Our experience in using telehealth for paediatric plastic surgery in Western Australia

Abstract

Background

Western Australia accounts for one-third of Australia's total land mass. Princess Margaret Hospital is the only dedicated plastic surgery tertiary referral centre providing services to over 500 000 children across the state. The aim of this study is to share our experience using telehealth for service provision and delivery of care in a geographically challenging setting.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted, and data were extracted from patients’ notes. The time period was from January 2014 to 31 December 2015 and included all patients registered for plastic surgery telehealth service.

Results

There were a total of 194 rural patients (66 males and 128 females), 26 of whom were elective cases. A total of 358 telehealth follow-up consultations were conducted for the 194 patients during the study period. A total of 10 patients were managed via telehealth alone without a clinical review in Perth; 24 patients had their first clinical review in Perth and further follow-up via telehealth, and 99 patients were post-operative cases. Case load ranged from skin lacerations to complex soft tissue and bony injuries as well as elective hand and craniofacial post-operative follow-up cases. Telehealth service was utilized mainly for post-operative follow-up.

Conclusion

It is our experience that telehealth provides access to Specialist Plastic Surgery service across the state. We utilize telehealth for a wide scope of functions. Patients in rural areas are managed in their home environments, reducing financial and psychosocial burden with the option of transfer to Princess Margaret Hospital should an intervention be required.

Introduction

‘Telehealth’ is the use of telecommunication technologies for exchanging medical information for the purpose of diagnosis, consultation, treatment and teaching.1 Advancements in telecommunication technology and digital data transmission, along with Telehealth Medicare incentives in 2011, have seen an increase in the provision of expertise not available ‘on-site’.2

Western Australia covers an area of more than 2.5 million square kilometres, accounting for one-third of Australia's total land mass.3 Tertiary care is centralized in Perth, its capital city, with limited regional infrastructure and specialist services available to relatively small rural populations over huge distances. As a result, patients can be transferred from as far away as the Cocos Islands, 2900 km from Perth.

Western Australia's only tertiary paediatric referral centre, Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH), provides plastic surgery services to over 500 000 children across the state.4 Patients and their families travel great distances, sometimes more than 24 h, to access tertiary plastic surgical care. Telehealth offers the opportunity to deliver specialist services across the state with care equal to that available to patients in city, providing convenience to families, reducing outreach clinics and supporting rural health professionals.5-7

PMH Telehealth Service first commenced in 2003 with the caseload including both elective and trauma plastic surgery patients. The aim of this study was to share our experience using telehealth for service provision and care delivery in a geographically challenging setting.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted over a 24-month period (1 January 2014 to 31 December 2015). Plastic surgery patients who utilized telehealth services over this time period were included in the study. Ethics approval was obtained via PMH's Ethics and Governance office (GEKO 10495 clinical audit process).

The following information was collected: demographic details including age, address, referring institution, date of injury and referral; mode of transport; date of first review; date of operation; number of telehealth follow-ups and final outcome. Telehealth consultations were booked to run simultaneously with Plastic Dressings Clinic (PDC) at PMH to provide access to plastic surgery clinicians and hand therapists.

Two dedicated PMH telehealth coordinators provided logistic support, making telehealth convenient and easy to access for PMH staff. Besides liaising with health professionals both at PMH and the end site, they also build relationships with stakeholders at end sites to promote their engagement in ongoing telehealth services. End-site health professionals who attended the consultations included doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

A telehealth booking form illustrating particular staff requirement as well as a radiology request form (if required) were filled and faxed to the end-site health facility. Real-time videoconferencing was carried out via Polycom HDX 6000 device (Polycom, San Jose, CA, USA) at PMH with end sites utilizing the same or older models.

Radiology data were transferred onto the IMPAX platform for viewing. High-resolution digital photographs of the wound were transferred electronically to a secured telehealth email (Department of Health Outlook WebApp) to provide detailed wound images during videoconferencing.

The telehealth coordinator established a video link from one of the clinic rooms during PDC hours with the help of the mobile equipment (Fig. 1). The plastic surgery clinician has access to patient notes and high-resolution digital photographs as well as X-ray via the IMPAX system (Version 6.5.3.1509), if required.

The consultation at the end site was attended by the patient, their guardian and a nurse with or without a physiotherapist or an occupational hand therapist depending on the requirement and availability. The camera at the end site could be remotely controlled to focus on a certain area of the body for clarity when required.

The patient is instructed to carry out certain tasks (if required), and the nurse, guardian or the allied health personnel provide assistance. If prescriptions are required, these are provided by the end-site health professionals or faxed from PMH. The nurse is instructed on the dressing regime, and further follow-up plans are organized either via telehealth or in PMH depending on the clinical condition.

Results

A total of 194 plastic surgery patients (168 trauma and 26 elective) were reviewed via telehealth during this study period. There were a total of 128 female and 66 male patients. Average age was 8 years.

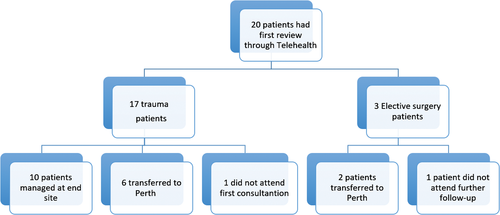

A total of 20 patients had their first plastic surgery consultation via telehealth. Their follow-up management is show in Figure 2. There were a total of 17 trauma patients, 10 of who were managed locally (one patient for ligamentous injury, five patients for closed fracture and four patients for dressings) without a transfer to Perth.

Seven patients required transfer to Perth (one patient did not attend). Out of the six patients transferred, one patient required fracture manipulation under anaesthesia; one patient required a formal assessment in Plastic Surgery Clinic before continuing with non-surgical management of their fracture, and the remaining four patients required surgical repair of lacerations and drainage of abscess.

Over 80% of the trauma presentations were referred from rural hospitals. The remaining 20% were from rural GP clinics, nursing posts and Aboriginal Health Services. The majority of patients were transferred via commercial flights, some via Royal Flying Doctors Service based on clinical urgency.

Trauma patient distribution is shown in Table 1. Elective surgery cases, as shown in Table 2, included three preoperative assessments and 24 post-operative follow-up assessments. One patient was lost to follow-up.

| Trauma cases | Number |

|---|---|

| Infections | |

| Skin | 13 |

| Osteomyelitis | 3 |

| Paronychia | 3 |

| Septic arthritis | 1 |

| Fractures | |

| Closed | 51 |

| Open | 8 |

| Soft tissue hand injuries | |

| Volar plate | 2 |

| Thumb ulna collateral ligament partial tears | 2 |

| Wounds | |

| Nailbed injuries | 20 |

| Lacerations | 30 |

| Abrasions | 3 |

| Dog bites | 9 |

| Amputations | |

| Tamai zone I | 14 |

| Tamai zone IV | 2 |

| Toes | 3 |

| Chronic dislocations | 2 |

| Compartment syndrome | 1 |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 1 |

| Total | 168 |

| Elective surgery cases | Number |

|---|---|

| Preoperative | |

| First webspace contracture | 1 |

| Macroglossia | 1 |

| Forearm lesion | 1 |

| Total | 3 |

| Post-operative | |

| Lesions | 7 |

| Congenital hands deformity | 3 |

| Trigger digits | 4 |

| Hand contracture release | 4 |

| Toe polydactyl | 1 |

| Frenulum release | 1 |

| Scar revision | 1 |

| Craniosynostosis | 1 |

| Cleft lip and palate | 1 |

| Radial nerve palsy | 1 |

| Total | 24 |

A total of 358 telehealth follow-up consultations were conducted for the 194 patients during the study period; 86 post-operative patients were kept in Perth for their first clinical review after discharge from PMH prior to telehealth follow-up. Some patients required more than one PDC visit, as shown in Table 3.

| Number of reviews in PMH prior to telehealth | Trauma patients | Elective surgery patients |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 81 | 12 |

| 1 | 53 | 7 |

| 2 | 6 | 2 |

| 3 | 6 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 1 | 0 |

| 25 | 0 | 1 |

| Did not attend first follow-up appointment | 3 | 1 |

| Did not have operation | 1 | 1 |

| Did not require transfer to Perth | 10 | 0 |

- PMH, Princess Margaret Hospital.

Follow-up in PDC was mainly for post-operative wound review and dressing change. This was also to reassure that patients were progressing well as expected and were less likely to require further plastic surgical intervention before discharge to telehealth follow-up.

Telehealth was used mainly for wound review, range of movement review, hand therapy, scar management education and X-ray review. Less commonly, telehealth was used for plaster check, histopathology and haematology result follow-ups.

Out of the 194 telehealth patients, 51 were transferred to Perth for reassessment and further management after commencing telehealth follow-up. Out of 51 patients, 32 were planned return; for services not available rurally (K-wire removal and division of thenar flaps). The remaining 19 were transferred due to changes in their clinical condition, as shown in Table 4.

| Reason patient brought back to Perth | Number |

|---|---|

| Removal of K-wires | 27 |

| Division of thenar flap | 5 |

| Difficulty accessing rural and remote hand therapy | 4 |

| Fracture slipped requiring reassessment | 6 |

| Wound concerns | 2 |

| Developed fixed flexion deformity | 2 |

| Developed swan neck deformity | 2 |

| Developed mallet deformity | 1 |

| Ongoing pain post-completion of volar plate protocol | 1 |

| Vomiting and wound discharge post-spring cranioplasty | 1 |

| Total | 51 |

A total of 48 patients were lost to follow-up. A total of 38% (18 patients) were lost to follow-up along their treatment journey. The remaining 62% (30 patients) did not attend their final consultant clinical review in Perth. We believe this loss to follow-up reflects the family's decision not to travel to Perth given a good clinical outcome (as documented in patient's previous follow-up notes) and the associated inconveniences with travel.

Discussion

Western Australia faces significant geographical challenges in the provision of paediatric plastic surgery care. Despite Kimberley region being closer to the Northern Territory, patients are flown to Perth for treatment, requiring a 3-h direct flight with the Royal Flying Doctors Service or longer via commercial flights.10

Telehealth offers an opportunity to address this challenge. Patients from rural and remote areas can access plastic surgical care similar to that in the city centre with reduced barriers of distance and cost.

A total of 65% of patients who were initially assessed via telehealth continued to be managed remotely. This is particularly pertinent in the paediatric population when a transfer to Perth requires a parental escort and the potential separation of the family unit. In Western Australia, permanent rural and remote area patients and their escorts are provided a subsidy by the Patient Assisted Travel Scheme for travel and accommodation costs to attend specialist care not available locally.8 Although financially supported by the Royalties for Regions programme, it can still pose a significant financial and psychosocial burden and a disruption from life and work for families to travel great distances for a clinic appointment.5, 6, 8

Rural health providers who may not have had adequate experience in wound and fracture management can obtain verbal advice from plastic surgery health professionals based in a tertiary centre.

For example, a 14-year-old female was transferred via commercial flight for assessment in PDC due to a lack of rural X-ray facilities and poor compliance with examination assessment via telehealth. She was initially referred by a rural GP for generalized upper limb pain 6 weeks post-blunt force trauma.

X-rays performed on arrival showed no acute fractures, and there were no clinical concerns. She was reviewed by acute pain service specialists and commenced on a physiotherapy regime before discharge from hospital. Subsequent reviews via telehealth showed significant improvement, both for pain and movement. It is pivotal that rural health providers feel supported and comfortable to manage the patients with remote advice in a shared care model. We had a low threshold for transfer to PMH if rural health professionals expressed concerns regarding ongoing shared management.

Telehealth is used infrequently by other specialties at PMH. This presents a problem for the patients when they are co-managed with another treating team. A 4-year-old girl with post-operative osteomyelitis required weekly travel to Perth for infectious disease team review, creating significant inconvenience to her and her family.

We have used this opportunity to engage other specialties in telehealth provision across PMH. Telehealth usage is gradually increasing as both clinicians and patient families become more comfortable using this service. In the past 2 years alone, the use of telehealth in our service has increased by 30%, and the trend will continue to rise.

Another barrier for telehealth is access to the provision of specialized hand therapy services in the rural area. Complex hand deformities have their first review in PMH to allow for ‘hands-on’ clinical assessment and surgical planning.

Ongoing follow-up is preferentially managed via telehealth until the consultant surgeon's clinical review. However, specialized hand therapists are in short supply rurally. A 5-year-old child's post-tendon transfer required transfer to Perth for assessment and plaster adjustment. Despite the best efforts of PMH and rural telehealth coordinators to provide management for patients at home, at times, patients and their families are required to attend PMH for ongoing management when resources are not available remotely.

There are cohorts of patients for whom telehealth is not appropriate. These include patients requiring complex multidisciplinary team input, such as patients with cleft lip and palate, congenital hands and patients whose clinical conditions have changed requiring a transfer to PMH.

The benefits of telehealth are enriched through the opportunities provided via clinical photography, radiology imaging, laboratory results and real-time videoconferencing.7 Clinical images are transferred to a designated Department of Health secured email. The images are then printed, and a hard copy is placed in the patient's medical file before email deletion. These notes are stored in the Medical Records Department with all PMH patient notes.

Our service has a cautionary approach towards discharging patients back to rural and remote locations due to concerns regarding compliance with therapy and loss to follow-up. A total of 9% of patients were lost to follow-up during their treatment journey and 15% of patients at their final consultant review.

We have utilized the convenience and versatility of telehealth to develop working connections with rural communities and provide convenience to families to improve compliance and attendance at ongoing reviews.

Of our 27 K-wire removal patients, 26 were transferred to Perth for the procedure. One patient had wires removed locally by an orthopaedic surgeon at an outreach clinic in the rural town. Although the task of removing K-wires is possible in a rural and remote setting, appropriate clinical assessment needs to be undertaken by experienced clinicians prior to the procedure. It is also important that patients and their parents feel comfortable and safe to be managed at home.

However, with increasing number of patients using telehealth facilities, the potential to upskill local staff to provide a semi-invasive procedure, such as K-wire removal, via telehealth guidance is an exciting new frontier. We have also used telehealth to educate rural heath providers on the clinical examination of the hand, plaster application techniques, hand therapy exercises and scar management.

Our service underutilizes the potential of telehealth. Only 26 elective surgery patients were managed through telehealth over the 24-month period. A total of 86% of all closed fractures were transferred to Perth, of whom only 55% required manipulation under anaesthesia or surgical fixation. The remaining 45% could have been managed via telehealth.

In future, the majority of closed fractures could be first clinically assessed via video link with radiology images before deciding on transfer to PMH.

As many benefits of telehealth are realized, and health professional become more familiar with its use, the scope of telehealth will certainly expand.6, 9 This has been shown by PMH Burns Service, which provides a multidisciplinary telehealth service for triage and management of burns patients in rural and remote areas. Only patients who require further medical intervention are transferred to PMH. This significantly reduces the cost of healthcare provision whilst maintaining high standards of care.

Conclusion

There is increased scope for telehealth in our service than its current usage, with the potential for preoperative review as well as initial trauma assessment and further management. As health moves forward in the digital era, telehealth provides a useful adjunct for provision of care.

Telehealth is an adaptive medium of communication capable of being tailored to meet clinical requirements. Our service operates telehealth for patient communication, review of imaging and laboratory investigations, rural health professional education and hand therapy advice.

The development of community links improves rural health professionals’ engagement and patient compliance. Telehealth communication is not a barrier to review in a tertiary centre, especially if there are any clinical concerns from rural or tertiary health professionals or patients’ preference. Suitable patients are managed in their home environments, reducing financial and psychosocial burden with the option of transfer to PMH should an intervention be required or the clinical condition changes, as shown in this study. Moreover, our engagement with other tertiary clinical teams has allowed them to see first hand the benefits offered by telehealth service for their rural patients.

Telehealth is a medium for rural and remote health professionals to work in partnership with tertiary plastic surgery services to build a shared care model, offering significant equity and financial advantages.

Our experience demonstrates that telehealth is an opportunity for convenient and timely access to guide patient management, providing tertiary plastic surgery specialist services across the state with care equal to that available to patients in city centres.

Acknowledgement

PMH Plastic and Reconstructive Service is supported by the PMH Telehealth Service, clinic nurses and hand therapists.