The impact of extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of young patients with vasculogenic mild erectile dysfunction: A prospective randomized single-blind, sham controlled study

Abstract

Background

Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) for the treatment of vasculogenic erectile dysfunction (ED) has emerged as a promising method directly targeting the underlying pathophysiology of the disease.

Objectives

To compare outcomes in ED patients after ESWT and placebo treatment.

Materials and methods

Prospective randomized placebo-controlled single-blinded trial on 66 patients with mild ED. The study comprised a 4-week washout phase, a 4-week treatment phase, and a 48-week follow-up. Inclusion criteria included age between 18 and 75 years and diagnosis of mild ED (IIEF-EF score = 17–25) being made at least six months prior to study inclusion and being confirmed by Penile Doppler ultrasonography (US) at baseline examination. Efficacy endpoints were changes from baseline in patient-reported outcomes of erectile function (International Index of Erectile Function domain scores [IIEF-EF]), as well as erection hardness and duration (Sexual Encounter Profile diary [SEP] and Global Assessment Questions [GAQ]). Safety was assessed throughout the study.

Results

A total of 66 enrolled patients were allocated to ESWT (n = 44) or placebo (n = 22). Mean age of ESWT and placebo group was 42.32 ± 9.88 and 39.86 ± 11.64 (p = 0.374), respectively. Mean baseline IIEF-EF scores of ESWT group and placebo were 20.32 ± 2.32 and 19.68 ± 1.55 respectively (p = 0.34). At 3-months follow-up, mean IIEF-EF scores were significantly higher in ESWT patients than in placebo patients (23.10 ± 2.82 vs. 20.95 ± 2.19, p = 0.003), and IIEF-EF scores of ESWT patients remained high during the 6 months (22.67 ± 3.35 vs. 19.82 ± 1.56) follow-up. The percentage of patients reporting both successful penetration (SEP2) and intercourse (SEP3) in more than 50% of attempts was significantly higher in ESWT-treated patients than in placebo patients (p = 0.001). A minimal clinically important difference between the IIEF = EF baseline and 3-months follow-up was found in 74% of ESWT and 36% of placebo. No serious adverse events were reported.

Discussion and Conclusion

ESWT significantly improved the erectile function of relatively young patients with vasculogenic mild ED when compared to placebo and the beneficial effect of this treatment up to 6 months. These findings suggest that ESWT could be a useful treatment option in vasculogenic ED.

1 INTRODUCTION

Erectile dysfunction (ED), the persistent inability to attain and maintain an erection sufficient for sexual intercourse, is highly prevalent in middle-aged men with vascular risk factors and profoundly affects their quality of life.1 For the past decades, oral phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors, intracavernosal injections, intraurethral agents, and vacuum erection devices have been used for treatment ED. If these alternatives fail or are unacceptable due to adverse effects, penile prosthesis implantation is the final option.2

All of these therapies available share the same limitations. Treatments need to be applied at the appropriate time prior to sexual intercourse and are only temporarily effective except penile prosthesis implantation. Importantly, none of these treatments target the underlying ED pathophysiology. PDE5 inhibitors may have revolutionized ED management, but are not always effective in men with penile vascular flow impairments after advanced diabetes or cardiovascular disease.3

In recent years, low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has been used for the treatment of various disorders for which an improvement of blood supply has been found to be beneficial. ESWT shock waves can be focused in such a way as to noninvasively target the selected organ, interacting with the tissue and causing mechanical stress, which in turn triggers the release of growth factors and neovascularization. However, the exact mechanism of ESWT is still unknown.4 Consequently, ESWT has been successfully used for the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders,5 myocardial infarction,6 non-healing wounds,7 and ED.8

Several studies on ED have shown encouraging results of low-intensity ESWT for patients with mild to severe ED. ESWT has been demonstrated to have positive physiological effects on erectile function in both patients who had responded to PDE5 inhibitors before9-11 and poorly responding patients.12-14 Accordingly, the European Association of Urology guideline on male sexual dysfunction15 listed ESWT as an ED treatment option after PDE-5 inhibitors and vacuum erection devices. To the best of our knowledge, this device (DUOLITH ® SD1) has not been studied as frequently as other devices in a randomized setting in patients with mild ED.

Here, we report the results of a prospective randomized placebo-controlled single-blinded a single-center trial on 66 patients with mild ED of vascular origin. The study consisted of 4-week washout phase, a 4-week treatment phase, and a 48-week follow-up. It aimed at assessing the efficacy and safety of ESWT versus placebo, thereby confirming the results of previous studies.9-14 Efficacy endpoints were changes from baseline in patient-reported outcomes such as the International Index of Erectile Function domain scores (IIEF-EF), the Sexual Encounter Profile diary (SEP), and the Global Assessment Questions (GAQ) at the 3-month follow-up.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design and patients

Our study was a prospective randomized placebo-controlled single-blinded trial conducted between July 2016 and February 2018 at a single center. Inclusion criteria included age between 18 and 75 years and diagnosis of mild ED (IIEF-EF score = 17–25) being made at least six months prior to study inclusion and being confirmed by Penile Doppler ultrasonography (US) at baseline examination. The EAU guideline suggest a cutoff value of peak systolic velocity >30 cm/s, end-diastolic venous flow <3 cm/s, and resistance index >0.8 to be considered normal.2 Hence, the patients who had normal Penile Doppler US were excluded from the study. Patients had to provide informed consent for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1C > 9%), testosterone deficiency (<3 ng/dl), treatment with PDE-5 inhibitors, and other erecting drugs during the first four weeks of the study and concomitant treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone and analogs, testosterone, antihypertensive, diuretic, antidepressant, sedative, neuroleptic, hypnotic and anti-epileptic drugs (within four months after study entry), and vitamin K antagonist (throughout the study) and corticosteroids (4 weeks before treatment). Furthermore, patients with concomitant neurological, hematologic, cardiovascular, coagulatory disease, and cancer were excluded, as well as patients who had undergone shock wave treatment within six months before study entry and patients who had undergone pelvic surgery, radical prostatectomy, and transurethral prostate resection within 4 weeks before baseline examination. All patients confirmed that they did not use any erecting drugs including PDE5 inhibitors during follow-up period of the study.

Based on own unpublished pilot data (expected mean IIEF-EF difference between ESWT- and placebo-treated patients = 4.9 ± 6.8) and a presumed dropout rate of 15%, we intended to include 66 patients. After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, national laws, and good clinical practice according to ISO 14 155:2011. The study was prospectively registered by the Turkish Ministry of Health (registration No. 71146310 [2014-MDD-CE-55]).

At the first study visit (V1), patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to ESWT or placebo treatment. Patients then underwent a 4-week washout period, followed by the baseline examination (V2) and a 4-week treatment phase. Follow-up examinations were at month 3 (V3), month 6 (V4), and month 12 (V5), whereby only treatment responders were evaluated at V4 and V5. Treatment responders of the ESWT and placebo group were defined as patients who gave at least two “yes” answers each to SEP2 and SEP3 (see below).

The treatment period consisted of 4 ESWT sessions (1× per week). During the 4-week treatment phase, ESWT was administered once a week using the DUOLITH ® SD1 shock wave generator, equipped with a focused shock wave handpiece with a long stand-off device (Storz Medical AG, Tägerwilen, Switzerland). Storz Medical Duolith is also a focused shock wave device. The penis was pulled manually, a total of 3000 shock wave pulses per session were delivered to ten positions throughout the penis shaft (dorsal left and right; 300 pulses per position) and crura bilaterally. Energy density and frequency were 0.20 mJ/mm2 and 5 Hz, respectively. The penetration depth was 15 ± 15 (0–30 mm) mm, and each treatment session lasted 10 minutes. No local or systemic analgesia was required due to the low energy density of ESWT. Placebo treatment was identical to ESWT, except that the stand-off device of the ESWT handpiece was filled with a shock wave absorbent material. All patients were blinded to their treatment allocation.

2.2 Study endpoints and assessments

Effectiveness was assessed by patient-reported outcomes measures, namely six questions on the erectile function (EF) of the IIEF questionnaire (IIEF-EF) to assess ED severity16 as well as two yes/no questions each of SEP17 and GAQ. The latter ones provide information on the ability for successful vaginal insertion (SEP2) and intercourse (SEP3) as well as on the improvement of erectile function (GAQ1) and the ability to engage in sexual activity by the treatment applied (GAQ2).

Primary endpoints were the improvement of IIEF by ESWT when compared to placebo at V3, with minimal clinically important differences according to baseline ED severity (mild: 2 points, moderate: 5 points, and severe: 7 points18 ) and the percentage of patients answering “yes” to SEP2 and SEP3 at V3. Secondary endpoints included descriptive data on IIEF-EF, SEP2, SEP3, GAQ1, and GAQ2, as well as demographic and clinical data of patients. Safety endpoints were medical device-related side effects such as swelling, reddening, hematoma, petechial, and pain, and other adverse events as defined by the patient.

2.3 Statistics

Statistical analyses (intent-to-treat population) were performed by using SPSS. Chi-square test and Welch's test were used to determine the categorical variables. Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were employed to compare data of ESWT- and placebo-treated patients at baseline and follow-up examinations. Missing values at V3, V4, and V5 were replaced by baseline levels (V2) according to the last observation carried forward (LOCF). p-values <0.05 were considered as being significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patients

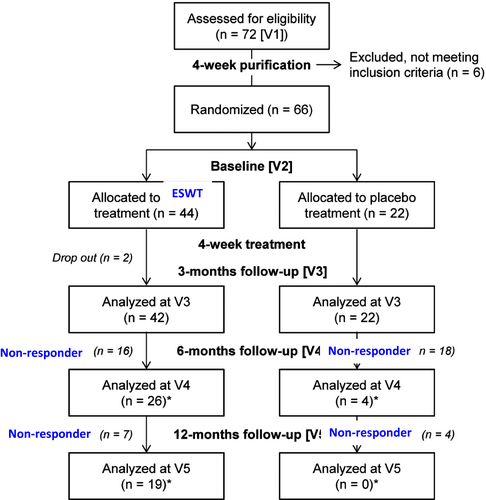

Out of 72 patients screened, 66 patients were enrolled and allocated to either ESWT (n = 44) or placebo treatment (n = 22). A total of 42, 26, and 19 patients in the ESWT group and 22, 4 and 0 patients in the placebo group completed the follow-up examinations at month 3 (V3), month 6 (V4), and month 12 (V5) respectively (Figure 1). At baseline (V2), no statistically significant differences could be found between the ESWT- and placebo-treated patients of the intention-to-treat population (n = 66) (Table 1). A total of 31 in the ESWT and 16 patients in the placebo group had at least one risk factor for ED including hypertension (5), diabetes mellitus (7), hypercholesterolemia (22), hypertriglyceridemia (11), hypothyroidism (1), and Peyronie disease (1). Testosterone levels were within the normal range, and all patients had mild erectile dysfunction at baseline, with IIEF-EF scores of 20.32 ± 2.32 (ESWT) and 19.68 ± 1.55 (placebo; p = 0.34).

| ESWT | Placebo | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 44 | 22 | |

| Age (years) | 42.32 ± 9.88 | 39.86 ± 11.64 | 0.374 |

| Height (cm) | 174.91 ± 6.27 | 175.50 ± 6.82 | 0.727 |

| Weight (kg) | 81.73 ± 11.00 | 80.91 ± 9.85 | 0.769 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.70 ± 3.29 | 26.30 ± 3.17 | 0.637 |

| ED duration (months) | 33.67 ± 36.46 | 37.19 ± 46.27 | 0.605 |

| IIEF-EF V1 | 20.36 ± 2.44 | 19.68 ± 1.55 | 0.321 |

| IIEF-EF V2 (baseline) | 20.32 ± 2.32 | 19.68 ± 1.55 | 0.340 |

| Testosterone (ng/dl) | 4.59 ± 1.47 | 4.40 ± 1.41 | 0.629 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.52 ± 0.70 | 5.53 ± 0.95 | 0.573 |

| Serum cholesterol (mg/dl) | 204.51 ± 44.67 | 180.81 ± 49.32 | 0.059 |

Note

- BMI = Body mass index; ED = erectile dysfunction; IIEF-EF = erectile function [EF] domain of the International Index of Erectile Function domain score; HbA1c = Glycosylated Hemoglobin, Type A1C; all values are presented as mean ± SD.

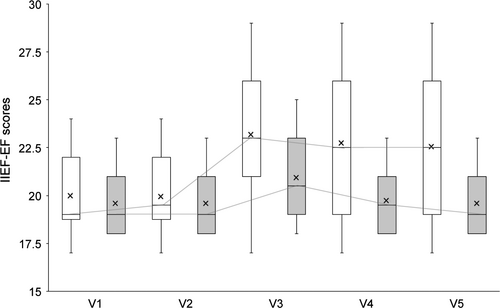

3.2 Endpoint measures

After treatment and 3-months of follow-up, the mean IIEF-EF score of ESWT-treated patients (23.10 ± 2.82) was significantly higher than that of placebo-treated patients (20.95 ± 2.19; p = 0.003). When compared with placebo, the mean IIEF-EF scores of ESWT-treated patients remained high during the follow-up of 6 months (22.67 ± 3.35 vs. 19.82 ± 1.56) [LOCF]; Figure 2).

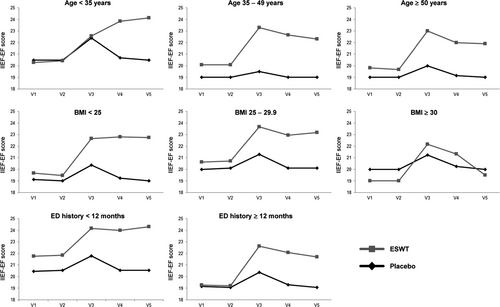

A minimal clinically important difference between the IIEF-EF scores at baseline examination (V2) and 3-month follow-up (V3) was observed in 74% of ESWT-treated patients and 36% of placebo patients. Furthermore, subgroup analyses suggested that the improvement of ED by ESWT detected at V3 was independent of age, BMI, and ED duration. However, at six month follow-up (V4), the beneficial effect of ESWT seemed to decline in patients with a BMI ≥ 30, in patients older than 35 years, and in patients with ED history ≥12 months (Figure 3).

In a combined analysis of SEP2 and SEP3 at V3, ESWT significantly improved ED in terms of successful penetration and sexual intercourse. The percentage of patients who stated that they had been able to penetrate and to have successful intercourse in ≥50% of four attempts during the last four weeks (at least two “yes” answers to each SEP2 and SEP3 question) was significantly higher in ESWT-treated patients (31.82%) than in placebo patients (0%; p = 0.001). When asked about successful penetration or sexual intercourse separately, however, differences were significant for SEP3 (p = 0.001) but not for SEP2 (p = 0.839). Table 2 shows the yes/no ratio of questions concerning the success of four sexual intercourse attempts in the 4 weeks preceding the V3 examination (SEP2, SEP3, GAQ-1, and GAQ-2).

| ESWT | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|

| SEP2 | 0.77 ± 0.42 | 0.70 ± 0.42 |

| SEP3 | 0.34 ± 0.47 | 0.01 ± 0.05 |

| GAQ−1 | 0.57 ± 0.49 | 0.18 ± 0.39 |

| GAQ−2 | 0.33 ± 0.44 | 0.05 ± 0.21 |

Note

- SEP 2,3 = Sexual Encounter Profile diary, question 2 (“Were you able to insert your penis into your partner's vagina?”) and question 3 (“Did your erection last long enough for you to have successful intercourse?”); GAQ 1, 2 = Global Assessment Questions, question 1 (“Over the past four weeks has the treatment you have been taking improved your erectile function?”) and question 2 (“If yes, has the treatment improved your ability to engage in sexual activity over the past four weeks?”). Values are mean results ±SD.

3.3 Safety

One safety event (pain) and headache (1) occurred in the placebo group. A total of 12 adverse events were reported by ESWT patients (n = 10) included headache (2), fatigue and nausea (1), nausea and headache (1), dysuria (1), fatigue and tiredness (2), headache and fatigue (1), and mild fever (1). After the treatment phase, the headache was the most frequently reported adverse (1 placebo, 4 ESWT patients). No adverse event occurring at the sites of treatment was reported.

4 DISCUSSION

In this prospective randomized placebo-controlled single-blinded trial, 4-week ESWT significantly improved erectile function of patients with vasculogenic mild ED in a follow-up of 3 to 6 months. Almost two-thirds of ESWT-treated patients showed a minimal clinically important increase in IIEF-EF scores (ESWT 74% vs. placebo 36%), and only ESWT-treated patients reported successful penetration and intercourse in at least half of attempts during the 4 weeks preceding the 3-month follow-up (placebo 0%). The success of the placebo in the treatment of ED may exceed 30%; this rate may be increased in patients with mild ED.19 Carvalho de Araujo et al. assessed the effect of placebo on 123 patients with ED. They showed that the ED severity was improved in 36.7% of patients who awake to be using a placebo.20 Therefore, when compared to placebo, ESWT significantly improved erectile function, intercourse, and overall satisfaction (IIEF-EF) as well as erection duration (SEP3) in the long term. However, effects on erection hardness (SEP2) did not significantly differ between both study groups. Since only rare and mild side effects occurred, without any obvious relation to treatment, ESWT can be considered as being feasible and safe for patients with vasculogenic ED.

In this respect, our results nicely correspond with those of recent studies of similar designs, that is, prospective placebo-controlled studies including a PDE-5 inhibitor washout phase,9, 10 and also corresponds to the results of both studies, in which patients continuously received PD-5 inhibitors throughout the study period,14, 21 and pilot studies without placebo control.13, 21, 22 Other studies also demonstrated an ESWT-mediated improvement of erectile function by patient-reported outcomes other than IIEF-EF, but found no statistically significant difference in IIEF-EF scores between study groups.23, 24 Increases in SEP3 and combined SEP2/SEP3 analyses that occurred in our study correspond to the results of Bechara et al.21 and Ruffo et al.22 In our study, however, the effects on both SEP2 and SEP3 were less pronounced than those reported by these articles.

The proposed mechanisms of action of ESWT result in several biological reactions in target tissues. One of these reactions is the release of angiogenic factors (VEGF) triggering neovascularization and vasculogenesis, which improves the blood supply and microcirculation25, 26 and enhances macrophage activity as well as tissue repair.27 At first, animal ED models demonstrated that ESWT could positively affect pathological changes of the corpus cavernosum, endothelial dysfunction, and peripheral neuropathy.28-30 In ED patients, Vardi et al.9, 11 then demonstrated that increased IIEF-EF scores after ESWT strongly correlate with an objective improvement of penile hemodynamics. During the past few years, an increasing number of clinical trials have therefore been evaluating the effects of ESWT on ED, and three meta-analyses on 21 studies including more than 600 to 800 ED patients, respectively, demonstrated a significant and clinically relevant improvement of erectile function by ESWT, when compared to placebo.31-33 Due to the low-intensity shock wave energy applied in ED studies, almost no side effects have been reported.9, 10, 13, 21-23 In our study, there were no serious adverse effects noted during treatment sessions, and adverse effects were similar to previous studies.34 Therefore, ESWT can be considered as being effective, safe, and tolerable in the treatment of ED.

Despite these encouraging results, further research is needed to define subgroups of ED patients that would benefit most from ESWT therapy and to establish optimal treatment protocols that are tailored to these subgroups. Patients with mild to moderate ED have been shown to profit more from ESWT than patients with severe ED.31 In addition, comorbidities seem to affect the outcome, and younger patients without comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes are more likely to have beneficial outcomes.35 Preliminary subgroup analyses of our data actually suggested that patient characteristics such as higher age, higher BMI, and longer ED history might negatively impact on ESWT outcomes in the long term. However, the number of patients in the subgroups is too low for statistical analysis.

Likewise, there are no generally applied treatment protocols, although studies have suggested that ESWT treatment success is related to energy flux density, the number of ESWT pulses per treatment, treatment duration and frequency, and location of treatment.31 In our study, we applied an energy flux of 0.20 mJ/mm2, which lies within the range of most ESWT studies31 and was demonstrated to improve angiogenesis in human ischemic tissues, objectively.36 Regarding the number of shock wave pulses per treatment, most studies applied 1500 to 5000 pulses, but the best results have been found with 3000 pulses,31 as applied in our study. It is presently unclear how treatment duration and frequency influence outcomes. More frequent and longer treatment does not improve the outcome substantially,31 but more research is needed. Finally, the optimal position on the penis for ESWT treatment needs further elucidation. In our study, we applied ESWT on ten different positions on the penis shaft (range in published studies 3–6), because studies have suggested that more positions might result in better outcomes.31 Meanwhile, it is becoming a common approach not to treat the penis only, but also the crura. Furthermore, Storz Medical Duolith is a focused shockwave device. The F-SW handpiece was used with the long stand-off II in order to reduce the focal depth from 50 mm down to 15 mm. The focal length is approximately 30 mm, so that from the treatment pint of the tissue layer from 0 to 30 mm has been treated.

There are very limited well-designed studies on whether this machine (DUOLITH ® SD1) is effective for patients with ED. A randomized controlled study that included 112 patients with organic ED who underwent treatment with either sham or ESWT was published by Olsen et al. with the same machine. They reported that the IIEF-EF domain did not significantly improve in the treatment group compared with the control group. However, they did not divide patients according to ED severity; hence, there was not known effect of ESWT on patients with mild, moderate, and severe ED separately. However, our study has focused on patients with mild ED and the result of the study showed that this machine is effective for patients with mild ED.

The study included people aged between 18 and 75 years old and the mean age of the treatment and placebo groups were 42 and 40 years old, respectively. The age of those patients seems to be quite young for ED. However, several patients included in the study had at least one risk factor for ED. The prevalence of ED was reported between 2% and 40% in people younger than 40 years old and also nearly one out of four men with new-onset ED are younger than 40 years old.37 According to current literature, ED can be a marker of silent cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, particularly in young patients. Despite the fact, young patients with erectile dysfunction are likely diagnosed as psychogenic ED, the rate of vasculogenic ED has been reported between 32% and 72% in patients younger than 40 years old.38

Our study has three limitations to be considered. First, the study was single-blinded, which might introduce a potential for investigator bias, even when the most database on patient-reported outcomes. Second, the number of patients was relatively small, resulting in the lack of placebo controls at long-term follow-up. LOCF is a common approach for handling the problem of missing data during long-term follow-up but may result in biased estimates. While our results are though promising, a number of factors pertaining to ESWT (technical parameters and patient characteristics) as well as safety issues such as long-term histological changes have yet to be fully elucidated, and future large-scale studies are needed to provide solid evidence for ESWT efficacy and safety in ED patients. Third, we only included responders in the open-label extension study (V4, V5), which might have led to underreporting of adverse events.

5 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study confirmed the efficacy and safety of ESWT in relatively young patients with mild ED. The beneficial response, that is, the increase of IIEF-EF scores in ESWT-treated patients, was maintained during the 6-month follow-up. Additionally, ESWT was demonstrated to be feasible and easy to administer. Further research and large-scale randomized trials are now warranted to define subgroups of ED patients benefiting most from ESWT and to establish corresponding treatment protocols.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by STORZ Medical, Turkey. STORZ Medical has offered the device and the probes for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

Conception and design: Abdulkadir Özmez, Mazhar Ortac, and Ateş Kadıoglu. Acquisition of data: Mazhar Ortac and Abdulkadir Özmez. Analysis and interpretation of data: Mazhar Ortac, Abdulkadir Özmez, Nusret Can Cilesiz, and Erhan Demirelli Ateş Kadıoglu. Drafting the article: Mazhar Ortac, Nusret Can Cilesiz, and Erhan Demirelli. Revising it for intellectual content: Ateş Kadıoglu. Final approval of the completed article: Abdulkadir Özmez, Mazhar Ortac, Nusret Can Cilesiz, and Erhan Demirelli Ateş Kadıoglu.