“Captains of the Sands”: Urban Illicit Ecologies and Sandscapes in Rio de Janeiro

Abstract

enUrban Political Ecology (UPE) has explored human–soil relations, emphasising the political dimensions of environmental degradation in and through urbanisation. However, UPE lacks critical reflection on governance collusions with illicit actors. Bridging this gap, my paper combines UPE with literature on criminal urban governance, focusing on how urban sand shapes illicit urbanisation. To address UPE's oversight of criminal governance, I explore Rio de Janeiro's militias expanding their illegal portfolio through terrain modification, linking illicit activities to territorial control. Integrating criminal governance with UPE, I argue for the concept of Urban Illicit Ecologies (UIE). Urban sandscapes become multi-sited, illicit geographies revealing imbrications of formal state and criminal actors, political dimensions, and inequalities in resource extraction and environmental processes. By understanding urban illicit ecology, we gain insights into the contested claims of political authority and territorial control between militias and the state.

Resumo

ptA Urban Political Ecology (UPE) explora as relações entre o ser human e o solo, enfatizando as dimensões políticas da degradação ambiental na urbanização e por meio dela. No entanto, a UPE carece de uma reflexão crítica sobre os conluios de governança com atores ilícitos. Para preencher essa lacuna, meu artigo combina a UPE com a literatura sobre governança urbana criminosa, concentrando-se em como a areia urbana molda a urbanização ilícita. Para abordar a supervisão da UPE sobre a governança criminal, exploro as milícias do Rio de Janeiro expandindo seu portfólio ilegal por meio da modificação do terreno, vinculando atividades ilícitas ao controle territorial. Integrando a governança criminal com a UPE, proponho o conceito de Urban Illicit Ecology (UIE). As paisagens de areias urbanas tornam-se geografias ilícitas em vários locais, revelando imbricações de atores formais estatais e criminosos, dimensões políticas e desigualdades na extração de recursos e nos processos ambientais. Ao compreender a Urban Illicit Ecology, obtemos insights sobre as reivindicações contestadas de autoridade política e controle territorial entre as milícias e o Estado.

Introduction: Capitães de Areia

In Jorge Amado's novel Capitães de Areia, the so-called “captains of the sand” confound the social order of Salvador, the capital of the Brazilian state of Bahia. Mostly illiterate and impoverished orphans, they perform their illegal activities, such as burglaries and robberies, in Salvador's wealthier districts. Published in 1937, the story depicts the gang members as victims of a discriminatory, disciplinarian stigmatisation of black, poor urban men (Amado 1937). While the youngsters inhabit the very edges of the urban peninsula, its beaches, they expand their control beyond the sandy terrain, astutely escaping the eye of the police and the state's reformatory institutions. The sandy terrain between All Saints Bay and the city can be read as a metaphoric place that stands for the unstable, violent, and exclusionary ground on which Brazilian cities are being built.

Amado ties Brazil's urbanisation to both illicit activities and social exclusion, locating the urban poor on the sandy rural–urban fringes. Doing so, the novel is an emblematic case for widespread representations of urban fringes in Brazil: on the one hand, fringes are depicted as spaces of picturesque nature, between forest, lagoons, and the sea (da Silva and da Silva 2017), yet to be urbanised and subject to “hygienisation” efforts (Garmany and Richmond 2020); on the other hand, as spaces at the margins of state power (Das and Poole 2004) where clientelist liaisons and transversal logics of urban development between formal governments and strongmen flourish (Caldeira 2017; Coates and Nygren 2020) and urban infrastructures and planning meet securitisation and pacification policing (Cavalcanti 2013). The governance of urban geologies has thus long been linked to questions of displacement and contested authority, yet, as I argue here, urban terrain, at once political and material, merits considerably more critical attention in these debates.

Switching sites to Rio de Janeiro: Flavio Bolsonaro, oldest son of Brazil's former president Jair Bolsonaro, and senator in Rio de Janeiro (PL, Liberal Party), embezzled public funds for investment into real-estate developments in Muzema, a low-income residential area in Rio de Janeiro's west (The Intercept 2020). He supported the illegal, unlicensed construction of condominiums for low-income clients, directed by “militias”, local racketeers. Not only has the case of Muzema received highest public attention when two of the militia-constructed condominiums collapsed in 2019, killing 24 inhabitants; it is also said that leftist politician Marielle Franco's engagement in uncovering the close linkages between criminal actors and government officials in value generation in that area had led to her politically motivated murder in 2018.

Public attentiveness to such militia urbanism is growing. Militia groups have been reported to be strongly invested in illegal sand extraction, a much necessitated and lucrative building material, whose inadequate use has been inarguably culprit to the Muzema building collapses (Monteiro and Nascimento 2023). Analysing militia-authored urbanism in Rio de Janeiro not only allows one to speak of a new scheme of illicit practices tied-up with urban development (Benmergui and Gonçalves 2019), but also about the state's involvement in illicit actors’ disposal over the civil construction sector and related extractive industries that substantiate “state violence” in urban Brazil (Alves 2015), ultimately perpetuating racialised and gendered violence whose underlying genealogies of control and vigilantism are deeply rooted in Brazil's history (Hutta 2022; Souza Alves 2003).

Militias are not opponents to the state, but rather benefit from personal ties with formal institutions. Deploying illegitimate use of violence to enlarge exclusive profit-making value chains, militias are far from being a new actor on stage. Research on militias has shown that their roots do not just lie in the death squads employed during Brazil's dictatorship (Telles and Safatle 2010), but go back to the colonial and imperial eras. Militias are thus consecutive to what has been discussed as donos (owners) of the morros (hills)—a geological metaphor for socially, politically, economically, and spatially segregated peripheries in the city (Birman and Pierobon 2021).

Analysing militia–state collaboration in urban development unveils deep-seated inequalities. Despite constitutional efforts to institutionalise social movement claims, Brazilian cities, including Rio de Janeiro, remain spatially divided (Friendly 2013). Historical urban planning exacerbates divisions between rich and poor, white and black, asphalt and hill (Vargas 2006). Mayor Pereira Passos, in the early 20th century, intensified socio-spatial segregation by flattening hills and draining swamps in the name of hygiene and beautification (Benchimol 1992). The enduring distinctions between morro (hill) and asfalto (asphalt) persist, shaping social inequalities and fuelling violence (Glebbeek and Koonings 2016). This dichotomy also perpetuates disparities in urban development, influencing unequal access to public goods, citizenship, and economic opportunities, segregating experiences of shantytown residents from those in the formal city.

Urban inequality in Brazil is intricately linked to geological conditions. The early 20th century urban reforms under Perreira Passos displaced low-income communities to settle in inner-city hillside favelas or swampy fringes like Maré, Baixada Fluminense, and Barra da Tijuca (Herzog 2013). Coupled with the “unordered urban sprawl” and insufficient planning characterising Brazilian cities since the 1960s (Carvalho 2013:68), these geo-social dynamics yield severe social and environmental consequences. Unstable ground poses socio-ecological challenges, exposing people and nature to threats like flooding, landslides, fires, mosquito-transmitted diseases, and water pollution in swampy areas (Saito et al. 2019). Simultaneously socio-political, the legal ambiguity of “uninhabitable” lands enables illicit actors to exploit growing land demand, thriving in officially declared “risk areas” where formal construction is prohibited.

My paper wishes to contribute to these debates by focusing on the territorial expansion of Rio de Janeiro's militias. The active involvement of militias in urbanisation has received growing academic attention (Araujo 2019; Pierobon 2021) as they dominate a significant share of western and northern territories of Rio de Janeiro's metropolitan area. They are entrepreneurs with economic bases in different urban service markets, intimidating and often violently repressing local businesses and residents through protection rackets with a hierarchical gang-like structure (Araujo and Petti 2022; Hirata et al. 2022). The most important tie of militias with formal politics is through their influence in elections, either by participating in the selection of candidates or by channelling the votes of those who live under their dominance to the most favourable candidate (JDB 2018). Having emerged as counterparts to drug traffickers, militias even have often been welcomed as order-making agents to contain illicit markets (Manso 2020).

Applying a geological lens to the study of militias reveals their deep integration into urban inequalities, shaping urban development logics. Advancing a material turn in studies on urban governance arrangements (Baud et al. 2021), I view urban terrain as a foundational “political materiality of cities” (Pilo’ and Jaffe 2020). The failure in civil construction extends beyond a weakly monitoring state to include the agentic qualities of geological “matters of concern” (Latour 2005), like sand and rubble. Urban grounds aren't mere objects of regulation but are part of broader social and political structures. Sand's relational quality underscores the need to focus on human interventions such as mining and extraction within the political realm. Expanding on Kothari's (2021) “sandscape”, I explore connections among people, places, temporalities, and elements, intertwining ecological, environmental, and political processes.

Sand is not a neutral artefact, not only a commodity, or a scarce resource; sand can be a “geologised” starting point to examine the inequality, conflicts, and negotiations that underlie urbanisation (Dawson 2021). Due to its scarcity in its legal form and the limited policing of its extraction (see details below), sand also gives rise to illicit activities. I therefore suggest that Urban Political Ecology (UPE) also focus on the illicit dynamics that are inherent to processes of capitalist valorisation of urban space. This allows one to look at sand, similar to urban materialities more generally, not as a mere object of commodification but as an element in larger socio-material, licit-illicit environments. The intersecting forces of sand, gravel, and water, of firm ground and fluid bodies, permeate governance arrangements which in turn shape the formation of (un)inhabitable land and construction at Rio de Janeiro's urban fringes. I call this political–material intersection the urban sandscape.

The following will examine the role of militias in expanding their economic and political project in Rio de Janeiro's urban sandscapes. These urban sandscapes connect city-building, including the construction of residential buildings, resettlement of low-income populations from risk areas to social housing developments, and illegal sand mining in Rio de Janeiro's Baixada Fluminense. Before delving further into this, I will, firstly, situate the concept of urban sandscapes at the intersection of literatures on criminal governance and UPE; secondly, expand on debates around sand mining mafias worldwide; and finally, turning to specific sites of urban sandscapes, I will lay out how sand has been a material for illicit city building and moulding of unstable urban grounds on the city's margins.

Urban Political Ecology and Criminal Governance

UPE approaches have addressed the governance of human–soil relations (Heynen 2014; Swyngedouw and Kaika 2003; Van Sant et al. 2021), calling for analyses of how sand is articulated through claims to territorial sovereignty, particularly through the “consolidation of sand into solid ground and the conversion of water into land” (Jamieson 2021:278). Such a call meets UPE's concern with the commodification of natural resources, motivating scholars also to look at the affective values ascribed and sensitised in human–landscape–sand relations (Kothari 2021). These debates provide strong contributions to human geographers’ work on linking physical and human aspects of terrain (Elden 2021; Gordillo 2023; Peters 2021). UPE therefore sides with the latest moves in geographical disciplines to materialise human geography and politicise geology (Yusoff 2018); yet the way in which political institutions and processes and territorial expressions of sovereignty and authority are contested in and through the modification of “nature” lacks a stronger criticism of stateness, governance, and the constitution of power relations through territorial shifts. Exploring how urban sand is a conditioned-conditioning matter of concern within illicit urbanisation I address this possible link.

Criminal governance is entwined with conflicting claims to urban sovereignty, not an alternative control method (Ferreira and Gonçalves 2022; Lessing and Denyer Willis 2019). Criminal groups, such as factions, militias, gangs, and maras, establish connections with state officials, often involving corrupt transactions, notably in areas like favelas and social housing developments (ISER 2018). Local criminal organisations typically wield significant authority, surpassing the state, imposing rules on civilians, and influencing civic aspects like community engagement, voting, work, and access to public benefits (Gutierrez and Delgado Mejía 2022; Lessing 2021). In the case of Rio de Janeiro's militias, they set and enforce rules, provide security, and offer basic services in urban areas, integrating with informal settlements or neighbourhoods (Sampaio 2019, 2021).

Militias wield power by demanding loyalties, operating protection rackets, and either challenging or collaborating with the state's monopoly on violence. This perpetuates violent frameworks, particularly affecting marginalised communities (Arias 2013; Misse 2018). Positioned between formal security forces and private vigilantes, militias form part of a “hybrid state” (Jaffe 2013), suggesting an acknowledgement of their dual everyday presence in serving business and political interests for various actors as a formation of contested sovereignty (Stepputat 2015). Militias now hold sway over a significant portion of the electorate. They extend their influence into illicit urban domains, reshaping aspirations for resilient, just, and democratic community structures in urban peripheries (Araujo 2019; Denyer Willis and Davis 2021; Müller 2021a, 2023). Marginalised populations navigate interactions with both licit and illicit state-like entities (Richmond 2019), with militias emerging as oppressive alternatives to state actors, compelling reliance on their “services” and expanding territorial control.

Yet, while criminal governance literatures often deploy the terminology of territory or territoriality, they remain limited to an understanding of it as area—a quantifiable and mappable expansion of land. Current public perception identifies “militias” as primary occupants of urban territory in Rio de Janeiro's metropolitan areas, exerting influence over most of the population. The expansion of militias is the key phenomenon shaping armed conflicts in the Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro, particularly concentrated in the municipality of Rio and the Baixada Fluminense (BF) (Hirata et al. 2022). However, as they are increasingly linked to illegal land invasions and land-related activities like cleansing or grabbing (grilagem), I sense a need to analyse their activities in terms of the terrain-shaping activities and how these are sustaining territorial control.

To explore these illicit geographies further, I suggest combining a perspective on criminal governance with one on urban ecologies: As a field, Urban Political Ecology studies the political embeddedness of natural resources and grounds, theorising cities as manifestations of both social and natural environments (Gabriel 2014; Heynen et al. 2006). By “natural”, UPE commonly refers to a process which is always already part of (intentional) modification, commodification, and human capitalist “production” (Smith 1984). UPE conceptualises landscapes and urban infrastructures of cities as historical materialisations of the interaction between humans and nature in the production of landscapes (Wolf 1972). In addition to the work of actor-network theorists (Castree 2002), UPE often builds on critical Marxist, postcolonial, feminist, and anarchist traditions (Loftus 2019). As such, UPE aims at criticising and countering injustices, inequalities, and exclusions that are the product of capitalist appropriations of nature, class- and gender-based and/or racial disruptions.

Scholars investigating these disruptions have linked the study of non-state armed actors contesting the state's territorial sovereignty to their volatile attempts to invest in resource extraction and demonstrated that organised crime, private and state actors are co-dependent on the building of infrastructures to foster their political economies (Peñaranda Currie et al. 2021). Recent political ecology attempts to relate (state) violence and resources, extraction, climate change, and shifting geologies (Escalona Ulloa and Barton 2020) have clearly demonstrated the importance to further study the socio-material links between cities, state violence, and other-than-state violence. Critical UPE scholars have also demonstrated the need to look at cities as sites for emancipatory projects that reject and actively counter discriminating (state) projects (Ranganathan and Balazs 2015).

As capitalist expansion and urbanisation occur via diverse forms of violence—including war-making and forms of violence implemented by the organised crime in and through resource extraction and related profit-making activities—UPE holds analytical potential to make sense of how the shifting arrangements of power correlate with urban environments. However, so far, UPE has missed out on criminal governance, demanding a closer look into the historically situated, and often unjust, collusions of heterogeneous authorities involved in urbanisation. Thus, the theoretical objective of this paper consists in rethinking the relationship between urban grounds and criminal governance. I situate the exploration of this relationship in recent attempts of Rio de Janeiro's militias to expand their illegal portfolio, moulding and then benefitting from the terrain's conditions. I allude to a more-than-physical meaning of terrain, as also a political space, offering opportunities for illegal actors to diversify their portfolio and thus further destabilise the political terrain of RJ's periphery. Urban sandscapes are such physical-political terrain.

My conceptualisation of urban sandscapes is influenced primarily by the notion of “patchy landscapes” introduced by Tsing et al. (2019). Aligned with critical perspectives on the Anthropocene, these authors emphasise the importance of scrutinising the inequalities inherent in this epoch. Their focus on the potent influence of shaping landscapes during the colonial-capitalist era underscores their interest in “the uneven conditions of more-than-human livability in landscapes increasingly dominated by industrial forms” (Tsing et al. 2019:S186). Monofunctional landscapes have emerged as historical manifestations of exploitative practices, yet between two analytical poles, the “modular simplification” (ibid.)—the functional perfection of intended processes—and the “feral proliferation” (ibid.)—all that disturbs such perfection, entering unruliness into the simplified system. These two poles are substantially intertwined in shaping urban sandscapes: on the simplification side, mining reduces some landscapes to one function (i.e. sand extraction); on the feral side, mining engenders a wider array of social and political activities, conflicts, and affective relations, undermining homogeneous and monofunctional landscapes.

Secondly, I draw from Kothari's (2021) recent development of the term. They are critical to an understanding of landscapes in the phenomenological tradition as correlating with a subject-centred experience of the outside environment. They highlight sand's growing scarcity and highly lucrative nature (Torres et al. 2017) and argue that sand's embeddedness in ecological and political processes of landscape formation is crucial. Sandscapes are shaped by a global interest in sand yet connecting interests and activities and actors on a local scale; in addition, the affective dimension of sand extraction and its ecologically devastating effects are important. Sandscapes thus compile a set of contradictory affordances and projected interests. While sand exerts a central function for construction, it also raises desires in economic and political terms while in other cases threatening the physical environment of populations surrounded by sand extraction zones.

In the industrialised area of Baixada Fluminense, urban sandscapes emerge as geographies intricately interwoven across multiple politically and ecologically embedded sites. Kothari's conceptualisation suggests that sandscapes may not inherently imply an unlawful geography, despite sand's scarcity. However, due to the substantial demand, increased expenses for licensed extraction, and tax-related pressures, urban sandscapes foster a surge in feral activities. These multifaceted and often illicit activities create conflicts, challenging the presumed monofunctionality of sand mines. Consequently, the presented urban sandscape spans various sites within the political and economic value chain, fostering governance arrangements between formal state agents and militias. This multi-sited and multi-scalar perspective prompts a comprehensive examination of global discourses on sand scarcity, media representations of local governance, and associated illicit practices, along with an ethnographical focus on the affective dimensions.

In sum, I suggest using the term illicit urban ecologies to address the overlapping interests of criminal governance and UPE. Studying urban sandscapes allows further development of this term by both looking at the imbrications of formal state and criminal actors, and the political dimension and inequalities related to resource extraction and environmental processes. An Urban Illicit Ecology (UIE) thus explores the relationship between criminal governance and urban sandscapes. These situate claims to territorial influence and are also places from which we can better understand how claims to political authority and territorial control are ambushed, and militias and the state permeate one another.

Global Sandscapes: Sand Mafias Worldwide

This section looks at sand as a raw material within criminalised conflicts on a global scale. As a scarce and valuable raw material, sand provides a prolific ground for illicit market economies and governance arrangements. Sand is not only an object of illicit economies, but also forms urban sandscapes; that is, the political-material intersection of inhabitable land, construction, and governance arrangements, connecting sites of extraction and construction across rural and urban spaces.

As the demand for sand and civil construction grows, environmental conflicts aggravate (UNEP 2019). Even if sand is sufficiently available, its extraction, often from coastlines and riversides, is often restricted by national law and regulations for natural protection. Licensed or legal extraction is insufficient to satisfy the construction sector's hunger in many places of the world (Rege 2016). According to a study on the regulation of sand mining on a global scale, and illegal sand mining activity in particular, illegal sand mining is ranked third in revenue, with an estimated annual value of US$182–215 billion, following counterfeiting (about US$1 trillion) and drug trafficking (US$500 billion) and preceding human trafficking (US$150 billion) (GFI 2017). It has been argued that illegal sand mining has more environmentally devastating effects than legal mining (da Silva et al. 2020:58). Moreover, it is important to note that illegal mining fosters the political-economic positions of linked actors—in the case of Rio de Janeiro, constructors, mining companies, militias, and formal government representatives.

The intricate link between sand, vital for urbanisation and capitalism, is evident in its pervasive role in clandestine urban development, leading to violent clashes over this crucial material (Beiser 2018). Proposals to curb illicit sand extraction have emerged, yet concerns arise about impeding city expansion. This dilemma is tied to Harvey's (1985, 1990) insights, emphasising capital accumulation's centrality in urban settings and inter-urban competition, intensifying sand demand. Some argue illicit sand extraction results from high demand and strict regulations (Hackney et al. 2020; Leal Filho et al. 2021). Deeper exploration reveals an intrinsic link among capitalism, urbanisation, and crime. Advocates suggest that governments recalibrate policies to limit construction in rapidly urbanising nations (Lira 2018). Relying solely on environmental regulations, crucial for protecting landscapes, proves inadequate to curb illegal extraction. A critical conclusion arises: the capitalist logic in urbanisation, fixated on capital accumulation and generating (fictitious) value for the built environment (Harvey 2012), inevitably provokes crime. Urbanisation thrives on illicit practices, prompting questions about the current trajectory's sustainability and ethics.

Revenues from illegal, unlicensed sand extraction seemingly contradict the assumption about the problem-solving implications of sand mining regulation. In Brazil, it is the Agência Nacional de Mineração's (National Mining Agency's) responsibility to track and report the income generated by the mining industry in Brazil. In 2011, according to the CNM (National Confederation of Municipalities) the tax generated in Brazil (CFEM, Compensação Financeira pela Exploração Mineral) was R$1.34 billion, out of which R$20 million was taxes on sand mining (CNM 2012). If sand is taxed at the 1% tax rate and if in 2011 it generated R$20 million in tax revenues, one can infer that legal sand mining's total income that year was around 100 times the tax generated amount, or nearly R$2 billion. The illegal market of sand mining however has been estimated to generate R$13 billion in 2020 (Diário do Nordeste 2020), turning it into a more lucrative business than drug trafficking. The consumption of sand in the country only for civil construction was estimated at 214.2 tons in 2020, of which only 76.7 million tons were produced legally (ibid.). This imbalance between legally (scarce) and illegally extracted (abundant) sand offers criminal actors a very lucrative void to fill in the sand market.

In Brazil, two crimes related to sand extraction can be distinguished. Firstly, sand extraction can be an illegal usurpation of the Federal Republic's patrimony, according to Federal Law 8,166 of 8 February 1991. Secondly, it can mean committing an environmental crime, according to Article 55 of the Environmental Crimes Law (9,605 of 1998) (Ataíde 2017). Certainly, regulations aim to mitigate the severe social, environmental, and economic impacts of illegal sand mining, including environmental destruction, tax losses, and the promotion of illicit labour relations (Leal Filho et al. 2021:8). However, despite estimated figures, the revenue from illegal extraction suggests a deliberate (political) intention to maintain the scarcity of legal sand. In Brazil, illicit sand mining generates substantial revenues, estimated at US$1.6 billion annually (Ramadon 2016). Policing the mining activities of many enterprises and their correspondence with environmental laws proves challenging in the face of falsified licenses, manipulated geological evaluations of sand mines, and corrupt practices involving officials and engineers (Ramadon 2016:30–34). In essence, there appears to be robust licit–illicit arrangements in sand extraction, influencing the broader geology of urbanisation.

These arrangements, escalating social conflict, are fuelled by disputes over natural resource use and consumption. The combination of scarcity, limited licensed extraction, and resulting high revenues creates economic opportunities for crime, triggering subsequent social crises (Cabral de Oliveira et al. 2020). Against this backdrop, I delve into the impacts of illicit city building. While recent analyses of sand extraction politics, practices, and effects adopt a macro perspective with quantitative data (Bendixen et al. 2019; John 2021), the ethnography-based case study below examines the intricate connections between sand extraction, urbanisation, and their entanglement with criminal governance in Rio de Janeiro's peripheries. Seropédica, as the most heavily affected municipality by illegal sand mining in Brazil, will be explored in detail following a brief note on methods.

Notes on Research Methods

Fieldwork covered two episodes, the first from January to June 2019, the second from March to May 2022. For this paper, I interviewed 20 residents of the area of São Bento, Duque de Caxias, politicians, truck drivers, workers at sand mines, residents living close to the sand mines of Xerém, and academics working on the topic of militias. While I first became aware of the importance of sand and rubble in the militia-organised constructions along the river Iguacu in Duque de Caxias (Müller 2021a, 2023), the more focused objective to “follow the actors themselves” (Latour 2005:11) only occurred with a first visit to the former MST occupation Terra Prometida in May 2019 (see Müller 2021b). Talking to residents who have experienced menaces from gunmen, sent by the neighbouring sand mining companies, sand became a more important issue in my research on militias’ involvement in low-income housing. I traced this involvement of militias and local politicians further, knowing about then-Mayor Washington Reis supposedly being the owner of one of the sand pits in Xerém that was forcibly shut down at the end of 2019 by units of the Brazilian armed forces.

Upon recommendation of my interlocutor in Duque de Caxias, I searched for a local expert on militia activity in Seropédica, known to be the municipality where most sand mining activities in the state of Rio de Janeiro occur (see Figure 1). In 2022, I talked to two assistants of Professor Lucas (mayor of Seropédica) and visited some of the sand mines in the area where I held short conversations with guards, truck drivers, and other unspecified workers. While some of the mines displayed openly the licenses held at their entrances, others did not.

A disclosure on the use of the word “militia”: I refer to media reports that show the active involvement of formal state institutions in illicit city building and name the heads of militia groups in the city. However, I do not claim that all involved actors (sand mining companies, truck drivers, etc.) should be equally accounted for as “militias”. While I do sense a broad tendency in media and some academic literature to homogenise this actor, I hope to avoid this simplification, calling “militia” only those that are heading groups.

Urban Sandscapes: Zooming into Rio's Metropolitan Peripheries

This section will zoom into the area of Rio's metropolitan region and trace the extraction of sand from Seropédica (a municipality in the north of the state of Rio de Janeiro), including gravel and rubble, towards the urbanising areas further southeast and adjacent to Guanabara Bay. Seropédica, in addition to the municipality's proximity to the civil-construction-intensive city of Rio de Janeiro, also offers geological advantages for the extraction of sand, such as a phreatic surface that offers easy access to open sand pits by means of low-tech drainage systems. Before presenting ethnographic insights to approximate sandscapes, I wish to outline the term urban sandscape.

Seropédica has an abundance of sand to offer that, when processed from raw material into resource, serves militias in their expansion of territorial power and gain of economic benefit. Gaining importance as an industrial nucleus, sand mining is now one of the most important economic activities in the formerly agriculturally dominated area of Seropédica. An area of about 600 hectares in this municipality has become one of the two most important sand extraction areas of Brazil since the 1950s (Berbert 2003; Tubbs et al. 2011), motivating studies to mitigate the devastating environmental impacts of unsustainable mining activities (Schueler et al. 2019). The State Institute for the Environment (INEA, Instituto Estadual do Ambiente) is responsible for issuing and revoking licenses for mining activities. Put in practice together with the National Department of Mineral Production (DNPM, Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral), INEA monitors all related activities and receives requests for regularisation throughout the entire Brazilian territory (INEA n.d.).

Most of the sand pits had been exploited in the decade before 2014, with only a few having been opened in the seven-year period afterwards. However, firstly, Figures 2 and 3 show that the sand pits have slowly refilled with water, which mainly flows from the nearby river Guandu, thus reducing access to fresh water for residents in the area. Secondly, these images are also proof of a lack of accountability and responsibility of the sand mining enterprises which, by law, are obliged to re-naturalise and recuperate exploited sand mines, according to Article 225, §2° of the Federal Constitution. Besides this, even though some enterprises operate with licenses, they do not hold licenses to extract sand on the scale and in the amounts they do (Ramadon 2021). These processes are reminiscent of the abovementioned case studied by Jamieson (2021) on the transformation of fluid and firm (land) bodies.

The municipality concentrates 85% of all sand extraction in the state of Rio de Janeiro while only holding 21% of all licenses for extraction. A detailed study of sand mining operations in Seropédica, Rio de Janeiro, demonstrates that, at the time, approximately 100 firms were involved in this business and held licenses for such (ACCAMTAS 2020). According to the Annual Certification Report of the DNPM, the 38 largest firms among these extracted 723,000 m3 of sand in 2014, which amounts to approximately US$4.2 million in revenue. Building on this insight, ACCAMTAS adds combined data from the DNPM and satellite images to show that extraction exceeds by far the licensed operations, also demonstrating that not only the extraction, but also the ignored obligation for re-naturalisation of formerly exploited sand pits constitute environmental crimes (ACCAMTAS 2020).

During the 2016 Olympics-related urban development, illegal mining surged, particularly in areas controlled by militias (Ramadon 2016). Sand mining, a theoretically open economic activity, is accessible to anyone with the landowner's agreement and proper licenses from INEA and the municipality. However, environmental risks persist, especially in water-rich regions like Seropédica, where extracting sand leads to water-filled pits, severely restricting residents’ water access. This issue intensifies when clandestine enterprises and organised crime enter the sand mining scene, as highlighted by Alexandre Herdy from DRACO (Repression of Organized Criminal Actions and Special Inquiries, a police special force against organised crime), directly linked to Olympic Games construction (O Globo 2016).

Media frequently highlight the intertwining of militias with local politics, particularly after crackdowns on the sand and construction industry. In a coordinated effort, the civil, military, and federal police aimed to curb militias’ illicit sand extraction in Rio, implicated in the 2019 collapse of two Muzema buildings that claimed 24 lives. Operating in ten locations in Seropédica and Itaguaí, the operation utilised satellite monitoring. The criminal investigation named Tubarão and Tandera as leaders in sand extraction (Monteiro and Nascimento 2023). Militias coerce businesses into monthly payments exceeding R$500,000, with the report linking illicit sand extraction in Seropédica to the Muzema collapse, revealing broader criminal dynamics (Jovem Pan 2023). Danilo Dias Lima's ascent in Itaguaí, aligned with Ecko, underscores the persistent criminal influence and violence of these paramilitary entities, as detailed in a GAECO-led investigation (Santos and Brasil 2023).

Sources within Seropédica's municipal administration, during Mayor Lucas Dutra Dos Santos's tenure (PSC, Social Christian Party), confirmed media reports on the mayor's connections with local militias. These militias have gained wealth through overseeing sand extraction, now exerting significant influence over the municipality in terms of population, business sectors, and politics. Conversations with a source (V) revealed that Mayor Dutra Dos Santos had secured financial and electoral support from local mining companies for the 2021–22 elections but was now facing verbal threats from militia leaders (Interview, V, Seropédica, May 2022). With municipal bodies controlling extraction licenses and 70% of mining taxation benefiting the treasury, influencing the mayor's office proves advantageous. Despite no federal limit on the absolute number of licenses, militias concentrate in one municipality due to the cost-effectiveness of unlicensed extraction and the ease of obtaining licenses when in control. This underscores how the concentration of sand mining in a single municipality is directly linked to illicit practices.

Moving closer to the city of Rio de Janeiro, into an area in which unlicensed mining activity has received less media attention, in Xerém the connection between environmental crime and construction can be demonstrated based on the often-illegal mining, delivery, and commercialisation of sand for construction and soil preparation services. Similar to the area of Seropédica, in Xerém, north of Rio de Janeiro, militias are investing in sand mining and have confronted several military police raids over the last few years (Diário do Porto 2019; EcoDebate 2020) (Figure 4). The former mayor of Duque de Caxias has been sentenced to seven years in prison for environmental crimes, particularly for irregular subdivisions for construction purposes and real-estate speculation, in 2016. In 2020, the mayor also supported the decision of the Brazilian land reform institute (INCRA) that allowed the construction of a huge supply and logistical hub in a natural reserve (Carta Capital 2021).

This quotation refers to a two-fold threat: adding to the actor's armed presence, the resident speaks about their fear of landslides in their land plot if mining continues. Alarmed by new cracks emerging in the outer structure of the primary school at the shores of a sand pit, parents and teachers decided to temporality close the building. I was also told that a child went missing after playing in the closed lagoons and sand pits. This once more made the respondent point both to the dangerous instability of the sand pits and the dramatic lack of responsibility towards mining regulations, in proximity to urbanised areas and without proper safety measures (Figure 5).They arrive at night at my door; in the back, their men fire weapons into the air, just to intimidate us, and they leave one message: “Do not get in my way.” This has happened to me and my neighbours, many times in the past, and now even more, as the sand pit moves closer and closer to our land. (Interview with resident of Terra Prometida, June 2019)

The urban sandscapes of Rio's metropolitan area extend into Baixada Fluminense, a water-rich region bounded by Guanabara Bay to the east. Since the 1960s, communities in this area have relied on collective self-organisation to prepare the land for single-storey house construction. Sand, essential for drainage in proximity to bay and river, is easily transported and mixed with gravel for a stable foundation. Despite its suitability for rapid ground preparation, improperly cemented sandy grounds forewarn of instability. Lack of heavy machinery in poorer communities necessitates dependence on individual entrepreneurs, contributing to political negotiations between state and local authorities and construction entrepreneurs. Community leaders serve as intermediaries, endorsing candidates who tolerate land appropriation (Koster and Eiró 2022). In this situation, yet also when land invasion had been collectively organised by nation-wide social movements, settlements have often remained exposed to eviction (Albert 2021).

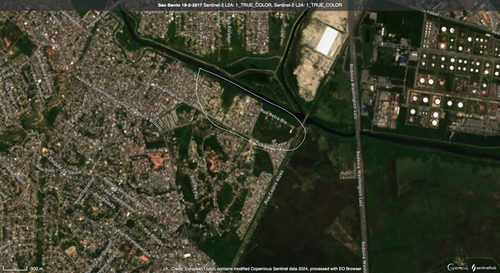

During my fieldwork stay in Duque de Caxias, from January to June 2019, I followed a pressure group which has been fighting against what they perceived as unjust urbanisation processes. In particular, the residents represent(ed) about 400 settlers along the Iguaçu river who, although they were initially promised an apartment in the newly constructed social housing condominium in São Bento, were passed over, as families from another riverside were resettled instead (Müller 2021a). Due to their good relationship with state attorney “Dr. Julio”—as they referred to him—who accompanied their case towards the local state authorities, the residents eyed a chance not only to receive a just treatment but also to make the illicit processes publicly visible. To support this process, Dr. Julio proposed the collection of evidence (protocols and photos) of the ongoing illegal construction activity in the areas that had already been declared risk areas. These areas are uninhabitable due to proximity to the flood-prone Iguaçu river, yet they are continuously subdivided, cleaned, and prepared for construction by the local militia (see Figures 6 and 7 for a comparison over time, where the circles highlight the risk areas in which construction went on) (MPF 2019).

As members of the pressure group made it clear, their struggle has been a story of unfulfilled promises. As far as they have reported, local militia managed to resettle their own clientele to the social housing compound and thereby to cater to the interest of then Secretary of Urban Planning (in 2019). The land grabber, grileiro, organises the preparation of land plots for construction, as well as construction itself, and sells these plots, while s/he also acts as the representative in resettlement negotiations with the Secretary. This process is described by one of the residents of the nearby squat, Ocupação Solano: “The area's biggest land grabber carries sand and drains the riverbank, and now his people have been resettled to the unidades, the social housing development [of São Bento]” (Interview, 15 May 2019). Militias have also been extracting clay directly from an open pit in São Bento in order to provide space for the construction of new houses and generate revenue and to retrieve material for construction and soil preparation throughout the community. Opposition to such land grabbing (grilagem) has motivated residents’ political and juridical struggles for years (Focus group with activists, community of São Bento, 22 April 2019).

From the banks of the Sarapuí river, the residents were rehoused to the social housing developments of São Bento. To avoid flooding of their property, homebuilders pile up sand and rubble purchased from local construction firms, linked to the militia (see Figures 8, 9, and 10). The people inhabiting the riverbanks of Sarapuí, like those living close to Iguaçu, lived in declared risk areas, and their resettlement was more of interest to the Secretary whose infrastructural project foresaw the connection of Gramacho, Duque de Caxias, to the main highway, Rodovia Washington Luiz. The houses along Sarapuí had been demolished before 2021, and the soil prepared for the construction of the connecting street, leaving a sandy pitch along the river where once a community had formerly settled (see Figure 11).

This urban sandscape thus rests on the illicit exploitation of sand as well as on a strong win–win relationship between militia and local politicians. In an interview, Marcelo Freixo (formerly PSOL, Socialism and Liberty Party, now PT, Workers’ Party) characterised such illicit governance: “These groups transform territorial control into electoral control. In other words, they trade the votes of those whom they have in a stranglehold. And this is of interest to many politicians” (Interview by email, 16 June 2019). Freixo headed a Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) on militias and their ties to politicians and the formal polity in Rio de Janeiro in 2008. The CPI identified 225 persons, among them firefighters, police officers, military personnel, and prison guards as having ties with organised crime in Rio de Janeiro. Fostering such arrangements, as then Secretary for Infrastructure of Duque de Caxias explained in an interview: “If you want resettlement to occur smoothly and without resistance, you need the mobilising influence of the local gang leaders” (Interview, 3 June 2019).

In a meeting with state attorney Dr. Julio and representatives of INEA, the municipality's government as well as the local pressure group, the local government's representatives made it clear that they knew about the ongoing constructions and the illegal plotting of land. When asked why they did not bother to stop the access of trucks that carry sand and gravel into the communities dwelling on the riverbanks, the representative admitted that they had no fiscal capacity to oversee these illegal actions, since the military police had refused to support and secure their interventions (Author's notes and recordings, São João de Meriti, 26 June). However, as the pressure group pointed out, the construction of a new polder to capture and store rainwaters, financed by the municipality, had only fuelled the local militia to continue construction of houses in the risk area along river Iguaçu.

Many São Bento residents inhabit precarious grounds, providing a viable avenue for militia-led construction to expand political influence and boost profits. With promised resettlement to state-funded housing delayed, residents often resort to purchasing flood-prone plots or hoping to establish on-site presence over years for a legitimate claim to subsidised housing. Militias adapt their activities to the region's geological conditions, urbanising declared flood-risk zones and selling them as the sole alternatives, bolstering their power and supporting illiberal governance driving urbanisation.

Urban sandscapes present a productive geographical angle to look at the imbrications of illicit activities, construction, and formal politics. This way, urban sandscapes allow us to further leave behind clearcut binaries between formal/informal, illegal/illegal spheres of urban governance (Müller 2019; Roy 2009). In the case of sandscapes, however, such blurring cannot mean taking an uncritical perspective on unlawful sand mining. While there is a “continuum of (il)legality” (Magliocca et al. 2021:57) in sand mining activities, the state and (legal) real-estate enterprises are driven by their democratically gained mandate, or chances for profit. Reports on the illicit dimension of sand mining, blaming weak governments for the criminal extraction to be condemned morally, may support a legalist view that covers up the capitalist drive to urban expansion as being at the heart of the problem (Salle 2022). However, the real estate industry, which is well known for corruption and unofficial transactions (Chiodelli and Gentili 2021; Moreno Zacarés 2020), is a good illustration of formal and legal entities being involved in illegal activities.

Conclusion: Towards an Urban Illicit Ecology (UIE)

This paper delved into the intricate nexus between terrain, sand extraction, and the socio-political and economic roles of militias in governing Rio de Janeiro's northern periphery. I've unravelled how illicit practices destabilise human–urban environment relations, exacerbating the marginalisation of low-income communities in contemporary cities. Militias actively mould the terrain for political and economic gains, weaving interconnected value chains that span sand mines, urban services, and construction, reaching into the political echelons of the Brazilian state. In contrast to Jorge Amado's portrayal, today's captains of the sands are deeply enmeshed in formal governance structures, particularly in peripheral urbanisation, leveraging this integration to amass political influence at the expense of socio-natural environments.

Grounding my analysis of local governance arrangements on the extraction, delivery, and foundational function of sand, I have offered a way to rethink human–environment relationships in their illicit guise. Geological conditions (the phreatic surface, swampy stretches, and sandy ground) permeate Baixada's illicit governance arrangements. Not only does the lack of formal housing alternatives call other illicit actors onto the stage of housing markets, creating business opportunities for them, but it is also the pragmatic alliance with municipal secretaries, as well as the liaisons with local politicians and their investment in local development, that form an urban sandscape. Residents’ responses involve active engagement in safeguarding the built environment, which highlights the affective relationships of cities’ inhabitants to the ground on which they dwell. Sand extraction disrupts residents’ connections to their homes, exposing them to the dangers of floods, landslides, and forced displacement. This prompts residents to continually forge new social alliances to ensure the security of their homes.

Studying urban sandscapes thus allows us to add to geographers’ growing interest in the political materiality of terrain and territoriality. In Elden's (2021) procedural and volumetric understanding of terrain, sand, gravel, and phreatic surfaces (swamps and riverbanks) constitute the politico-material condition of sovereignty. In moulding such firm-to-fluid volume, the set of actors described here also articulate claims to urban sovereignty. Contributing to socio-environmental devastation in Rio de Janeiro's territory, the urban sandscape continuously informalises development, undermining state attempts to rehouse communities and forcing residents into the illicit housing market. Sand is different from other business areas in which militias are involved: it is crucial for urban construction; a way to control physically the expansion of areas of influence by construction and a way to bind clients into loyal relationships; sand's function in producing inhabitable terrain, and in founding political support and clientele, underlines its importance within contested claims for urban sovereignty.

The analysis of local sandscapes should be situated in larger contextual environments of capitalist urbanisation. Due to the growing demand for sand for urbanisation and other forms of capitalist consumption, such as glass, electronic equipment, plastics, and water filtration, the “looming tragedy of the sand common” (Torres et al. 2017) further engenders illicit capitalist urbanisation in particular. The fact that licensed sand extraction is more costly than unlicensed, and the observation that obtaining or avoiding licenses orchestrates mutually beneficial militia–politician–extractive industries liaisons, undermines efforts of ecological protection. While, thus, scarcity might be looked at as a lucrative condition for the sand mining business, and at the same time, is the result of attempts to reduce sand extraction by limiting the issuance of licenses, the high demand for sand does drive illicit practices.

Examining the legal and illegal underpinnings of urban geologies on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, I aim to contribute to the “provincialisation” (Lawhon et al. 2014) of Urban Political Ecology (UPE). The intersecting analysis of criminal governance and UPE challenges the assumption that lawful urbanisation is the global norm. Cities are constructed on sandy terrains that cannot sustain legal and sustainable levels of raw material extraction. Thus, proposing a focus on Urban Illicit Ecology (UIE), I emphasise the link between global capitalism and ecological crises within historically unjust governance arrangements. The case of sand underscores the disparity between the demand for sand in legal urbanisation and its sustainable extraction. This leads to devastated landscapes, disproportionately affecting marginalised populations. While this paper empirically supports this claim, further research should confirm the intrinsic connection between (capitalist) urbanisation and its dependence on illicit governance in postcolonial settings.

Acknowledgements

I extend my sincere appreciation to all the interviewees who generously contributed their time, trust, and perspectives to enrich this research. Special thanks to Diane Davis for her valuable insights on earlier drafts of this paper, to Manoel Pereira Neto for the research assistance, and to the members of the research group “Casa” at the Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, led by Mariana Cavalcanti, for their constructive critiques. Gratitude is also owed to the anonymous reviewers whose meticulous feedback greatly aided in refining and streamlining this paper. Lastly, I thank the editorial team at Antipode for their patience and support throughout the publication process.