Modified cranial approach to right-sided colon cancer in a patient with intestinal nonrotation: A case report

Abstract

Managing colon cancer with intestinal nonrotation, a type of congenital intestinal malrotation, is challenging due to the presence of anatomical abnormalities and severe adhesions. When patients have nonrotation, it is markedly more difficult to determine which vessels correspond to the colic vessels and ileal vessels until all vascular branching patterns become evident. The optimal approach for right-sided colon cancer with intestinal nonrotation has yet to be established. In the present case of ascending colon cancer with intestinal nonrotation, we performed laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with D3 dissection using a modified cranial approach. This approach involves tracing, without resecting, branches from the superior mesenteric vein and superior mesenteric artery in a cranial-to-caudal manner until the ileocolic artery and ileocolic vein, which course toward the cecum, are identified, followed by the dissection of the colic vessels and lymph nodes in a caudal-to-cranial fashion.

1 INTRODUCTION

Intestinal malrotation, a congenital anomaly, results from abnormalities during gut rotation and fixation in embryonic development. In adults, nonrotation is the most common subtype of intestinal malrotation, detected in about 0.15% of patients undergoing computed tomography (CT) colonography.1 Anatomical distortions and severe adhesions in nonrotation cases pose a significant challenge in surgical interventions. This underscores the importance of meticulous planning to ensure safety and favorable outcomes.

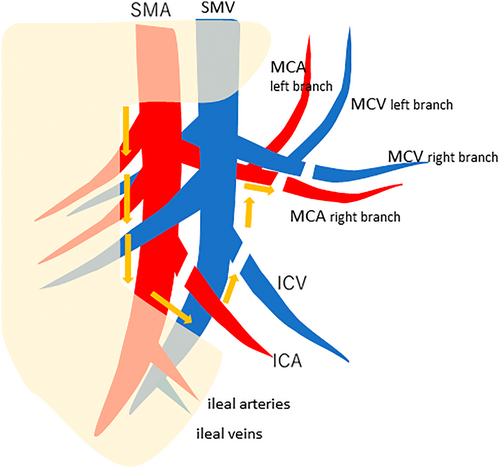

In right-sided colon cancer, five common laparoscopic approaches are employed: medial, inferior, lateral, cranial, and pincer.2, 3 In cases of intestinal malrotation, the medial and pincer approaches pose difficulties because of adhesions between colon segments, and both the lateral and inferior approaches, which involve mesentery separation from the retroperitoneal area, are unsuitable due to the lack of fusion between the mesentery and the lateral abdominal wall. Therefore, the cranial approach is the most suitable option for addressing nonrotation. In nonrotation cases, however, another challenge arises due to the difficulty in distinguishing between vessels of the right-side colon and those of the ileum. This is because not only the vessels of the right-side colon but also some ileal vessels branch to the same side (left side) of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and superior mesenteric vein (SMV). In stark contrast, in normal cases, the vessels of the right-side colon and all ileal vessels branch to the opposite sides, specifically, to the right side and left side of the SMA and SMV, respectively. Thus, in intestinal nonrotation, it is difficult to determine which vessels correspond to the ileocolic artery (ICA) and vein (ICV), right colic artery (RCA) and vein (RCV), middle colic artery (MCA) and vein (MCV), and ileal arteries and ileal veins, until all vessels branching to the left side are identified. Among these vessels, ileocolic vessels (ICA and ICV) are the first ones to be identified because they course toward the cecum. Then, the RCA and RCV (if present), as well as the MCA and MCV can be identified, all of which exist caudal to ileocolic vessels. In the present case, we traced, without resecting, the branches from the SMV and SMA in a cranial-to-caudal manner until the ICA and ICV were identified, followed by the dissection of the colic vessels and lymph nodes in a caudal-to-cranial fashion, to facilitate safe and effective D3 dissection without complications. This unique method, termed the “modified cranial approach,” is distinct from the cranial approach, which is generally performed in a cranial-to-caudal fashion (Figure 1).

1.1 Case presentation

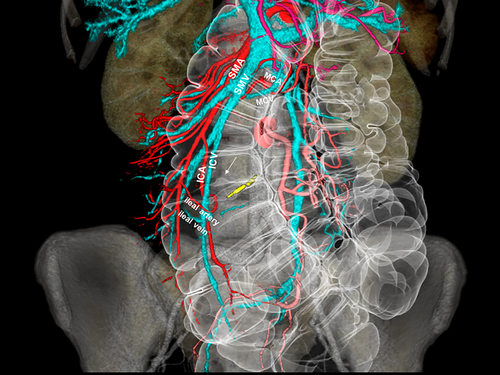

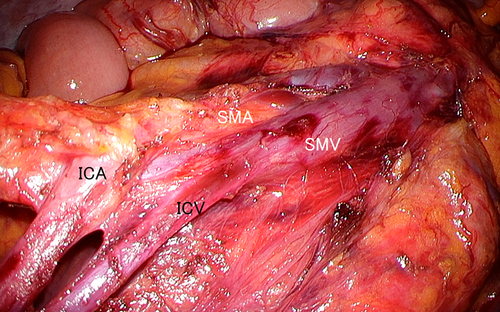

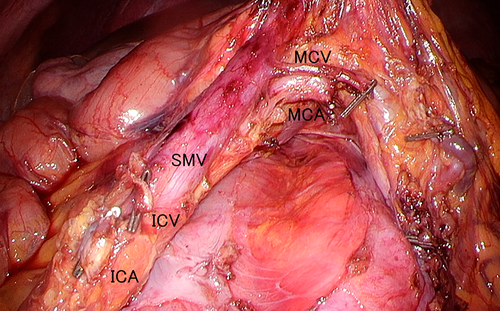

A 49-year-old female presented with melena and colonoscopy at a previous clinic visit and was diagnosed with ascending colon cancer. Colonoscopy revealed an ulcerated invasive tumor 2 cm in size. On enhanced CT, the small bowel occupied the right side of the abdomen, and the colon occupied the left side of the abdomen, indicating intestinal malrotation (nonrotation type) (Figure 2). CT also revealed a tumor in the midascending colon without distant metastasis, with the SMV located on the left side of the SMA (SMV rotation sign) (Figure 2). Our preoperative diagnosis was T2 N0 M0. According to Figure 2, the middle colic artery (MCA) originated from the SMA behind the SMV, and the ICA and ICV branched to the left from the SMA and SMV, respectively. The majority of small intestine arteries branched to the right from the SMA, although some ileal arteries also branched to the left from the distal end of the ICA branch of the SMA. Similarly, some ileal veins also branched to the left from the distal end of the ICV branch of the SMV. Tumor-feeding vessels were the ICA and the right branch of the MCA. Intraoperatively, the small intestine was found to occupy the right side of the abdomen, whereas the cecum and the ascending colon were located along the midline. Laparoscopic colectomy was performed using the modified cranial approach. That is, we first traced the branches from the SMV and SMA, eventually identifying the ICA and ICV which ran toward the ileocolic lesion, distinguishing them from the ileal artery and vein (Figure 3). After dissecting the ICA and ICV, the MCA and MCV became clearer, facilitating the meticulous resection of the right branch while preserving the left branch of both the MCV and MCA (Figure 4). Ladd's ligament was absent. Pathological findings were consistent with T1bN0M0 colon cancer according to the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) classification (eighth edition). See the Video S1, which demonstrates the procedures of laparoscopic surgery using the modified cranial approach.

2 DISCUSSION

The modified cranial approach involves tracing, without resecting, branches from the SMV and SMA in a cranial-to-caudal fashion until the ileocolic vessels (ICV and ICA) are identified and dissecting the colic vessels and lymph nodes in a caudal-to-cranial fashion up to the middle colic vessels (MCA and MCV), thereby safely allowing precise anatomical identification as well as adequate lymph node dissection. While open surgery remains a viable alternative in this scenario, if minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopic surgery can be safely implemented, integrating approaches like our “modified cranial approach” would be advantageous from the perspective of postoperative recovery.

Surgical approaches for right-side colon cancer can be categorized into two types: those in which the right colon is mobilized before vessel ligation, and those in which vessels are ligated before colonic mobilization. The former includes the inferior and lateral approaches, and the latter, the medial, cranial, and pincer approaches. The lateral approach, which has traditionally been used in open colectomy, involves initial lateral mobilization of the colon, followed by sectioning of normal parietocolic attachments and vessel ligation. Similarly, the inferior approach starts with peritoneal dissection between the mesoileum and retroperitoneum, followed by mobilization of the terminal ileum and ascending colon before vessel dissection. In the medial approach, vessels are identified and ligated before medial-to-lateral exploration and protection of retroperitoneal structures (e.g., duodenum, ureter, and gonadal vessels), followed by mobilization and bowel resection. The cranial approach begins with opening of the omental bursa, early exposure and dissection of the middle colic vessels and subsequent lymph node dissection including identification as well as resection of colonic vessels along the surgical trunk in a top-to-bottom manner. This cranial approach has potential benefits: it exposes the gastrocolic trunk early in the procedure, since numerous vascular variations exist around the gastrocolic trunk, and consistently allows for D3 lymph node dissection along the superior mesenteric vessels. In the pincer approach, the transverse mesocolon is approached from both the ventral and dorsal sides while appropriately moving the transverse mesocolon to the caudal and cranial sides to provide a space for ligating and sealing the vessels, and thus, hemostasis can easily be achieved even when active bleeding occurs. For right hemicolectomy in nonrotation cases, the absence of fusion between the mesentery and the lateral abdominal wall renders the inferior and lateral approaches unsuitable. In addition, severe adhesions between colon segments make the medial and pincer approaches impractical.

Wang and Welch4 classified intestinal malrotation into four types: nonrotation, malrotation, reversed rotation, and paraduodenal hernia. Symptomatic cases typically manifest in infancy, with symptoms such as intestinal obstruction due to volvulus. In contrast, adults with intestinal malrotation often remain asymptomatic and are usually incidentally detected during routine medical examinations or unrelated surgical procedures. Intestinal nonrotation, as observed in the present case, is the most common asymptomatic type of adult intestinal malrotation.

Cases of colon cancer with intestinal malrotation have previously been reported.5, 6 Surgery for colon cancer with intestinal malrotation poses challenges due to its atypical anatomy and severe adhesions. Because of vascular anomalies and complexities, laparoscopic surgery is rarely used.7 Precise identification of SMV and SMA positions is crucial for right-sided colon cancer, as they are embryologically pivotal in intestinal rotation. In addition, intestinal and pancreatic branches from the SMV and SMA must be identified carefully, as they may deviate from their usual course.7-9

3 CONCLUSION

We presented a case of colon cancer with intestinal nonrotation which was managed using a modified cranial approach. This technique effectively addressed the challenges posed by intestinal nonrotation during colon cancer surgery.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SM wrote the report and prepared the initial manuscript draft; KD, NS, YA, HO, and SA collected clinical data and coordinated and helped draft the manuscript; and DS wrote the report and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all colleagues and nurses who provided care to the patient.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo (IRB code: 2022–9-0524).

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed.