Everolimus Versus Mycophenolate Mofetil De Novo After Lung Transplantation: A Prospective, Randomized, Open-Label Trial

Abstract

The role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors in de novo immunosuppression after lung transplantation is not well defined. We compared Everolimus versus mycophenolate mofetil in an investigator-initiated single-center trial in Hannover, Germany. A total of 190 patients were randomly assigned 1:1 on day 28 posttransplantation to mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or Everolimus combined with cyclosporine A (CsA) and steroids. Patients were followed up for 2 years. The primary endpoint was freedom from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS). The secondary endpoints were incidence of acute rejections, infections, treatment failure and kidney function. BOS-free survival in intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was similar in both groups (p = 0.174). The study protocol was completed by 51% of enrolled patients. The per-protocol analysis shows incidence of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS): 1/43 in the Everolimus group and 8/54 in the MMF group (p = 0.041). Less biopsy-proven acute rejection (AR) (p = 0.005), cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigenemia (p = 0.005) and lower respiratory tract infection (p = 0.003) and no leucopenia were seen in the Everolimus group. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreased in both groups about 50% within 6 months. Due to a high withdrawal rate, the study was underpowered to prove a difference in BOS-free survival. The dropout rate was more pronounced in the Everolimus group. Secondary endpoints indicate potential advantages of Everolimus-based protocols but also a potentially higher rate of drug-related serious adverse events.

Abbreviations

-

- AR

-

- acute rejection

-

- BOS

-

- bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome

-

- CF

-

- cystic fibrosis

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- CMV

-

- cytomegalovirus

-

- COPD

-

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

- CsA

-

- cyclosporine A

-

- DLTx

-

- double-long transplantation

-

- GFR

-

- glomerular filtration rate

-

- HUS

-

- hemolytic–uremic syndrome

-

- ICU

-

- intensive care unit

-

- IPF

-

- idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

-

- ITT

-

- intention to treat

-

- LTx

-

- lung transplantation

-

- MMF

-

- mycophenolate mofetil

-

- mTOR

-

- mammalian target of rapamycin

-

- Re-LTx

-

- recurrent lung transplantation

-

- SLTx

-

- single-lung transplantation

-

- TMA

-

- thrombotic microangiopathy

Introduction

As an established treatment for end-stage lung diseases, lung transplantation has approached a 1-year survival rate of above 80% 1. Therefore, pretransplant morbidity and chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) 2 have become the major limiting factors for long-term graft and patient survival. Along with viral infection and ischemic injury, acute rejection has been found to be a major risk factor for the development of CLAD 3. Thus, efforts have been made to improve immunosuppressive therapy so that the incidence and severity of both viral infections and acute rejections are minimized. Moreover, immunosuppressive protocols after lung transplantation seem to be more aggressive than after any other solid organ transplantations. Therefore, high exposure to immunosuppressive drugs and the effects of comedication lead to a high incidence of adverse events 4 and toxicity.

Everolimus is a proliferation signal inhibitor and has demonstrated in vitro and, in preclinical models of acute rejection, enhanced immunosuppressive potential 5. Everolimus has been used for triple immunosuppressive therapy following kidney transplantation as an alternative to cell cycle inhibitors such as azathioprine, showing less acute rejection and fewer cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections 6, 7. When used in heart transplant recipients, a trend of fewer acute rejections and a definitive advantage in avoidance of allograft vasculopathy were reported 7.

For lung transplant recipients, the efficacy of Everolimus was compared to azathioprine in maintenance immunosuppression in a multicenter prospective trial: No difference was seen in the rates of graft loss and death at 24 months follow-up. Also, a higher incidence of kidney failure was reported 8. In addition, a study by Bhorade et al compating azathioprine to sirolimus, another mTOR inhibitor, failed to demonstrate less rejections in the sirolimus arm 9.

The open question of possible advantages of Everolimus in lung transplantation encouraged us to perform a prospective clinical trial. Unlike in multicenter studies, avoiding the diversity of lung transplant protocols, a study at a high-activity single center could be beneficial. In addition, Everolimus was compared to the more contemporary cell cycle inhibitor mycophenolate mofetil. It was administered not as a fixed dose but in a trough level–based regimen and was administered relatively early after lung transplantation.

Methods

Trial design

A prospective, randomized, single-center trial was performed over a period of 6.5 years (first patient in to last patients out) to compare the efficacy and safety of Everolimus and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in combination with cyclosporine A (CsA) and prednisolone as immunosuppressive treatment for de novo lung transplant recipients in Hannover, Germany. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hannover Medical School. The full trial protocol can be accessed from www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00402532. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects after the lung transplant procedure and prior to randomization.

Study population

Adult (18–65 years) male or nonpregnant female patients following de novo single- or double-lung transplantation were considered for this study. Patients with maintenance immunosuppressive therapy before the transplantation, induction therapy or prior treatment with an experimental drug within 30 days, leukopenia with <4/nL leukocytes, thrombocytopenia with platelet count <60/nL, any platelet transfusions or use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and uncontrolled infection before study entry were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were patients with multiorgan transplantation, systemic infections, wound healing failure of bronchial anastomosis, need for invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation support upon time of randomization and patients after retransplantation. By excluding all forms of mechanical respiratory support at the time of randomization during the first 2 weeks after lung transplantation, all patients with severe primary graft dysfunction were not considered for the study. Follow-up was 2 years or until death, exclusion or loss of follow-up.

Study design

Patients were enrolled in the study during the first 2 weeks after successful lung transplantation. All patients were on triple-drug immunosuppression according to the center's protocol using cyclosporine A, MMF and steroids. Randomization into two study arms was performed on posttransplant day 28. Randomization was performed by the Institute of Biometrics, Hannover Medical School, using block randomization with a fixed block size of 4. In the control group, the immunosuppressive regimen was maintained unchanged; in the Everolimus group, MMF was replaced by Everolimus, and the CsA dose was lowered. All patients were followed up for 2 years. Evaluations were performed in regular 3-month intervals at the outpatient clinic of the institution until dropout or completion of 24 months follow-up.

Patients with repeat acute rejection episodes (two or more within 3 months of follow-up) were seen as having insufficient immunosuppression therapy and were excluded from the study. They were included in Tacrolimus-based protocols.

Medication

CsA was started continuously via 2-h perfusion 12 h after lung transplantation with an initial dose of 50 mg. The following doses were adapted to the C0 level of 250–300 ng/mL and applied via 2-h perfusion twice daily. The oral administration was initiated after extubation. Prednisolone was administered with a dose of 1 g intravenously prior to transplantation, followed by 125 mg three times in a 12-h interval. Thereafter, the prednisolone therapy was continued with a daily dose of 0.5 mg/kg and was reduced about 5 mg twice a week. The maintenance dose of 0.3 mg/kg was continued until 8 weeks posttransplantation and then reduced to 0.05 mg/kg after 3, 4, 6 and 12 months following the transplantation. The application of MMF was started the first day after transplantation with 500 mg twice a day and increased to a daily dose of 2 g. CMV prophylaxis was performed with valganciclovir. CMV prophylaxis was withdrawn in all patients (r+ and mismatches) at 3 months. In the case of CMV infection, ganciclovir 5 mg/kg (Cymevene®, Roche, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany) bid was given for 2 weeks.

In the Everolimus arm, a change of the immunosuppressive protocol was initiated at the day of randomization on posttransplant day 28: The initial dose of Everolimus was 0.75 mg twice daily. The blood level of Everolimus was examined on days 4 and 7, followed by weekly analysis and adapted to a blood level of 6–8 ng/mL. The CsA blood level (C0) was reduced to 200–250 ng/mL after 6 months and to 150–200 mg/mL after 12 months in the MMF arm, while the CsA blood level was reduced to 150–200 ng/mL and to 100–150 ng/mL in the Everolimus arm, respectively.

Objectives of the study

The primary endpoint of this trial was the incidence of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Secondary endpoints included the incidence of death and abortion due to adjustment of the immunosuppressive therapy in the first 2 years after transplantation. Additionally, the safety and tolerance of Everolimus with special regard to nephrotoxicity and infections were analyzed. Therapy failure was defined in both arms when (two or more) recurrent episodes of rejection occurred within a time frame of 3 months. These patients were treated within a different rescue protocol.

Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome

BOS was defined according to the current criteria established by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation 10. BOS was defined as a forced expiratory volume at 1 second intervals (FEV1) <80% in relation to the baseline FEV1, defined as the average of the two highest measurements obtained at least 3 weeks apart during the postoperative course. Spirometry was performed according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines 11. The endpoint BOS was determined locally as well as by independent data review: Two international experts (AF and EV), not involved in any other aspect of the study and blinded to treatments, were asked to grade any participant at the end of follow-up as having BOS (yes/no/not available) and, if yes, to determine the date of onset. The incidence of BOS was calculated in the total intention-to-treat population (n = 190) and in all patients who completed 2 years follow-up on the study medication (per protocol). A final grading of BOS was made if at least two of three reviewers agreed. The earliest date of BOS onset rated by the reviewers was taken into account for final BOS-free survival analysis, which is defined as a secondary composite endpoint as freedom from BOS and death following lung transplantation with no correction used for missing values owing to death.

Acute rejection

Biopsy-proven acute rejection was defined as any biopsy higher or equal to grade A1 according to International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation criteria 12. In the absence of biopsies, acute rejection was defined as a decrease in FEV1 by 15% or more in an acute setting with no signs of infection and reversibility after treatment with high-dose steroids for 3 days.

Infections

Infections were defined as any new anti-infective therapy except inhaled antibiotics for colonization and prophylactic medications. CMV infection was defined as any CMV viremia or antigenemia; CMV disease was defined as any CMV detection in tissue or CMV infection with symptoms (e.g. cytopenia, abnormal liver function test, fever, or malaise).

Renal function

Kidney function was assessed by the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using the CKD–EPI equation, as previously published 13.

Data analysis

Sample size calculation

We estimated that an enrollment of 190 patients (1:1 allocation ratio) would be needed for the study to have a statistical power of 80% (one-sided significance level of 0.05) to detect an absolute reduction of 15% incidence of BOS in the treatment group, assuming a background incidence of 25%. The intention-to-treat population was used for all efficacy analyses, except if otherwise mentioned (per protocol). A two-group continuity-corrected chi-squared test was used for the sample size calculation (nQuery Advisor v4.0, Statistical Solutions, Boston, MA, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented as median and interquartile. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and evaluated with Fisher's exact test. Continuous data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. According to the Bonferroni correction with a two-sided significance level of 0.10 (13 tests: 0.10/13 = 0.0076923…), p-levels less than 0.0077 were deemed to be significant. Estimations of survival curves were performed with the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to compare the survival curves of the two treatment groups. IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and STATA version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software were used to analyze the data.

Results

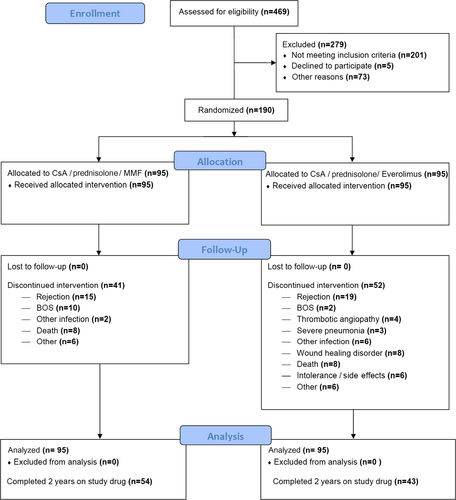

A total of 190 patients after de novo lung transplantations were enrolled in a single center in a time period of 4.5 years. A flowchart of the study is displayed in Figure 1. Forty percent of the individuals undergoing lung transplantation during the study period were included. The patients were randomized so that 95 patients were in each the MMF group and the Everolimus group. Groups were well balanced according to baseline demographics (Table 1).

| Characteristics | MMF (n = 95) | Everolimus (n = 95) | All patients (n = 190) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age—No. (%) | 60 (47–64) | 56 (45–62) | 57 (46–63) |

| Gender female—No. (%) | 39 (41.1) | 42 (44.2) | 81 (42.6) |

| Transplant type—No. (%) | |||

| Bilateral | 86 (91) | 80 (84) | 166 (87) |

| Unilateral | 9 (10) | 15 (16) | 24 (13) |

| Diagnosis—No. (%) | |||

| Cystic fibrosis | 24 (25) | 24 (25) | 48 (25) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 20 (21) | 25 (26) | 45 (24) |

| Emphysema | 39 (41) | 37 (39) | 76 (40) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Other | 10 (11) | 9 (10) | 19 (10) |

| FEV1 predicted—% (IQR) | 93 (75–108) | 89 (75–103) | 90 (75–105) |

| CMV D negative/R negative—No. (%) | 7 (7) | 18 (19) | 25 (13) |

| CMV R positive—No. (%) | 74 (78) | 66 (69) | 1140 (74) |

| CMV D positive/R negative—No. (%) | 14 (15) | 11 (12) | 25 (13) |

- MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 second intervals; IQR, interquartile range; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Ninety-seven patients (51%) completed 2 years on drug treatment, defining the per-protocol (PP) population. The most frequent reasons to discontinue were recurrent acute rejection or BOS onset (49%). Discontinuation occurred more frequently in the Everolimus group (55%) than in the MMF group (43%). Wound healing problems led to discontinuation of Everolimus in 8% of patients. Discontinuation was performed median on day 118 (interquartile 41–322).

Patient survival

Twenty-two deaths occurred during the follow-up period—12 in the MMF group and 10 in the Everolimus group. Two-year survival did not differ between groups—89% in the Everolimus group and 87% in the MMF group (p = 0.664). The most frequent causes of death were sepsis (n = 6, Everolimus n = 4), respiratory failure due to chronic allograft dysfunction (n = 8, Everolimus n = 3), cardiovascular failure (n = 3, Everolimus n = 1) and malignancy (n = 2, Everolimus n = 0). In the PP population, 2-year survival was 87% and 93% for MMF and Everolimus, respectively (p = 0.30).

BOS verification

In four cases (2%), BOS status could not be determined (n = 1 airway complication, n = 3 single FEV1 measurements). Agreement between the reviewers about BOS (yes/no/not available) status was 92.1%; agreement about the date of BOS onset was 64.4%. In 96.6% of the cases, locally determined BOS status was confirmed by independent data reviewers.

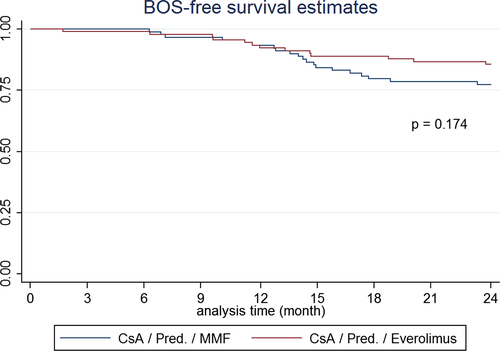

Acute and chronic organ dysfunction

In the ITT population, the incidence of BOS was 20/95 (21%) patients in the MMF group and 13/95 (14%) in the Everolimus arm (p = 0.250; −7.3% difference, 90% confidence interval [CI]: −18.1% to 3.4%). As for the PP population, the incidence of BOS was 8/54 (15%) in the MMF group and 1/43 (2%) in the Everolimus arm (p = 0.041; 12.5% difference, 90% CI: 3.7% to 21.3%). In the Everolimus group, fewer biopsy-proven rejection episodes were observed, while the number of steroid pulse courses did not differ between groups (Table 2). Analyzing the PP population, 2-year BOS-free survival was 98% in the Everolimus group and 89% in the MMF group (p = 0.09). BOS-free survival patterns for the ITT population show that the hazard for BOS is increasing over time in both groups (Figure 2).

| Item | MMF occurrences (%) | Everolimus occurrences (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infections, any episode—No. (%) | 264 (278) | 225 (237) | — |

| Patients with at least one infection—No. (%) | |||

| Bacterial, any | 39 (41) | 46 (48) | 0.307 |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 115 (121) | 88 (93) | 0.003 |

| Pneumonia | 21 (22) | 19 (20) | 0.722 |

| Viral, any | 14 (15) | 12 (13) | 0.673 |

| CMV antigenemia | 16 (17) | 4 (4) | 0.005 |

| CMV disease | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.155 |

| Herpes infection | 7 (7) | 8 (8) | 0.788 |

| Fungal infection, any | 23 (24) | 18 (19) | 0.378 |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 13 (14) | 25 (26) | 0.030 |

| Steroid pulse therapy | 21 (22) | 19 (20) | 0.722 |

| Steroid pulse therapy with ≥A1 | 16 (17) | 4 (4) | 0.005 |

| GFR, 12 months < 30 – n (%) | 4 (6) | 7 (14) | 0.148 |

| GFR, 24 months < 30 – n (%) | 4 (8) | 7 (17) | 0.168 |

- Thirteen tests (0.10/13 = 0.00769), Bonferroni correction: p-values < 0.0077 are deemed to be significant. MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; CMV, cytomegalovirus; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

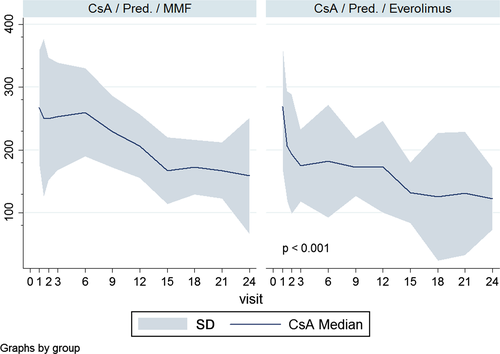

CsA exposure was intentionally reduced in the Everolimus group (Figure 3). A total number of 34 patients (15 MMF, 19 Everolimus) were excluded from the study for suspected recurrent rejection. It was believed to be unsafe to continue with cyclosporine-based immunosuppression, and patients were switched to Tacrolimus.

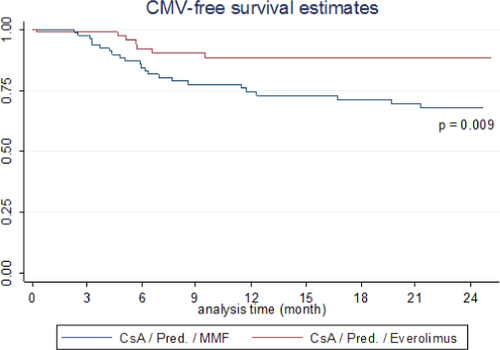

Posttransplant infections

Secondary outcomes are displayed in Table 2. Lower respiratory tract infections were significantly less frequent in the Everolimus-treated patients. CMV infections significantly increased in the MMF group (Table 2 and Figure 4). Fungal infections (all tracheobronchial) did not differ between groups.

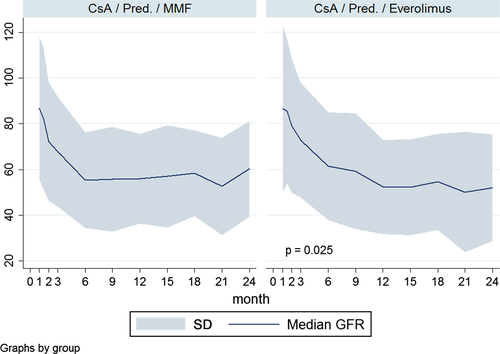

Posttransplant renal function

The calculated GFRs at the time of randomization were comparable in two groups (103 vs. 96 mL/min/1.73 m2) in the Everolimus and MMF groups, respectively. The 2-year GFR was not different at 1 year (52 vs. 56 mL/min/1.73 m2) and 2 years (52 vs. 56 mL/min/1.73 m2) between the Everolimus and MMF groups, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 5).

Safety

Safety data are displayed in Table 3: Adverse events were frequent and did not differ between groups. Half of the study subjects had at least one serious adverse advent (SAE). The total number of SAEs were similar in both groups but were distributed over more patients in the Everolimus group. As based on the judgment of two of the authors (M.S. and J.G.), more adverse events in the Everolimus group were counted as drug related. Moreover, 50 of the SAEs in the Everolimus group were seen as drug related, and only 18 in the MMF group (Table 3) were seen as drug related. Most of the nonmedically treated SAEs were episodes of obstructive airway complications (n = 7 in the MMF group and n = 11 in the Everolimus group) and were treated by balloon dilatation or argon therapy. All episodes of leucopenia (n = 25) were observed in the MMF group.

| Item | MMF (n = 95) | Everolimus (n = 95) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient with ≥ 1 AE—No. (%) | 80 (84) | 78 (82) |

| Patient with ≥ 1 SAE | 40 (42) | 55 (57) |

| Adverse events | ||

| No. of adverse events | 473 | 460 |

| No. of related adverse events | 236 | 199 |

| AE—No. of patients (%) | ||

| Concurrent medication | 68 (72) | 61 (64) |

| Nondrug therapy | 39 (41) | 32 (34) |

| Study medication interruption | 1 (1) | 6 (6) |

| Study medication reduced | 5 (5) | 6 (6) |

| Laboratory abnormality—No. of patients/total no. (%) | ||

| Leukocytes < 2 | 11 (12) | 0 (0) |

| SGOT (AST) ≥ 3 ULN | 74 (78) | 66 (69) |

| SGPT (ALT) ≥ 3 ULN | 74 (78) | 67 (71) |

| Creatinine > 265 μmol/l | 2 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Hemoglobin < 7 g/dL | 3 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Thrombocytes < 50/nL | 2 (2) | 4 (4) |

| Serious adverse events | ||

| No. of serious adverse events | 79 | 98 |

| No. of related serious adverse events | 18 | 50 |

| AE—No. of patients (%) | ||

| Death | 12 (13) | 10 (11) |

| Hospitalization | 43 (45) | 53 (56) |

| Concurrent medication | 25 (26) | 46 (48) |

| Nonmedical therapy | 23 (24) | 21 (22) |

| Temporal interruption of study drug | 2 (2) | 12 (13) |

| Dose reduction of study drug | 6 (6) | 11 (12) |

- MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; AE, adverse event; SGOT, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; ULN, upper limit of normal; SGPT, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

Five cases of posttransplant thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) were identified 74–360 days after lung transplantation in the Everolimus group. Laboratory values showed decreased haptoglobin and hemoglobin levels, thrombocytopenia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase and schistocytosis in the peripheral blood smear; three of these were confirmed by renal biopsy. No case of posttransplant TMA was observed in the MMF group. All patients developed acute kidney injury with increased serum creatinine levels by 59 to 94 μmol/L. Two patients required dialysis treatment. Two patients recovered from TMA; two did not recover and remained dialysis dependent. One patient deceased 3 days after diagnosis of posttransplant TMA due to cardiovascular collapse and unsuccessful resuscitation.

Discussion

This is a large prospective randomized study with Everolimus and reduced calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) de novo after lung transplantation. The substitution of a cell cycle inhibitor by a proliferation signal inhibitor and reduced CNI proved to be safe. No evidence of statistically significant reduction in the incidence of BOS and acute rejection was observed with treatment using the ITT analysis.

The original hypothesis of a reduction of BOS incidence by 15% within 2 years still seems reasonable; however, only about 50% of patients completed the study. The estimated dropout rate was more than doubled and therefore proves that the hypothesis failed. The analysis of the per-protocol cohort revealed a possible benefit for the Everolimus group (1/43) versus 8/54, p = 0.041. However, the higher rate of discontinuation in the Everolimus arm may have introduced a selection bias for the per-protocol analysis.

A similar result was seen in the most recent multicenter trial 14. By comparing similar immunosuppressive protocols, Glanville et al. could also not show any significant differences in BOS incidence in the ITT group 14. This study was also underpowered with a comparable dropout rate of more than 50%. However, in their per-protocol analysis, advantages were also seen for the Everolimus group for a potential reduction of BOS incidence. The high dropout rates in both studies stress the general challenge of these investigations.

Important observations were made in the secondary endpoints of our study. Use of Everolimus starting 28 days after lung transplantation is safe and allows further refinement of immunosuppressive protocols for this challenging patient population. Biopsy-proven acute rejections were even less frequent in Everolimus-treated patients 14. This finding was confirmed by Glanville et al.

Compared with older studies, two important changes were made in Glanville's study and in our protocol: The administration of Everolimus was not given as a fixed dose but in a trough level–adjusted manner 14-16. In addition, both protocols reduced the CsA exposure (22–28% in our study and 25–50% in Glanville's study) intentionally in the Everolimus arm 14-16. Lowering the CsA levels in the Everolimus arm did not lead to a higher rate of acute rejection (AR). The importance of the CsA reduction was seen in five early patients in this study without immediate reduction who developed thrombotic angiopathy 15. Once this serious adverse event became evident, additional cases could be avoided by ensuring the timely reduction of CsA exposure in all patients.

As a single-center, open-label study over a prolonged period of time, changes in patient management may have caused some bias. The unfamiliar Everolimus use in particular may have caused a bias of discontinuation of Everolimus in the early phase of the study and a potential hesitation of decreasing CsA levels in the Everolimus arm. This is an unproven hypothesis but may present a serious limitation of the study. It would explain, for example, the discrepancy of biopsy-proven AR and the number of suspected ARs (the number of steroid treatment episodes) in the Everolimus arm (Table 2). A total of 34 patients were withdrawn from the study because of suspected or proven recurrent rejection. This was seen as an important safety step for the study and was ultimately a limitation as well. These patients were treated with a Tacrolimus-based protocol, which may be more effective in lowering AR and subsequently also BOS 16. An additional limitation is that only patients with a beneficial perioperative course were selected for the study. It remains unknown if patients with primary graft dysfunction or other early perioperative limitations would show similar results. As the high dropout rate is the main limiting factor, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the agreement of reviewers on the onset of BOS was only 64.4%, indicating the importance of external review but also the difficulty of the parameter. Despite this, the high similarity in the results and the dropout rate seen in the multicenter trial of Glanville et al. and our findings is striking 14.

Another important observation is the reduction of CMV antigenemia in the Everolimus-treated population. This finding was confirmed after other solid organ transplants, like kidney 17 and heart 6. In addition, in the study of Glanville et al, a higher incidence of opportunistic infections was described in the mycophenolate arm when compared to the Everolimus arm, including CMV infections. In a post hoc analysis in another clinical trial, this finding was also seen when sirolimus was compared to azathioprine 18. In addition, we found fewer lower respiratory tract infections in the Everolimus group. It may be speculated that maintaining a better humoral immune response associated with Everolimus, which allows for significant rises in antigen-specific IgG antibodies, plays a role in mitigating CMV viremia 19 and lower respiratory tract infection.

A critical finding of severe leucopenia (<2/nL), which may be associated with comedication of MMF in the presence of anti-CMV prophylaxis using valganciclovir 20, could be prevented in Everolimus-treated patients and therefore prevent a potentially life-threatening complication after lung transplantation. Significantly less leucopenia and fewer episodes of diarrhea were also reported in Glanville's trial 14.

One of the adverse events of greatest concern is the development of renal insufficiency early after lung transplantation. Despite the fact that our study population showed intact kidney function at the time of enrollment, a remarkable drop in GFR was seen in both arms during the first 6 months after transplant. Thereafter, the values remained stable but unimproved. This indicates that current immunosuppressive protocols in addition to other nephrotoxic comedication impair kidney function significantly in the early phase after lung transplantation. A decrease of GFR by almost 50% was previously reported after lung transplantation 21, and 25% of patients are reported to show renal dysfunction (defined as an increase in creatinine) within 1 year after lung transplantation 22. It seems to be standard practice in many programs to start acting on CsA levels when serum creatinine levels start to rise. With this knowledge, we suggest using GFR as a parameter to prevent an early decrease in kidney function. Through the use of trough level–adjusted Everolimus exposure, we were able to avoid excess morbidity in the Everolimus group. However, the overall decline of kidney function remains worrisome.

In contrast to the Glanville study, we used CsA trough levels and not C2 target levels as suggested 14, 23, 24. This was decided for logistical and compliance issues to obtain CsA levels at the same time Everolimus trough levels were measured. It can be speculated that including C2 target levels in the trial could have enhanced efficacy 25 and renal protection.

In many studies, Everolimus has been used to reduce the nephrotoxicity of immunosuppressive protocols: A protocol that lowers CNI levels in the presence of Everolimus was suggested to improve kidney function 26. Given the fact that the time of highest nephrotoxicity coincides with the time of highest incidence of AR, a trade-off in efficacy and nephrotoxicity seems to determine the course. A novel approach was published and studied a quadruple approach of low-dose CNI, Everolimus, MMF and steroids to improve kidney function after thoracic transplantation: the Nordic Everolimus (Certican) Trial in Heart and Lung Transplantation (NOCTET) trial 27. Improvements in GFR were found as well as acceptable efficacy and safety data. However, the impact of this approach was limited to patients with a baseline GFR between 20 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and time since transplant of less than 4.6 years 28.

The findings of this study as well as the NOCTET trial led to the initiation of a multicenter trial in Germany to use a quadruple low-dose maintenance regimen including Everolimus in comparison to standard triple-drug maintenance therapy in order to ensure efficacy and avoid kidney injury in lung transplant recipients.

In summary, all clinical studies so far have failed to prove an advantage of proliferation signal inhibitors to reduce the incidence of BOS after lung transplantation. All studies demonstrated a high withdrawal rate from the clinical protocol, leaving the studies underpowered to prove the primary endpoint in an intention-to-treat analysis. In addition, our study as well as others required external review to determine the onset of BOS. Difficulty to pinpoint the onset of BOS as well as the current discussion about different forms of chronic allograft dysfunction question the role of BOS to be a useful primary endpoint parameter.

However, when per-protocol patients were analyzed, advantages and also specific risks in Everolimus patients were seen. It seems that no standard protocol works for the majority of patients, even in lung transplant patients highly selected for clinical trials. Individualized approaches still have to be used in most lung transplant recipients. The strength of Everolimus may be another option in the armamentarium for this purpose. Other advantages such as the avoidance of AR, CMV and lower respiratory tract infection and the absence of leukopenic episodes are hallmarks of this therapy. The risks of wound healing problems, kidney injury and thrombotic microangiopathy need to be addressed by the awareness and consequent reduction of CNI comedication. A switch from creatinine to GFR-based 29 follow-up protocols may be useful to protect kidney function. Quadruple immunosuppression may play a future role after lung transplantation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andrew Fisher, MD, Newcastle, United Kingdom, and Eric Verschuuren, MD, Groningen, the Netherlands, for their expert review of the onset of BOS in this study population and Jackeline Iseler, MSN, RN, and Cathy Wiesner, MS, for help with manuscript preparation. This study was also supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Nuremberg, Germany.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.