The Perth Emergency Laparotomy Audit

Abstract

Background

Emergency laparotomies (ELs) are associated with high mortality and substantial outcome variation. There is no prospective Australian data on ELs. The aim of this study was to audit outcome after ELs in Western Australia.

Methods

A 12-week prospective audit was completed in 10 hospitals. Data collected included patient demographics, the clinical pathway, preoperative risk assessment and outcomes including 30-day mortality and length of stay.

Results

Data were recorded for 198 (76.2%) of 260 patients. The 30-day mortality was 6.5% (17/260) in participating hospitals, and 5.4% (19 of 354) across Western Australia. There was minimal variation between the three tertiary hospitals undertaking 220 of 354 (62.1%) ELs. The median and mean post-operative lengths of stay, excluding patients who died, were 8 and 10 days, respectively. In the 48 patients with a prospectively documented risk of ≥10%, both a consultant surgeon and anaesthetist were present for 68.8%, 62.8% were admitted to critical care and 45.8% commenced surgery within 2 h. The mortality in those retrospectively (62; 31%) and prospectively risk-assessed was 9.5% and 5.2%, respectively.

Conclusion

This prospective EL audit demonstrated low 30-day mortality with little inter-hospital variation. Individual hospitals have scope to improve their standards of care. The importance of prospective risk assessment is clear.

Introduction

An emergency laparotomy (EL) is typically undertaken in an elderly, acutely unwell and high-risk patient. Surprisingly, there are relatively few EL studies, but those that exist consistently report a 30-day mortality of 15% and substantial variations in outcome and processes of care.1-5 Most of these studies were based on administrative data, with their inherent limitations. The UK Emergency Laparotomy Network (ELN) collected high-quality prospective data and reported a 30-day mortality rate of 14.9% and confirmed wide inter-hospital variation in outcomes and process of care.6

Evidence-based standards of care for patients undergoing an EL have been published by the National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths (NCEPOD) and others.7-9 Two studies have reported lowered mortality with introduction of a standardized perioperative bundle of care.10, 11 The National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) in England and Wales has reported that patients who did not have a preoperative documented risk assessment had a higher than expected 30-day mortality.12, 13

The outcome following ELs in Australia is unknown with no Australian multihospital study of ELs. A single hospital study included demonstrated 30-day mortality to be 12%.14

The aim of the Perth Emergency Laparotomy Audit (PELA) was to undertake a prospective multihospital audit to ascertain clinical outcomes following ELs in Western Australia (WA).

Methods

The reporting of this study conforms to the STROBE statement for cohort studies.15 Sixteen WA hospitals likely to perform ELs were invited to contribute to a consecutive 12-week prospective audit between August and October 2016. The primary end point was 30-day mortality. The secondary end points were length of stay (LoS) and compliance with evidence-based standards of care (Table S1).

Data collected included patient demographics, procedures, consultant presence, dates of admission, discharge, death and investigations including evidence of sepsis using Early Warning Score (EWS) and the quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA).16

Statistical analysis

Significant difference was defined as having P-value <0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide version 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients over the age of 18 undergoing a non-elective laparotomy were included. Non-elective laparoscopic procedures traditionally performed by laparotomy, for example omental patch of a perforated ulcer, open cholecystectomies, open appendiectomies performed through a midline laparotomy, incarcerated ventral hernias and unplanned returns to theatre if involving a procedure within the abdomen, were included.

Exclusion criteria included appendiectomies performed laparoscopically or via a Lanz incision, laparoscopic cholecystectomies and patients undergoing trauma, gynaecology, transplant and vascular surgery, unless performed as part of a general surgical EL. Patients having a scheduled return to theatre, such as planned washouts or removal of packs, were not included.

Data integrity

At each hospital, there was a responsible consultant and a surgical register coordinated data collection at each tertiary hospital. The PELA form was to be completed at the time of presentation to influence timeliness and process of care. Any form completed retrospectively was identified as such. To obtain complete EL ascertainment across WA, participating and the non-participating hospitals retrospectively reviewed their theatre records and submitted EL numbers and mortalities.

Privacy and confidentiality

Individual hospitals determined from their appropriate local committee whether participation in the PELA required ethical approval or was considered part of normal quality improvement audit activities. In the three tertiary hospitals, the responsible reporter entered anonymized data onto a spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) using drop-down menus to facilitate complete and accurate entry. Other hospitals returned anonymized forms to the principal investigator for entry on the combined database.

Preoperative risk assessment

Risk assessment for ELs has not been standard practice in WA. For pragmatic reasons, the Surgical Outcomes Risk Tool (SORT) was used.17

Risk-based analysis was performed separately for patients with a prospectively documented or a retrospectively calculated risk assessment.

Early warning signs of sepsis

Both EWS and qSOFA were recorded on admission, or at the time of first surgical review if under an alternative inpatient specialty. The PELA form required those with an EWS or qSOFA ≥2 to be considered septic and in addition those with a qSOFA ≥2 to be managed if their mortality risk was ≥10%.

Standards of care

Compliance with the Emergency Laparotomy Pathway Quality Improvement Care ‘bundle of care’ standards was assessed, excluding goal-directed care (Table S3).18

Non-operative cases

All patients who died under a general surgeon during the PELA period were extracted from the Western Australia Audit of Surgical Mortality (WAASM) and those presenting as an emergency with an acute abdomen did not have a laparotomy reviewed.19, 20

Results

Ten participating hospitals contributed audit data on 198 ELs in 194 patients during the 12-week period. The total number of eligible patients in the contributing hospitals was 260, with a completion rate of 76.2% (Fig. S1, Table 1). Not all forms were fully completed.

| TH 1 | TH 2 | TH 3 | SH | Other hospitals | WA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospectively risk-assessed | 38 | 20 | 43 | 24 | 11 | 136 |

| Retrospectively risk-assessed | 16 | 35 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 62 |

| ELs not audited | 26 | 5 | 28 | 3 | 0 | 62 |

| ELs in audited period | 80 | 60 | 80 | 27 | 13 | 260 – A354 – B |

| Ascertainment | 67.5% | 92.7% | 65.0% | 88.9% | 84.6% | 76.2% – A55.9% – B |

| 30-day mortality | 6 (7.5%) | 4 (6.7%) | 7 (8.8%) | 0 | 0 | 13/198 (6.6) – A 19/354 (5.4) – B |

| 90-day mortality | 8 (10.0%) | 6 (10.0%) | 8 (10.0%) | 0 | 0 | 18/198 (9.1) – A |

- EL, emergency laparotomy; PELA, Perth Emergency Laparotomy Audit; WA, Western Australia.

The six non-participating hospitals identified 94 ELs with two additional deaths (Fig. S1, Table 1).

Patient demographics and case mix

Among the 198 audited patients, the median age was 66 years, ranging from 21 to 95 years. One hundred and two patients (51.5%) were females and 33 (16.7%) were ≥80 years of age. Of the 198 patients, 90 (45.5%) were admitted through an emergency department, 66 (33.3%) were inter-hospital transfers and 42 (21.2%) were admitted under another specialty.

The median risk score was 5.6, with inter-hospital variation ranging from 3.9 to 7.1. Ninety-one of 198 (48.2%) patients were of low mortality risk (≤5%), 34 (18%) high risk (5–10%) and 64 (33.9%) of highest risk (≥10%). The median American Society of Anesthesiologists score was 3.

The surgical approach was open in 171 of 198 (86.4%) patients, conversion from laparoscopic to open in 14 (7.1%) patients, laparoscopic in 11 (5.6%) patients and laparoscopic-assisted in two (1%). The EL was performed as a primary procedure in 176 of 198 (88.9%) cases and a re-operation in 22 (11.1%) cases.

Of the 198 patients, the three most frequent procedures were colectomy (58; 29.3%), adhesiolysis (35; 17.7%) and small bowel resection (35; 17.7%) (Fig. S2).

Risk assessment

A prospective documented risk assessment was performed in 136 of 198 (68.7%) patients. A retrospective calculation of risk was assigned to a further 53, while nine were unable to be accurately assigned a retrospective risk score.

30-day and 90-day mortalities

The 30-day mortality of the audited ELs was 13 of 198 (6.6%) and 19 of 354 (5.4%) across WA. The 90-day mortality was 18 of 198 (9.1%) (Table 1).

The 30- and 90-day mortalities in those aged ≥80 years were 6 of 33 (18.2%) and 8 of 33 (24.2%), respectively.

There was minimal variation in 30-day mortality between the three tertiary hospitals (Table 1). All other contributing hospitals had no 30- or 90-day mortality.

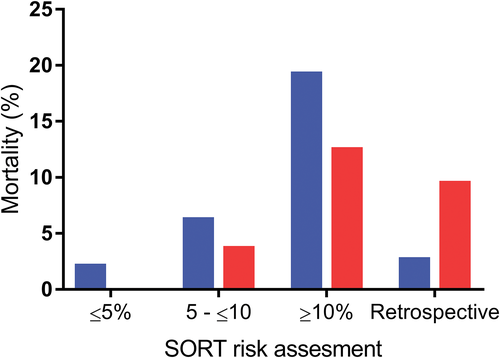

In those with a prospective risk assessment, the observed 30-day mortality was 7 of 136 (5.2%) and the predicted 30-day mortality based on SORT score was 5.7%. In those who had a retrospective risk assessment, the observed 30-day mortality was 6 of 63 (9.5%) and the predicted 30-day mortality 2.9% (Fig. 1). There was no statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality between the two risk assessment groups (χ2 = 0.251 and 1.00, P = 0.355 and 0.318 without and with risk factor adjustment, respectively). In the highest risk group, the 30-day mortality of those retrospectively assessed (5/16; 31.3%) was almost three times that of those prospectively assessed (6/48; 12.5%) (χ2 = 2.96; P = 0.09) (Fig. 1). These patients had lower compliance to the standards of care than those prospectively risk-assessed; only 25.0% (4/16) of patients with a SORT of ≥10 reached theatre within 2 h, compared with 45.8%, and consultant presence in theatre in 56% compared with 69%.

, median Surgical Outcomes Risk Tool (SORT) score;

, median Surgical Outcomes Risk Tool (SORT) score;  , 30-day mortality (%)).

, 30-day mortality (%)).Length of stay

The median and mean post-operative LoS, excluding patients who died within 30 days, was 8 and 10 days respectively.

Standards of care

Compliance with the standards of care is shown in Table 2.

| TH 1 | TH 2 | TH 3 | SH | Other hospitals† | WA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality risk ≥10% | ||||||

| Theatre access ≤2 h | <5 ELs | |||||

| Consultant anaesthetist | <5 ELs | |||||

| Consultant surgeon‡ | <5 ELs | |||||

| Both consultants‡ in theatre | <5 ELs | |||||

| Critical care admission post-operation | <5 ELs | |||||

| Mortality risk 5–10% | ||||||

| Theatre access ≤6 h | <5 ELs | |||||

| Consultant anaesthetist | <5 ELs | |||||

| Consultant surgeon‡ | <5 ELs | |||||

| Both consultants‡ in theatre | <5 ELs | |||||

| Critical care admission post-operation | <5 ELs | |||||

| Critical care discussion pre-operation | <5 ELs |

- † Groups with ≤5 ELs were not analysed.

- ‡ Those with an FRACS (Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons) qualification but not accredited as a consultant were not considered consultants.

- EL, emergency laparotomy; WA, Western Australia.

Sepsis and antibiotics

One hundred and twenty-seven of 198 patients were considered septic based on an EWS of ≥2, and/or qSOFA of ≥2. If a patient had a qSOFA of ≥2 (13/198 patients), the 30-day mortality was 23.1% (3/13). Seven of 13 (54%) with a qSOFA ≥2 had a risk score ≥10. Antibiotic administration data were incomplete and only recorded in 93 of 198 patients but in those considered septic, only 9 of 68 (13.2%) patients received antibiotics within 1 h.

Patient transfers and admissions under other specialties

Sixty-six of 198 (33.3%) were transferred from a referring hospital to one of the three tertiary hospitals. These patients had a similar mortality to those not transferred (6.1% and 6.8%) (χ2 = 0.04 and 0.10; P = 0.839 and P = 0.747 without and with risk factor adjustment, respectively) and similar median risk scores (5.7 and 5.3), respectively. Forty-two of 198 (21%) were initially admitted under another specialty with a 30-day mortality of 3 of 42 (7.1%).

Non-operative cases

Thirteen of 16 (81%) cases presenting with an acute abdomen who died without an EL met the inclusion criteria. Ten were aged ≥80 years (median: 88 years) and represented 23% (10 of 43) of all aged ≥80 years. Ischaemia (four patients) was the most frequent diagnosis. Nine (69.2%) died in ≤5 days.

Discussion

This is the first prospective Australian multihospital EL audit. The low 30-day mortality and minimal inter-hospital variation compares favourably with previous studies.6, 10-12 The low 30-day mortality is in keeping with the short LoS, this being a surrogate marker for uncomplicated clinical care and efficient management.

The PELA did include appendicetomies through a midline incision (two patients), open cholecystectomies (seven patients, one death with six of seven having a risk >5%; mean: 8.2%), and large incarcerated ventral hernia repairs.13 If these procedures were excluded as they were in the NELA, the 30-day mortality was 6.8%.

When comparing with the NELA, 30-day mortality was lower in the PELA within all risk groups, as well as in the age group over 80 (24% and 18.2%, respectively). However, there was a lower proportion of patients in the highest risk group in PELA with 34% compared to 41% in the NELA. The 90-day mortality in the PELA and NELA was 9.1% and 15.3%, respectively.6, 12

A unique aspect of this study has been the ability to link it to the WAASM and identify patients admitted with an acute abdomen but who did not have an EL.19, 20 Since WAASM commenced, the proportion of general surgical emergency patients who die having not had an operation, including an EL, has almost doubled. The low 90-day mortality supports this suggestion – that in WA fewer patients undergo EL only to succumb within 90 days from medical co-morbidities. Non-operative cases have not been included in any previous EL studies but should be included in future prospective EL audits.

The WA hospitals did not meet most bundle of care standards (Table 2).10, 11 The introduction of this bundle of care has resulted in a significant reduction in 30-day mortality with other improvements in care.10, 11 Failures in this study included poor theatre and post-operative critical care access, especially in the highest risk patients, and very low early antibiotic administration. Introduction of a standardized perioperative package may not further reduce this low mortality, but may reduce post-operative complications, overall and ICU LoS and costs.

A key observation in this study was that the 30-day mortality in those who had a prospectively documented risk assessment was lower than those in whom it was retrospectively calculated (5.2% and 9.5%, respectively). This was despite the median SORT score in the group who were not risk-assessed being lower that in the groups who were risk-assessed (2.9% and 5.7%, respectively). The observed mortality in those not risk-assessed was triple the expected mortality (9.5% and 2.9%, respectively). These observations are in keeping with the NELA who reported that the observed 30-day mortality in those not risk-assessed was similar to their high-risk group and they were less likely to receive other key process measures.

Embedding a risk assessment into the theatre booking process so that it cannot be finalized until completed has been shown to increase compliance.21 High-risk patients would then be identified and that would trigger an agreed care pathway that alerts staff and hospital facilities and ensure they receive other key process measures.

The PELA used EWS and qSOFA as the trigger for the diagnosis of infection or sepsis. The timing of antibiotic administration was poorly recorded, but in those in whom it was recorded the 1-h standard was met in <20%. In this audit, a qSOFA ≥2 was associated with an almost fourfold increased risk of mortality, yet only 16.7% of patients received antibiotics within 1 h. The ability of qSOFA to discriminate 30-day mortality was much greater than the traditional EWS. This is the first EL audit to incorporate qSOFA and further studies in this setting are required.

A limitation to the PELA is that it only captured audit data on 76.2% of the ELs in the participating hospitals (similar to the NELA), and only for 10 of 16 WA hospitals that undertake ELs. Whilst an EL might have been missed in the retrospective review of theatre records, the checking of hospital and other death records makes it unlikely any deaths were overlooked.

Whilst the low 30-day mortality in WA is encouraging, this cannot be a substitute for nation-wide Australian data. There are important differences between Australian and other health systems, so extrapolation from UK data is unlikely appropriate. Variation of surgical care in Australia has been well documented and is likely to exist following ELs.22 Although administrative data are available through the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, it will be of limited value as it will not include preoperative risk assessment or document adherence with a bundle of care, both of which have now been shown to improve outcome. There is a compelling case for an Australian NELA. This should include patients with an acute abdomen who do not undergo EL.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.