Case series: Symptom-inhibited fentanyl induction (SIFI) onto treatment-dose opioid agonist therapy in a community setting

Abstract

Background and Objectives

Existing opioid agonist therapy (OAT) guidelines are far from sufficient to address rising opioid tolerances and potency of the unregulated opioid market in North America. Inadequate starting doses of OAT are a universally recognized barrier for people who use fentanyl. Our objectives are to present a novel induction protocol called symptom-inhibiting fentanyl induction (SIFI) that uses rapid intravenous fentanyl administration to inhibit symptoms of opioid withdrawal.

Methods

We describe two cases highlighting the potential clinical utility of SIFI.

Results

This case series demonstrates two safe and successful transitions onto higher-than-standard doses of methadone and slow-release oral morphine harnessing an emerging approach of SIFI in a community clinic setting.

Discussion and Conclusions

These results support emerging evidence that SIFI is safe and feasible to meet patients' opioid requirements and facilitate rotation onto OAT. Further studies are needed to increase the generalizability of these findings.

Scientific Significance

Safe transitions onto treatment-dose OAT are of heightened clinical importance at a time when fentanyl and high-potency synthetic opioids are now the norm. SIFI is a novel induction method that could address significant gaps in the currently available OAT options in the fentanyl era.

BACKGROUND

Canada is in the midst of an unprecedented overdose crisis, with British Columbia (BC) being one of the most severely impacted. The most recent and pronounced wave of the overdose crisis has been driven in large part by fentanyl, a synthetic opioid with potency and lethality levels far higher than heroin.1 Between January 2023 and June 2024, fentanyl was detected in 85% of all unregulated drug deaths in BC.2

Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) is currently indicated as best practice for the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD).3 Growing evidence, however, suggests that the treatment trajectory of individuals who receive OAT may be compromised in the era of fentanyl. In BC, provincial guidelines for OUD recommend starting doses of 30–40 mg methadone and 300 mg slow-release oral morphine (SROM) for people who use fentanyl.4 However, anecdotal evidence has found fentanyl withdrawal to have a faster onset, higher severity, and longer duration than other opioids, driving users to prematurely exit treatment.5 Pharmacokinetic studies of fentanyl have suggested that the worsened withdrawal is likely due to its lipophilic accumulation in peripheral stores and long terminal elimination.6

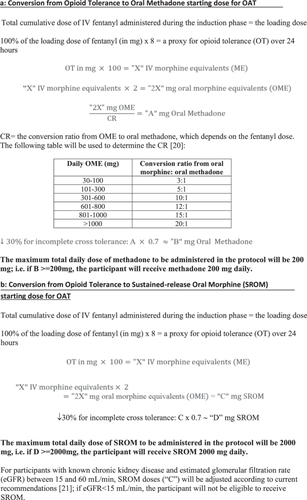

A novel alternative induction protocol uses rapid intravenous (IV) fentanyl administration to inhibit symptoms of opioid withdrawal (thus “symptom-inhibited fentanyl induction,” hereafter referred to as SIFI) and objectively determine opioid tolerance. This protocol has been described in a patient with severe OUD and unregulated fentanyl use to receive optimized doses of OAT and avoid withdrawal in an inpatient setting.7 In brief, once patients reach their subjective readiness threshold for induction, 400 mcg of IV fentanyl is administered with repeat doses every 5 min, with each dose followed by assessments of sedation, vital signs, withdrawal symptoms, cravings, and comfort levels. Once baseline safety is established through vital measurements, doses increase stepwise up to 800 and 1200 mcg until either subjective comfort or a Pasero Opioid-Induced Sedation Scale (POSS) score of two is obtained.8 Dose increases will occur after each time safety is established through the varied assessments. The patient is monitored for sedation levels and vital signs at 5, 10, and 15 min following the final dose, at which point induction is complete. The total cumulative dose of IV fentanyl administered from start to completion of SIFI is used as a measure of opioid tolerance, which in turn is used to calculate and transition patients to an equivalent starting dose of either methadone or SROM. Patients will receive maximum daily doses of up to 200 mg methadone or 2000 mg SROM (Figure 1). In this paper, we present two cases where SIFI has safely and successfully been completed in a community clinic with patients who use fentanyl. Written consent was obtained from both patients. The protocol and informed consent forms were approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board (H23-00111). The SIFI protocol is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05905367).

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

The patient is a 51-year-old male with severe OUD and 30 years of illicit opioid use. He has a lifelong history of trauma, chronic pain, unstable housing, and mental health challenges. His medical history includes concurrent nicotine use disorder, stimulant use disorder, and benzodiazepine use disorder. He self-reported smoking or injecting 7 gm fentanyl daily. He had previously been treated with buprenorphine-naloxone, extended-release buprenorphine, SROM, oral hydromorphone, IV diacetylmorphine, and fentanyl patches. His most recent OAT was 175 mg methadone, canceled due to missed doses. He received a 40 mg dose the day before his clinic visit.

Before SIFI, his Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS)9 score was two, and he was slightly tachycardic with a heart rate of 104 bpm. He reported smoking 0.1 g of fentanyl immediately before the clinic visit and having opioid cravings. His SIFI consisted of a total 9600 mcg of IV fentanyl administered over 79 min (Table 1a). Over induction, his COWS gradually dropped to zero and his POSS did not increase above one. Based on his opioid tolerance, his SROM dosing was calculated to be 538 mg. The patient was transitioned to 200 mg methadone, with the first dose administered in clinic with hourly assessments for 3 h thereafter. He received methadone at the clinic for a total of 8 days, with missed doses on Days 2 and 7. His COWS scores remained around 0 or 1 with the exception of a 3 on the 3rd day following a missed dose the day prior. Electrocardiogram (ECG) interval measurements were taken on Days 4 and 8, with QTc intervals of 425 and 392, respectively. One week after SIFI, his daily OAT prescription was increased to 205 mg of methadone per the client's request and transferred to a community pharmacy. No hospital admissions, naloxone administration, or emergency department visits were required during the induction or in the next 30 days. All measured indices, including heart rate and oxygen saturation levels, remained within normal ranges at follow-up visits including on Day 30. At Day 30, he remained stable on his methadone and verbally reported satisfaction with OAT.

| (a) Case 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission timeline | Fentanyl IV | Dose (mcg) | Cumulative fentanyl dose (mcg) | COWS | POSS | Methadone daily doses (mg) |

| Day 1 | 400–800 mcg q5 min prn (induction) | 400 | / | 2 | 1 | |

| 400 | / | 2 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 2 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 1 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 2 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 2 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 1 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 1 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 1 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 1 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 1 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 0 | 1 | |||

| 800 | 9600 | 1 | 1 | 200 | ||

| Day 2: no show | ||||||

| Day 3 | 3 | 1 | 200 | |||

| Day 4 | 0 | 1 | 200 | |||

| Day 5 | 1 | 1 | 200 | |||

| Day 6 | 1 | 1 | 200 | |||

| Day 7: no show | ||||||

| Day 8 | 3 | 1 | 200 | |||

| (b) Case 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | 400–800 mcg q5 min prn (induction) | 400 | / | 6 | 1 | |

| 400 | / | 5 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 6 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 4 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 4 | 1 | |||

| 800 | / | 4 | 1 | |||

| 800 | 4800 | 1 | 2 | 2000 | ||

| Day 2 | 2 | 1 | 2000 | |||

| Day 3 | 2 | 1 | 2000 | |||

| Day 4 | 1 | 1 | 2000 | |||

| Day 5 | 1 | 2 | 2000 | |||

| Day 6: no show | ||||||

| Day 7 | 3 | 1 | 2000 | |||

- Abbreviations: COWS, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Score; IV, intravenous; mcg, microgram; mg, milligram; POSS: Pasero Opioid-Induced Sedation Scale; prn, as needed; q_h, every hour(s); q_min, every minute(s).

Case 2

A 36-year-old female with a longstanding history of addiction and chronic pain presented to the clinic. In addition to her severe OUD, her comorbidities include hepatitis C virus infection, asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease, stimulant use disorder, tobacco use disorder, and two previous cerebral vascular accidents. Her illicit opioid use began 24 years previously and she self-reported smoking or injecting up to 1.75 g fentanyl daily. Due to negative experiences with side effects, the patient had remained on 50 mg of methadone for 2 years and was reluctant to increase her dose any further.

The patient's last reported use was smoking 0.05 g fentanyl and crystal methamphetamine immediately before the clinic visit. She had received her regular prescription of 50 mg methadone earlier in the day. During assessment, her baseline QTc interval was 413, POSS score was 1, and she tested negative for pregnancy. She was determined to be in a mild state of withdrawal with a COWS of six and symptoms of restlessness, join aches, nasal stuffiness, anxiety, sweating, and opioid cravings.

Her SIFI induction phase consisted of total 4800 mcg of IV fentanyl administered over 50 min, throughout which her withdrawal symptoms improved (Table 1b). Based on her opioid tolerance, her SROM dosing was calculated to be 5376 mg. Following SIFI, she was transitioned to 2000 mg of daily SROM. The first dose was administered in clinic, similar to all other doses following apart from Day 6. Her POSS scores consistently remained at 1 with the exception of a 2 on Day 5. Her COWS scores ranged from 1 to 2 and rose to a maximum of 3 on Day 7 following a missed dose on the day prior. Her subjective comfort levels and vital signs, including QTc interval, remained normal from the preinduction baseline throughout the induction week.

After 7 days, she continued to have strong cravings and withdrawal when using less illicit fentanyl. She requested a higher SROM dose and underwent a scheduled titration to 2500 mg. For 10 days thereafter, she did not encounter any complications or need for medical care. On Day 13, she reported feeling unwell with symptoms including diplopia. Following assessment, a diagnosis was made of neurosyphilis, unrelated to SIFI or OAT. Two months following the induction, she had completed antibiotic treatment, was stable and continuing to receive daily 2800 mg SROM.

DISCUSSION

This case series supports emerging evidence that SIFI is safe and feasible to meet patients' opioid requirements and facilitate rotation onto effective doses of OAT. To our knowledge, there have been no formal studies of IV fentanyl used as a means to transition to methadone or SROM in a community clinic setting. Though more research is needed, the potential implications of this are significant, from increasing the clinical utility of OAT to improving patient satisfaction and overall retention in a community setting.

Following its arrival and proliferation in North America, fentanyl has exponentially increased the number of lives lost to overdose. OAT initiations are a particular challenge for people who use fentanyl and whose opioid tolerance levels are far higher than can be immediately accommodated by current protocols.10 An analysis of 39,456 BC patients identified that methadone initiation in compliance with current guidelines was associated with an increased risk of death or hospitalization within the next 6 months.11 The adaptation of novel induction protocols for people who use fentanyl, including more rapid methadone titration, has been recommended by recent guidelines12 and described in several case reports.13-15 A recent retrospective chart review of hospitalized OUD patients also demonstrated safety with up-titrating methadone doses quicker than with traditional induction.16 This work is critical to pursue in an era when fentanyl is omnipresent. Pragmatic approaches like SIFI are needed to reduce the risks of mortality from fentanyl overdose and OAT discontinuation.

CONCLUSION

In the wake of the ever-growing overdose crisis, there is an urgent need to innovate OAT to ensure adequacy for those who use fentanyl. Strategies that are both desirable and acceptable to the growing population of fentanyl users are a necessity for treatment systems to keep up with the evolving toxic street drug supply. This case series demonstrates a novel approach and application of SIFI that can meet the needs of the patients where they are, prevent fatal and nonfatal overdose in those who exit treatment, and improve their engagement with the care system.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.