A review of behavioral alcohol interventions for transplant candidates and recipients with alcohol-related liver disease

Abstract

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is a common indication for liver transplantation. Reflecting growing consensus that early transplant (ie, prior to sustained abstinence) can be a viable option for acute alcoholic hepatitis, access to liver transplantation for ALD patients has increased. Prevention of alcohol relapse is critical to pretransplant stabilization and posttransplant survival. Behavioral interventions are a fundamental component of alcohol use disorder treatment, but have rarely been studied in the transplant context. This scoping review summarizes published reports of behavioral and psychosocial alcohol interventions conducted with ALD patients who were liver transplant candidates and/or recipients. A structured review identified 11 eligible reports (3 original research studies, 8 descriptive papers). Intervention characteristics and clinical outcomes were summarized. Interventions varied significantly in orientation, content, delivery format, and timing/duration. Observational findings illustrate the importance of situating alcohol interventions within a multidisciplinary treatment context, and suggest the potential efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and motivational enhancement interventions. However, given extremely limited research evaluating behavioral alcohol interventions among ALD patients, the efficacy of behavioral interventions for pre- and posttransplant alcohol relapse remains to be established.

Abbreviations

-

- AAU

-

- alcohol addiction treatment unit

-

- ALD

-

- alcohol-related liver disease

-

- AUD

-

- alcohol use disorder

-

- CDT

-

- carbohydrate-deficient transferrin

-

- CBT

-

- cognitive-behavioral therapy

-

- EtG

-

- ethyl glucuronide

-

- MET

-

- motivational enhancement therapy

-

- RP

-

- relapse prevention

-

- TAU

-

- treatment as usual

1 INTRODUCTION

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), including alcoholic cirrhosis and acute alcoholic hepatitis, represents the majority of liver disease cases1, 2 and is a primary indication for liver transplant.3 Despite evidence for positive transplant outcomes,4-6 ALD patients have historically faced considerable barriers to transplant access, including the common prerequisite of 6 months of continuous abstinence prior to transplant listing.7-9 More recently, developments such as growing consensus that early transplant (ie, prior to sustained abstinence) is a viable option for acute alcoholic hepatitis,3, 6, 10 and improvements in the treatment of hepatitis C infection, have contributed to increased transplant access for ALD patients.11

Because posttransplant resumption of alcohol use can compromise long-term survival,12-14 comprehensive alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment is a crucial element of pre- and posttransplantation procedures.15, 16 While select pharmacotherapies (eg, acamprosate, baclofen) may be safely prescribed to ALD patients to help maintain abstinence,17 the extent to which behavioral alcohol interventions (a critical element of evidence-based alcohol treatment approaches) are effective for ALD patients is uncertain. ALD patients represent a unique subpopulation of those with AUD, often presenting with a chronic and severe history of alcohol addiction and variable insight and motivation into alcohol problems.18, 19 These considerations may call into question the generalizability of conventional AUD interventions to ALD patients.19

Randomized, prospective research on behavioral alcohol interventions in the transplant context is scant, leaving providers to make decisions about AUD treatments without ample research evidence. Nonetheless, several teams internationally have reported information on behavioral interventions for ALD patients, including some novel innovations.20 Given that there have been few efforts to summarize this literature, this scoping review aims to summarize characteristics and clinical outcomes of behavioral alcohol interventions for ALD patients in the transplant context. Reviews of AUD treatment in ALD more broadly, including pharmacological treatment approaches, are available elsewhere.18, 17

2 METHODS

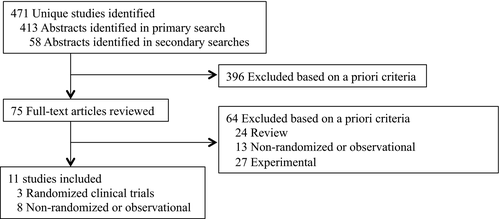

We identified original publications reporting on behavioral alcohol interventions in the ALD transplant context through October 2018, using structured keyword searches in PubMed (“liver transplant*” AND “alcoholic liver disease”) AND (“intervention” OR “relapse prevention” OR “treatment” OR “counseling” OR “therapy” OR “transplant list” OR “wait list”). Eligible reports were required to provide information on behavioral AUD interventions delivered to ALD transplant candidates or recipients, and to present data addressing potential efficacy of the intervention. We considered any nonpharmacological interventions, regardless of modality, delivery format, research design, or degree of empirical support. Case reports and non-English publications were excluded. After reviewing abstracts, potentially eligible articles were retrieved. Secondary searches involved reviewing reference lists and citations of eligible studies and relevant review articles. Studies were reviewed to determine whether they included information about psychosocial or behavioral treatments; if so, descriptive data were extracted.

3 RESULTS

Search procedures (Figure 1) yielded 471 unique abstracts (1986-2018), 75 full-text articles screened, and 11 eligible reports from 10 unique research teams. Reports included 2 completed20, 21 and 1 failed19 randomized trial, and 8 observational studies (3 prospective and 5 retrospective).22-29 Refer to Table 1 for study characteristics. The treatments identified were diverse in modality, theoretical orientation, and timing/duration, ranging in intensity from multicomponent prospective interventions to a 1-time abstinence contract. Most observational studies involved comparisons to retrospective control groups, and no intervention was studied more than once. Only 1 team reported implementing a specified, empirically supported behavioral intervention.19

| Study, location, and design | Transplant context | Sample characteristics (M) | Intervention setting | Intervention modality and format | Intervention duration | Longest follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Addolorato et al. (2013) Italy Nonrandomized, retrospective |

I: pre- and post-LT Follow-up: post-LT |

I: 50.34 y of age, 89% male, N = 55 | Outpatient, integrated, single center | Alcohol addiction treatment Individual Pharmacotherapy: baclofen |

Pre-LT: weekly for 1st mo, biweekly for 2nd and 3rd mo, monthly thereafter Post-LT: variable |

108 mo |

| C: 47.97 y of age, 89% male, N = 37 | Outpatient, nonintegrated, single center | NR | Monthly | 180 mo | ||

Attilia et al. (2018) Italy Nonrandomized, I: prospective, C: retrospective |

I: pre- and post-LT Follow-up: post-LT |

I: 56 y of age, 87% male, N = 69 | Outpatient, integrated, single center |

Multidisciplinary support Individual, with caregiver |

Pre- and post-LT: 6 monthly sessions, as needed thereafter | 60 mo |

| C: 53 y of age, 78% male, N = 18 | NR | NR | 106 mo | |||

|

Bjornsson et al. (2005) Sweden Nonrandomized, retrospective |

I: pre-LT Follow-up: post-LT |

53 y of age, 79% male I: N = 63 C: N = 40 |

Outpatient, nonintegrated, single center | Structured management. Format NR | Interviews at 0.25, 1, 3, 5 y post-LT | 60 mo |

| NR | ||||||

|

DeMartini et al. (2018). USA Randomized, prospective |

I and follow-up: pre-LT | I: 49.88 y of age, 75% male, N = 8 | Outpatient, nonintegrated, single center | RP text messages Individual | 3×/d for wk 1-4, 3×/wk for wk 5-8 | None |

| C: 51.86 y of age, 72% male, N = 7 | Individual | Variable | ||||

|

Erim et al. (2016) Germany Nonrandomized. Prospective |

I and follow-up: pre-LT | I: 53.1 y of age, 54.8% male, N = 42 | Outpatient, integrated, single center |

Eclectic Group |

Attended ≥ 9 of 12 sessions over 6 mo | 6 mo |

| C: 52.6 y of age, 65.5% male, N = 58 | Attended < 9 of 12 sessions over 6 mo | |||||

|

Georgiou et al. (2003) United Kingdom Nonrandomized, prospective |

I: pre-LT Follow-up: post-LT | 48.95 y of age, N = 20 | Outpatient, integrated, single center | Social behavior and network therapy Individual, with support person |

3 sessions, 2-4 wks between sessions | 6 mo |

Kollman et al. (2016) Austria Nonrandomized, retrospective |

78.5% male, N = 382 | Outpatient, assessment integrated, treatment nonintegrated, single center | Structured interviewing, including CBT elements Individual |

1 interview pre-LT. Post-LT: weekly for 1st mo, biweekly for 2-3 mo, biannually for 2 y, then annually | Median = 73 mo | |

|

Masson et al. (2014) United Kingdom Nonrandomized, retrospective |

I: pre-LT, Follow-up: post-LT | I: 55 y of age, 68% male, N = 44 | Outpatient, integrated, single center |

Lifetime abstinence contract Format: NA |

NA | Median = 39 mo |

| C: 54 y of age, 70% male, N = 96 | None | Median = 120 mo | ||||

Rodrigue et al. (2013) USA Nonrandomized, retrospective |

I: pre- and/or post-LT Follow-up: post-LT |

55 y of age, 86% male, N = 118 | Outpatient, nonintegrated, single center | Community-based addiction treatment Variable format | Number of sessions and duration varied. Included pre- only, post- only, pre and post, and no treatment groups | M = 55 mo |

Weinrieb et al. (2001) USA Randomized, prospective Failed study |

I and follow-up: post-LT | Screened patients: 47 y of age, 90.9% male, N = 55 N = 5 randomized |

Outpatient, nonintegrated, single center | MET and case management. Individual Pharmacotherapy: naltrexone or placebo |

4 sessions over 6 mo | All patients withdrew prior to completing the intervention |

Weinrieb et al. (2011) USA Randomized Prospective |

I: pre-LT Follow-up: pre- and post-LT |

I: 50.5 y median age, 85% male, N = 46 | Outpatient, integrated, 2 centers | MET and case management Individual |

7 sessions over 6 mo | 24 mo after randomization |

| C: 48.0 y median age, 82% male, N = 45 | NR | NR |

- C, control; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; I, intervention; LT, liver transplant; M, mean; MET, motivational enhancement therapy; mo, month; NA, not applicable, NR, not reported; RP, relapse prevention; wk, week; y, year.

3.1 Randomized controlled trial

DeMartini et al20 reported the first test of a technology-based relapse prevention intervention. Researchers randomly assigned 15 transplant candidates to receive an 8-week text messaging intervention in addition to psychological addiction counseling, or psychological addiction counseling alone. Text messages addressed craving, triggers, high-risk situations, mood, health, and coping strategies, and elicited responses from participants. Alcohol use was assessed at baseline and at 8 weeks with self-report and urine ethyl glucuronide (EtG). At baseline, 2 (25%) intervention and 3 (43%) control participants had positive EtG tests. At week 8, 0 intervention and 2 (33%) control participants had positive tests. Intervention feasibility/engagement data from 6 (75%) intervention participants showed that most reported good engagement (eg, reading/responding to all study text messages), and high intervention acceptance/satisfaction (eg, considered the frequency of messages appropriate). Participants also reported the text messages as helpful with abstinence, coping with craving, and stress.

A failed randomized controlled trial19 aimed to randomize 60 posttransplant ALD patients to receive placebo or naltrexone, in addition to structured motivational enhancement therapy (MET) and case management. Fifty of 55 potential participants were unable/unwilling to participate. Five participants were randomized; all reported abstinence during the first year posttransplant. All participants withdrew due to time constraints, substantial demands of post-orthotopic liver transplantation medical management, and/or fear of hepatotoxicity due to medications. The study was terminated due to recruitment challenges. In a follow-up study,21 the same researchers assigned 91 pretransplant candidates to structured MET30 and case management, or treatment as usual (TAU; referrals to community outpatient alcohol treatment). Thirty-five (76%) MET and 34 (76%) TAU participants completed the intervention. Thirteen (28%) MET and 12 (27%) TAU participants completed 72 follow-up weeks. Alcohol use was assessed throughout the intervention and follow-up using self-report and breath-alcohol testing. Two (4%) MET and 3 (7%) TAU participants reported alcohol use in the 30 days before randomization. Pretransplantation, 12 (26%) MET and 11 (24%) TAU participants consumed alcohol. Twenty-nine participants (32%) underwent transplantation within 48 weeks of randomization. Of these, 16 died (MET: n = 9; TAU: n = 7). Data on graft survival were not reported. Data on posttransplant drinking were available for only 8 MET and 9 TAU participants. Of these, MET participants reported significantly fewer drinks/drinking day (median = 3.75) and drinking days (median = 2 days over 60 weeks of follow-up) than TAU participants (median = 4.3 drinks/drinking day; median = 7 days over 96 weeks of follow-up).

3.2 Nonrandomized prospective studies

Attilia et al23 enrolled 69 participants in a multidisciplinary support program to promote abstinence. Pre-and posttransplant behavioral alcohol treatment was provided by physicians and psychologists with expertise in addiction and hepatology. Alcohol use was assessed by self-report, collateral informant, carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) tests, and blood alcohol tests. If posttransplant alcohol use was detected, participants took part in a 2-week intensive day treatment program (treatment approach unspecified), followed by weekly sessions. Participants were abstinent for ≥6 months prior to study enrollment when possible. Alcohol relapses (defined as ≥5 units/d for >2 consecutive days or ≥14 units/wk for ≥4 weeks) and lapses (any other consumption) were assessed over 5 years of follow-up. Outcomes were compared with chart review data from ALD patients (n = 18) who underwent transplantation prior to the multidisciplinary program. Six (8.7%) intervention and 6 (33.3%) historical patients relapsed. Additionally, 14 (20.3%) of intervention participants had 1 lapse. Fewer months of pretransplant multidisciplinary support was a risk factor for posttransplant relapse. However, mortality over follow-up (including 19% of intervention participants) did not differ by group or relapse status.

Erim et al25 prospectively enrolled 100 transplant candidates in a standardized group behavioral intervention, developed and evaluated by the same research group.31, 32 The intervention was eclectic, including motivational interviewing, psychoeducation, situational analysis, abstinence contracting, progressive muscle relaxation, and problem solving. Alcohol use was assessed with urinary EtG, and compared between participants who attended ≥9 (completers) vs <9 sessions (dropouts). At baseline, 20 (47.6%) completers and 27 (46.6%) dropouts were abstinent for >6 months. Alcohol relapse was confirmed significantly less frequently for completers (14.2%) than for dropouts (24.0%). No deaths were reported.

Georgiou et al26 prospectively enrolled 20 transplant candidates with 6+ months’ abstinence (M = 29.7 months, range = 6-96) to a “motivational-style” social behavior and network therapy.33 Content focused on psychoeducation and relationships, social support, pleasant activities, and relapse prevention (RP). No control condition was included. One participant died during data collection; 89% of remaining participants completed all sessions. Alcohol use was assessed over 6 months posttransplant using self-report and blood-alcohol tests; 42% of participants consumed alcohol, 21% consumed weekly, and 5% drank >20 units weekly.

3.3 Retrospective studies

One study24 compared posttransplant alcohol use before versus after the implementation of a structured management intervention for alcohol at a transplant center. Structured management was led by an addiction psychiatrist and a transplant social worker. Participation required ≥6 months (range: 6-15 months) of pretransplant abstinence. All patients signed abstinence contracts, and most participated in 12-step groups. In total, 30% of a historical control and 58% of the multidisciplinary support group attended posttransplant AUD treatment. Thirteen (22%) multidisciplinary support and 19 (48%) historical patients resumed drinking over 5 years posttransplant (assessed with self-report, collateral informant, and clinical judgment). One- and 5-year survival rates were, respectively, 83% and 78% in multidisciplinary support patients, and 92% and 90% in historical patients.

Addolorato et al22 used retrospective chart reviews to compare posttransplant outcomes before versus after integrating an alcohol addiction treatment unit (AAU) within the transplant center. Most patients had attained ≥6-month abstinence pretransplant. A historical group received posttransplant psychological support from consulting addiction psychiatrists; the AAU group received treatment from providers (internists, physicians-in-training, and psychologists with expertise in AUD, hepatology, and neuroscience) integrated in the transplant team. Nine patients received treatment with baclofen and 24 attended community addiction support groups. Abstinence/lapse was assessed using self-report, collateral informant, biomarkers, breath-alcohol concentration, and CDT, and relapse was defined as >4 drinks/d or ≥14 drinks/wk. Posttransplant alcohol use was assessed over 9 and 15 years for the AAU and historical group, respectively. Rates of alcohol resumption and death were significantly lower in the AAU versus historical group. Abstinence rates were 83.9% in the AAU and 64.9% in the historical group. Eight (14.5%) AAU and 14 (37.8%) historical patients died during follow-up.

Another team29 reviewed medical records of 118 transplant recipients (with ≥3 months of pretransplant abstinence) to examine pre- and/or posttransplant community-based addiction treatment attendance in relation to posttransplant alcohol relapse. Patients were classified as receiving low-/moderate-/high-intensity alcohol treatment, based on participation patterns and number/types of treatment attended. Fifty-four patients received no treatment, 29 received pretransplant treatment only, 3 received posttransplant treatment only, and 32 received pre- and posttransplant treatment. Relapse (assessed via self-report, collateral informant, and laboratory tests) was defined as any use; relapse severity was characterized as low/moderate/high. Sixty-two (54%) patients attended pretransplant treatment: 23 (38%) attended at low intensity, 35 (57%) at moderate intensity, and 4 (5%) at high intensity. Posttransplant relapse incidence did not differ significantly across low-(30%), moderate-(26%), or high-(67%)intensity treatment groups, nor did extent of relapse differ. Two participants lost grafts following relapse. Thirty-five (30%) patients attended posttransplant treatment, and posttransplant relapse was significantly lower for attendees (14%) versus nonattendees (42%). Those receiving both pre-and posttransplant treatment had lower relapse incidence (16%) than those receiving pretransplant-only (45%) or no treatment (41%). Among those who relapsed, mortality rates did not vary across no-treatment (n = 5), pretransplant treatment (n = 2), or pre- and posttransplant treatment (n = 1) groups. None of 3 patients receiving posttransplant treatment relapsed.

Another study28 involved chart reviews to compare posttransplant alcohol use before versus after the implementation of a lifetime abstinence contract. At transplantation, patients were alcohol abstinent for 12-26 months. Posttransplant drinking was assessed with self-report and blood alcohol tests, and operationalized as harmful (>168 g/wk or with evidence of physical harm), modest (<168 g/wk), or occasional (less than weekly) use. Abstinence rates did not differ for abstinence contract (66%) or historical (61%) patients. Occasional (abstinence contract: 5%; historical: 15%), moderate (abstinence contract: 18%; historical: 8%), and harmful (abstinence contract: 11%; historical: 16%) drinking did not differ between patients. Mortality rates were greater in the historical (40%) than in the abstinence contract group (7%). Mortality did not differ among those who relapsed (31%) versus abstained (28%).

Kollman et al27 used chart review to examine posttransplant alcohol use in 382 transplant recipients who received pretransplant structured interviewing, including elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). A transplant psychologist conducted structured interviews, which assessed causes of alcohol consumption, coping mechanisms, abstinence, and future goals. If drinking was suspected, patients attended specialized treatment (unspecified). Any posttransplant alcohol consumption (assessed with self-report and CDT) was considered a relapse. Relapse rates were 3.9% at 1 year, 10.4% at 3 years, 13.9% at 5 years, and 16.2% overall. One- and 5-year survival rates were 82% and 67%, respectively. One- and 5-year graft survival rates were 80% and 67%, respectively. Alcohol relapse was not related to mortality.

4 DISCUSSION

This review aimed to identify and summarize published reports of behavioral or psychosocial interventions provided to ALD patients in the transplant context. Overall, this review highlights the shortfall of systematic research on behavioral alcohol treatments in this context, and the lack of randomized trials in particular. These considerations, along with minimal information for most of the behavioral interventions described, precluded a systematic review of this literature. The shortage of research in this area likely reflects several challenges inherent to studying this population, which include significant medical complications and psychiatric comorbidities in ALD patients, and challenges in engaging patients in alcohol treatment (perhaps reflecting variable insight and motivation).19 Consequently, the present research base precludes evidence-based guidelines for behavioral RP treatments in the transplant context, a notable limitation given trends toward increasing transplant access.6, 34

Despite the lack of randomized, prospective intervention research, descriptive results provide clues about the feasibility and utility of behavioral alcohol interventions for ALD patients. Descriptive evidence suggests that multicomponent interventions incorporating CBT principles could prove efficacious.22, 23 For example, RP focuses on coping skills acquisition, identifying high-risk situations, and tailored RP plans.35, 36 Notably, there remain no controlled trials of RP for ALD patients. However, DeMartini et al20 found initial evidence for the feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of a novel text-messaging intervention informed by RP.

MET, an evidence-based approach,37 represents another candidate intervention. Again, however, efficacy for ALD patients is not established.19, 21 Of note, ALD patient-specific characteristics may influence the relevance of MET across pre- and posttransplantation contexts. In the pretransplant evaluation period, ALD patients typically report absolute commitment to abstinence from alcohol because this is often a strict requirement for being placed on the waitlist. Because MET relies on building motivation by resolving ambivalence, patients who are highly motivated and resolute in behavior change goals might be better suited for skills-based interventions (eg, RP). For candidates low in insight/readiness, or patients who have lapsed, MET may be indicated.19, 38

Several groups reported using abstinence contracting, which is common to most transplant clinics,39 in conjunction with other interventions.24-26, 29 However, 1 study examining contracting was not supportive,28 and evidence that abstinence contracting facilitates abstinence is absent.

Notably, interventions varied with respect to the degree of integration within the transplant team/program. Emerging evidence and clinical consensus suggests that, when possible, integration of addiction treatment within the transplant setting is ideal.22, 23 One study involving a pre/post design found that the addition of integrated treatment was associated with more favorable outcomes.22 Integrated interventions can facilitate access to evidence-based addiction treatments, and might improve staff openness to providing transplant to ALD patients.22 Integrating distance alcohol interventions (eg, text messaging or telemedicine) into transplant programs may also help to mitigate logistical or health access barriers to alcohol treatment.

Evidence about the ideal timing, treatment components, and duration of behavioral alcohol interventions is also lacking. Some findings indicated a positive association between intervention length and drinking outcomes.23, 25 However, because no studies manipulated treatment intensity/duration, these differences could reflect participant characteristics (eg, motivation) associated with treatment persistence, rather than treatment intensity/exposure. Nonetheless, it is assumed that access to both pre- and posttransplant alcohol interventions could improve abstinence rates.29 While posttransplant psychosocial treatments may be difficult to deliver reliably due to medical 19 and distance factors, some groups have successfully done so,22, 23, 29 and there is consensus about the importance of posttransplant interventions and monitoring.

A limitation of this review is the focus on published studies, which themselves often provided limited information on intervention methods. Additional behavioral interventions have likely been incorporated in clinical settings, so this review might underestimate the range of interventions in use. Importantly, the small, predominantly observational body of available research (often without control groups) precluded inferences about intervention efficacy. Further randomized trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of established AUD interventions,21 and adaptations22 for ALD patients, and to test independent and combined efficacy of behavioral and pharmacological alcohol interventions. In addition, examining the extent to which ALD-specific relapse risk factors (eg, concurrent polysubstance use, motivation, low social stability)9 impact responses to alcohol interventions is an important priority. Rather than implementing established interventions “out of the box,” developing modified interventions that account for unique complexities of the ALD population and transplant context is likely imperative.22

Future work should test interventions in both pre- and posttransplantation contexts, with dimensional assessments of alcohol use and clear operationalization of lapse and relapse. Work in this area should also attend to evolving conceptual and measurement issues pertaining to alcohol relapse40, 41 and alcohol reduction endpoints42 in the context of AUD treatment research with ALD patients. Finally, linking the efficacy of these interventions to longer-term outcomes is critical, given the association of relapse severity and mortality among transplant recipients.13, 14

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Descriptive data supporting the conclusions are available in Table 1.