Expectancies for alcohol analgesia and drinking behavior among veterans with chronic pain: The moderating role of discrimination in medical settings

Abstract

Background and Objectives

Chronic pain and alcohol use are highly prevalent and frequently co-occur among U.S. military veterans. Expectancies for alcohol analgesia (i.e., degree to which one believes that drinking can reduce or manage pain) may contribute to alcohol consumption, dependence, and related harms. Discrimination in medical settings (i.e., inequitable treatment in healthcare contexts) has been linked to deleterious health outcomes and may amplify associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and indices of hazardous drinking. Our goal was to test discrimination in medical settings as a moderator of associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and drinking behavior.

Methods

Participants included 430 U.S. military veterans with chronic pain and past month alcohol consumption (24% female; 73% White; Mage = 57) who completed an online survey via Qualtrics Panels.

Results

Expectancies for alcohol analgesia were positively associated with alcohol consumption, dependence, and related harms. Discrimination in medical settings moderated associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and alcohol consumption and dependence.

Discussion and Conclusions

Among veterans with pain, expectancies for alcohol analgesia were positively associated with indices of hazardous drinking, and discrimination in medical settings moderated associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and alcohol consumption and dependence. Future research should explore the potential utility of interventions addressing expectancies for alcohol analgesia and discrimination in medical settings in the context of pain and drinking.

Scientific Significance

These findings are the first to demonstrate that experiences of discrimination in healthcare contexts amplify relations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and drinking behavior among veterans with pain.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic pain and hazardous drinking (i.e., patterns of alcohol use associated with a greater risk of negative consequences) are highly prevalent and commonly co-morbid among U.S. military veterans.1, 2 Indeed, 31% of veterans (vs. 20% of non-veterans) report having chronic pain,3 and nationally representative estimates indicate that approximately 1 in 4 veterans engage in hazardous drinking.4 Converging lines of research support a reciprocal model,5 which posits that chronic pain and alcohol use interact bidirectionally, leading to the escalation/worsening of both over time.5, 6 For example, laboratory studies have demonstrated that the experience of pain increases alcohol consumption,7 and neurobiological evidence suggests an overlap between pain processing pathways and neural pathways associated with alcohol dependence.6, 8

Drawing from social cognitive theory,9 a robust body of literature has highlighted the importance of outcome expectancies (i.e., anticipated consequences as a result of engaging in a given behavior5, 9) in the initiation, maintenance, and escalation of alcohol use.10, 11 Emerging evidence further implicates expectancies for alcohol analgesia (i.e., expectation that drinking alcohol will reduce or help one cope with pain12), as an important correlate of hazardous drinking,5, 13, 14 particularly among individuals with chronic pain.12, 13 Alcohol has been shown to produce acute analgesic effects,15 and recent experimental research has demonstrated that individuals who anticipate that drinking alcohol will help them manage pain also tend to perceive greater pain relief after consuming alcohol.13 Notably, nearly a quarter of U.S. veterans in primary care report use of alcohol to manage pain,16 thus underscoring the importance of examining expectancies for alcohol analgesia among veteran populations.

Discrimination refers to the unfair or inequitable treatment experienced by an individual due to a salient stigmatized identity, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or disability status. A sizable literature has documented links between various forms of discriminatory experiences and hazardous alcohol use,17 including interpersonal instances of racial/ethnic and gender discrimination and internalized homophobia. Despite prior work highlighting the importance of examining specific types of discrimination and their role in drinking behavior,17 no research to date has examined associations between discrimination in medical settings (i.e., the degree to which an individual experiences discriminatory treatment while seeking healthcare18) and hazardous alcohol use. This study gap is surprising, as discrimination in medical settings has been linked to deleterious health behaviors, such as tobacco smoking,19 and treatment-related factors, such as lower patient satisfaction and reduced healthcare utilization.20, 21 Thus, veterans with chronic pain who have experienced discrimination in medical settings may be less inclined to seek pain treatment, potentially increasing their reliance on alcohol as a pain-coping mechanism. It is also possible that past experiences of discrimination in medical settings influence associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and drinking behavior. For example, veterans who hold expectancies for alcohol analgesia may be more likely to turn to alcohol for self-medication rather than seeking pain treatment from a healthcare provider, if they have had past experiences of discrimination in medical settings. However, no prior work has examined associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia, discrimination in medical settings, and hazardous drinking.

The goal of the current study was to test the following hypotheses: (1) scores on measures of expectancies for alcohol analgesia and discrimination in medical settings will each be positively associated with indices of hazardous drinking (i.e., consumption, dependence, and alcohol-related harms); and (2) associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and indices of hazardous drinking will be moderated by scores on a measure of discrimination in medical settings.

METHOD

Participants and procedure

Data were derived from an online survey of pain and alcohol use among U.S. military veterans with chronic pain. Participants were recruited using Qualtrics Panels, which employs a panel aggregator system to produce a national database of individuals who are willing to participate in survey-based research. Qualtrics Panels has been successfully leveraged for health-related research among veteran populations.22 Eligibility criteria included (1) being aged 18 or older, (2) current United States resident, (3) U.S. military veteran, (4) chronic musculoskeletal pain persisting greater than 3 months, and (5) past-month alcohol use. Individuals were excluded if they had previously received cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain or could not read English well. Participants were first screened for eligibility, and those who were deemed eligible and provided electronic informed consent were then directed to a 25-min web-based survey. Upon completion of the survey, participants were compensated according to prior agreements with Qualtrics. Consistent with previous web-based surveys among veteran populations,22 veteran status was verified by instructing participants to report the date listed on their DD 214 form. Individuals whose DD 214 did not align with their self-reported age or years of service were excluded. Likewise, individuals who failed an attention check (e.g., “to monitor quality, please respond with a two for this item”) or completed the survey in under 1/2 of the median completion time were excluded. All study procedures were approved by a University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Expectancies for alcohol analgesia

The Expectancies for Alcohol Analgesia scale (EAA)12 includes five items which measure the degree to which individuals believe that alcohol can help them reduce or manage pain (e.g., “when I feel pain, drinking alcohol can really help”). Items are scored on a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (extremely unlikely) to 9 (extremely likely) and are summed to generate a composite EAA score ranging from 0 to 45, with higher values reflecting greater expectancies for alcohol analgesia. The EAA has been psychometrically validated among individuals with chronic pain,12 and demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current sample (α = .97).

Discrimination in medical settings

Adapted from the widely used Everyday Discrimination Scale,23 The Discrimination in Medical Settings Scale (DMS)18 reflects the degree to which an individual experiences discriminatory treatment in healthcare or medical contexts. Seven items (e.g., “you feel like a doctor or nurse is not listening to what you were saying”) are scored on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), generating a range of 7–35, with higher scores indicating more frequent experiences of discrimination in medical settings. Adapted based on feedback from experts and individuals with chronic medical conditions, the DMS has shown good convergent and discriminant validity, and test–retest reliability,18 and has been used in various clinical populations,20, 21 including among veterans.19 In the current sample, the DMS demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .93).

Hazardous drinking

The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT)24 includes three subscales, including three items that assess patterns of consumption (AUDIT-Consumption; e.g., “how often do you have a drink containing alcohol”), three items measuring dependence (AUDIT-Dependence; e.g., “how often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started?”) and four items measuring alcohol-related harms (AUDIT-Harms; e.g., “how often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking?”). Items are summed to generate AUDIT-Consumption and AUDIT-Dependence scores ranging from 0 to 12, and AUDIT-Harms scores ranging from 0 to 16, with higher scores reflecting greater consumption, dependence and alcohol-related harms. In the current sample, the internal consistency of AUDIT-Consumption, AUDIT-Dependence and AUDIT-Harms was acceptable to good (α = .79, α = .86, and α = .73, respectively).

Chronic pain

The Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS)25 is commonly used to assess the presence and severity of chronic pain. The GCPS consists of three items assessing characteristic pain intensity (GCPS-CPI), and four items assessing pain-related functional interference (GCPS-Disability), which are scored from 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as can be). Items were summed to generate composite GCPS-CPI and GCPS-Disability scores, with higher values reflecting greater pain intensity and pain-related disability, respectively. The GCPS-CPI demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .85), and the GCPS-Disability demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = .92).

Sociodemographic and veteran-related variables

Sociodemographic information was collected, including age, gender identity, race, ethnicity, and income. Military service-related data included military era, military branch, combat and deployment history, and VA healthcare utilization.

Data analytic plan

Analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics Version 27 and PROCESS macro for SPSS.26 Before analysis, the distribution of all variables was examined for normality. The AUDIT-Dependence subscale exceeded recommended thresholds for skewness (≥|2|) and kurtosis (≥|3|), and AUDIT-Harms exceeded threshold for kurtosis. Square root transformations were applied to both AUDIT-Dependence and AUDIT-Harms subscale scores, which resulted in acceptable ranges for skewness and kurtosis.27 Next, separate hierarchical linear regression models were employed to examine the unique contributions of (a) EAA and DMS scores, and (b) their interaction in predicting AUDIT subscale scores. Age and gender were included as covariates due to established associations with pain- and alcohol-related outcomes.28, 29 Additionally, the GCPS-CPI and GCPS-Disability scores were included as covariates to isolate unique associations with expectancies for alcohol analgesia.

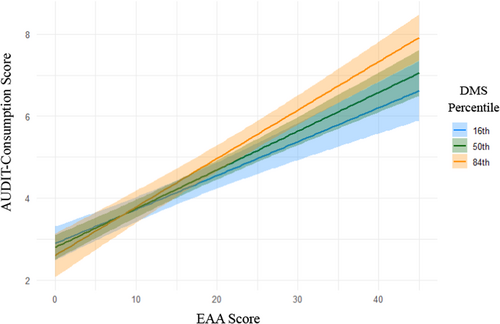

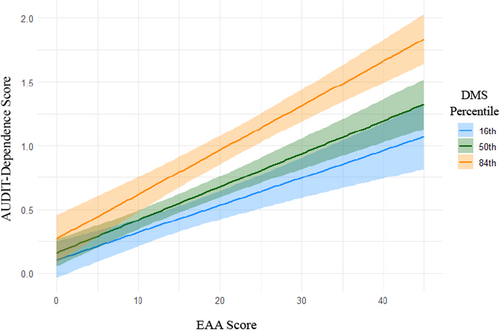

Model performance was assessed using change in R squared (ΔR2) and semi-partial correlations (sr2) at each step of the regression model to determine the variance explained by each model step (ΔR2) and each predictor (sr2). Significant interactions were further examined using the PROCESS macro for SPSS26 to test conditional effects of EAA scores across low, moderate and high levels of DMS scores. These associations were probed at the 16th, 50th and 84th percentiles, following recommended guidelines.26 Conditional effects were visualized using ggplot230 in R version 4.3.0.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Participants included 430 U.S. military veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain who reported drinking alcohol in the past month (24.2% women; 73.7% White; Mage = 56.7, SD = 13.8). The most endorsed military branch was Army (47.2%), followed by the Air Force (24.0%), Navy (22.3%), Marine Corps (8.6%) and Coast Guard (0.9%). The greatest proportion of veteran respondents served during the first (1991–2001) and second (2001–present) Gulf wars. Notably, military service era and military branch were not mutually exclusive categories, and some veterans reported having served in multiple eras or branches. The mean EAA score was 14.95 (SD = 14.47), and the mean DMS score was 12.65 (SD = 5.96). The average AUDIT-Consumption score was 4.33 (SD = 2.73), the average AUDIT-Dependence score was 1.31 (SD = 2.45), and the average AUDIT-Harms score was 1.87 (SD = 3.02). Additionally, participants reported moderately high levels of both pain severity and pain-related disability, with an average GCPS-CPI score of 18.61 (SD = 4.97) and average GCPS-Disability score of 18.06 (SD = 10.57). See Table 1 for additional sociodemographic, military service, chronic pain and alcohol-related characteristics.

| Total (N = 430) | |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Woman | 104 (24.2%) |

| Race | |

| White | 317 (73.7%) |

| Black or African American | 78 (18.1%) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 (1.2%) |

| Asian | 6 (1.4%) |

| Multiracial/other | 24 (5.6%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 29 (6.7%) |

| Income | |

| <$10,000 | 9 (2.1%) |

| $10,000–$25,000 | 62 (14.4%) |

| $25,000–$50,000 | 94 (21.9%) |

| $50,000–$75,000 | 110 (25.6%) |

| $75,000–$100,000 | 85 (19.8%) |

| >$100,000 | 70 (16.3%) |

| Military Brancha | |

| Army | 203 (47.2%) |

| Navy | 96 (22.3%) |

| Air Force | 103 (24.0%) |

| Marine Corps | 37 (8.6%) |

| Coast Guard | 4 (0.9%) |

| Military Eraa | |

| Vietnam (1964–1973) | 93 (21.6%) |

| Cold War (1985–1991) | 115 (26.7%) |

| First Gulf War (1991–2001) | 134 (31.2%) |

| OEF/OIF/OND (2001–present) | 137 (31.9%) |

| Another era not listed | 64 (14.9%) |

| Combat exposure | 104 (24.2%) |

| Deployment | 119 (27.7%) |

| VA healthcare | 225 (52.3%) |

| M (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 56.71 (14.80) |

| GCPS-CPIb | 18.61 (4.97) |

| GCPS-Disabilityc | 18.06 (10.57) |

| EAA Scored | 14.95 (14.47) |

| DMS Scoree | 12.65 (5.96) |

| AUDIT-Consumptionf | 4.33 (2.73) |

| AUDIT-Dependenceg | 1.31 (2.45) |

| AUDIT-Harmsh | 1.87 (3.02) |

- a Categories are not mutually exclusive;

- b Graded Chronic Pain Scale – Characteristic Pain Intensity Score;

- c Graded Chronic Pain Scale – Disability Score;

- d Expectancies for Alcohol Analgesia Scale- Total Score;

- e Discrimination in Medical Settings – Total Score;

- f Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption score;

- g Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Dependence score;

- h Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Harmful Use score.

Bivariate correlations

Bivariate analyses revealed that EAA score was positively correlated with DMS score (r = 0.33, p < .001), AUDIT-Consumption score (r = 0.62, p < .001), AUDIT-Dependence score (r = 0.54, p < .001), AUDIT-Harms score (r = 0.52, p < .001, GCPS-CPI score (r = 0.29, p < .001), and GCPS-Disability score (r = 0.31, p < .001). EAA score was negatively correlated with age (r = −0.31, p < .001). DMS score was positively correlated with AUDIT-Consumption score (r = 0.28, p < .001), AUDIT-Dependence score (r = 0.41, p < .001), AUDIT-Harms score (r = 0.38, p < .001), GCPS-CPI score (r = 0.21, p < .001) and GCPS-Disability score (r = 0.40, p < .001). DMS score was negatively correlated with age (r = −0.27, p < .001), and was correlated with female gender (r = −0.14, p = .004).

Expectancies for alcohol analgesia, medical discrimination, and alcohol consumption

Hierarchical linear regression analyses revealed that the EAA score was positively associated with AUDIT-Consumption score and accounted for 23% of the unique variance in AUDIT-Consumption score. DMS score was not significantly associated with AUDIT-Consumption score. Furthermore, a significant interaction between EAA score and DMS score on AUDIT-Consumption score was observed (β = .29, p = .01; see Table 2). Conditional analyses further revealed a positive association between EAA and AUDIT-Consumption score at low (b = 0.084, SE = 0.011, p < .001), moderate (b = 0.095, SE = 0.018, p < .001) and high (b = 0.119, SE = 0.010, p < .001) levels of DMS scores (see Figure 1).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t | sr2 | p | β | t | sr2 | p | β | t | sr2 | p |

| AUDIT-consumption | ||||||||||||

| Age | −.28 | −5.76 | 0.07 | <.01 | −.12 | −2.76 | 0.01 | .01 | −.13 | −3.10 | 0.01 | <.01 |

| Gendera | .27 | 5.89 | 0.07 | <.01 | .18 | 4.51 | 0.03 | <.01 | .18 | 4.54 | 0.03 | <.01 |

| GCPS-CPIb | .03 | 0.47 | <0.01 | .64 | −.03 | −0.66 | <0.01 | .51 | −.02 | −0.50 | <0.01 | .62 |

| GCPS-Disc | .17 | 3.04 | 0.02 | <.01 | .04 | .77 | <0.01 | .44 | .04 | 0.86 | <0.01 | .39 |

| EAAd | .54 | 13.0 | 0.23 | <.01 | .33 | 3.58 | 0.02 | <.01 | ||||

| DMSe | .08 | 1.90 | 0.01 | .06 | −.05 | 0.79 | <0.01 | .43 | ||||

| EAA × DMS | .29 | 2.58 | 0.01 | .01 | ||||||||

| R2 | .17 | .42 | .43 | |||||||||

| ΔR2 | .17 | .26 | .01 | |||||||||

| F for ΔR2 | 21.04 | 95.02 | 6.63 | |||||||||

| AUDIT-dependence | ||||||||||||

| Age | −.32 | −6.93 | 0.09 | <.01 | −.15 | −3.65 | 0.02 | <.01 | −0.17 | −4.03 | 0.02 | <.01 |

| Gender a | .18 | 4.08 | 0.03 | <.01 | .11 | 2.92 | 0.01 | <.01 | .11 | 2.94 | 0.01 | <.01 |

| GCPS-CPI b | −.02 | −0.30 | <0.01 | .77 | −.04 | −.93 | <0.01 | .35 | −0.04 | −0.77 | <0.01 | .44 |

| GCPS-Dis c | .26 | 4.81 | 0.04 | <.01 | .09 | 1.89 | 0.01 | .06 | .10 | 2.00 | 0.01 | .05 |

| EAA d | .43 | 10.5 | 0.15 | <.01 | .21 | 2.25 | 0.01 | .03 | ||||

| DMS e | .23 | 5.41 | 0.04 | <.01 | .09 | 1.28 | <0.01 | .20 | ||||

| EAA × DMS | .31 | 2.79 | 0.01 | .01 | ||||||||

| R2 | .21 | .43 | .44 | |||||||||

| ΔR2 | .43 | .23 | .01 | |||||||||

| F for ΔR2 | 27.77 | 84.53 | 7.79 | |||||||||

| AUDIT-harms | ||||||||||||

| Age | −.26 | −5.45 | 0.06 | <.01 | −.09 | −2.10 | 0.01 | .04 | −0.09 | −2.00 | .01 | .05 |

| Gender a | .16 | 3.56 | 0.03 | <.01 | .29 | 2.28 | 0.01 | .02 | .09 | 2.28 | .01 | .02 |

| GCPS-CPI b | −.05 | −0.80 | <0.01 | .43 | −.08 | 1.56 | <0.01 | .12 | −0.08 | −1.59 | <0.01 | .11 |

| GCPS-Dis c | .27 | 4.78 | 0.05 | <.01 | .10 | 1.99 | 0.01 | .05 | .10 | 1.97 | .01 | .05 |

| EAA d | .45 | 10.4 | 0.16 | <.01 | .50 | 5.17 | 0.04 | <.01 | ||||

| DMSe | .22 | 4.94 | 0.03 | <.01 | .25 | 3.54 | 0.02 | <.01 | ||||

| EAA× DMS | −0.06 | −0.55 | <0.01 | .58 | ||||||||

| R2 | .16 | .39 | .39 | |||||||||

| ΔR2 | .16 | .23 | <.01 | |||||||||

| F for ΔR2 | 19.93 | 80.45 | .30 | |||||||||

- Note: β represents standardized Beta coefficient; Square root transformation was applied to AUDIT-Dependence and AUDIT-Harms scores; Bolded values indicate statistical significance (p < .05).

- a Male is coded as “0” and female is coded as “1”;

- b Graded Chronic Pain Scale – Characteristic Pain Intensity;

- c Graded Chronic Pain Scale – Disability Score;

- d Expectancies for Alcohol Analgesia Scale – Total Score;

- e Discrimination in Medical Settings – Total Score.

Expectancies for alcohol analgesia, medical discrimination, and alcohol dependence

Linear regression analyses indicated that the EAA score was positively associated with AUDIT-Dependence score and explained 15% of the unique variance in AUDIT-Dependence. DMS score was also positively associated with AUDIT-Dependence score, accounting for 4% of the unique variance in AUDIT-Dependence score. Moreover, there was a significant interaction between EAA score and DMS score on AUDIT-Dependence score (β = .31, p = .005; see Table 2). Conditional analyses revealed a positive association between EAA and AUDIT-Dependence at low (b = 0.021, SE = 0.004, p < .001), moderate (b = 0.026, SE = 0.003, p < .001), and high (b = 0.035, SE = 0.004, p < .001) levels of DMS score (see Figure 2).

Expectancies for alcohol analgesia, medical discrimination, and alcohol-related harms

Hierarchical linear regression analyses revealed that the EAA score was positively associated with AUDIT-Harms score and accounted for 16% of its unique variance. Likewise, DMS score was positively associated with AUDIT-Harms score, explaining 3% of the unique variance in AUDIT-Harms scores. DMS score did not significantly moderate associations between EAA score and AUDIT-Harms score (see Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Consistent with hypotheses, expectancies for alcohol analgesia were found to be positively associated with established indices of alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence and alcohol-related harms. Notably, expectancies for alcohol analgesia accounted for 15%–23% of the unique variance in alcohol consumption, dependence and alcohol-related harms, suggesting that military veterans with chronic pain who hold stronger beliefs that alcohol can help them reduce or manage pain may be at greater risk for hazardous drinking patterns. Results further indicated that discrimination in medical settings moderated associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and alcohol consumption and dependence. Specifically, relations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and alcohol consumption and dependence were stronger among veterans who reported greater discrimination in medical settings. One possible explanation for this finding stem from evidence that discrimination in medical settings is related to reduced healthcare utilization.20, 21 Indeed, prior experiences of discrimination in medical settings may increase the likelihood that veterans who hold beliefs that alcohol can reduce pain will attempt to self-medicate pain by drinking, rather than by seeking pain treatment. This is consistent with the self-medication hypothesis of addiction,31 which suggests that individuals are more likely to turn to alcohol use to alleviate distressing symptoms when other coping mechanisms are unavailable, unwanted, or perceived as ineffective. Ultimately, this may lead to the development and maintenance of hazardous patterns of alcohol use. Contrary to our expectations, discrimination in medical settings did not moderate associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and alcohol-related harms. Perhaps medical discrimination amplifies associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and constructs more central to alcohol use (i.e., quantity and/or frequency of drinking and physiological reliance on alcohol), rather than the drinking-related negative consequences, which tend to occur less frequently and depend more on situational factors, such as drinking environment or social context.32 Collectively, these findings broadly align with previous research among nonveteran samples5, 12-14 and extend this study by highlighting the role of discrimination in medical settings.

Results indicated that expectancies for alcohol analgesia were correlated with greater pain intensity and pain-related disability, consistent with previous work among nonveteran samples.12 Perhaps this is because individuals with more severe and disabling pain have more opportunities to experience the pain-relieving effects of alcohol, thus reinforcing their expectancies for alcohol analgesia. Conversely, linear regression results indicated that measures of pain severity were no longer associated with indices of alcohol consumption, dependence, or alcohol-related harms after accounting for expectancies for alcohol analgesia and discrimination in medical settings. It is possible that because chronic pain populations generally experience more elevated and prolonged pain, the expectancy that alcohol will relieve pain, therefore, contributes more strongly to drinking behaviors. Consistent with this perspective, previous work provides initial support for interventions challenging expectancies that smoking will reduce their pain.33 Future research should investigate the potential clinical utility of interventions targeting expectancies for alcohol analgesia. Furthermore, the current findings provide evidence that discrimination in medical settings warrants attention as a potential facilitator of hazardous alcohol use among veterans with chronic pain. Perhaps healthcare providers should be aware that veterans with chronic pain who have experienced discrimination in medical settings may be more likely to turn to alcohol for pain-coping—particularly if they hold beliefs about the utility of alcohol as an analgesic. More research is needed to develop and implement system-level interventions, including provider training and efforts to address structural bias, to reduce discrimination in medical settings. Such interventions may indirectly decrease hazardous drinking among patients with chronic pain who hold expectancies for alcohol analgesia.

Several important limitations should be noted. First, given the cross-sectional design, we cannot determine the directionality of observed associations. It is possible that heavier alcohol use could contribute to increased pain perception or to more frequent experiences of discrimination in medical settings. In addition, as is generally the case for alcohol outcome expectancies,10, 11 expectancies for alcohol analgesia and drinking behavior may be mutually reinforcing. Future research should use longitudinal designs to clarify the temporal relationships among discrimination in medical settings, pain, and hazardous drinking. Second, those who experience more discrimination in medical settings may also encounter more discrimination in other contexts. Given the previously observed associations between discriminatory experiences and both chronic pain34 and hazardous drinking patterns,17 it is possible that the current results are not unique to discrimination in medical contexts, and may extend to other forms of discrimination. Third, much like the U.S. veteran population, the current sample was predominantly white and male, and perceived reasons for discriminatory experiences in medical settings were not assessed. Individuals from diverse backgrounds or clinical populations (i.e., racial or ethnic minorities, women, or people with chronic pain) experience differing, and often intersecting, forms of discriminatory treatment in medical contexts.35 Future research should explore whether relations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia, discrimination in medical settings, and hazardous drinking vary among veterans from multiple or intersecting minoritized groups. Fourth, the current study did not assess mental health comorbidities, which are common in veteran populations and may confound the observed associations among discrimination, pain, and drinking. Future studies should include comprehensive measures of mental health conditions to clarify their role in these relationships. Fifth, this sample consists of U.S. veterans who completed an online survey and, therefore, may not reflect the experiences of veterans from vulnerable groups (i.e., veterans experiencing homelessness or with severe substance use disorders). Sixth, the present study did not explore potential targets of interventions which may reduce the degree to which discrimination in medical settings may amplify associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and hazardous drinking. Future research is warranted to inform interventions that reduce discrimination in medical settings, which may ultimately contribute to better patient outcomes, including reducing hazardous drinking among veterans with pain. Seventh, because the present sample was comprised of U.S. military veterans with chronic pain who drank alcohol in the past month, these findings cannot be generalized to non-veterans, non-drinkers, or individuals without pain.

In conclusion, this study is the first to identify discrimination in medical settings as moderating associations between expectancies for alcohol analgesia and indices of hazardous drinking among veterans with chronic pain. These findings highlight the importance of considering discrimination in healthcare contexts when examining risk factors for hazardous drinking in this population. Future research may support the clinical utility of interventions that address both alcohol analgesia expectancies and experiences of discrimination among veterans with pain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.