Neoliberalism's Imagined Futures: Sustainability as Colonialism in Eco-City Design

Abstract

enThis article examines the architectural tropes used in designs which are concurrently branded as sustainable and futuristic, offering a critique of techno-solutionist architectures that have been promoted by the European Union, World Expos, and forward-looking design pedagogy. Through an analysis of the designs of Belgian architect Vincent Callebaut, I observe that such “eco-futurist” images symbolically communicate an association with sustainability through the visible use of “green” technologies and the adoption of highly contextual encounters with greenery, rhetorically prefaced on the ability of techno-science to mediate human–nature relationships, and visually bound within the design tropes of luxury tourist destinations. By intertwining the aspirational futures of sustainable design with the aesthetic sensibilities of the wealthy, I argue that eco-futurism primarily aligns itself with the interests of neoliberal property development and the spatial and social logics of colonialism.

Résumé

frDans cet article, j'examine certaines caractéristiques de styles architecturaux utilisés dans des projets qualifiés à la fois de durables et futuristes, pour mener une critique des architectures techno-solutionnistes promues par l'Union européenne, les expositions universelles et la pédagogie du design innovant. L'analyse des projets de l'architecte belge Vincent Callebaut révèle notamment que ces images « éco-futuristes » s'associent symboliquement avec la durabilité à travers l'utilisation visible de technologies « vertes », et la mise en scène de rencontres hautement contextuelles avec les éléments de verdure, rhétoriquement basées sur la capacité de la techno-science à servir de médiateur dans les relations entre l'homme et la nature, et visuellement liées aux designs caractéristiques des destinations touristiques de luxe. En conjuguant le design durable de futurs imaginaires avec certains schèmes esthétiques associés au luxe, il apparaît ainsi que l’éco-futurisme s'aligne principalement sur les intérêts du développement immobilier néolibéral comme sur les logiques spatiales et sociales du colonialisme.

Introduction

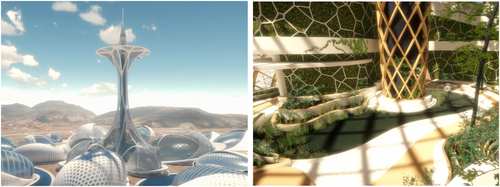

Climate change, exacerbated by the extractivist logics of late capitalism, has prompted neoliberal actors to devise a cornucopia of imagined technological solutions through which the market will resolve the very crises it has created. A techno-optimistic paradigm of “moonshot” startups, buzzword technologies, and digitally rendered projects have established and consolidated the discourses and imaginations through which future technology will inevitably justify continued exploitation of the present. Forward-looking design studios have produced new urban geographies whose sustainable features will, allegedly, not only heal our relationship with nature, but allow for a globalised future of transnational eco-luxury and abundant renewable resources. In this paper, I seek to critically examine such virtual geographies, which I refer to as “eco-futurism” (see Figure 1), as a popular imagination which has dangerously contributed to producing “a normative association between the sustainable and the spectacular” (Avery and Moser 2023:2).

After defining eco-futurism (its primary actors, design tropes, and political economies), I will argue that its environmentalist imagery primarily communicates an aesthetic association with sustainability, which may not necessarily be functionally sustainable, nor feasibly constructable. I argue that the relationship with nature visualised in these renders, expressed through green walls and organic shapes, is one built on highly contextual and fragile encounters with nature, rather than a pluralistic acceptance of natures. In highlighting this, I argue that this contextual allowance for urban nature is bound within the design sensibilities and spatial relationships of wealthy neoliberal elites, and is interwoven with spatial segregations established by colonialism.

In this way, these images, circulated as the aspirational target of urban planning professions by universities, popular media, World Expo organisers, and the European Commission (EC), function as a tool for the “colonization of the future” (Miraftab 2016). They provide an imagination through which continued neoliberal capitalism, and its patterns of extraction, dispossession, and segregation, is positioned as inevitable and environmentally desirable. In doing so, such architectural renders serve to limit the range of possible design and policy interventions available within social imagination to only those which perpetuate continued contemporary injustice. I conclude with a call to reject all aesthetic constructions and crystallisations of the future, and instead highlight the continually present process of resistance against extractive industries.

Defining the Eco-Futurist Aesthetic

While there exists a plurality of imagined sustainable futures, from Paolo Soreli's countercultural “arcologies” to the consumer-oriented New Urbanism movement, I am here focused on one particular aesthetic commonly used to represent speculative eco-urbanism—gathered and organised through designs which are branded as both “sustainable” and “futuristic”, as described in contemporary popular press and internet search. It is an image of the future drawn from a rather vulgar selection of pop-culture ephemera, rarely seen in high science-fiction cinema or literature, but extremely prominent within the visuals of Silicon Valley, sustainable design competitions and press releases, stock photo galleries, pamphlets and conferences on sustainability, video games, and university research programmes (CRAFT 2021; eVolo 2022; Stewart 2018; Webster 2021). I refer to this style as “eco-futurism”, utilising an admittedly colloquial use of “futurism”, separate from 20th century Futurism.

This architectural mode is composed, almost exclusively, out of white computer-generated forms, bending and folding in complex curvilinear and organic shapes, adorned with visually decorative solar panels, wind turbines, and greenery integrated into the walls and/or landscaping. Their forms evoke a sense of futurity by distancing their designs from quotidian architecture, and through the self-consciously digital nature of their shapes, an image of the future only possible through recent advances in engineering. Their white panelling evokes a history of white walls within ecological architecture, which has often purposefully invoked allusions to the spacecraft of the American space programme (Anker 2010).

These designs are the product of several architecture and planning studios that brand themselves concurrently around futurity and sustainability. These include Vincent Callebaut Architectures (whose works will be the central case study of this paper), Laboratory for Visionary Architecture (LAVA), MAD Architects, CAA Architects, Urban+, URB, Ken Yeang, Jacque Fresco, and Jacques Rougerie. Eco-futurist aesthetics have been adopted in projects by major firms, such as Bjarke Ingels Group's (BIG) EuropaCity, Mars Science City, and Masterplanet projects, Zaha Hadid Architects’ (ZHA) Hangzhou International Sports Centre and Chengdu Science Fiction Museum, and Heatherwick Studio's Little Island. The style has been used for numerous vaporous techno-solutionist projects, such as NEOM's ill-considered The Line, and HyperloopTT's station design.

Grouped together, these projects make up a very particular and homogenous spectacle of environmental techno-solutionism. Formally, eco-futurism draws from a set of three related but separate contemporary design practices which claim to utilise advanced engineering to offer environmental benefits or improved energy efficiency. These include: parametricism, which algorithmically generates forms according to inputted parameters, such as required air flow or sunlight, a practice used by ZHA and CAA Architects; biomimicry, which seeks to borrow functional properties from nature to create more sustainable design, used by Vincent Callebaut, LAVA, and Rougerie; and biodomes, those grand bubble-like greenhouses popularised by Buckminster Fuller and Pauly Shore, but which have evolved into more complex geometries and contexts within the last decade, found among Callebaut's works and URB. These advanced engineering practices each claim to optimise design for sustainable urbanism and invoke a techno-optimistic visual rhetoric that sustainability can be attained through the adoption of scientifically produced structures incongruous from what is available within conventional architectural landscapes. The use of organic shapes, either directly derived from nature or parametrically produced, makes a visual argument that future science will offer a social “return to nature” not possible without these advances.

Despite proposals for eco-futurist projects by major studios like BIG and ZHA, they remain on the whole strictly speculative structures—proliferated in phases of fundraising (Rapoport 2014), political mobilisation (Caprotti 2014; Koh et al. 2022; Wade 2019), or merely as inspirational material for entrepreneurial “incubation” (Dobraszczyk 2019; Pérez-Milans 2021); readers should consult this literature on the political economies of speculative architecture for details. In spite of their immateriality, they have been institutionally legitimised through the emergence of awards industries and thinktanks promoting sustainable design (Avery and Moser 2023; Pérez-Milans 2021). They have been taught in architectural pedagogy (see Krivý and Gandy 2023; Pérez-Milans 2021), presented throughout the Dubai Expo 2020, promoted at events and press releases by the European Commission (2021), and imagery of this style has been used by city councils such as the Tokyo Metropolitan Government's “Tokyo Bay eSG Project”. Through their promotion by highly placed public and private actors, they provide imaginations which “motivate real decisions that have distributional consequences”, even if few designs are actually constructed (Beckert 2016:11).

My analysis of this style is centred on the Belgian architect Vincent Callebaut, whose designs most consistently embody the eco-futurist aesthetic. A rather pulp designer, Callebaut's works have never been discussed in serious professional outlets like Detail or The Architectural Review, but make regular appearances in pop magazines Designboom and Inhabitat. While only two of Callebaut's projects have actually been constructed, his designs are extremely visible in online image searches for “green city”, “sustainable city”, and “eco-city”—taking up almost the entirety of results if “future” is added to the query. Despite a seemingly unknown status within professional architectural discourse, he is regularly invited as a keynote speaker for conferences on sustainable urbanism, including the European Union-led 2018 EU Green Week. His studio has received commissions from the EC and Paris City Hall, designed Belgium's pavilion for Expo 2020, and was described by EC representative Gilles Laroche as “the global authority on futuristic and sustainable architecture” (Callebaut 2021a).1 Links to images of Callebaut's projects can be found in the endnotes.2

Using a case study of two representative Callebaut projects, “The Gate”, a planned but uncompleted mixed-use commercial centre in downtown Cairo (Callebaut 2014a), and “Pollinator Park”, a fictional controlled ecosystem for the protection of pollinating bugs commissioned by the EC and made into a VR space by developer Poppins & Wayne (European Commission 2021), the following section will examine how sustainability is symbolically constructed within eco-futurist designs. Establishing this, I will confront how these designs recuperate environmentalist imagery into the inherently unsustainable sensibilities of luxury property development, and discuss how these technocratic and luxury aesthetics are rooted in the logics of colonialism.

Symbolic Sustainability

Vincent Callebaut's eco-futurist projects have been promoted within popular culture as an aspirational future of sustainable technology. Given the keynote presentation of the 2018 EU Green Week, his works were platformed under the year's guiding theme “Green Cities for a Greener Future” (EU Environment 2018). The popular video game Cities: Skylines awards late-game players with a building modelled on Callebaut's “Lilypad” design which removes pollution from the players’ simulated cities.3 Like Don Davis’ and Rick Guidice's imagery of space settlements commissioned by NASA in the 1970s, which would come to influence architecture and science industries throughout the coming decades, eco-futurism is a design “mascot” for the wider techno-financial project of sustainability (Scharmen 2019:339). Its forms mobilise tropes derived from science fiction to create normative associations between environmentalism and imagery already culturally associated as futuristic. In the process, these designs generate new tropes of future-imagery which intuitively implicate the kinds of investments needed to bring society to this future state.

“The Gate”,4 designed for Egyptian client Abraj Misr Urban Development, was planned as a luxury mixed-use office/commercial/residential block made of curved white panelling and floor-to-ceiling glass windows, covered in a complex curvilinear steel curtain adorned with vibrant vertical greenery, solar panelling, and wind turbines, supporting 1,000 “smart” apartments (Callebaut 2014a). The steel mesh solar canopy draped above the complex recalls the megastructural roofs of Buckminster Fuller and Kenzō Tange, updated through Callebaut's use of biomimetic metaphors to represent “the combination of Trees and Building … metamorphosing the city into a vertical, green, dense and hyper-connected ecosystem”, while facades beneath the megastructure utilise “organic shapes inspired by the structure of a coral reef” (Callebaut 2014a). Symmetrically throughout the complex, the steel canopy curves inwards into structural columns of the facility, planned to serve as a windcatcher to passively cool the complex, and as a platform for the flora-adorned green walls. In 2016, Marriott International announced plans to launch its “eco-conscious” brand, Element Hotels, through The Gate project (Marriott International 2016).

Planned to be constructed from 2015 to 2019, the complex was ultimately never built. The project was a massively ambitious and likely expensive proposal. It would have required bespoke steel construction throughout the base and mesh drape, materials and methods atypical of Cairo's established construction sectors. This is a feature typical of eco-futurist studios, who regularly propose radically expensive and complex structures to locales in the Global South where micropolitics of labour and construction make their completion highly improbable (Koh et al. 2022).

The green features of the project are given high visual prominence within its renders, with the white steel design of the base structure serving to highlight the blues and greens of the solar panels and green walls, while the wind turbines are arranged symmetrically upon the rooftop and adjoining boulevard. The building ostensibly serves as a platform for the highly visible use of technologies associated with sustainability. Yet, while the project proposal claims to assure 50% energy saving (Callebaut 2014a), there is no transparently distributed quantitative data on how each of these features will contribute to this, and almost no actually built spaces from which to comparatively measure the efficacy of these designs. Academia and journalism have found numerous examples of projects where such styles served only as a form of greenwashing for developments with vastly negative environmental impacts (Cugurullo 2016; Koch 2014; Koh et al. 2022). Some studies of existing eco-spaces found occasions where hyper-visible infrastructures of sustainable power were not even genuinely connected to their local power grids (Koch 2023; Pow 2018). Indeed, innovations visually associated with sustainability are regularly branded as eco-developments in locations where their deployment actively proves less sustainable than conventional alternatives, such as the use of green space and air-conditioned biodomes in arid countries (Koch 2014). In The Gate's context, the proposal to build luxury apartments adorned with vibrant greenery seems antithetical to sustainability in an arid environment facing water scarcity. Further, such elaborate bespoke design is simply not required to achieve the energy efficiency goals which The Gate had hoped to gain. LEED's (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Platinum certification, which the project had aspired to attain, can be acquired through much more conventional, subtle, or vernacular design (Tabb and Deriven 2014:118), implicating The Gate's environmental features to be more semiotic than scientific. Thus, this style must be approached primarily as a visual one, which might contextually offer energy efficiency gains, but on the whole may only visually signal an intended association with sustainability through the promotion of technologies marketed as sustainable.

This hyper-visibility of sustainable signifiers like unnaturally natural green walls, wind turbines, and solar panels share similarities to the spectacular fetishisation of water and power infrastructures in early modernity, described by Kaika (2005). In her book City of Flows, she notes how the early modern urbanisation of water was accompanied by an aesthetic coding of water infrastructure, given grand spas, fountains, and dams that signalled new social relationships to water and the technologies which enabled its flows. Within The Gate, the visual signifiers of hyper-sustainability create a similar spectacle of “new infrastructures” which would mark society's advancement to a new stage of modernity—visually arguing that humanity has (or soon will have) achieved sustainable resource abundance, whether or not this is true.The natural environment is prominent, but largely unrecognisable. It is presented as artificial and staged. Several aspects of the representations of the natural environment accomplish this. First, the colours are brilliant blues and greens, lit by a bright but unseen sun. The sun is shining, but it cannot be located. Second, nature is presented as uniform. Trees, grass and wildflowers are manicured and appear controlled. Nature is not wild, and it has lost its fractals, nonsymmetrical patterns and variation. Third, shadows or any potential darkness are erased or tightly controlled. There are no other “moods”, varying states of nature or seasons. The setting is always sunny, clear and clean. It never rains. A storm has never passed, leaving droplets or wet roads. It is always the peak of summer … The advertisements allow for the imagination of a future where nature is “better” than it is now.

Kaika (2005) argues that when water is brought into the city it becomes semiotically purified from the chaotic and unhygienic flows of non-urban nature. Similarly, plants within The Gate are visually separated from the messy natural world beyond their landscaped grounds—turned into fetishised symbols of positive “sustainable nature”. One signal that the future will never actually look like these renders, even in the most techno-optimistic imagination, is the fact that if such sustainable abundance were ever achieved, these infrastructures would soon be visually removed from urban spaces, following the history of water infrastructures which were systematically hidden from public society once they had become normalised and commodified (Kaika 2005). Building on this, the following subsection will examine how Callebaut uses colour as a means to frame and fetishise “sustainable nature”, and how the production of this nature is rooted in its technocratic segregation from uncontrolled outer environments.

White Walls, Green Walls: On Colour and Containment

Across Callebaut's works, the eco-futurist city is blindingly white. As light-coloured reflective surfaces can reduce energy consumption in warm climates and mitigate urban heat island effects, there is some justification for this, though this necessity is dependent on geographic context, and other light colours besides white offer similar effects (Radhi et al. 2014). Still, white is the colour of choice for the imagined eco-future regardless of context, even as many of Callebaut's more fictional designs are imagined as enclaves in empty wilderness, where there would certainly be no urban heat islands. Rather, the regular adoption of white in these projects should be viewed as a socially communicative one, serving a specific cultural function when placed among greenery and dirt.

There is a long history of whiteness in forward-looking architectures. Popular representations of white walls in early modernism established a recognisable look for the avant-garde (Wigley 1995:303). Apple formed a design ethos tying fluid whiteness with enlightened consumerism (Moore 2017:48). White is the colour of lab coats, science museums, research facilities, and technologies of the future. The early eco-city project Biosphere 2 was painted white, as one of many visual and rhetorical associations to the US space programme, and the Eden Project in Cornwall continued this aesthetic (Anker 2010:122–123). Contemporary architects like Santiago Calatrava and ZHA utilise whiteness to emphasise design as an art of pure engineering form (Frampton 1999). Their implicit techno-optimism is captured palpably in the viral 2023 TikTok parody of 1990s techno-culture “Planet of the Bass”, where Calatrava's World Trade Center Station seems a naturally fitting locale for vapid lyrics of “cyber system overload, everybody movement” (Gordon 2023).

Callebaut's Pollinator Park continues in this tradition (see Figure 2). The project was designed for the EC as an awareness-raising initiative towards the impact of climate change on pollinating bugs, depicting a future where human activity has led to the near-extinction of pollinators, necessitating the construction of a controlled enclave for their remaining numbers. The design was adapted into a VR experience where the user may navigate through the facility and collect fictional diary entries which detail a narrative of the complex's inspiration and construction. Following Callebaut's interest in biomimetic design, the structure resembles the reproductive morphology of flowers, centred around a pollinating stem, and blooming outward at the base into a series of curvilinear biodomes.

Following the history of whiteness in design, the white plastic biodomes of Callebaut's building, utterly alien to the landscape around them, provide a performance of technocratic environmental control, removed from messy and fallible human intervention. In the VR experience, the climate-regulated farms and construction show no signs of labour, seemingly entirely automated and self-sufficient. The biomimetic design alleges to harmoniously derive its forms from nature rather than human culture—“in an act of apparent humility towards nature, architecture stages the effacement of itself (appearing to dissolve into biology)” (Krivý and Gandy 2023:1060). Its biodomes follow the common sci-fi trope where automated systems and sophisticated greenhouses protect nature from humanity's faults, famously articulated in the 1972 film Silent Running. This rhetoric is upheld within the VR experience, where the facility seems eerily deprived of human company. The VR tour is guided by an automated disembodied voice, and the collectable diary entries which elaborate on its construction and inspiration are reminiscent of the interactive storytelling used in games of societal collapse like Fallout (1997–2018) and Bioshock (2007).

Within a narrative of future environmental collapse, these techno-scientific biodomes built to protect pollinators articulate “the sense that nature itself is so delicate and fragile as to be in desperate need of technological protection for the sake of our own survival” (Murphy 2016:210, quoted in McNeill 2022:232). The sci-fi image of a techno-society caring for plants under complex domes presents this structured relationship with nature as a necessary mediator between green spaces and citizens. Like white lab coats, white biodome architecture makes an authoritative claim over the control of space—one based more in visuals than in merit, for as Lockhart and Marvin (2019) have observed, controlled microclimates are often worse for organic life than the open environment.

Biomimetic designers claim to promote a more harmonious and sustainable relationship between humans and nature by accepting organic forms into constructed interiors. However, as others have criticised of biomimicry, this proposed relationship with nature is one fraught with problematic ontologies of nature/culture divides, and regularly views nature not as holding inherent ecological value, but as a source to be scientifically mined, enclosed, and perfected for anthropocentric capitalisation of knowledge and utility (Davidov 2021; Goldstein and Johnson 2015; Johnson and Goldstein 2015; Krivý and Gandy 2023).

This enclosure of protected natures away from messy human living seen in Pollinator Park is structured through whiteness, and the histories of whiteness in ecological and scientific architecture. White curvilinear surfaces, like toilets, bathtubs, and sinks, culturally contain and control nature, allowing a place for matter which would otherwise remain unacceptably “out of place” (Douglas 1984). The green spaces shown in the images of both Pollinator Park and The Gate never include pests, unmanaged landscaping, rough weather, dirt, faeces, mould, rust, or mildew. Instead, as articulated above, they support only hyperreal natures—ever verdant, and structurally relegated into their positions upon green walls, enclosed greenhouses, and between delineated pathways. As I will elaborate in the next section, despite the prevalence of symbols associated with environmentalism, coexistence between humans and nature in eco-futurism is not made socially acceptable, but contextually palatable.

Constructing a Palate for Nature: Eco-Futurism and Luxury Design

The contextual allowance for natural matter into the architectural envelope, the feature which most singularly communicates eco-futurists’ interest in environmental sustainability, is premised on the adoption of decorative flora placed only where their intrusion falls within the design sensibilities of the upper class. Callebaut's renders, as seen on his studio's website,5 abound with imagery derived from the promotional materials of transnational luxury tourism. His renders depict yachts, private patios, boutique cafes, extravagant views, bespoke lounge furniture, decorative statues, elegant dining terraces, and delineated pathways for strolling. Indeed, Marriott International had planned to open its eco-hotel brand within The Gate, placed alongside the facility's planned shopping malls and infinity pools.6 Callebaut's single completed permanent structure, the Tao Zhu Yin Yuan tower in Taipei, is a luxury apartment complex commissioned by petrochemical mogul, Shen Ching-jing, chairman of Core Pacific Group, which includes China Petrochemical Development Corp as a subsidiary (Callebaut 2021b; Jennings 2018). In the spirit of biomimicry, the enclave's perimeter is described as taking “inspiration from the enchanting beauty of a sahā forest”, while “security rooms on both sides of the main entrance ensure the highest levels of security and privacy” (Tao Zhu Yin Yuan 2023). Its apartments are estimated to start at US$65 million (Strong 2017).

Within the sensibilities of luxury design, nature is allowed only when its forms can be harnessed into unobtrusive decorations. In Callebaut's renders, organic life is integrated into structures only where their presence does not interrupt the human use of the space for recreation, labour, or consumption. Greenery is placed vertically upon the walls or hanging above the space, so as not to obstruct mobility. The hyperreal natures presented in these images appear displaced from the labour required in maintaining plant life. The placement of greenery high above the floor in these designs implies the automation of their irrigation, separated from physical encounters with plant life required in gardening—at least for the paying residents of these spaces. As a means to resolve human–nature relations through more frequent encounters with nature—a means to “heal our relationship with nature” as one EC representative describes of Pollinator Park (Callebaut 2021a)—allowing nature to be included only as a luxury decoration appears woefully insufficient. To accept natures only where they do not obstruct the function of capital does nothing for those natures whose unmolested presence does interfere with the interests of the eco-luxury development and engineering industries, such as the landscapes of often indigenous-occupied territories, rich in the minerals required for solar panel and wind turbine development (Dunlap and Laratte 2022; Owen et al. 2023).

Green walls, like those adorning The Gate, represent an attempt to increase interactions with nature while maintaining the logic of commercial property development, allowing a selective integration of plants with consumption and land development. While rural expanses of green space are being increasingly enclosed by wealthy elite (Farrell 2020), urban microspaces of nature have proliferated to offer interactions with greenery mediated by consumerism and flexible labour. The Gate's vertical greenery displays nature within an Enlightenment logic of upwards development. Rather than the negation of urban space in the production and management of public parks, green walls rise upwards through concrete and steel, like the financial towers of late capitalism.

While many eco-futurist projects like The Gate are designed as spaces for construction in the Global South, media promotion of these designs appears produced specifically for the tastes and interests of wealthy Anglophone audiences rather than local demographics, often circulated within English-language press releases (see Marriott International 2016). Several of Callebaut's more self-consciously fictional designs, like Pollinator Park, or floating manmade islands planned to house climate refugees, invoke an aspirational future where advances in efficient sustainable development provides spaces of abundance within a more egalitarian and inclusive future. Yet, this optimistic imagination is represented as one which only accommodates the visual culture of transnational techno-luxury, and where spaces are designed to incorporate only the behaviours socially accepted by the upper classes. Ultimately, in the regular adoption of luxury signifiers, these designs are marketed specifically to the transnational elite—imaginations of potential global luxury hotels and US$65 million apartments not meant for local populations, but to broaden the globe-trotting locations of the Learjet class and their environmentally self-conscious oil barons.

For Spencer, these forms function as the spatial articulation of free market theory, where continuous surfaces position individuals as heterogenous free agents in a porous semi-natural space that alleges to equally accommodate consumer difference, but which in reality only accommodates wealth. While these architectures visually imply the lightweight “flexibility” of neoliberal “creative economies”, they are in fact deeply inflexible, dependent on constant expensive maintenance and too specific in their engineering to allow for spaces to be easily repurposed (let alone, redesigned) for future uses or inhabitants. Infrastructures which reveal the consumption of resources or the labour of maintenance are hidden away, presenting only a sensuous affectual present, where enterprising individuals face no boundaries or overt structural rhetoric imposed upon them, free to partake in experiences advertised on luxury travel brochures. In these superficial spatial freedoms and selective acceptance of urban natures, they present neoliberal property development as the self-evident natural order, to which “there is no alternative”, having in this predetermined future to have successfully overcome changes in climate which would contradict neoliberalism's continued ability to dominate and dispossess.The architecture is fluid. Its forms materialize out of thin air or extrude themselves into existence. The pleats, grilles and apertures patterning their surfaces seemingly subject to the same unseen forces. There are no signs of labour. Threaded between the buildings and pathways, sometimes woven into the architectural envelope, are the green spaces that signal sustainability, deference to the laws of nature.

This rhetoric is expounded in the fictional diary entries of the Pollinator Park VR experience. Despite emphasis on the scale of the climate crisis, that if left unchecked would allegedly necessitate a constructed enclave for bug life by 2050, the EC project offers no specific political positions or policy recommendations, but instead describes a group of benevolent “business angels”, presented in one diary entry as the “Interdisciplinary Guardians of Planet Earth”, funding a singular introverted genius scientist as a means to protect pollinators (European Commission 2021). In doing so, the EC aligns its political platform with the interests of the neoliberal market, rather than the political inclusion of its residents.

Such images of the future, promoted by actors like the EC, are further established and consolidated within social imagination by an apparatus of financial media and popular culture which frame these eco-fantasies as an already existing inevitability. While I have found no evidence that construction of The Gate ever broke ground before its cancellation, this did not stop Forbes, Business Insider, and the World Economic Forum from reporting on the project as if it were actively “going up”, “Soon-To-Be”, and “to open”—each repeating the same press-release details without confirmation of actual construction progress (Garfield 2017a, 2017b; Tablang 2015).

Regularly, such improbable digital renders as The Gate are circulated in popular press and university ephemera as signs that a green future is nearing, just around the corner to “help curtail mankind's alarmingly high levels of energy and water consumption”, as Forbes’ coverage puts it (Tablang 2015). As Avery and Moser (2023) observe, press releases touting sustainability awards won for imagined projects abound, while no media circulates when these goals are never reached. While in development, The Gate was awarded LEED's Gold Plus precertification, a status LEED advertises specifically for PR purposes, so developers can “market the unique and valuable green features of your project to attract tenants and financiers” (LEED 2022), such as was accomplished in attracting Marriott to the project. In Forbes’ promotion of the project, this “precertification” state is even dropped entirely, such that the non-existent building is claimed to have acquired full Gold Plus certification (Tablang 2015).

By establishing a normative association between sustainability and the sensibilities of the wealthy, eco-futurist design tropes, proliferated in EU-funded conferences and promoted in university environments (EU Environment 2018; Krivý and Gandy 2023), have produced design pedagogies and practices that profess to establish best practices for reducing climate change, but which instead primarily prepare designers and planners for the interests of the luxury real estate industry. As expressed by Miraftab (2016), “Planning as a profession praises itself for serving the public good but professional planners often find themselves in the service of private good”.

The Colonial Geographies of Techno-Sustainability

By intertwining sustainability with the lifestyles of the wealthy, the spatial relationships of eco-futurism are inherently rooted in histories of colonialism—both in the production of controlled enclaves protected against unmanaged wilderness, and in the strategic use of environmental conservation as a tool of colonial dispossession.

The use of advanced computer-generated forms like biomimicry presents a performative rejection of the local cultural histories where projects are planned to be constructed, presenting a rhetoric that environmental protection is dependent on the technocratic adoption of scientifically optimised engineering rather than cultural continuity. The Gate shares little resemblance to existing geographies within Cairo, proposed like other “iconic” world-city destination projects which seek to adopt materials and styles attractive to cosmopolitan consumers, conscious of climate change but disinterested in regional design histories (see Kaika 2011; Knox and Pain 2010; Samalavičius 2020). Spaces of eco-futurism like Pollinator Park are presented as “self-generative, self-propelling and immune from human agency” even as it is acknowledged that these projects would be commissioned by capital-harbouring business angels and ideological investors (Kaminer et al. 2011:14). In this performed renunciation of local cultures for the sake of technocratically managed micro-climates, Callebaut's proposals take on a distinctly colonial attitude towards its geographies, as spaces to be corrected through acultural scientific interventions.

Callebaut's white monoliths are regularly visualised within foreign geographies presented as empty landscapes awaiting civilisation. His project “Paris 2050”7 takes steps to integrate his megastructures within the existing geography, presenting the plan as a guided walk from Notre Dame to Gare du Nord (Callebaut 2014b), yet his designs for Cairo (The Gate) and Delhi (Hypérions) are represented as entirely abstracted from their settings,8 utilising placeholder structures for the surrounding apartments or simply verdant greenery as far as the eye can see. The technocratic position which justifies building structures for the sake of nature rather than human culture is undermined by Callebaut's equal disinterest in capturing the existing natural geographies of his projects, as the biomimetic design of his Delhi project is based on Sequoia sempervirens, a Northern Californian tree which does not exist in India (Callebaut 2015).

As Frantz Fanon argued, colonisation is built on intrusions wherein the rejection of local culture is presented as a necessary and benevolent intervention. Fanon (1986:18) writes of the colonised as “every people in whose soul an inferiority complex has been created by the death and burial of its local cultural originality”. Technocratic design, embedded within the tropes of luxury real estate, seeks to establish a cultural paradigm for the demographics most at risk of climate disasters, who are presented with an image of the future in which the renunciation of local culture, and the continued accommodation of space, resources, and labour to transnational neoliberal economies, will both protect against climate disasters and bring forth the comfort that the Global North has received through their own continued exploitation. As such, utopian futuristic projects like The Gate have been regularly produced for, and commissioned by, municipalities in the Global South, such as Malaysia's Forest City, Indonesia's Nusantara and Great Garuda projects, and Kenya's Konza Technopolis (see Koh et al. 2022; Wade 2019; Watson 2014).

Through a technocratic apparatus that claims environmental protection requires the adoption of advanced, contemporarily stylish geometries which are entirely foreign to existing regional architecture, eco-futurism platforms a rhetoric that nature must be shielded from existing human cultural ego, while harbouring a “crypto-political dimension … as it smoothly aligns itself with the power of a neoliberal political economy of urban growth that has been characterised by an antipublic agenda, engendering unprecedented urban asymmetry and socioeconomic inequality today” (Cruz 2015:190).… the total result looked for by colonial domination was indeed to convince the natives that colonialism came to lighten their darkness. The effect consciously sought by colonialism was to drive into the natives’ heads the idea that if the settlers were to leave, they would at once fall back into barbarism, degradation, and bestiality.

Eco-futurist designs are often proposed with a rhetoric of lofty benevolence for ecosystems and societies facing precarity. Callebaut had proposed multiple projects as solutions for climate refugees. Another studio, CAA Architects (2018), proposed a futuristic luxury structure as protection against rising seas in the Maldives. Absent in all these examples are voices from the populations which eco-futurists claim to help—those who are so regularly excluded or displaced from present-day luxury development.

In a recent study, Garcia-Arcicollar (2024) conducted an ethnography of students in the Maldives facing climate-based precarity. In her methodology, she asked local populations to draw their own imagined futures for the country. The results differ substantially from the digital cultures of eco-futurism. Instead of high-tech biomimicry, the artworks emphasise giving space for natural resources like mangroves and coral reefs to maintain the islands. The buildings students drew remain restrained and conventional structures, aided with greener but realistic technologies like solar panels. The drawings suggest a view of the future not mediated through science fiction media, computer-aided design, or the aesthetics of transnational luxury tourism, but instead an aspiration for a continuity of the local community's own sociocultural-geographic relations. It is not the imagined global residents of the future who are in need of environmental and social protection, but the actual human and non-human populations who live there now.

Conclusion: Resisting the Future

In this paper, I have argued that techno-utopian images of sustainable architecture produce a normative association between the sustainable and the spectacular, based on a belief in the ability of techno-science to mediate human–nature relationships. Through the designs of Vincent Callebaut, we may observe that this technocratic imagination seeks to maintain the natural environment through the allowance of highly contextual encounters with nature inside architectural spaces—accepting nature only where it is considered aesthetically appealing for an upper-class audience attracted to the design tropes of luxury tourism. By intertwining the aspirational practices of sustainable development with the sensibilities of luxury consumption, the eco-futurist genre smoothly aligns itself with the interests of neoliberal property development, and casually continues the spatial logics of colonialism. As an imagination promoted by World Expos and the EU, it embeds a colonial complex into the minds of designers, establishing a rhetoric that positive reactions to climate change are incongruous with the temporal continuities and geographies of existing communities, dependent instead on the imposition of computer-generated forms and the wealth of technocrats.

This is a future we must reject. Eco-futurism is a colonial imagination following the worst impulses of a culture of technocrats who see their designs as the benevolent fix to worldwide problems which they have largely been complicit in creating. As previously mentioned, Callebaut's single completed permanent structure, the Tao Zhu Yin Yuan tower, was commissioned by a petrochemical baron, with apartments starting at US$65 million. Rather than eco-futurism's promised science-fiction, where advanced architecture gives back to society and the environment through scientifically controlled ecology, Callebaut has created a luxury apartment complex for petrol billionaires to relax above and away from the world which they are actively harming, protected by a biomimetic perimeter of security guards, while their firms produce more precarity for the rest of the world. While proliferating a promised vision that someday the wealthy will benevolently fix the climate through pure engineering, Callebaut, who the EC had called “the global authority on futuristic and sustainable architecture”, has instead provided comfort and protection to the very people who continue to exploit the world at rates far exceeding what few “carbon-recycling” balcony trees were planted on this US$500 million enclave. Cities are increasingly reducing green space as urban property values rise and cityscapes sprawl (Lantz et al. 2021; Pauli et al. 2020). In their stead, eco-futurism has offered green walls on shopping malls, and enclaves protected by armed guards. While there is a plurality of discursive structures through which inequality is justified through environmentalism (Apostolopoulou and Adams 2014; Debert and Le Billon 2024), the eco-futurist aesthetic provides a visual argument for the fragile separation of humans from nature, and the consolidation of natural space into the hands of technocrats. The “glimpse into the future” offered by the Tao Zhu Yin Yuan tower is one which seeks to embed a dependence on neoliberalism to segregate nature from poverty (Callebaut 2021b).

The proliferation of these imaginations within the design academy, STEM pedagogies, and EU outreach programmes professes to prepare students to create forward-thinking solutions to climate change, but in practice is preparing them for luxury real estate industries. These political and educational institutions thus play an active role in the continued consolidation of resources, space, labour, and cultural imagination to wealthy neoliberal actors. As Schwartz (2022:1653) frames it, these imaginations are “redistributing resources … from the citizens of the present to the future”. In contrast, educators and policymakers must seek solutions beyond the promotion of “green innovation” and critically engage with the political and economic systems which concurrently produce colonialism and ecological destruction, while cloaked in the language of benevolence. Designers, educators, and activists must look beyond the development of high-tech enclosures and the resources offered by allying with the elite, and instead engage with a politics of opposition, environmental justice, and care centred on existing residents and geographies.

The eco-futurist city is only one aesthetic visualised to direct lives, resources, and wealth. There are, have been, and will be others, and while I call on educators and conference organisers to avoid, or critically engage with, these imagined futures, it is necessary to pre-empt and reject whatever next paradigm is used to justify the unequal restructuring of society. Creating a world where nature is inherently ecologically valuable, where sustainability is not interwoven with real estate speculation and exploitation, requires a rejection of futurity. In the language of Deleuze and Guattari (1983:381), resistance must be “no more behind than ahead”, but a continuing process “that is always and already complete as it proceeds, and as long as it proceeds”. More socially and environmentally equitable geographies will not be digitally rendered in far off futures awaiting their materialisation, but in the continual process of resistance against the power structures who seek to create uneven futures on our behalf.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Nathalie Pascaru and Greet De Block for their helpful discussions about this suject, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.