Prevalence and severity of periodontal disease in the host community and Rohingya refugees living in camps in Bangladesh

Abstract

Objectives

To assess the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease of the Rohingya refugees and host community in Bangladesh.

Methods

An unpublished pilot was conducted for the sample size calculation. Two-stage cluster sampling method was used to select 50 participants from refugee camps and 50 from the host community. Structured questionnaire and periodontal examination were completed. Composite measures of periodontal disease were based on the World Workshop (WW) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-American Academy of Periodontology. Linear regression models, for clinical attachment level and periodontal pocket depth (PPD) and ordered logistic regression models, for composite measures, were fitted to test the association of periodontal measures and refugee status.

Results

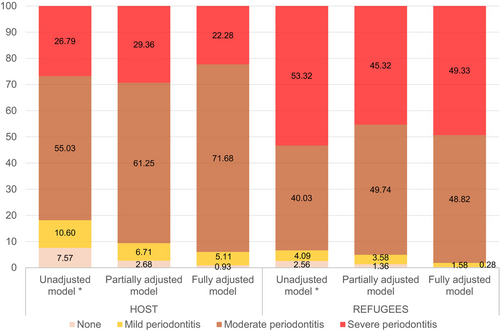

Compared to the host community, a smaller percentage of refugees reported good oral health-related behaviours. Refugees exhibited lower levels of bleeding on probing but higher PPD, hence a higher proportion had severe stages of periodontitis.

As per the WW, prevalence of periodontal disease was 88% and 100% in the host and refugee groups, respectively. In the unadjusted models, refugees were three times more likely to have severe stages of periodontitis; this association was attenuated when adjusted for confounders (sociodemographic variables and oral health-related behaviours).

Conclusions

Prevalence of periodontitis was high both in the host community and refugees. The refugees exhibited a more severe disease profile. The oral health of both groups is under-researched impacting the response of the health system. Large-scale research systematically exploring the oral health of both groups will inform the design and delivery of community-based interventions.

1 INTRODUCTION

A total of 945 953 Rohingya refugees live in the settlements in Bangladesh.4 Due to the absence of census data relating to the Rohingya in Myanmar due to, it is difficult to undertake a systematic review of their health status, however a recent review concluded that the Rohingya people face malnutrition, poor infant and child health, waterborne illness and lack of obstetric care.5someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.3

Oral diseases are highly prevalent with more than 3.5 billion people affected, and due to the close relationship of oral disease with non-communicable disease (NCD), there is a significant health, economic and social burden to consider.6 Specifically, 2.3 billion people have untreated dental caries in permanent teeth, 796 million people have severe periodontitis,7 and oral cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers globally with 180 000 deaths annually.8

Bangladesh is a lower-middle income country that faces significant challenges to the health system.9 In a recent survey, 14.2% of the Rohingya refugees reported challenges in accessing healthcare compared to 32.5% of in the host community, with the most common reasons being the facilities were too far followed by unaffordability of the service.10 A recent cross-sectional study of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh reported low oral health literacy and poor oral health practices with 45% reporting pain or discomfort.11 Oral health assessment of the Rohingya refugees in India found a high prevalence of periodontal disease and caries.12

Periodontitis is characterized by destruction of the tooth-supporting structures which includes loss of clinical attachment, presence of periodontal pocketing and gingivitis.13 It is a major public health problem as it is a leading cause of tooth loss which can have a negative impact on oral health related quality of life.13, 14 Periodontitis has a significant impact on healthcare costs and can account for a major component of the direct and indirect costs of oral disease.15 Considering the global burden of oral disease,7 there is an urgent need to identify and implement effective and evidence-based oral health strategies.

There is no literature on the prevalence of periodontal disease in the Rohingya refugees in the camps in Bangladesh. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease in the Rohingya refugees living in camps and compare it with the host community in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and sample

In 2023, 100 adults from refugee camps and host population in the sub-district of Ukhiya, unions of Palong Khali and Raja Palong, were recruited for this cross-sectional study using a two-stage cluster sampling method.16 Of the 33 refugee camps in the area, approval was granted to conduct the study in eight camps which are organized into blocks. Among the host population, each union is divided into ward (electoral unit) and para (‘neighbourhood’). In each union, camps or wards were considered as clusters and chosen with a probability proportional to their size (i.e. the number of blocks or paras per camp or ward, respectively). This selection procedure guaranteed that each camp or ward had an equal probability of selection. The second stage saw blocks and paras were randomly selected within each chosen camp or ward. Households in the chosen area were screened for eligibility, and invited to participate if they met the inclusion criteria. Recruitment finished when the required sample size was obtained.

A pilot study was conducted among 25 participants in the host community and 25 of the Rohingya refugees to obtain their mean PPD, one of the main outcomes of this study. The sample size calculation (90% power, α =.05 and 20% non-response rate) yielded a total sample size of 98 participants, 49 in the host community and 49 refugees, which was rounded up to 50 per group.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh (Ref: 2022/OR-NSU/IRB/0210). Approval to conduct the study was sought from the Refugee Repatriation and Relief Commissioner.

Only those adults who agreed to participate and signed a consent form were enrolled in the study. As the Rohingya language only exists in oral form, the information sheet and consent form were verbally translated from Bangla to the Rohingya language by a trained translator. The Rohingya refugees that consented to the study were asked to sign or mark an X to signify consent in the presence of a witness who was not affiliated with the research team.

In the host community the information sheet was translated into Bangla. Written informed consent was obtained in Bangla. For illiterate participants in the host community, the same consent process as for the Rohingya refugees.

2.2 Data collection

During a structured interview, participants provided information on their sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, education level and employment status), systemic conditions (diabetes and pregnancy) and oral health-related behaviours (Table S1). Oral hygiene practices were explored asking about their frequency of brushing, instruments (toothbrush, miswak, finger or nil) and adjuncts (toothpaste, salt, charcoal or sand) used for cleaning teeth. Smoking and betel nut (paan) use were also explored, as well as access to a medical doctor and dentist, and last dental visit. Participants self-reported their race and ethnicity which were categorized to host Bangladeshi and Rohingya refugees.

Anthropometric measures (height and weight) were recorded by calibrated examiners following standardized methods.17 Weight was measured on a calibrated scale with the participant wearing light clothing and height was measured with a wall-mounted tape standing barefoot.

Both the male (author MJS) and a female (author II) dentists performing the clinical examinations underwent a calibration process. The inter-examiner calibration required a full mouth examination of 15 participants (Kappa = 0.77; Bland–Altman unstandardised coefficient B mean = −0.003; p = .746; 93.3% agreement) and the intra-examiner calibration consisted of each dentist performing a full mouth examination on five participants twice with 30 min interval between examinations; (Kappa >0.9). Both examiners had experience of working in a dental clinic in the refugee camps. The clinical examinations under artificial headlight using a mouth mirror and a UNC-15 periodontal probe. Probing was performed at six sites per tooth, and all measurements were rounded to the nearest millimetre. The following data was recorded: number of teeth, periodontal probing depth (PPD), bleeding on probing (BoP), recession and tooth mobility.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata MP version 18 (Stata corp. LP, College Station, TX, USA). Data modelling was performed to obtain some periodontal indicators, namely CAL, stages of periodontitis,13 and severity of periodontal disease.18 CAL was calculated adding the PPD and recession measures.19 Composite measures of periodontal disease were based on the 2017 World Workshop (WW),13 and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—American Academy of Periodontology (AAP).18 With the WW classification, participants with interdental CAL ≥5 mm were grouped into stage III–IV.

The association between host/refugee condition and periodontal measures was assessed in separate models for each periodontal indicator and modelled using different regression models according to the outcome; linear regression for mean PPD and CAL, and ordered logistic regression for the WW and CDC-AAP classifications. Linear regression models and ordered logistic regression provide coefficients and Proportional Odds Ratios (POLR), respectively. The association between host/refugee condition and each definition of periodontal disease was assessed in crude and adjusted models using sequential adjustment for socio-demographic factors and systemic conditions (sex, age, education, occupation and diabetes) in the partially adjusted model and additionally for behavioural factors (smoking and paan use, oral hygiene and dental visits) in the fully adjusted model. The directed acyclic graph in Figure S1 provides a visual representation of the variables included in the regression models.

3 RESULTS

This study analysed data on 100 adults (50 from the host community and 50 refugees). The baseline comparison of socio-demographic, behavioural and clinical characteristics between both groups is reported in Table 1. These groups were significantly different in terms of their gender, pregnancy status, access to medical and dental care, toothbrushing instruments and adjuncts, smoking status, BoP, PPD, mobility and both composite measures of periodontal disease. In all, there were more females in the host population and a greater proportion of them were pregnant. Refugees had greater access to medical care but lower access to dental care when compared to the host population, leading to a greater proportion of refugees who had never visited a dentist. A smaller percentage of refugees used toothbrush and toothpaste when cleaning their teeth and a greater proportion were current smokers. Furthermore, refugees exhibited lower levels of BoP but higher PPD and mobility, which is reflected on a higher proportion being classified as having more severe stages of periodontal disease.

| Host | Refugee | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or Mean ± SD | n (%) or Mean ± SD | p-valuea | |||

| Gender | .008 | ||||

| Male | 13 | (26.0) | 26 | (52.0) | |

| Female | 37 | (74.0) | 24 | (48.0) | |

| Education level | .163 | ||||

| None | 40 | (80.0) | 45 | (90.0) | |

| Basic | 7 | (14.0) | 5 | (10.0) | |

| Higher | 3 | (6.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Employment status | .514 | ||||

| Unemployed | 38 | (76.0) | 33 | (66.0) | |

| Unskilled worker | 7 | (14.0) | 11 | (22.0) | |

| Professional/managerial | 5 | (10.0) | 6 | (12.0) | |

| Diabetes | .280 | ||||

| No | 37 | (74.0) | 32 | (64.0) | |

| Yes | 13 | (26.0) | 18 | (36.0) | |

| Pregnant (n = 64) | .016 | ||||

| No | 37 | (100.0) | 23 | (85.2) | |

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 4 | (14.8) | |

| Access to medical care | .004 | ||||

| No | 10 | (20.0) | 1 | (2.0) | |

| Yes | 40 | (80.0) | 49 | (98.0) | |

| Access to dental care | .026 | ||||

| No | 31 | (62.0) | 41 | (82.0) | |

| Yes | 19 | (38.0) | 9 | (18.0) | |

| Last dental visit | .002 | ||||

| Past year | 14 | (28.0) | 2 | (4.0) | |

| Over a year | 4 | (8.0) | 2 | (4.0) | |

| Never | 32 | (64.0) | 46 | (92.0) | |

| Toothbrushing frequency | .673 | ||||

| Once a day | 18 | (36.0) | 16 | (32.0) | |

| Twice or more per day | 32 | (64.0) | 34 | (68.0) | |

| Toothbrushing instrument | .024 | ||||

| Toothbrush | 18 | (36.0) | 8 | (16.0) | |

| Nil | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (2.0) | |

| Miswak | 6 | (12.0) | 2 | (4.0) | |

| Finger | 26 | (52.0) | 39 | (78.0) | |

| Adjunct to clean teeth | <.001 | ||||

| Toothpaste | 18 | (36.0) | 5 | (10.0) | |

| Salt | 0 | (0.0) | 19 | (38.0) | |

| Charcoal | 22 | (44.0) | 26 | (52.0) | |

| Other | 10 | (20.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Smoking status | <.001 | ||||

| Never | 39 | (78.0) | 19 | (38.0) | |

| Former smoker | 0 | (0.0) | 9 | (18.0) | |

| Current smoker | 11 | (22.0) | 22 | (44.0) | |

| Paan use status | .135 | ||||

| Never | 8 | (16.0) | 2 | (4.0) | |

| Former user | 1 | (2.0) | 1 | (2.0) | |

| Current user | 41 | (82.0) | 47 | (94.0) | |

| Stages of Periodontitis (WW) | .021 | ||||

| Healthy | 6 | (12.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Stage II | 8 | (16.0) | 5 | (10.0) | |

| Stage III/IV | 36 | (72.0) | 45 | (90.0) | |

| Periodontal disease (CDC-AAP) | .003 | ||||

| None | 5 | (10.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Mild | 7 | (14.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Moderate | 22 | (44.0) | 25 | (50.0) | |

| Severe | 16 | (32.0) | 25 | (50.0) | |

| Age | 43.5 ± 14.3 | 44.4 ± 16.3 | .773 | ||

| Years smoking | 19.5 ± 17.6 | 18.3 ± 12.4 | .833 | ||

| Cigarettes per day | 7.3 ± 3.0 | 6.9 ± 2.2 | .710 | ||

| Years using paan | 18.1 ± 16.7 | 19.9 ± 14.5 | .606 | ||

| Times paan is used per day | 5.9 ± 4.0 | 6.6 ± 2.8 | .271 | ||

| Number of teeth | 25.9 ± 3.8 | 24.8 ± 4.4 | .274 | ||

| BoP | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | <.001 | ||

| PPD | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | .003 | ||

| CAL | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 0.9 | .763 | ||

| Mobility | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | <.001 | ||

- Abbreviations: BoP, bleeding on probing; CAL, clinical attachment loss; CDC-AAP, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention American Academy of Periodontology; PPD, periodontal pocket depth; SD, standard deviation; WW, World Workshop.

- a Categorical variables were compared using chi-squared test, count variables using negative binomial regression and continuous variables using linear regression.

Of the individual clinical periodontal indicators, only PPD and not CAL, was significantly associated with the host/refugee condition in the unadjusted models (Table 2); in all, the mean PPD among refugees was greater of those of the host community by 0.42 mm (95% CI 0.15–0.68). This association remained significant after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics and oral health-related behaviours, refugees' PPD was 0.34 mm greater than the host community participants.

| Clinical measures | Classification of Periodontitis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPD | CAL | WW | CDC-AAP | |||||

| Coeffc | 95% CI | Coeffc | 95% CI | POLRd | 95% CI | POLRd | 95% CI | |

| Unadjusted model | 0.42** | (0.15–0.68) | −0.09 | (−0.65 to 0.18) | 3.75* | (1.24-11.38) | 3.12** | (1.42-6.85) |

| Partially adjusted modela | 0.31** | (0.09–0.53) | −0.37 | (−0.88 to 0.13) | 1.94 | (0.46–8.24) | 1.99 | (0. 83–4.81) |

| Fully adjusted model Ab | 0.34* | (0.04–0.63) | −0.45 | (−1.11 to 0.21) | 3.63 | (0.46–28.88) | 3.40 | (0.86–13.44) |

- a Adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, education level and occupation) and diabetes.

- b Additionally adjusted oral health-related behaviours (smoking, use of paan, toothbrushing, access to dentist, dental visits).

- c Linear regression models were fitted and coefficients (Coeff) reported.

- d Ordered logistic regression models were fitted and Odds Ratios (OR) reported.

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < .001.

- Abbreviations: CAL, clinical attachment loss; CI, confidence interval; CDC-AAP, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—American Academy of Periodontology; PPD, periodontal pocket depth; POLR, proportional odds logistic regression; WW, world workshop.

Both composite measures of periodontal disease, WW and CDC-AAP, showed a statistically significant association with host/refugee condition in the unadjusted models; refugees were 3.75 (95% CI 1.24–11.38) (WW) and 3.12 (95% CI 1.42–6.85) (CDC-AAP) times more likely to have severe stages of periodontal disease than the host community (Table 2). However, this association was completely attenuated when adjusting for confounders which included sociodemographic variables and oral health-related behaviours (Table 2). Figure 1 presents the predicted probability of periodontal disease according to CDC-AAP; in all, refugees showed a greater probability of severe stages of periodontal disease than the host population.

4 DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was the high prevalence of periodontal disease which affected 100% of the refugees compared to 88% of the host. As per the WW classification, refugees were nearly four times more likely to have a severe disease profile, although this association was not statistically significant when adjusted for confounders.

Low education levels were found in both groups, however this was lower in the refugee group which is in line with other studies.10, 11 Access to dental care was limited for the refugees compared to the host, but vice versa for medical care. Limited access to medical care for the host community has been reported by Bhatia et al.,10 whereby 32.7% of the host reported difficulty in accessing healthcare services compared to 14.2% of the refugees. Following the displacement of nearly 750 000 Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh in 2017, a large-scale response resulted in a vast network of primary and secondary healthcare facilities which might explain improved access to medical services for the refugees compared to the host.20

Apart from a recent paper by Chowdhury et al., there is no literature on the oral health of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.11 The authors reported that nearly half of the participants did not have basic oral health knowledge and required dental care which is in line with the findings from this study. The high prevalence of periodontitis in the refugees could be further explained by the living conditions, and limited access and availability of oral healthcare services and hygiene aids in the camps.21, 22 It is also important to consider the origin of the Rohingya refugees who are a persecuted ethnic minority and stateless in their country of origin, Myanmar. The Rohingya in Myanmar have been reported to have very limited access to primary healthcare which is provided by humanitarian agencies therefore racism/ discrimination and other predisposing factors are key to the observation of oral health inequities.5, 23

One of the strengths of the study is that it is the first one to explore the prevalence of periodontal disease of the Rohingya refugees living in camps in Bangladesh. In addition to this, it directly compares the prevalence of the periodontitis to the impoverished host community. Furthermore, an unpublished pilot study was undertaken which was used to calculate the present study's sample size to the power of 90%. The samples are relatively representative of the population as two stage cluster sampling was undertaken. Full mouth periodontal charting was undertaken by calibrated examiners who were experienced dentists working in the camps. Due to the vulnerable nature of the refugees, it can be challenging to undertake such a study, however by establishing local partnership and collaborations this was made possible.

The limitation of this study is the inclusion of pregnant women of which all four pregnant participants were in the refugee group. Pregnancy exacerbates pre-existing periodontal disease therefore a worse disease profile which would usually resolve following child-birth.24 However, as the primary objective of this study was to report on the prevalence rate of periodontal disease all participants were included.

Refugees without access to oral healthcare services report a negative impact on quality of life.25 The high prevalence of periodontal disease and limited access to dental care highlights the importance of delivering oral health promotion and prevention strategies,25-27 as outlined in the ‘Action Plan for Oral Health in South-East Asia 2022-2030’ by the World Health Organisation28 which identifies strategic action areas including cost-effective and evidence-based interventions to prevent oral diseases.

5 CONCLUSION

Refugees had a higher prevalence of periodontal disease with a more severe disease profile compared to the host community. Refugees were more likely to smoke, had unhealthy oral hygiene practices and limited access to dental care. The oral health of Rohingya refugees is under-researched therefore further research is needed to inform the design and delivery of locally led initiatives focusing on oral health promotion and prevention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the teams at Refugee Crisis Foundation, the Refugee Repatriation and Relief Commissioner, North South University, OBAT Helpers and Prantic Unnayan Society for supporting the study. The authors would like to thank Dr Ahmed Hossain at North South University for facilitating the study. The authors appreciate the contribution of Dr Bachwan Basak for supporting the field work.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data sets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.