Reinterpretation of radiological findings in oesophago-gastric multidisciplinary meetings

Abstract

Background

This study aims to objectively evaluate the clinical impact and significance of the multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT) in the management of oesophago-gastric malignancies in a tertiary institution.

Methods

A prospective observational study was designed to examine the role of MDT in the interpretation of computerized tomography (CT) scans in oesophago-gastric malignancies. The MDT reporting of CT scans were compared with the ‘pre-meeting’ formal report of the scans. ‘Pre-meeting’ CT reports are provided by internal institutional or independent radiologist. The frequency and significance of any reporting variance is examined.

Results

Of the 34 patients discussed, 13 patients (38%) had variations to the formal radiological report. This led a modification of disease stage in seven patients (21%) and change in diagnosis in three patients (9%). This had a major impact in nine patients (26%) of which seven patients (24%) had modification in treatment as a result of imaging reinterpretation.

Conclusion

This study provides preliminary quantative evidence of the utility and importance of the MDT process in the management of oesophago-gastric malignancies. This has potential significant implications for basing patient treatment on isolated reports outside of MDT and supports this process as a standard of care.

Introduction

In the contemporary era of cancer management, the multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT) is almost universally accepted as a standard of care. This process allows integration of all available information and it is an effective and efficient method of patient management.1

Despite subjective impression of utility, there is limited objective data in the literature demonstrating direct clinical benefit from the MDT process. Our own individual anecdotal experience suggested that clinical benefit is derived from the interpretation of radiological investigations through integration of all clinical information in the MDT. We set out to evaluate the role of MDT in reinterpretation of computerized tomography (CT) radiological images; the degree this impacts on both the staging of disease and clinical outcome.

Method

With institutional ethics approval, a prospective observational study was conducted according to the standards outlined by the committee. Over six consecutive MDT meetings, data was collected for consecutive patients with a new diagnosis of oesophago-gastric cancer.

The process of MDT involved the treating clinician presenting the clinical details of the case and review of pathology and staging investigations performed. Standardized staging in the institution included endoscopy, high-resolution CT scanning, positron emission tomography scanning, laparoscopy and variably, endoscopic ultrasound. After clinical presentation and pathology review, the MDT radiologist is then invited to comment on CT imaging. After the process of deliberation of all other available information, the MDT radiologist is often able to provide further input and clarification in interpretation of the CT images, either voluntarily or upon direct questioning from the team members.

CT imaging reviewed may or may not have been performed at the study institution and were all reported prior to the meeting by independent radiologist in the usual manner. The MDT radiologist had access to this report.

The MDT members were blinded to the timing of the study. A single clinician assigned as a ‘data collector’ was blinded to the ‘non-MDT’ or ‘formal’ imaging report. The data collector recorded imaging interpretations by the MDT radiologist as well as clinical decisions that arose from the subsequent process of discussion.

At the end of the study period, the MDT radiologist's findings were compared with the pre-meeting formal CT report. Variances noted in each case were categorized in terms of significance and clinical impact by two authors independently and then final decision by consensus. The information was tabulated and filtered on Mircosoft Excel 2007. Because of small numbers, Fisher's exact test was used for nominal variables.

Results

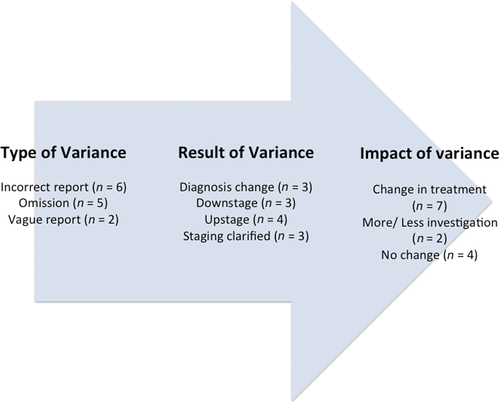

In six consecutive MDT meetings, 34 eligible patients were discussed. Of these, 13 patients (38%) had findings at variance to the original radiology reports (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Flow chart of variances and impact in 13 patients.

| Diagnosis | Type of variance | MDT interpretation | Clinical significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumour | Incorrect diagnosis | Tumour location clarified to be in small bowel, not stomach. | Surgery offered for bleeding despite patient co-morbidities. |

| Gastric lymphoma | Incorrect diagnosis | Diagnosis of subtle biliary obstruction upon comparative imaging. | Subsequent investigation and tissue biopsy confirmed lymphoma. Patient offered chemotherapy. |

| Distal gastric cancer | Incorrect staging | Staged as early gastric cancer. | Upfront surgery rather than neo-adjuvant treatment. Histological stage concordant. |

| Oesophageal SCC | Incorrect staging | Nodal disease within resectional field and not deemed metastatic. | Surgery performed post neo-adjuvant treatment. |

| Distal gastric cancer | Incorrect staging | Station 6 node (curative) rather than Station 14 node (non-curative intent). | Surgery undertaken and confirmed that station 6 node was within field of resection. |

| Oesophageal adenocarcinoma | Incorrect staging | Nodal disease more advanced than reported. | Neo-adjuvant therapy undertaken prior to surgery. |

| Proximal gastric cancer | Omission of staging | Peritoneal nodule adjacent to spleen led to diagnostic laparoscopy. | Biopsy confirmed advanced stage. Patient did not undertake definitive surgery. |

| Oesophageal SCC | Omitted finding | Pulmonary nodules clarified as benign. | No change in treatment. |

| Oesophageal SCC | Omission of staging | Highly likely tumour invasion of major vascular structures. | No change in plan of treatment. Definitive chemo-radiation therapy. |

| Distal gastric cancer | Omission of staging | Distal gastric tumour with pyloric extension. Concerns of local invasion of adjacent structures unfounded. | Distal radical gastrectomy without the need for a whipples. Histologically confirmed clear margins of resection. |

| Oesophageal adenocarcinoma | Omission of staging | Staging and ambiguity of nodal disease clarified. | No change in plan of treatment. Patient had neo-adjuvant treatment followed by surgery. |

| Proximal gastric cancer | Ambiguous report | Para-aortic nodal disease confirmed. | Due to advanced nodal stage, no change in palliative chemotherapy offered. |

| Pancreatic mass | Ambiguous report | There were radiological features of pancreatic neoplasm. | Further investigation was deemed unnecessary. Patient had upfront surgery. |

- SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

In comparing MDT radiology reports to non-MDT reports, there were 6 (18%) with incorrect diagnosis or staging, failure to mention or omission of clinically relevant findings in five patients (15%) and unclear reporting in two patients (6%).

This led to a modification of disease stage in seven patients (21%) and change in diagnosis in three patients (9%). The remaining three patients (9%) had clarification of the stage of disease without clinical impact.

These variations resulted in a major clinical impact in nine patients (26%). Seven patients (24%) had modification to planned treatment including three changing from palliative to curative intent and two patients had a change in subsequent work-up investigations (Table 2).

| Change in treatment | Number of patients (n = 7) |

|---|---|

| Intent of treatment changed from palliative to curative | 3 |

| Intent of treatment changed from curative to palliative | 1 |

| Treatment type and methodology | 2† |

| Surgery offered despite high risk | 1‡ |

| Change in subsequent investigation | Number of patients (n = 2) |

| Resulted in surgery | 1 |

| No difference in final treatment | 1 |

- †Treatment methodology – 1 was offered chemotherapy for lymphoma, 1 was offered neo-adjuvant treatment prior to surgery. ‡1 patient offered surgery despite high risk of anaesthesia – patient initially thought to have gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor. MDT review suggested gastrointestinal stromal tumor was located in small bowel. Concerns were raised regarding bowel obstruction and bleeding.

Variations occurred regardless of whether scanning was performed at the tertiary institution (n = 7; 35%) or externally (n = 6; 43%). In the group where there was a major clinical impact (n = 9), the proportion of report variation was again similar between institutions (tertiary centre, n = 5 versus external, n = 4; P = 1.0).

Discussion

The MDT has become an established process in modern cancer care. Subjective benefits of collegiality and improved communication between specialists involved in the care of cancer patients are anecdotally evident.2-5 Some studies have demonstrated improved efficiencies in care6-8 and patient satisfaction.6, 7 However, direct clinical benefits and the mechanisms for this have only been studied in limited fashion. Benefits in revised diagnoses and treatment plans have been published9-11 but mechanisms for this heterogeneously assigned. A study from China12 documented almost 70% change in planned management in oesophago-gastric cancer by creating uniform guidelines in an MDT process but this was in an environment of widely disparate practice and may have little direct relevance to care in Australia. In oesophago-gastric cancer, MDT integrated staging has been shown to be more accurate than staging using isolated investigations13 but effects of the MDT on imaging interpretation was not detailed.

This study detailed the effect of the MDT on interpretation of CT imaging when compared with the isolated CT report and the clinical impact of any variation. This allowed direct evaluation of a single parameter to isolate a mechanism of effect of the MDT.

We found that variations existed between MDT reinterpretation and external reports in 38% (13 patients). This had a significant clinical impact in 26% of patients including, importantly, a change in treatment plan from palliative to curative in three patients. These substantial figures are consistent with the results published by Loevner and co-workers14 who undertook a similarly designed study limited to head and neck cancers.

Variations often took the form of precise anatomical localization of suspicious lymph node stations or potential involvement of primary tumours with adjacent structures. On occasion, other sites of disease not previously reported or other pathologies that impacted on treatment/investigation were important additional findings.

Having a dedicated and consistent radiologist at the MDT is important. The interaction between radiologist and clinicians often results in the focus of certain disease features that alter the stage or treatment intent. It may be argued that the variation seen was due to the presence of a specialist radiologist rather than the MDT process as such. In this regard however, several points must be considered. Firstly, the omission of critical information in the pre-MDT imaging reports reflects a ‘real-world problem’ of heterogeneous quality of reporting. Many patients with a new diagnosis of cancer in the community have CT scans performed in a variety of settings. Indeed, patients in this study had scans in tertiary institutions, (including the study institution) and at private community facilities. While the images may be of high quality, heterogeneity of reporting means that interpretation may not be sufficiently appropriate to enable sound clinical decisions In this ‘real-world scenario’, the interpreting radiologist may not have specialized interest, nor have all of the clinical detail of the case. This is the advantage that the MDT provides. Having the regular availability of an interested and specialist radiologist rather than relying on isolated reports from a heterogenous group of radiologists is very much the intention and part of the MDT process itself. Secondly, the ongoing interaction between the radiologist and the team members develops expertise for the radiologist who becomes more familiar with thinking patterns and treatment approaches of clinicians and thus focuses on key factors in the imaging relevant to this. Finally, while not formally reported in our results, we found that after making initial comments, quite often, the radiologist would go back to the films either as a result of the ensuing discussions or because of direct questioning by team members and further interpretation contributed to variance.

This study has several limitations. Although prospective and consecutive in nature, it is small in numbers and as such is preliminary in nature. Nonetheless, the results strongly support the hypothesis that MDT interaction frequently results in reinterpretation of radiology and this may have a significant clinical impact in some patients. Comparing longer term oncological outcomes was beyond the scope of the study. The small numbers preclude this. Additionally, a control group treated outside of an MDT environment would be required and we do not regard this as an acceptable ‘standard of care’.

Preoperative staging was not correlated to final pathological stage to determine accuracy of reports. However, this was not an outcome measure of the study, its main aim being the effect on the planning process of treatment. Hence such a comparison is less relevant, particularly since neo-adjuvant therapy (used in most cases) likely alters final pathological stage.

This study was not designed to investigate the individual components (discussion versus positron emission tomography versus laparoscopy, etc.) of MDT upon radiology findings. Rather, it demonstrates the effect of MDT process in its entirety in the interpretation of radiology imaging.

Critics of MDT point to the benefits of having an expert surgeon referring the patient to an expert oncologist and radiotherapist, with each doctor meeting the patient and family, rather than just reviewing slides and X-rays. We agree that the MDT does not take the place of expert clinical assessment and judgment. It does however allow those experts to gather in a specific meeting to review the clinical material available and develop a consensus strategy with accurate reviewed imaging information. It does not preclude the subsequent individual expert clinical assessment, which, at least in our practice, proceeds from that meeting and is integral to overall care.

This study adds to the emerging objective data that the MDT process has relevant clinical effect and supports the notion that MDT meetings should be a central component of care in oesophago-gastric cancer.