Renal Transplantation Using Belatacept Without Maintenance Steroids or Calcineurin Inhibitors

Abstract

Kidney transplantation remains limited by toxicities of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) and steroids. Belatacept is a less toxic CNI alternative, but existing regimens rely on steroids and have higher rejection rates. Experimentally, donor bone marrow and sirolimus promote belatacept's efficacy. To investigate a belatacept-based regimen without CNIs or steroids, we transplanted recipients of live donor kidneys using alemtuzumab induction, monthly belatacept and daily sirolimus. Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive unfractionated donor bone marrow. After 1 year, patients were allowed to wean from sirolimus. Patients were followed clinically and with surveillance biopsies. Twenty patients were transplanted, all successfully. Mean creatinine (estimated GFR) was 1.10 ± 0.07 mg/dL (89 ± 3.56 mL/min) and 1.13 ± 0.07 mg/dL (and 88 ± 3.48 mL/min) at 12 and 36 months, respectively. Excellent results were achieved irrespective of bone marrow infusion. Ten patients elected oral immunosuppressant weaning, seven of whom were maintained rejection-free on monotherapy belatacept. Those failing to wean were successfully maintained on belatacept-based regimens supplemented by oral immunosuppression. Seven patients declined immunosuppressant weaning and three patients were denied weaning for associated medical conditions; all remained rejection-free. Belatacept and sirolimus effectively prevent kidney allograft rejection without CNIs or steroids when used following alemtuzumab induction. Selected, immunologically low-risk patients can be maintained solely on once monthly intravenous belatacept.

Abbreviations

-

- ALC

-

- absolute lymphocyte count

-

- CMV

-

- cytomegalovirus

-

- CNI

-

- calcineurin inhibitor

-

- CoB

-

- costimulation blockade

-

- CoBRR

-

- CoB resistant rejection

-

- DSA

-

- donor-specific antibody

-

- EBV

-

- Epstein–Barr virus

-

- eGFR

-

- estimated GFR

-

- IVIg

-

- intravenous immunoglobulin

-

- MFI

-

- median fluorescence intensity

-

- MMF

-

- mycophenolate mofetil

-

- mTORi

-

- mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitors

-

- PCR

-

- polymerase chain reaction

-

- PRA

-

- panel reactive antibody

Introduction

Transplantation effectively treats most causes of end-stage renal disease, but its clear benefits are tempered by a continuous requirement for drug-induced immunosuppression 1-3. Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) are the centerpiece maintenance immunosuppressant, used in over 94% of transplant recipients 1. They effectively prevent graft rejection and are approved for use with glucocorticosteroids. However, both agents impact broad metabolic pathways causing significant chronic side effects. Nevertheless, transplant recipients typically remain dependent on the daily use of these drugs, often in combination with other immunosuppressive agents, for life 1.

Belatacept is a fusion protein administered by monthly infusion that has recently been approved for use as a CNI alternative 3-8. It blocks the CD28-B7 costimulation pathway, a highly specific effect that avoids most chronic side effects 5-9. Furthermore, extensive evidence suggests that costimulation blockade (CoB) fosters immune processes that reduce dependence on maintenance immunosuppression over time 10-12. Unfortunately, belatacept is less effective than CNIs in preventing early 5, 7, but not late 13, 14, acute rejection, and its approved use remains dependent on chronic steroids 15. The mechanisms of early CoB resistant rejection (CoBRR) have been shown to relate to the action of short-lived, alloreactive memory T cells that have differentiated beyond the requirements for CD28-B7 costimulation 16-19. While these cells are controlled by CNIs, CNIs are known to antagonize the mechanisms by which CoB facilitates long-term allograft acceptance 10-12, 20. Conversely, mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORi) have been shown to promote the effects of CoB, particularly when donor antigen is abundant or even augmented through donor hematopoietic cell infusion 10-12. Lymphocyte depletion has been shown to substantially reduce the risk of early acute rejection 21, 22, and in particular to allow for patients to be transplanted with mTORi without CNIs or steroids 23-25. We therefore reasoned that transient T cell depletion and treatment with mTORi would satisfy the requirements for control of CoBRR without inhibiting the progressive, salutary effects of CoB, and in doing so, promote a regimen that could lead to once monthly immune therapy devoid of the side effects of CNIs and steroids. Herein, we demonstrate that CoB can be used effectively to prevent kidney allograft rejection without CNIs or maintenance steroids, and that with time, selected patients can avoid rejection solely on a once monthly infusion of belatacept.

Methods

Patients and general medical care

Adult, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) seropositive recipients of a first, HLA nonidentical, live donor kidney allograft were prospectively consented to an Institutional Review Board-approved (IRB00005064) clinical trial (NCT00565773). Patients with a history of immunosuppression within 1 year prior to transplant, prior lymphodepletion, known immune deficiency, coagulopathy, malignancy or glomerulopathy with potential for recurrence were excluded from enrollment. Patients receiving grafts from cytomegalovirus (CMV) seropositive donors were required to be CMV seropositive, but CMV seronegative recipients were enrolled if their donor also was CMV seronegative. Transplantation was performed using standard surgical techniques. Perioperative surgical and medical management, excepting the immunosuppressive strategy described below, were consistent with standard transplant care. Allograft function and other relevant parameters were assessed in keeping with standard clinical practice augmented by the studies detailed below.

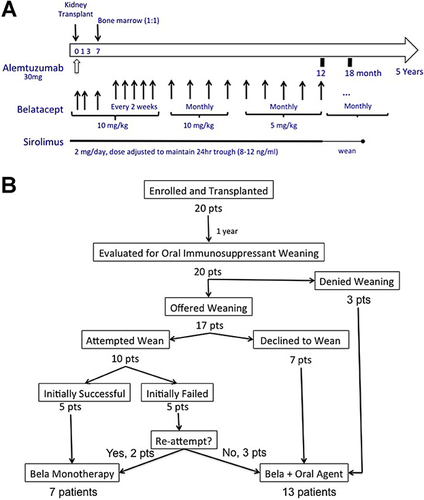

Immune management

Immune therapy (Figure 1A) began intraoperatively with a single 500 mg intravenous dose of methylprednisolone, 50 mg of diphenhydramine intravenously and 650 mg of acetaminophen rectally. One hour after premedication, a single 30 mg dose of alemtuzumab was given intravenously over 3 h.

Intravenous belatacept (10 mg/kg) was started on the first postoperative day, repeated on days 3, 7 and 14, every 2 weeks for four additional doses, and monthly through month 6; thereafter belatacept was given at a dose of 5 mg/kg monthly. Belatacept was intentionally given remote from alemtuzumab to avoid co-infusion of biologics and facilitate the ability to attribute any adverse events that occurred.

Oral sirolimus (2 mg/day) was started on postoperative day 1 and dose adjusted to maintain 24-h trough levels of 8–12 ng/mL. If the drug was not weaned, a lower trough of 3–8 ng/mL was targeted after 1 year. Sirolimus trough targets were dropped by up to 50% if side effects referable to this drug (e.g. mouth ulcers, arthralgias, anemia) occurred. If dose reduction was insufficient to control these effects, patients were converted to mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; 1000 mg twice daily) covered by an oral steroid taper (20 mg to off over 4 weeks).

One year after transplantation, patients without evidence of rejection on biopsy or donor-specific antibody (DSA) were offered the choice of continuing sirolimus (or MMF), or weaning from oral immunosuppression completely (Figure 1B). Weaning from oral immunosuppression required additional informed consent.

Bone marrow infusion

Bone marrow infusion was performed based on formal randomization controlled by the Emory investigational pharmacy service. Donors were not mandated to donate marrow and randomization was performed regardless of their desires in this regard. In the single incident that a donor refused marrow procurement, the recipient proceeded in the study without receiving marrow.

Donor bone marrow was procured from the iliac crest at the time of kidney donation. A dose of 1 × 108 nucleated cells/kg of recipient weight was targeted; the volume needed to achieve this result was estimated from a cell count on the product performed after approximately 200 mL had been collected. The marrow was collected and filtered using a sealed system, and anticoagulated in heparinized media. Following the procurement, the product was cryopreserved in a solution containing albumin and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, and stored at ≤140°C. On postoperative day 7, the product was thawed and infused at a dose of 1 × 108 nucleated cells/kg using standard techniques 26 in the outpatient clinic after the scheduled belatacept infusion. Recipients were premedicated before marrow infusion with diphenhydramine, hydrocortisone and ondansetron. Patients were monitored for complications for 4 h after the infusion. Based on the absence of myelospecific conditioning, chimerism was not anticipated, but was assessed using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay for short-tandem repeat polymorphisms weekly for 1 month and monthly for 3 months.

Surveillance biopsy and treatment of rejection

Patients underwent surveillance renal biopsies at 6 months, and annually for 3 years. Biopsies were required as a condition of sirolimus weaning. Biopsies were scored by the clinical pathology service as described 27. For the purposes of determining eligibility for weaning, any rejection, including borderline changes, contraindicated weaning. Suspected rejection was verified by biopsy and treated based on the standard of care.

Viral monitoring

Patients were monitored monthly for BK virus viremia for 1 year, then every 3 months or as clinically indicated using a PCR-based assay specific for the BK Virus VP1 gene performed by the clinical lab. Any level detected was considered positive (levels < 1070 copies/mL were reported as “low positive”). Patients were monitored every 3 months, or more frequently if clinically indicated, for EBV and CMV viremia using PCR-based assays specific for the EBNA-1 gene or the Major Immediate Early gene, respectively. For both targets, positive results with values < 300 copies/mL were reported as “low positive.”

Alloantibody monitoring

Recipients were required to be DSA-free and have a calculated panel reactive antibody (PRA) ≤20% as a condition of enrollment. All samples were screened for the presence of alloantibody using a flow cytometric, microparticle-based screening assay (FlowPRA®; One Lambda, Inc, Canoga Park, CA) as described 28 every 3 months. Positive samples were studied to define individual specificities to HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, DQA, DQB1, DRB3, 4, 5 and/or DPB1 antigens using a Luminex™-based assay (Austin, TX). Antibody positivity was defined as a baseline normalized median fluorescence intensity (MFI) > 1000 29.

Flow cytometry

Absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) and lymphocyte phenotype were evaluated weekly for 4 weeks, monthly for 12 months, and every 6 months thereafter, as previously described 30. The fluorochrome labeled mAbs anti-CD3-Alexa 700, anti-CD3-PerCP, anti-CD4-V450, anti-CD4-PE, anti-CD8-APC Fluor780, anti-CD8-PacBlue, anti-CD16-FITC, anti-CD20 PECy7, anti-CD45-PerCP, anti-CD45RA-APC, anti-CD56-APC, anti-Ki67-FITC and anti-CD197 PECy7 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and anti-CD45RA-QDOT655 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used. ALC was determined using Trucount beads (BD Biosciences). Cells were interrogated using an LRSII Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA). Memory and regulatory phenotypes were defined as previously described 31-34.

Results

Administration and tolerance of the therapy

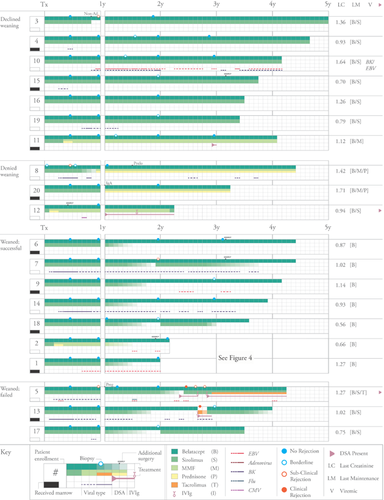

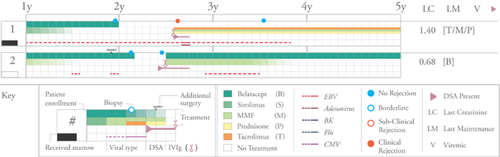

Twenty patients received a transplant. Their median age was 45 years (range 20–69). Twelve were male; 16 were Caucasian and 4 were African American. The donor–recipient pairs were mostly unrelated (13 unrelated, 7 related); HLA identical pairs were specifically excluded. The mean HLA mismatch was 3.6/6 with mean mismatches of 1.2, 1.5 and 1.1 for HLA A, B and DR loci, respectively. The clinical status of all patients is depicted in Figure 2. Graft function was immediate in all patients. All tolerated the transplant, induction therapy and belatacept infusions well. Seventeen patients tolerated sirolimus therapy. Three patients (pts. 2, 11 and 12) were switched to MMF at months 2, 1 and 5 for arthalgias, mouth ulcers and lymphocele, respectively. No result segregated with age, diagnosis or mismatch status. Nine patients received donor bone marrow, all without adverse event. Chimerism was not anticipated and was not detected in any patient.

Efficacy of the initial therapy in controlling alloimmunity

The base regimen was successful in preventing clinical allograft rejection (Figure 2). No patient experienced clinical, biopsy-proven, acute rejection, nor did any patient develop DSA within the first year. Nineteen patients had no functional concern for rejection within the first year. One patient (pt. 8) experienced a rise in serum creatinine (1.0–1.3 mg/dL) in the second postoperative week that prompted a biopsy revealing an interstitial macrophage infiltrate 24 that did not reach Banff criteria for rejection. He was treated with a 3-day course of methylprednisolone and returned to belatacept and sirolimus therapy.

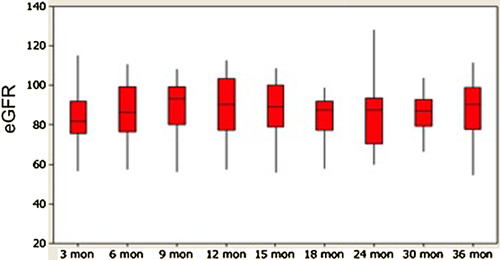

Subclinical rejection was detected on surveillance biopsy in the first year in three patients: one (also pt. 8) was found to have subclinical Banff grade 1B rejection at 6 months for which he received a 5-day oral prednisone taper. Two additional patients (pts. 3 and 5) were found to have subclinical Banff grade 1A and 1B rejections, respectively, 12 months posttransplant; patient 3 admitted to nonadherence with oral sirolimus in the prior 2 months. For these two patients treatment was limited to having their sirolimus reinstituted (pt. 3) and their sirolimus trough reduction delayed (both patients). All patients found to have subclinical rejection maintained stable function, remained on protocol therapy and resolved their histological findings on subsequent surveillance biopsies. All three episodes of subclinical rejection found on protocol biopsy were detected in patients who did not receive donor bone marrow; however, this secondary end point difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.22, Fisher's exact test). When considering all patients regardless of subsequent weaning, allograft function remained excellent. Mean serum creatinine was 1.10 ± 0.07 and 1.13 ± 0.07 mg/dL, and estimated GFR (eGFR; Nankivell formula) 35 was 89 ± 3.56 and 88 ± 3.48 mL/min at 12 and 36 months, respectively (Figure 3).

Effects of the initial therapy on protective immunity

There were no readmissions for opportunistic infection and no malignancies. However, protective immunity, which was intensively monitored, was measurably impaired. Ten patients were found to have transient BK viremia within the first posttransplant year (Figure 2). SV40 staining was detected on protocol biopsy in two patients, one each at 6 and 12 months, without detectable changes in renal function. All BK viremia resolved with expectant management or transient reduction in oral immunosuppression. Low-level, transient EBV viremia was detected in five patients (Figure 2) and resolved spontaneously. CMV viremia was detected in one patient (pt. 12) and resolved following an increase in prophylactic valganciclovir from 450 mg daily to 900 mg twice daily for 1 month. One patient (pt. 5) contracted and resolved influenza posttransplant.

One patient (pt. 8) developed pyelonephritis. This patient had been discontinued from sirolimus and converted to infliximab, MMF and prednisone to treat a flair of ulcerative colitis. His pyelonephritis resolved, his allograft function remains excellent (creatinine 1.37 mg/dL) and his colitis has been in remission for 3 years.

Results of oral immunosuppressant weaning

At 1 year, seven patients were offered the opportunity to wean their oral immunosuppression, but declined to do so (Declined weaning, Figure 2). These patients were satisfied with their immune management consisting of a single oral drug plus monthly belatacept and/or did not want to be encumbered by the increased surveillance required during the weaning period. All remained rejection-free without DSA (follow-up 38–58 months). Six of these patients were on sirolimus and one had converted to MMF. Their serum creatinine was 1.15 ± 0.11 mg/dL at 36 months posttransplant.

Three patients were denied weaning for associated medical conditions (Denied weaning, Figure 2) including ulcerative colitis (pt. 8), histological evidence of IgA nephropathy on surveillance biopsy (pt. 20) and low-level DSA (DQ specific antibodies with MFIs of 2062–3092; pt. 12), respectively. The trial was written so that immunosuppression reduction would not be offered if the attending transplant physicians or the principal investigator felt that the risk–benefit ratio of immunosuppressive reduction was potentially adverse, and in these cases there was consensus that the medical conditions did not favor reduced immunosuppression. All remained rejection-free, two on belatacept, MMF and prednisone (IgA and colitis), and one on belatacept and MMF (DSA) with excellent function.

Five patients (pts. 1, 2, 6, 9 and 14) were successfully weaned to belatacept monotherapy without incident. They maintained stable, excellent allograft function for over 1 year without DSA on monotherapy belatacept. Follow-up biopsies showed no rejection and their clinical courses on belatacept were unremarkable.

Five patients initially failed sirolimus weaning. Two failures were due to subclinical, borderline changes on surveillance biopsy prompting reinstitution of oral sirolimus, 1 mg/day. One of these patients (pt. 18) discontinued their sirolimus after 1 year of observation and moved to monotherapy belatacept. One (pt. 17) elected to stay on sirolimus. Three weaning failures experienced biopsy-proven rejection. One clinical rejection (Banff 2A with DSA) occurred 10 months after weaning and was treated with a methylprednisolone taper and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg). The rejection and DSA resolved, the patient (pt. 13) has remained clinically stable for 11 months (creatinine 0.95 mg/dL), and is again weaning sirolimus. One (pt. 7) was found to have a sub-clinical Banff 1A rejection without DSA postweaning and was treated with methylprednisolone. One year afterward this patient elected again to wean, and achieved belatacept monotherapy. The remaining wean failure (pt. 5), a clinical Banff 2A rejection with DSA, was treated with methylprednisolone and IVIg. The renal function improved, but the DSA persisted despite IVIg and rituximab. This patient had tacrolimus added to her regimen and maintained stable graft function thereafter (creatinine 1.22 mg/dL); a low level (MFI 2264) DSA to Bw6 persists. Of note, this patient became pregnant 12 months posttransplant and underwent an elective abortion, both potentially sensitizing events. Thus, of the five weaning failures, all achieved stable allograft function and two subsequently re-weaned to belatacept monotherapy. In all, seven patients weaned to belatacept monotherapy (Weaned; successful, Figure 2) and three patients failed weaning (Weaned; failed, Figure 2).

Two of the patients who were successfully weaned to monotherapy belatacept were followed for 1 year on belatacept, confirmed by biopsy to be rejection-free and by HLA testing to be DSA-free, and then reconsented to discontinue belatacept (Figure 4). The first patient (pt. 1), a bone marrow recipient, had an unremarkable clinical course off all immunosuppression for 7 months, at which time, coincident with an upper respiratory infection, he developed a Banff 2A cellular rejection with DSA prompting treatment with rabbit antithymocyte globulin, IVIg and plasmapheresis. He was converted to a tacrolimus regimen as dictated by the protocol. His rejection and DSA resolved, and he has maintained stable allograft function at a baseline creatinine of 1.40 mg/dL for over 2 years. The second patient (pt. 2) remained off all immunosuppression for 4 months, at which time she developed low-level DSA without biopsy findings. She was treated with IVIg and returned to belatacept and MMF (sirolimus intolerant). Her DSA resolved. After 1 year she was weaned back to monotherapy belatacept and has remained clinically stable (creatinine 0.68 mg/dL) without DSA for over 1 year.

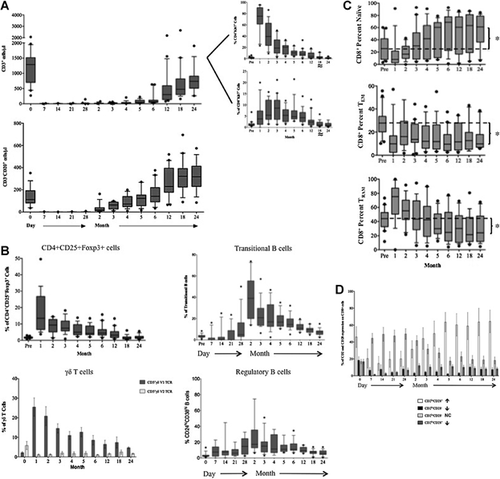

Lymphocyte repopulation

T and B cells were depleted peripherally following alemtuzumab induction (Figure 5A). Depletion and repopulation kinetics varied as a function of cell surface phenotype. As has been described 30, T cells expressing a terminally differentiated (CCR7−, CD45RA+) 31 effector phenotype enriched for CD28−CD8+ 34 T cells predominated for approximately 3 months. Homeostatic activation and repopulation occurred with a time course similar to that described 24, with ALCs returning to pretransplant levels in 12 months. Homeostatic T cell activation (CD69+Ki67+) persisted 6 months beyond ALC normalization (Figure 5A). Several cell populations with potential regulatory function were disproportionately increased commensurate with the period of homeostatic activation (Figure 5B) including CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells, CD3+Vδ1+ T cells (with an increased Vδ1+/Vδ2+ ratio), transitional (CD27−CD38+IgDhi) B cells and B regulatory cells (CD20hiCD24hiCD38hiIgMhi) 32, 33.

CD4+ T cells reconstituted a repertoire phenotypically indistinguishable from that seen pretransplant (not shown). However, CD8+ T cells repopulated enriched for naïve phenotype T cells expressing CD28 (Figure 5C and D). There was a proportionate decrease in CD28− effector or memory T cells. B cells repopulated more rapidly than T cells, reaching, and then exceeding, baseline levels by 6 and 18 months, respectively. Repopulated B cells were predominantly naïve, with significantly reduced numbers of memory B cells. Thus, the final lymphocyte repertoire was characterized by more naïve T and B cells, fewer differentiated T and B effectors and increased expression of CD28, the receptor pathway targeted by belatacept.

Discussion

We have shown that kidney transplantation can be performed using a belatacept-based regimen without reliance on maintenance CNIs or steroids. Additionally, we have shown that when adjuvant agents are chosen to exploit the mechanisms known to facilitate experimental CoB-based therapies, immunosuppressive requirements decrease with time, allowing selected, immunologically low-risk patients to remain rejection-free solely on monthly low-dose 7 belatacept. Several aspects of this experience deserve comment.

First, the base regimen, one that can be deployed without preconditioning using only agents approved for clinical use, clearly controls rejection in live donor recipients. This is demonstrated by the success of all patients in the first year, and emphasized by the prolonged clinical stability of those patients who, thereafter, did not wean from their oral immunosuppression. Thus, we believe the base regimen to be a logistically feasible immunosuppressive approach worthy of multicenter validation and expansion into the setting of deceased donor kidney transplantation.

Numerous preclinical studies have advanced the promise of CoB-based therapy as a means of preventing rejection without the burden of chronic immunosuppression, a goal regularly achieved in experimental animals. However, CoB's clinical translation has been hampered by early, high-grade acute rejections 5, 7, prompting intense investigation into the mechanisms differentiating the experimental from the clinic settings. Substantial data have implicated terminally differentiated, effector T cells, arising in part through differences in environmental antigen exposure between humans and experimental animals, as the prime mediators of CoBRR 18, 36. These cells have significant cytolytic potential and typically have lost CD28 expression during the course of late phase differentiation 34; as such, they are indifferent to the direct effects of CD28-B7 pathway blockade. However, their terminally differentiated state renders them largely nonproliferative and susceptible to gradual elimination by activation-induced cell death or apoptosis; mTORi and donor antigen exposure both are thought to foster this elimination 10-12, 37. This is the first clinical study to prospectively address these mechanisms and further to prospectively randomize the use of donor bone marrow. We have shown that, although bone marrow infusion is feasible and well tolerated, it may not be necessary for primary efficacy—a logistical advantage. While no measured parameter was significantly influenced by marrow infusion, we cannot comment definitively on trends associated with this maneuver in this proof-of-concept study. We thus view this as a matter worthy of further controlled investigation.

We find that the lymphocyte depletion achieved with this regimen promotes the ultimate emergence of a lymphocyte repertoire that is perhaps more accommodating to belatacept's intended effect, being characterized by more naïve T and B cells, and fewer differentiated CD28− T cells and memory B cells than seen prior to transplantation. While this does not eliminate the possibility of residual donor-alloreactive belatacept-resistant T cells, it is reasonable to consider that these repertoire changes contribute to the eventual capacity to maintain the patients on belatacept alone. Indeed, we have recently demonstrated that belatacept's immunosuppressive effect is greatest when considering naïve CD28+ T cells, and diminishes with progressive T cell differentiation and loss of CD28 expression 38. In addition, the regimen has allowed for the emergence of numerous cell types with potential regulatory function, and given the temporal, perhaps compensatory, association with homeostatic repopulation, we hypothesize that this is one reason we have not seen homeostatic activation-dependent CoBRR 39. Other factors that may foster late, as opposed to early, immunosuppression withdrawal include the absence of surgical trauma, peritransplant reperfusion or other similarly activating events at the time of withdrawal. Several patients (pts. 2, 6, 7, 12 and 15) have subsequently undergone additional surgical procedures, to include bilateral native nephrectomy or partial hepatectomy for massive polycystic disease, without acute consequences. Thus, in this setting, surgical trauma alone appears insufficient to provoke allograft rejection late after transplantation.

It is clear that this regimen, like every efficacious antirejection regimen, impairs protective immunity. No major infectious events were seen, but the relative degree of impairment of this regimen compared to the myriad regimens used in kidney transplantation remains speculative. As reactivation of CMV and EBV was not notable, it is unlikely that a marked impairment of immunity to latent herpesviruses exists. However, the presence of transient BK viremia in 10 patients suggests that the agents used in this combination could disproportionately influence immunity toward this particular virus. Additional experience will be required to understand this further, but it is worth noting for future trials. All episodes of BK virus were subclinical, detected only due to aggressive surveillance, so a sampling bias may be in effect. Also, all episodes resolved with reduction of the sirolimus dose, suggesting that sirolimus was contributing to the burden of immunosuppression and not providing an anti-BK effect as has been suggested 40. It is important to point out that the vast majority of the episodes of viremia occurred at the limit of detection of the PCR assays employed (dotted lines in Figures 2 and 4), and reflect aggressive surveillance with highly sensitive methods rather than clinical viral illness. In addition, at the end of follow-up, only one patient had any detectable viremia (pt. 10, a patient with BK and EBV detected below the level of quantification and who was eligible to wean sirolimus had they wished to), indicating a resolution of viral protective immune capacity without a resurgence of rejection or alloantibody formation.

Several aspects of this study prevent its immediate generalizability. This is an uncontrolled, single-center, proof-of-concept experience, albeit one that included Caucasian and African American patients of both genders across a broad age range (18–69). Nevertheless, numerous aspects of the decision-making have been left to the attending physicians (specifically with regard to preventing three patients from weaning in pursuit of beneficence) or the patients themselves (particularly the ability for patients to opt out of weaning at 1 year even if they were eligible, preserving patient autonomy). Also, while the general care that these patients received was consistent with the prevailing clinical standard with regard to infectious prophylaxis and clinical follow-up, monitoring was more intensive in several ways, including serial monitoring for DSA and viremia, and regular surveillance biopsies. It is not clear whether the subclinical findings of these techniques helped prevent progression to clinical disease and are important to this approach, or were indicative of self-limiting conditions that prompted unnecessary alterations in the therapeutic course. Our bias would be to maintain a similarly intensive monitoring scheme until multicenter validation can be secured. Our two patients who were withdrawn from all immunosuppression indicate that continued immune therapy is required. Nevertheless, the rigor of that immune therapy appears to be substantially reduced compared to the clinical standard. We cannot comment on the potential clinical course of the seven patients who chose not to wean or the three who were prohibited from weaning except to say that they have excellent graft function and tolerable immunosuppressive regimens. Whether they would have tolerated elimination of oral immunosuppression is a matter of speculation.

These data are consistent with the favorable short-term results of Ferguson et al 41 in suggesting that depletional induction is an effective means of reducing early belatacept resistant rejection, and that mTORi are appropriate maintenance agents to pair with belatacept. They are distinct from the relatively poor results of Ciancio et al 42, whose trial used alemtuzumab, donor stem cell infusion and tacrolimus conversion to sirolimus in the absence of belatacept. In this latter trial, failure due to recurrent glomerulopathy (a contraindication to inclusion in our trial) was seen, pointing out that immunosuppressive agents are at times best not withdrawn, and rejection was seen, suggesting that belatacept is an important aspect of this regimen. Our results extend these concepts well beyond the acute setting of both trials, clearly demonstrating a durable effect beyond the completion of homeostatic lymphocyte repopulation. Most importantly, they suggest that prolonged avoidance of CNIs and steroids in the presence of belatacept does more than limit morbidity; rather it allows for the requirements for immunosuppression to relax with time, facilitating a once monthly immune therapy for human transplantation. We believe that this approach is worthy of additional consideration.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by United States Food and Drug Administration Office of Orphan Products Development grant 1RO1FD003539 (ADK). Belatacept was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb. This trial is registered as NCT00565773 on ClinicalTrials.gov. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Satyen S. Tripathi, MA, CMI in creation of the figures.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.