E kaua e hoki i te waewae tūtuki, ā, apā anō hei te ūpoko pakaru – a systematic review of neurosurgical disease and care for Māori in New Zealand

Abstract

Background

The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) Te Rautaki Māori cites the need for more research dedicated to health equity in surgery for Māori. However, the gaps in research for Māori in surgery have not yet been highlighted. This review is the first in a series of reviews named Te Ara Pokanga that seeks to identify these gaps over all nine surgical specialties. The aim of this study was to assess neurosurgical disease incidence and perioperative outcomes for Māori at any point from referral through to the postoperative period.

Methods

A systematic review of Māori neurosurgical disease and care for Māori in NZ was performed. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement assisted study selection and reporting. Kaupapa Māori (Māori-centred) research methodology and the Māori Framework were utilized to evaluate Māori research responsiveness.

Results

Nine studies were included in this review. All studies were retrospective cohort studies and only two studies had at least one Māori clinical or academic expert named on their research team. Therefore, only one study was deemed responsive to Māori. Studies assessing long-term outcomes from the management of neurosurgical disease for Māori and patient and whānau experiences of neurosurgical care are lacking.

Conclusion

This study indicates the limited scope of research conducted for Māori in neurosurgery. The broader clinical implications of this review highlight the need for good quality research to investigate access to and long-term outcomes from the management of neurosurgical disease for Māori.

Introduction

Neurosurgery is one of nine surgical specialties for which the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) is responsible for training neurosurgeons in Aotearoa, New Zealand (NZ). Neurosurgeons diagnose and treat patients with disorders of the central, peripheral and autonomic nervous system including their supportive structures and blood supply.1 Few studies investigating neurosurgical disease on a population-level in NZ exist.

A systematic review summarizing disparities in surgical care included studies that reported surgical outcomes for Māori at any point along the surgical care pipeline yielded no studies assessing neurosurgical disease incidence and outcomes specifically for Māori.2 The recent RACS Māori health action plan identified six priority areas including research and development using kaupapa Māori methodology.3 However, a strategy outlining where the gaps are in surgical research for Māori, and whether current research is responsive to Māori, is lacking.

To address these gaps, we conducted a scoping review of all studies reporting access to, experiences of, and outcomes for Māori over all nine surgical specialties.4 This review yielded over 200 studies and upon assessing their responsiveness to Māori, we determined that each surgical specialty required a focussed review. This study aimed to summarize the literature related to neurosurgical disease incidence and perioperative outcomes for Māori at any point from referral through to outcomes following neurosurgical care. Second, we sought to assess each study as to their responsiveness to Māori in order to highlight areas of improvement needed going forward.5

Methods

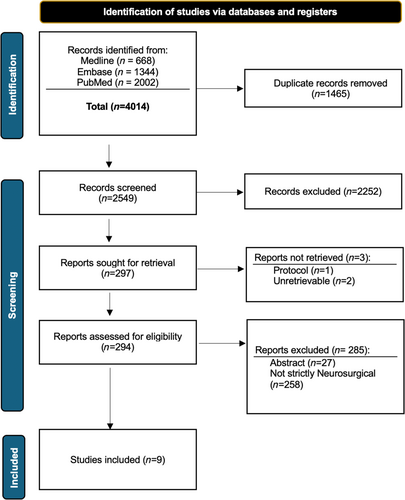

This systematic review is an extension of a larger scoping review and provides an in-depth analysis of studies reporting neurosurgical disease incidence and outcomes, and their responsiveness to Māori.4 The reporting of this review is in accordance with the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement where possible.6

Methodology

This study was informed by Kaupapa Māori research (KMR) methodology to ensure responsiveness to Māori whilst seeking to monitor the neurosurgical disease and care pipeline for Māori.7 Kaupapa Māori Research methodology can be used in quantitative studies that seek to advocate for the eradication of Māori health inequities.8 Accordingly, this study was led, governed and conducted by Māori clinical academics (J-LR, MH and JT) and adopted a tuakana-teina approach through research supervision and mentorship. This work has been disseminated in the Indigenous Health section of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons Annual Scientific Congress (2024) held in Christchurch, NZ.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they reported ethnic differences in neurosurgical disease incidence and perioperative outcomes in NZ with any comparison made between Māori and non-Māori children and adults. International studies were included if the results were reported separately for NZ. Editorials, perspective pieces, non-consecutive studies and articles for which full texts are not available (i.e., conference abstracts) were excluded. Studies reporting traumatic brain injury hospitalisations without any specific data on care provided by neurosurgeons were excluded however, these studies will be included in a separate review of studies describing the incidence and surgical trauma management for Māori compared with non-Māori in NZ. No language or time restrictions were applied.

Search strategy and study selection

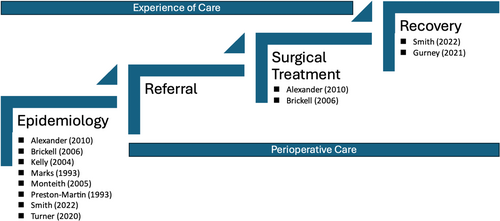

Electronic searches of MEDLINE, Embase, PubMed and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Plus databases were performed (Appendix A). Two reviewers (J-LR and JT) independently performed the searches and identified eligible texts in an iterative manner followed by verification from a third reviewer as required (MH). The last search was performed on March 12, 2024. Relevant titles and abstracts were retrieved and managed in Endnote V.20 (Clarivate Analytics, USA) reference management software. All data were entered into an electronic spreadsheet and each included study was charted independently by two reviewers (MM and J-LR). The table was designed in line with the following data variables anticipated for extraction: study type, year, study aim and outcomes. The study was placed along a simplified surgical care pipeline diagram to visualize the gaps in neurosurgical research for Māori.

Assessment of responsiveness to Māori

Each included study was assessed as to its responsiveness to Māori using a simplified reporting framework consisting of five domains: Māori leadership, advocacy for health equity, opposes deficit analysis, rejects racism and indigenous data sovereignty.5, 9 Our research team includes a range of Māori health experts with expertise in surgery, primary health care and Māori health who could provide adequate assessment of the key domains of Māori research responsiveness.

Risk of bias

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) quality assessment scale for cohort studies was used to measure the risk of bias. Assessment of selected studies focused on three domains: selection, comparability, and exposure.10

Results

Nine articles were included in this review with Figure 1 outlining the flow of studies screened and selected in an iterative manner. All studies employed a retrospective cohort design with two studies utilizing national NZ datasets (Table 1). Figure 2 outlines where on the surgical care continuum these studies are situated.

| Study (Year) | Aim | Type | Population | Māori (n/total) | Conclusive findings | Newcastle Ottawa Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander (2010)11 | Assess management of high-grade glioma in Māori versus non-Māori | Retrospective cohort study | Wellington Hospital (1993–2003) | 19/301 | Age-sex standardized HGG incidence was 4.2 (95% CI 2.6–6.9) per 100 000 person years compared to non-Māori of 4.1 (95% CI 3.6–4.6). Māori were more likely to have complete tumour resection (OR 3.59 (95% CI 1.01–12.76)) but waited longer 1.32 from surgery to starting RT (95% CI 0.98–1.79 age-adjusted). Median survival was 29 weeks with poorer survival in Māori (hazard ratio 1.55 [95% CI 0.95–2.55]). | ***||*** Good |

| Brickell (2006)18 | 1961–2003 – patients diagnosed with syringomyelia | Retrospective cohort study | Auckland, Northland Hospitals +3 private surgeons databases. | 28/137 | The prevalence of syringomyelia in 2003 was 8.2/100000 people: 5.4/100000 in Caucasians or others, 15.4/ 100 000 in Māori and 18.4/100000 in Pacific people (x2 = 37.0, P 0.0001). | ***|-|* Poor |

| Gurney (2021)20 | To assess postoperative 30 and 90-day mortality between Māori and non-Māori in NZ. | Retrospective Cohort Study | National (NMDS) (2005–2017) |

312/2268 acute 46/887 elective |

Māori are 1.06 times (95% CI 0.92–1.22) as likely to experience acute 30 day post-surgical mortality, however this value did not reach statistical significance. | ***|**|*** Good |

| Kelly (2004)17 | Assess traumatic SDH in infants <2 years with particular regard to features which might help to differentiate accidental from NAI. | Retrospective cohort study | Auckland/Starship Hospitals (1988–1998) | 30/64 | More Māori in the NAI group (P = 0.008). 5/11 cases had fractures and 8/11 had RH (in 6 cases, bilateral). 3/ 11 cases died and 3/30 cases of NAI with a history also died. | ***|- |** Poor |

| Marks (1993)15 | Compare clinical, epidemiological and radiological features of aneurysmal SAH between European and Māori | Retrospective cohort study | Auckland 1985 and 1990 | 71/280 | Incidence 14.3/100000 for Europeans and 25.7/100000 for Māori. Māori had higher than expected incidence of MCA aneurysm and a lower than expected incidence of vertebra-basilar lesions. Total of 49% of Europeans who had multiple aneurysms had evidence of pre-existing HTN compared with 26% of Māori. No significant difference in grade at presentation. | ***|-|*** Poor |

| Monteith (2005)12 | Assess prevalence, management and outcomes of paediatric CNS tumours | Retrospective cohort study | Auckland/Starship Hospital (1995–2004) | 41/166 | Medulloblastoma (15/36) incidence of 1.37/100000/year for Māori compared to NZE (0.59/100000/year, P < 0.01). Māori had a higher incidence of brain tumours than non-Māori. ‘Māori and Pacific Islanders traditionally have fared poorly in NZ health statistics, and so expected these groups to have a longer delay before seeking medical attention’. | ***|-|*** Poor |

| Preston-Martin (1993) | Descriptive epidemiology of primary brain cancer, cranial nerves, and meninges in NZ. | Retrospective cohort study | National – NZCR (1948–1998) | 255/5601 | The proportion of medulloblastomas is about four times higher than the corresponding proportion among non-Māori (15.8 cf. 4.0%). | ***|-|** Poor |

| Smith (2022)16 | Assess aneurysmal SAH in Māori and European New Zealanders |

Retrospective cohort study | Wellington Hospital (2010–2017) | 82/358 | Higher incidence in Māori (5.07 versus3.67 /100000) but no statistically significant disease characteristics like rates of single or multiple aneurysms. Higher incidence for vasospasm (controlling for age, sex, HT, smoking, aneurysm local and MFS grade). Māori less likely to experience excellent neuro recovery and more likely to survive with greater levels of disability. | ***|**|*** Good |

| Turner (2020)14 | Examine relative rates of meningioma among Māori and Pacific Island patients compared to other ethnic groups | Retrospective cohort study | Auckland Hospital (2002–2011) | 88/493 | Māori had a meningioma incidence 2.74 times that of Europeans (95% C.I. 2.01–3.73, P < 0.001). Māori were younger at time of onset and tumour recurrence. | ***|**|*** Good |

Epidemiology of neurosurgical disease

Four studies investigated the prevalence of primary central nervous system (CNS) tumours between Māori and non-Māori in their series.11-14 Māori had a meningioma incidence 2.74 times that of Europeans,14 and a medulloblastoma incidence 3.95 times higher than non-Māori.13 A higher proportion of brain cancers were not histologically confirmed for Māori which was attributed to a higher proportion of Māori living in rural areas with reduced access to specialty care.13 However, higher rates of resectable primary CNS tumours for Māori were observed.11-13 Additionally, Monteith et al., reported that whilst Māori children had a medulloblastoma rate 1.94 times that of non-Māori, this was statistically insignificant.12

Three studies investigated the incidence of intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) with two studies assessing aneurysmal SAH,15, 16 and one study assessing traumatic SDH in infants.17 In Smith et al., Māori adults were 1.38 times (95% CI 1.08–1.77, P = 0.01) more likely than Europeans to experience an aneurysmal SAH.16 This study also conveyed that Māori tended to have higher rates of anterior circulation aneurysms. Congruent with the studies assessing primary CNS tumour prevalence, Māori also tended to present at a younger age.16 Marks et al., also assessed aneurysmal SAH and reported that Māori were 1.8 times more likely than Europeans to experience an aneurysm.15 The mean age of rupture of singular aneurysms was 10 years younger in Māori, and Māori had a higher incidence of middle cerebral arterial aneurysms.15 Kelly et al. showed that Māori comprised 47% of infants ≤2 years of age presenting with traumatic subdural haemorrhage (SDH) and that Māori were overrepresented in the non-accidental injury (NAI) group (P = 0.008).17 One study assessed the prevalence of syringomyelia, a benign condition whereby a fluid-filled cyst (syrinx) may develop in the spinal canal, highlighting that Māori were 2.85 times more likely to be diagnosed with syringomyelia than Caucasians (P < 0.0001).18

Access to services

Attendance and access to private and public neurosurgical services; including outpatient clinics, and acute and elective admissions to hospital were not meaningfully assessed among the included studies. Monteith et al. reported no statistical difference in duration of symptoms and signs related to paediatric CNS tumours until presentation to neurosurgical services for Māori compared with Europeans.12 In regards to adjuvant radiotherapy for high-grade glioma (HGG), Alexander et al. reported that Māori waited 1.32 times longer than non-Māori (age-adjusted) to commence radiotherapy, although this was not statistically significant.11

Perioperative outcomes

Three studies reported perioperative outcomes for Māori.11, 16, 19 In Alexander et al., Māori were 3.59 times more likely to undergo a complete resection of HGG compared to non-Māori.11 In Smith et al., Māori appeared to have a higher incidence of vasospasm, after controlling for age, sex, hypertension, and smoking history postoperatively compared to European New Zealanders.16 In this series, Māori were also less likely to experience excellent neurological recovery and were more likely to survive with greater levels of disability. Gurney et al. performed a large epidemiological study measuring post-operative mortality across all surgical specialties in NZ and found no significant difference in 30-day mortality following both acute and elective neurosurgical operations for Māori compare with non-Māori (HR1.06, 95% CI 0.92–1.22).20

Responsiveness to Māori

Table 2 summarizes the assessments for Māori research responsiveness of each study. Two studies exemplified Māori collaboration through Māori leadership within the research team.16, 20 Five studies acknowledged Māori as tangata whenua however, no studies reported hapū or iwi engagement.11, 13, 16, 18 Three studies did not provide any surrounding literature regarding Māori health inequities.12, 14, 18 Overall, three studies fulfilled at least three of the five criteria for Māori responsiveness.

| Study | Māori leadership + engagement | Advocacy for health equity | Opposes deficit analysis | Rejects racism | Indigenous data sovereignty | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander (2010) | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | First study to discuss racism and colonization. |

| Brickell (2006) | X | X | X | X | X | No supporting literature around health inequities |

| Gurney (2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | Fulfilled most criteria led by Māori researchers |

| Kelly (2004) | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | No supporting literature around health inequities |

| Marks (1993) | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | Does not position Māori as ‘the problem’ |

| Monteith (2006) | X | X | X | X | X | Sought both national and regional Māori ethical approvals |

| Preston-Martin (1993) | X | X | X | X | X | No supporting literature around health inequities |

| Smith (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | Up to date supporting literature surrounding health inequities. Critiques structural processes, systems, organizations and policies. |

| Turner (2020) | X | X | X | X | X | Up to date supporting literature surrounding health inequities |

Two studies acknowledged colonization as the fundamental cause for Māori health inequities and both affirmed the Treaty of Waitangi as the founding constitution of NZ and that the Crown must protect, uplift and advance Māori health.11, 16 In contrast, Turner et al. inferred that higher rates of meningioma in Māori could be due to a genetic predisposition.14 This has potential harmful ramifications and can promote misinformation without acknowledgement of the contemporary colonial contexts of Indigenous peoples and the impact on inequitable health outcomes. In Preston-Martin et al., where Māori had a higher proportion of brain tumours without histological confirmation, this was attributed to rural residency and differing cultural practices.13 They reported that Māori were less likely to consent to a cranial autopsy due to Māori cultural practices with an anecdotal report of whānau of deceased Māori being less likely to consent for an autopsy.13 No attempt to understand this from a Māori worldview was made which would not be possible anyway due to the absence of Māori leadership within the research team.21

Two studies cited racism as a determinant of health in NZ with one study critiquing how racism operates at multiple levels, particularly within the healthcare system.16, 20 Five of the included studies include data that predates 1996 where the definition of Māori ethnicity changed.11, 13, 15, 17, 18 Until September 1995, an individual was required to have equal to or greater than 50% Māori ancestry for their ethnicity to be recorded as Māori on their death certificate as opposed to the current definition of ethnicity being self-identified.22 Preston-Martin et al. included data from as early as 1948 and acknowledged that ethnicity was not recorded in health data.13 This has vast implications on the validity of the data being used through the significant undercounting of Māori through ideologies of essentialism and blood quantum.23, 24 Alexander et al. acknowledged this by attributing the higher incidence of HGG observed in Māori to the changing definition of ethnicity.11 Lastly, no study explicitly acknowledged the mainstream ‘control’ of health data for Māori. Smith et al. was the only study to state that they sought the minimum standard Māori ethical approval at both a national and regional level.16

Study quality

Only three studies were considered ‘good quality’ largely because they performed superior statistical analyses including regression analyses adjusting for age and sex at minimum.11, 14, 16 The remaining studies were of poor quality (Table 1).

Discussion

This study indicates the limited scope of research that has been explored for Māori in the neurosurgical space with only nine studies included. The broader clinical implications of this review highlight the need for good quality research to investigate access to, and long-term outcomes from, the management of neurosurgical disease for Māori. With only one study meeting the threshold for being responsive to Māori, this review also affirms that any further research must be conducted in a culturally safe and responsive manner to adequately record neurosurgical disease, surgical care and outcomes for Māori.

The WAI2575 inquiry was an independent Health and Disability System Review which found that the NZ health system has failed to recognize and properly provide Māori self-determination and autonomy over our health.25 This inquiry led to the recommendation that the healthcare system should adopt the following Treaty principles: tino rangatiratanga, equity, active protection, options, and partnership.25 Indigenous data sovereignty is a mechanism by which all principles are upheld seeking to safeguard Māori data. Kukutai et al. remark that by ‘honouring tino rangatiratanga and partnership of data, the data obtained must reflect the interests, values and priorities of Indigenous peoples’.26 This means that Māori tribal communities have absolute mana (authority) over the content of their data and control access and censorship of data parallel to all government systems.27 This review shows that surgical research utilizing Kaupapa Māori epistemologies and methodologies are yet to be performed and that the principles of data sovereignty for Māori are not yet being applied. Whilst many overarching governance changes are required, researchers may refer to resources such as those of Te Mana Raraunga which describe how good data stewardship for Māori can be practiced.28

Although limited in detail, one study measured post-operative mortality for Māori following acute and elective neurosurgical procedures.20 Neurosurgery was the only surgical specialty for which ethnic disparities in post-operative mortality were not observed for Māori. The authors purported this may be due to higher morbidity and mortality associated with neurosurgical procedures and the small number of neurosurgical providers in NZ.20 Several studies have shown that Māori experience higher rates of traumatic brain injury (TBI) with most datasets reporting mild TBI.29-31 Patients presenting with TBI are not routinely managed by neurosurgeons and as a result, these studies were not included in this specific review but will be included in a soon to be published review describing trauma incidence, management and outcomes for Māori in NZ.7

There are several limitations to this review. Most studies are outdated, and this factor alone likely explains the lack of Māori responsiveness given the significant growth in Māori scholarship that exists in contemporary NZ. Whilst we acknowledge that neurosurgical disease is often rare and that the volume of neurosurgical procedures taking place in NZ leads to smaller case-series that are underpowered, the quality of studies in this review restricts its strength in outlining neurosurgical disease and care for Māori. For instance, Smith et al. estimated that they would need more than 1000 total participants, including over 200 Māori individuals, to effectively examine differences in aneurysmal SAH.16

The title of the article, ‘E kaua e hoki i te waewae tūtuki, ā, apā anō hei te ūpoko pakaru’ is a proverbial saying alluding to not turning back due to minor obstacles in your path, but perservering through to your desired destination.32 This study provides a reference point for understanding neurosurgical disease and care for Māori in NZ. Despite a paucity of literature, with mostly small datasets, Māori appear to have an elevated incidence of primary CNS tumours, a higher likelihood of presenting with aneurysmal SAH, and present at a younger age compared to NZ Europeans. In addition, most studies were suboptimally responsive to Māori, based on contemporary Māori scholarship, being notably deficient in meaningful collaboration with Māori researchers or community leaders. Further research for Māori is required, however, it is imperative that these future research efforts are undertaken in a culturally safe and responsive manner, with Māori clinical, academic and community leadership.

Author contributions

Maiea Mauriohooho: Formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft. Jason Tuhoe: Data preparation; writing – original draft preparation; writing – review & editing. Matire Harwood: Writing – original draft preparation, writing – review & editing, supervision. Jamie-Lee Rahiri: Conceptualisation, project administration, formal analysis, methodology, data preparation, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review & editing, supervision.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank Pūtahi Manawa Healthy Hearts for Aotearoa New Zealand Centre of Research Excellence and Puhoro STEMM Academy for providing funding for a summer studentship for the lead Author. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Auckland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Auckland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Funding information

Ms. Maiea Mauriohooho is a Year 5 Medical Student at the University of Auckland. She undertook a summer studentship under the supervision of Dr. Rahiri which was funded by Pūtahi Manawa Healthy Hearts for Aotearoa New Zealand Centre of Research Excellence (CORE). The funders had no role in the study topic, design, analysis or dissemination and final reporting.

Conflict of interest

None to declare.