Adolf Lichtenstein: Drove big improvements within both children’s and epidemic health care

1 INTRODUCTION

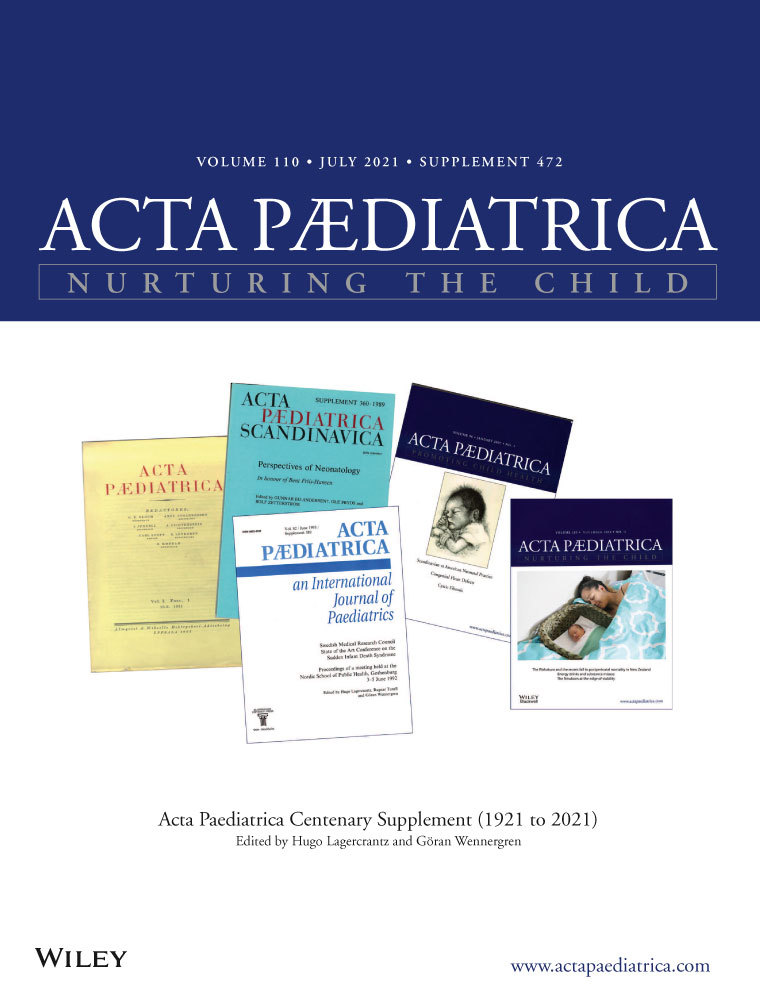

Isak Jundell’s successor as editor-in-chief for Acta Paediatrica was Adolf Lichtenstein (Figure 1). Like Jundell, Lichtenstein came from a Jewish family, but unlike Jundell, Lichtenstein grew up in an affluent environment. Lichtenstein was a powerful person who strengthened Acta Paediatrica’s position as a scientific journal. Because of his sudden passing after just a few years, his time as editor-in-chief was sadly short.

Adolf Lichtenstein (1884-1950) grew up in an affluent Jewish family in Stockholm. His father was a wholesale merchant. Following medical studies at Uppsala and graduating as a doctor of medicine at the Karolinska Institute, he served in Stockholm at the children’s hospital The Samaritan, Sachsska Children’s Hospital and Crown Princess Lovisa’s Hospital for Sick Children.1

Lichtenstein wrote his thesis on anaemia in preterm infants and demonstrated their need for iron supplements. His doctoral defence was at Karolinska Institute year 1917, and he became Associate Professor of paediatrics the same year. After his dissertation, he served as a physician at the infant ward of the Public Maternity Hospital between 1917 and 1924 and consultant physician at the Stockholm Epidemic Hospital between 1924 and 1932. From 1932 to his retirement at the end of 1949, he was a professor of paediatrics at Karolinska Institute and consultant physician and head of the clinical department of Crown Princess Lovisa’s Children’s Hospital.

2 PAEDIATRICIAN FOR THE NEWBORNS

Through his service at the public maternity hospital, Lichtenstein made a pioneering contribution as the first paediatrician working within a maternity ward to examine and monitor the newborns. He went to great efforts to transform both children’s health care and epidemic health care. By influencing politicians and other civil servants, Lichtenstein strongly contributed to the appearance of paediatric clinics even at the hospitals located outside the university towns. Paediatricians were trained in supervising the newborns, and the specialisation within paediatrics began. The epidemic hospitals were replaced by infection clinics that even treated infections not included in the epidemic laws.

Lichtenstein was very active academically. During his time at the epidemic hospital, he studied streptococci and scarlet fever and showed that the occurrence of different streptococcal strains meant that a patient could become re-infected with a new strain. Through adherence to rules of hygiene and isolation, the spread of the infection at hospitals could be prevented. He committed himself to the care of children with diabetes and turned against the strict diet that was prescribed despite that treatment with insulin had become available. Instead, the children were to receive a normal diet and the insulin dose adapted.

3 PRODUCTIVE, VIGOROUS AND WITH UNTIRING ENERGY

In his productivity, Lichtenstein was very broad. He wrote for a generalist audience of parents about the care of children, and he was one of the editors of the Nordic textbook of paediatrics, which for a long time was the textbook (with a capital T) of paediatrics for medical students. Among his many assignments, he also managed to serve as chairman for the Swedish Paediatric Association and the Swedish Medical Association.

Adolf Lichtenstein had been a member of Acta Paediatrica’s editorial board since the start, and he wrote one of the articles in the very first issue. When Isak Jundell passed away in December 1945, Lichtenstein was appointed to succeed him as editor-in-chief. Lichtenstein led Acta Paediatrica with a firm hand, and the journal developed favourably.

Lichtenstein was an impactful person with a strong sense of duty and tireless energy. He expected a lot of his colleagues, but the biggest demands he placed on himself. He died suddenly after a stroke in July 1950, just half a year after he retired from his position at Lovisa (Box 1).

BOX 1. VOICES ON ADOLF LICHTENSTEIN

Charlotte Urwitz is a grandchild to Adolf Lichtenstein. She remembers her maternal grandfather as respected and well-liked, both at work and privately, and does not support the notion that he was to have been authoritarian. Her grandfather was perhaps a patriarch—he was strict, knowledgeable and exuded confidence—but he was deeply empathetic. In his clinic, he kept a bowl of gummy raspberries to give to children after an injection or something otherwise unpleasant.

Charlotte recalls how she as a four-year-old experienced her grandfather. He was an adult who looked children in the eyes, joked a little and asked questions of the child instead of the mother. That was very unusual for the times. Therefore, her memories of her grandfather are solely positive. They quite simply liked each other.

For Acta Paediatrica, Charlotte looked through saved obituaries and letters after her grandfather’s passing.2, 3 Following are some voices from those recollections:

He was a personality, such as one seldom has the good fortune to meet. He was at the same time a humane, suffering person who had the ability to be moved to tears, and a strict, fair and straightforward boss, from whom one always knew that one could hear the truth. Towards his colleagues from my country, he was especially warm.

As a practicing paediatrician and family doctor in Stockholm for more than four decades, he has been a dependable rock for worried families and a true friend to children. As the Doctor without comparison will he likely be remembered by most.

From words of remembrance written by later consultant physician in paediatric cardiology in Gothenburg, Associate Professor Lars-Erik Carlgren—who was trained at Crown Princess Lovisa’s Children’s Hospital (Figure 2).

The paediatrician Magnus Lichtenstein is also a grandchild to Adolf (Figure 3). Magnus was only three years old when his paternal grandfather passed away and has no personal memories of him, but he relates the following anecdote that highlights Adolf’s storied strong sense of duty: In July 1950, Adolf went by car from Stockholm to participate in an international paediatric congress in Rome, where he was to lecture. The first stop was, however—according to plan—Marseille. There Adolf met his oldest son Henrik—even he a paediatrician—who had come to Marseille by boat following a paediatric year in the United States. Adolf explained then that he was having symptoms of a cerebral insult, and thereby considered himself unable to participate in the congress. He urged Henrik to represent Swedish paediatrics and him by carrying out the lecture, while Adolf himself intended to return to Stockholm by train (!). This is what occurred.

Adolf actually reached Stockholm, but died from the insult shortly after arrival.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.