volumes and expected volumes based on national feeding data and an estimated 1% incidence of milk allergy.1

2.2 Data collection

Quantity and cost of specialized formula reimbursements were collected from national databases. Annual live birth rates and national formula-feeding rates were collated from relevant public databases to estimate the expected quantity of specialized formula consumption (Tables S3–S5). In England, prescription data for specialized formula reimbursed by the National Health Service (NHS) were obtained from Prescription Cost Analysis reports held at the British Library in hard copy (1991–1997), and digital reports held at the National Archives (1998–2003), and NHS Digital Prescription Cost Analysis website (2003–2020). In Scotland, prescription data were obtained from Public Health Scotland Community Dispensing Prescription Cost Analysis website (2001–2019), in Northern Ireland from the Health and Social Care Business Services Organization Prescription Cost Analysis website (2000–2020) and in Wales from NHS Wales Prescription Cost Analysis website (2017–2020). Where relevant, quantities reimbursed were multiplied by the product size to yield the total grams of powdered formula reimbursed. Annual live birth rates were obtained from birth characteristics datasets on the relevant national statistics website for each country. In Norway, prescription data for reimbursed specialized formula for both 0–11 and 12–23-month-old infants were obtained on request from the Norwegian Directorate for Health along with the unique number of users of this group of products. The quantities reimbursed were multiplied by the product size to yield the total grams of powdered formula reimbursed. Annual live birth rates were obtained from Statistics Norway. In Australia, prescription data for specialized formula reimbursed under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and Repatriation PBS were obtained from the Services Australia website, multiplying the number of prescriptions by the number of items claimed per prescription to yield the total grams of powdered formula reimbursed. The annual live birth rates dataset was retrieved from the Australian Bureau of Statistics website.

2.3 Data analysis

Specialized formula quantities were standardized to volume, using the British National Formulary for Children online version (United Kingdom) or manufacturer (Norway and Australia) recommended weight-to-volume for preparation of liquid formula feeds, in grams per liter. Total reimbursement costs were summarized in the local currency and converted to United States Dollars ($US) and euros using mid-2020 currency conversion rates.

The number of infants expected to be diagnosed with milk allergy was estimated as 1% of annual live births.1 The proportion of milk-allergic infants expected to use formula milk was estimated using national infant feeding survey data. The volume of specialized formula expected to be consumed was estimated using reference daily formula consumption values of 780 mL for 0–5.9-month-old and 600 mL for 6–11.9-month-old infants.11

3 RESULTS

Community prescription data were available from England (1991–2020), Norway (2009–2020) and Australia (1992–2020). Data were available for other regions of the United Kingdom for shorter periods of time and are summarized separately. Data for extensively hydrolysed formulas (EHF) and AAF were available from all three countries and data for soya formula were from England and Norway only. Data for the number of infants prescribed a specialized formula were only available from Norway. The specific eligible products available for public reimbursement in each country are summarized in Table 1, and products excluded from the analysis are listed in Table S2.

| Australia | England | Norway | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soya formula | |||

| Farley's OsterSoy formula | - | 1991–1993 | - |

| Farley's soya | - | 1998–2015 | - |

| Infasoy | - | 1998–2019 | - |

| ProSobee | - | 1998–2008 | 2009–2010 |

| ProSobee concentrated liquid | - | 1991–1999 | - |

| SMA Wysoy | - | 1998–2019 | - |

| Extensively Hydrolysed formula | |||

| Alfaré | 1992–2020 | 2001 | 2009–2020 |

| Althéra | - | 2013 | 2009–2020 |

| Alimentum | - | 2013–2019 | - |

| Aptamil Gold+ Pepti-Junior | 1998–2020 | - | - |

| Aptamil Pepti/Cow and Gate Pepti | - | 2010 | - |

| Aptamil Pepti 1 | - | 2011–2019 | - |

| Aptamil Pepti 2 | - | 2011–2019 | - |

| Milupa Prejomin | - | 1991–2010 | - |

| Nutramigena | 1992–2001 | 1998–2016 | 2009–2018 |

| Nutramigen 1 Lipil | - | 2004–2019 | 2009–2020 |

| Nutramigen 1 with LGG | - | 2015–2019 | - |

| Nutramigen 2 Lipila | - | 2003–2019 | 2009–2020 |

| Nutramigen 2 with LGG | - | 2015–2019 | 2009–2010 |

| Nutramigen 3b | - | 2018–2020 | - |

| Pepticate | - | - | 2013–2020 |

| Pepticate Plusb | - | - | 2016–2020 |

| Profylac | - | - | 2009–2017 |

| Amino acid formula | |||

| Alfamino | 2014–2020 | 2014–2019 | 2014–2020 |

| Elecare | 2002–2020 | - | - |

| Elecare LCP | 2010–2020 | - | - |

| Neocate | 1994–2012 | 1998–2019 | - |

| Neocate activeb | - | 2007–2020 | 2009–2020 |

| Neocate advanceb | 2004–2020 | 1999–2020 | 2009–2020 |

| Neocate advance tropical flavourb | 2007–2015 | - | - |

| Neocate Gold | 2011–2020 | - | - |

| Neocate Juniorb | 2017–2020 | 2017–2020 | 2019–2020 |

| Neocate Junior Vanillab | 2012–2020 | 2017–2020 | - |

| Neocate LCP | 2007–2020 | 2008–2019 | 2009–2020 |

| Neocate Nøytral Pulvb | - | - | 2009–2011 |

| Neocate Syneo | 2018–2020 | 2018–2019 | - |

| Nutramigen AA Lipil | - | 2008–2014 | 2009–2016 |

| Nutramigen PurAmino | - | 2014–2020 | 2015–2020 |

- a In Norway, these include Nutramigen Farmag Nøytral Pulv, Nutramigen Pulv, Nutramigen Pulver Nøytral (“Nutramigen”); and Nutramigen 2 Farmag Pulv, Nutramigen 2 DHA Pulv, Nutramigen 2 Lipil Farmag, Nutramigen 2 Pulv (“Nutramigen 2 Lipil”).

- b Marketed for children age over 1 year.

3.1 Trends in volume of reimbursed specialized formula

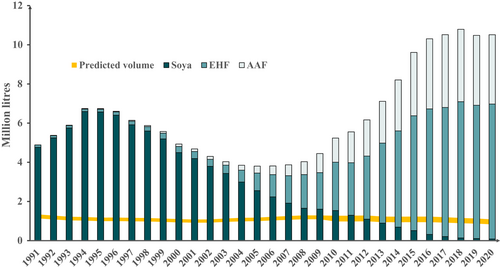

Data for specialized formula products marketed for infants less than 1 year in England are shown in Figure 1. Prescribed volumes rose 2.8-fold between 2007 and 2018 without any subsequent rise. This represents a 4.9-fold increase in EHF and a 6.7-fold increase in AAF for those years, accompanied by a decline in the soya formula. There was an earlier rise in volumes of reimbursed soya formula, peaking in 1994 at 5.5–6.4 times greater than expected volume. In 2020, soya represented less than 1% of reimbursed specialized formula volumes, but the total volume of reimbursed specialized formula was 9.7- to 12.6-fold greater than expected. Data for other regions of the United Kingdom showed similar trends (Figures S1–S3). Volumes of reimbursed specialized formula marketed for children over 1 year in England increased to 2019, mainly AAF, without a further rise in 2020, at less than one-tenth the volumes for infants under 1 year (Figure S4).

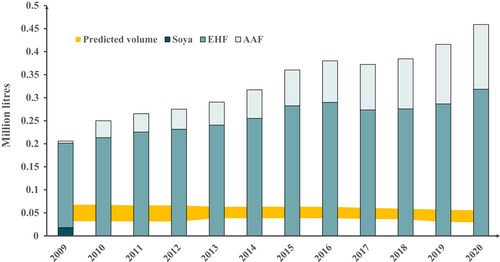

Data for specialized formula products marketed for infants less than 1 year in Norway are shown in Figure 2. Prescribed volumes rose 2.2-fold between 2009 and 2020. This represents a 1.7-fold increase in EHF and a 30.8-fold increase in AAF for those years, with the cessation of soya prescription from 2010 onwards. In 2020, the total volume of reimbursed specialized formula was 8.3- to 15.6-fold greater than expected. Volumes of reimbursed specialized formula marketed for children over 1 year in Norway increased to 2019, mainly EHF, without a further rise in 2020, at approximately one-quarter of the volumes for infants under 1 year (Figure S5). For Norway, data were available on the number and age of children who had received at least one prescription of at least one of the included specialized formula products. These data in relation to the total number of live births are shown in Figure 3. The proportion of infants prescribed specialized formula rose from 2.2% in 2009 to 6.9% in 2020. In 2020, the proportion of Norwegian infants less than 1 year prescribed a specialized formula was 11.2- to 13.3-fold greater than expected. In 2020, 69.7% of specialized formula marketed for infants under 1 year was prescribed for this age group, but 30.3% was prescribed for older children (Figure S6). Similarly, 60.4% of specialized formula marketed for children over 1 year was prescribed for this age group, but 39.6% was prescribed for infants under one (Figure S7).

Data for specialized formula products marketed for infants less than 1 year in Australia are shown in Figure 4. Prescribed volumes rose 3.2-fold between 2001 and 2012. This represents a 1.8-fold increase in EHF and a 5.0-fold increase in AAF for those years. Prescribing restrictions were introduced in late 2012 which mandated specialist consultation for prescription of AAF. Direct sale of EHF and rice-based formula to the public was introduced in 2013 which may also have limited any further rise in reimbursed specialized formula volumes after 2012. Despite the increased availability of EHF outside of the PBS system, reimbursed volumes of EHF continued to increase from 2013 to 2020. In 2012, the last year where data are likely to be complete, the total volume of reimbursed specialized formula was 3.2- to 4.4-fold greater than expected. In 2020, where data are likely to be incomplete due to the availability of EHF and rice infant formula without prescription (i.e. over the counter), the total volume of reimbursed specialized formula was 3.3- to 4.5-fold greater than expected. Volumes of reimbursed specialized formula marketed for children over 1 year in Australia increased to 2012, exclusively AAF, but were also stable between 2013 and 2020 at approximately one-tenth the volumes for infants less than 1 year (Figure S8). In 2020, AAF accounted for 33.7% of prescribed specialized formula in England, 30.6% in Norway and 53.5% in Australia.

3.2 Trends in expenditure on reimbursed specialized formula

Data for expenditure on specialized formula products marketed for infants less than 1 year in England are shown in Figure S9. Prescription costs rose from £4.6 million per annum in 1991 to £59.8 million in 2018 with a fall to £53.5 million in 2020. At the peak of soya formula reimbursement in 1994, the total cost of specialized formula was £7.1 million. AAF accounted for 55% of expenditure in 2020. In 2020 England's public expenditure on specialized formula for managing milk allergy equated to £91 (US$117; €103 euros) per infant born in that year.

Data for expenditure on specialized formula products marketed for infants less than 1 year in Norway are shown in Figure S10. Prescription costs rose from Kr15.9 million per annum in 2009 to Kr46.4 million per annum in 2020. AAF accounted for 54% of expenditure in 2020. In 2020 Norway's public expenditure on specialized formula for managing milk allergy equated to Kr880 (US$93; €82 euros) per infant born in that year.

Data for expenditure on specialized formula products marketed for infants less than 1 year in Australia are shown in Figure S11. Prescription costs rose from AU$1.1 million per annum in 1992 to AU$16.2 million in 2012. Following prescribing restrictions introduced in late 2012, costs fell to AU$10.0 million by 2020. AAF accounted for the majority of specialized formula expenditure from 1996 onwards and 86% in 2020. In 2020, Australia's public expenditure on specialized formula for managing milk allergy equated to AU$39 (US$27; €23 euros) per infant born in that year.

4 DISCUSSION

In this international survey, we identified three countries with comprehensive, publicly available databases of specialized formula prescriptions for infants with cow's milk allergy. In all three countries, there was a marked rise in volumes of specialized formula reimbursed by public health systems in the early 21st century, in the absence of any concurrent evidence for a rise in milk allergy.12-15 The data suggest that by 2020 there was 10-fold excess use of specialized formula for managing milk allergy in the United Kingdom and Norway and at least three-fold excess use in Australia, where non-recorded specialized formula use is likely to be greater than in the United Kingdom and Norway. In Norway, the proportion of infants prescribed specialized formula was at least 10 times the expected levels. These data suggest high levels of milk allergy overdiagnosis and mark an important shift in early child nutrition. The findings fit within a wider picture of global increases in per capita consumption of infant formula, which itself represents an important shift in early child nutrition.16 Rapid increases in AAF reimbursement were first noted in Australia in 2006 and an increase in specialized formula prescriptions in England was reported in 2018 and 2020.2-4 However, this is the first comprehensive evaluation of trends in either country and the first report of trends in Norway. The lack of further increase in AAF prescription in Australia since 2013 is likely due to prescribing restrictions put in place at that time. AAF prescriptions were 2.2- to 3.0-fold higher than expected total specialized infant formula prescriptions in Australia in 2012, compared with 1.4- to 1.9-fold for England and 0.7- to 1.4-fold for Norway; whereas by 2020 AAF rates were up to 4-fold higher than expected in England and Norway, but only up to 2.4-fold higher in Australia. Although EHF has been available since the 1940s, soya formula appears to have been the dominant specialized formula in the late 20th century, at least in England. In the late 1990s, concerns were raised about phytoestrogens in soya formula affecting endocrine development, especially thyroid and reproductive functions.17 These concerns led national governments to recommend against the use of soya formula in the early years of the 21st century, which likely accounts for the decline in soya formula prescriptions and replacement with EHF and AAF.18

Levels of specialized formula prescription now significantly exceed expected levels in these countries. The long-term consequences of this change in early nutrition for a significant minority of the population are unknown. Standard infant formula products derive most of their sugar content from lactose naturally present in cow's milk, which is not considered a free sugar. Although free sugars are added to standard formula products, especially those marketed for children aged over 1 year, free sugars are present in higher quantities in specialized formula products, especially AAF, than in standard infant formula.6 A young infant drinking 780 mL per day of AAF might consume up to 55 g of dried glucose syrup per day, which compares to the United Kingdom Department of Health and Social Care recommended upper limits of 14 g free sugars per day for children aged 2–3 years and 30 g per day for adults.8 Free sugars intake has been linked with dental decay and obesity, which has led the World Health Organization (WHO) and others to recommend limiting total free sugars consumption for both children and adults.6, 8, 19-21 Excessive specialized formula use has been interpreted as a consequence of cow's milk allergy overdiagnosis, which in turn has been associated with adverse effects on maternal quality of life and breastfeeding confidence.2-4 Patient charities, healthcare professionals and the formula industry have all been implicated in contributing to milk allergy overdiagnosis.3 Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of milk allergy may also have played a role in promoting overdiagnosis.5

4.1 Limitations

This study is limited to data analysis of reimbursements from community prescriptions only and does not include direct-to-consumer, non-reimbursed sales. In Australia, these are likely to have been higher than in England or Norway since 2013, which may partly explain the lower rates of specialized formula use in Australia. There is some uncertainty about the assumptions underlying our calculations. Although the most robust estimate of challenge-proven milk allergy incidence in the first 2 years is less than 1%,1 studies using less stringent criteria for diagnosing milk allergy tend to report higher rates.22 We also assumed that formula feeding rates and volumes would be similar in infants with a milk allergy to the general population, and there is little empirical evidence for or against this assumption. However, the Norwegian data on the number of infants prescribed a specialized formula show a similar level of overtreatment to the data for prescribed volumes, suggesting that formula consumption may be similar to population norms in those using specialized formula. We have assumed that milk allergy overdiagnosis is mainly responsible for this observed increase in the use of specialized formula. It is possible that there has been an increase in milk allergy incidence, as recently reported in one Chinese study.23 However, epidemiological studies do not suggest any increase in milk allergy in England or Australia in recent decades.12-15 Finally, data are limited to three, high-income countries and trends in specialized formula consumption may differ in other settings - other methodologies may be needed to develop a complete understanding of global patterns of specialized formula use.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study provides evidence of increased and excessive prescription of specialized formula for managing cow's milk allergy in formula-fed infants in three countries. The data show an important shift in early childhood nutrition which is likely to increase early years free sugars consumption and may promote the development of non-communicable diseases.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr Boyle had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Boyle, Mehta, Allen. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Mehta, Allen, Boyle. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Mehta, Allen, Boyle. Administrative, technical or material support: All authors. Supervision: Boyle.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to staff from the Pricing and Policy Branch of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) Information Management, Department of Health, for their help retrieving data and information on products sold before 2003 in Australia; to Georgina Smith, a statistician from the Statistics and Data Science Team under the Chief Economist's Directorate at the Department of Health and Social Care, for her help retrieving data for products sold before 1998 in England; and to Rebecca S Jones, library manager and liaison librarian at Imperial College London for assistance sourcing historic Prescription Cost Analysis data.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

DEC declares grant funding unrelated to this work from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, part-time employment at DBV technologies who develop food allergy treatments, and advisory board payments from Allergenis and Westmead Fertility Centre. RJB declares consultancy payment from Cochrane, John Wiley and sons and the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology for editorial work, and payment for expert witness work in cases involving food anaphylaxis and a disputed infant formula health claim. All other authors declare they have no competing interests.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.