The impact of audit quality in rights offerings

Abstract

Using audit quality as our core focus, we take a fresh look at the tradability and standby status in rights offerings, and the market reaction during the subscription period in the US market. We find that firms with high audit quality are more likely to choose tradable or full standby rights issues. We also find that the subscription period price reaction is positively related to audit quality and negatively related to issue price discount. These results demonstrate an important role played by the choice of auditors in the design of rights offerings, particularly in mitigating the negative price reaction during the subscription period.

1 Introduction

Prior studies have suggested that audit quality plays an important role in costly financing decisions. For example, Titman and Trueman (1986) demonstrate that a firm with more favourable private information about its value chooses a higher quality auditor and investment banker than a firm with less favourable private information. Mansi et al. (2004) show that firms employing Big N auditors enjoy a lower cost of debt. Khurana and Raman (2004) show that a Big 4 audit is associated with a lower ex ante cost of equity capital in the US. Chang et al. (2009) argue that auditor quality is quite critical to the success of corporate financing decisions as auditors play an important assurance role regarding the integrity of financial statements and show that companies audited by Big 6 firms (compared to those audited by small audit firms) are more likely to issue equity as opposed to debt. Moreover, Chang et al. (2009) suggest that while the theoretical literature has suggested that Big 6 auditors serve a valuable function, there is a paucity of empirical evidence on the importance of auditor quality to companies’ financing decisions.

Accordingly, we extend the audit quality literature, represented by the signature work of Titman and Trueman (1986) and Chang et al. (2009), to examine the role of audit quality in the context of right offering decisions. More specifically, we focus on the association between audit quality and transferability and standby features in the design of rights offerings, and the market reaction during the rights offering period. As rights offerings are widely used internationally, the evidence in this paper contributes to further understanding of the importance of audit quality on firms financing decisions around the world.1

In rights offerings, existing shareholders receive short-term warrants to purchase newly issued shares on a pro rata basis at a discount relative to the current market price of the stock. Firms can issue rights with either a tradable or non-tradable option, as well as employing an underwriter to certify (fully, partially or uninsured) their rights offerings.2 All existing shareholders are given the chance to participate, so that there is no dilutive effect to those who choose to exercise the rights offered to them. Although rights offerings have been used as one choice of financing method around the globe, there are practical differences across countries. One notable example of such differences is whether shareholder approval is required. Rights offerings are the predominant SEO method in Australia, and the Australian Securities Exchange requires shareholder approval of any stock issuance greater than 15 percent of existing capital that is not offered pro rata to all shareholders. In contrast, rights offerings are less frequently used in the US, where managers can issue shares in public offerings without shareholder approval.

Our first analysis centres on the tradability feature of rights offerings. Using an Australian sample, Balachandran et al. (2008) show that high quality firms signal their own quality by selecting renounceable rights (known as ‘transferable’ rights offerings in the US) and employ an underwriter to fully certify the issue (known as ‘full standby’ rights in US) in raising new capital using rights offerings. However, Ursel (2006) examines the transferable rights offerings in the US and shows that firms in financial distress with difficulty accessing underwriting services use rights offerings. Using an international sample of rights offerings, Massa et al. (2016) argue that firms seem to restrict rights trading to raise financing when the prospect of restructuring is more doubtful and the need to force the hand of the existing shareholders is higher. They suggest that firms with poor expected future performance may issue non-tradable rights offerings to ‘coerce existing investors to bail out the firm’.

Holderness and Pontiff (2016) find that as compared with tradable offerings of US firms, non-tradable offerings are associated with lower shareholder participation, greater wealth transfers, and a more unfavourable market reaction, while investment bankers are reluctant to underwrite rights offerings because the long duration of the subscription period forces them to bear too much risk. The authors conclude that agency conflicts influence the use of rights offers in the US. However, neither they nor other prior studies specify what kind of agency problems investors/market participants infer from tradable versus non-tradable rights offerings. Based on this discussion, we argue that firms with higher audit quality have more transparent and reliable accounting information, thus the transaction costs of trading rights and of preparing a more elaborate prospectus should be smaller. As such, our first hypothesis proposes that firms with high audit quality are more likely to choose tradable rights offerings.

Our second analysis focuses on the standby feature of rights offerings. Balachandran et al. (2012) show that Australian firms with higher liquidity use fully underwritten rights offerings while, in contrast, Kothare (1997) shows that rights offerings in the US impose a significant indirect cost on issuers by reducing the liquidity of the issuer's stock. In a recent study, Holderness and Pontiff (2016) find that shareholder participation in rights offerings of US firms is considerably lower than previously asserted, which causes wealth transfers from non-participating to participating shareholders that average 7 percent of the offerings.3 They suggest that shareholder non-participation may help explain the puzzling paucity of rights offerings in the US. Eckbo and Masulis (1992) and Eckbo (2009) argue that a major cost of non-participation in rights offerings arises due to ‘adverse selection’ where markets with ‘hidden information’ sellers have at least the potential to know more than buyers about the true value of the item being sold. Singh (1997) contends that the adverse selection component is inversely related to the proportion of the rights issue taken up by current stockholders and, hence, higher take-up levels should be associated with relatively more favourable information.

Given that firms using rights offerings to raise capital in the US face financial distress (Ursel, 2006), the lack of shareholder participation and investment banker involvement to underwrite in rights offerings (Holderness and Pontiff, 2016), we argue that high audit quality reduces the information asymmetry between informed managers, underwriters and existing shareholders. Hence, with those rights offerings linked to higher audit quality, underwriters might not demand higher investigation costs and the transaction costs of preparing a more elaborate prospectus should be smaller. Therefore, we propose our second hypothesis that firms with high audit quality are more likely to secure underwriter certification for their rights offerings.

Our final analysis examines how the market perceives the quality features of rights offerings. Heinkel and Schwartz (1986) demonstrate that there is information content in the choice of financing method and if a rights issue fails, the terminal stock price will be less than the subscription price at the rights issue expiration date. Balachandran et al. (2012) examine the insights of the Heinkel and Schwartz (1986) prediction by investigating the market reaction during the subscription period for Australian right offerings and find that the market reacts negatively during the subscription period. The market reacts more negatively to uninsured rights offerings compared to full standby rights offerings, more favourably for firms with a higher shareholder take-up and more unfavourably for firms with a larger subscription price discount. Still, there is a scarcity of research examining the impact of shareholder take-up on the price reaction during the subscription period in the US or, indeed, in any other market setting. Our study helps redress this situation.4 We also argue that investors have lower (higher) confidence in the financial statements of firms with lower (higher) audit quality, and such firms will experience significant (less) negative effects on their stock price following rights offering announcements. We therefore propose our final hypothesis that firms with high audit quality will experience a less unfavourable price reaction during the subscription period.

As the rights offering method is a predominant form of seasoned equity offerings (SEOs) around the world, we extend this strand of research by examining the role of audit quality in determining tradability and standby status in rights offerings and in mitigating the negative price reaction during the subscription period. Auditor quality may be endogenous, and some firm characteristics, such as size, may drive the results related to audit quality (see, e.g., Chang et al., 2009; Lawrence et al., 2011; Lennox et al., 2012).5 We follow Chang et al. (2009) to use two strategies to address endogeneity. In the first approach, the predicted Big N auditor is included as an explanatory variable in the ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions. We use Big N auditors at the balance sheet dates immediately prior to the rights offering announcement and firm variables that are lagged 2 years to estimate the predicted Big N auditor. In the second strategy, instrumental variable (IV) regressions are performed in which we use the predicted value of the Big N auditor as an instrument (Wooldridge, 2002). We use 500 bootstrap iterations to obtain 95 percent confidence intervals.

Using a sample of 168 rights offerings for the period from 1980 to 2013, we find support for the three hypotheses outlined above. First, firms with Big N auditors are more likely to make tradable rights offerings.6 Second, firms with Big N auditors tend to choose full standby issues. Third, the subscription period price reaction is positively related to Big N auditor. Overall, we find that firms with higher audit quality tend to issue tradable rights and employ an underwriter to fully certify the issue and mitigate negative price reaction during the subscription period.

We make two core contributions to the literature. First, we contribute in the broad area of rights offerings. Balachandran et al. (2008) show that larger firms with higher leverage, lower idiosyncratic risk, higher ownership and higher shareholder take-up tend to issue tradable rights, and larger and older firms making tradable rights employ underwriters to fully certify the issue. Balachandran et al. (2012) find that firms with higher liquidity issue fully underwritten rights offerings and that firms with lower shareholder participation experience larger negative price reactions during the subscription period. Balachandran et al. (2017) examine the issuance choice across rights issues of equity, unit offerings and standalone warrants, and find that agency costs, growth opportunities and current funding needs relative to assets in place are prime drivers of the type of equity issuance choice. Holderness and Pontiff (2016) find that non-tradable rights offerings are associated with a more negative stock price reaction and greater wealth transfers from the non-participating shareholders to the others. Adding to this strand of the literature, we propose audit quality as an important factor that influences the design features of tradability and standby of rights offerings and mitigates the negative price reaction during the subscription period. In a related study, Lee and Masulis (2009) find that low accrual quality is associated with higher flotation costs, larger negative SEO announcement effects, and a higher probability of SEO withdrawals. Pushing further in this broad direction, our study uses audit quality as a proxy for accounting quality and shows that audit quality has a strong linkage with design features of rights offerings.

Second, we contribute to the literature built around the role of audit quality on financing decisions. Prior studies document that audit quality affects the cost of equity in IPOs (Willenborg, 1999; Copley and Douthett, 2002); the cost of debt (Mansi et al., 2004); debt-monitoring costs (Pittman and Fortin, 2004); the choice of debt versus equity financing (Chang et al., 2009). However, there is little known about the effect of auditor quality on the features of rights offerings. Our study shows that audit quality plays an important role in the design features of rights offerings as well as in the market reaction to rights offering announcements.

Our paper proceeds as follows. Section 22 presents a brief literature review and hypothesis development. This is followed by discussion of the research design in Section 33. We then examine the factors that affect (i) the choice of tradable rights, and (ii) the choice of full standby versus partial standby vis-à-vis uninsured rights in Section 44. Section 55 presents the empirical results on price reaction. The final section concludes.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

Our study draws on two strands of the literature. The first strand studies the role of audit quality in financing decisions. The second examines the quality features of rights offerings. First, according to Jensen and Meckling (1976), credible financial reporting could reduce information asymmetry between managers and other stakeholders, improve investor confidence, raise the stock price and thereby make it less costly for firms to raise new equity capital. This in turn gives rise to management demands for creditable financial reports. Put differently, managers have stronger incentives to use auditing services, which provide independent assurance of the credibility of financial reporting information (DeFond and Zhang, 2014). The audit literature has documented that high audit quality increases the credibility of financial reporting (Skinner and Srinivasan, 2012; DeFond and Zhang, 2014). Becker et al. (1998) show that clients of non-Big Six auditors report discretionary accruals that are, on average, 1.5–2.1 percent of total assets higher than the discretionary accruals reported by clients of Big Six auditors.

Titman and Trueman (1986) develop a model and demonstrate how the quality of the chosen auditor can rationally be used by investors in valuing new issues. Mansi et al. (2004) argue that the potential conflicts of interests among owners, managers and other security holders create an environment in which an outside auditor can contribute significant value to investors and show that firms employing Big N auditors enjoy a lower cost of debt. Pittman and Fortin (2004) examine the impact of auditor choice on debt pricing in firms’ early public years when they are lesser known and show that by retaining a Big Six auditor, a firm can reduce debt-monitoring costs by enhancing the credibility of financial statements. Khurana and Raman (2004) show that a Big 4 audit is associated with a lower ex ante cost of equity capital for auditees in the US. Chang et al. (2009) argue that auditor quality is quite critical to the success of corporate financing decisions because auditors play an important assurance role regarding the integrity of financial statements and in reducing information asymmetry. They show that companies audited by Big 6 firms compared to those audited by small audit firms are more likely to issue equity rather than debt. However, this strand of the literature remains silent on whether audit quality has any significant effect on rights offerings, a major form of SEO financing by modern corporations.

If rights issues are tradable and if shareholders do not want to take up their rights, then they can sell them in the market. Balachandran et al. (2008) argue that if companies believe that they have a market for rights and expect that some shareholders would not participate in the take-up, they can use renounceable (instead of non-renounceable) issues to provide an opportunity for non-participating shareholders to sell their rights. They find that Australian firms offering tradable rights issues have higher shareholder participation than firms offering non-tradable rights issues. Massa et al. (2016) argue that firms seem to restrict rights trading in order to raise financing when the prospect of restructuring is more doubtful and the need to force the hand of existing shareholders is higher. Holderness and Pontiff (2016) show that non-transferable rights offerings are associated with greater wealth transfers and a more negative stock-price reaction. They argue that market participants, therefore, could reasonably infer agency problems given that management does not take a simple step that in most instances it could take and would benefit many shareholders – namely, to make the offer transferable. However, neither they nor other prior studies specify what kind of agency problems investors/market participants infer from tradable versus non-tradable rights offering.

We argue that firms with higher audit quality have more transparent and reliable accounting information; thus, the transaction costs of trading rights and of preparing a more elaborate prospectus should be smaller. As such, firms with high audit quality are more likely to choose tradable rights offerings. We propose our first hypothesis as follows:

- H1 Firms with high audit quality will issue tradable rights offerings.

One attribute of rights offerings is whether issuing firms can secure an underwriter to certify their issues. Balachandran et al. (2008) argue that low quality firms, from a signalling cost–benefit perspective, are unwilling/unable to pay the investigation costs to fully underwrite a rights issue because investigation costs are likely to be (too) high for low quality firms and/or the underwriter might not be willing to undertake the insurance of all shares in the issue due to the high idiosyncratic risk. Moreover, managers of these firms are likely to lack confidence in their ability to issue uninsured rights due to a concern about poor take-up from shareholders. Ursel (2006) finds that firms suffering financial distress issue uninsured rights in the US. She argues that these firms have little to lose from the costs of adverse selection that accompany the lack of underwriter certification. Lee and Masulis (2009) argue that poor accounting quality is related to higher information asymmetry and raises uncertainty about a firm's financial condition for outside investors. This, in turn, lowers demand for a firm's new equity, raise underwriting costs.

In the spirit of these studies, we argue that firms with high audit quality have more transparent and reliable accounting information; as such, underwriters will not demand higher investigational costs and, therefore, these firms can more readily secure underwriter certification for their rights offerings. Accordingly, we predict that firms with higher audit quality will be able to make full standby rights offerings. Thus, we formally propose the following hypothesis:

- H2 Firms with high audit quality will choose full standby rights offerings.

Smith (1977) argues that if the shareholder does not exercise his rights, or does not sell his rights to someone who will exercise the rights, his wealth is reduced by the market value of the rights. Consequently, the firm can make the probability of failure of the rights offering arbitrarily small by setting the subscription price sufficiently low. According to Singh (1997), underwriters have incentives to target a lower subscription price to make the rights offer viable. Moreover, from this perspective, underwriters will set the subscription price and underwriting fees consistent with the perceived risk attaching to the offer process for each given firm. Heinkel and Schwartz (1986) argue that there is information content in the choice of financing method and if a rights issue fails, the terminal stock price will be less than the subscription price at the rights issue expiration date. Balachandran et al. (2012) examine the Heinkel and Schwartz (1986) prediction by investigating the market reaction during the subscription period and find that the market reacts more favourably to rights offerings with high quality features, e.g., full standby issues and issues with higher shareholder take-up, and more unfavourably to issues with larger subscription price discounts.

We argue that investors have lower (higher) confidence in the financial statements of firms with lower (higher) audit quality, and such firms will experience significant (less) negative effects on their stock price following rights offering announcements. The resultant hypothesis is then:

- H3 Firms with high audit quality will experience a less unfavourable price reaction during the subscription period.

3 Research design

3.1 Data and sample

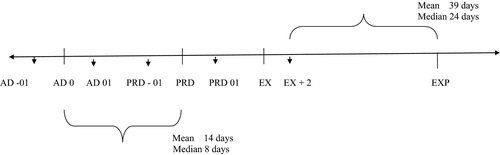

We identify US firms that conduct rights offerings during the period 1980–2013. Data regarding rights offering announcements are gathered from four main sources: Thomson One Banker (SDC Module), Bloomberg, Factiva and the SEC Edgar database. We also search the Internet for company press releases announcing rights offerings. On average, there are 14 trading days between the first public announcement of the offer and the price release date (see Figure 1).

Initially, we obtain a sample of 302 rights issues. We exclude 76 firms because they lack SEC filings data. We drop a further 58 events with incomplete return data and subscription price, duplicate issuance, those issues which are units, preference shares, warrants, and issues that are terminated. The final sample consists of 168 distinct events. Details of sample exclusions are provided in Table 1. Our sample compares favourably with other US studies (see, e.g., Eckbo and Masulis, 1992; Kothare, 1997; Singh, 1997; Holderness and Pontiff, 2016). We also obtain actual shareholder take-up for 161 announcements from the news releases issued at the conclusion of the rights offerings from Factiva.7 For standby rights offerings, the majority of companies disclose separate figures for the take-up by existing shareholders versus standby purchasers. From the SEC Edgar database, searching the proxy document ‘DEF 14 A’, we hand collect audit fee data and beneficial ownership (sum of the shareholding across all substantial (5 percent and above) holdings for a given firm), at the balance sheet date immediately prior to each rights offering announcement.

| Panel A: Data filtering | |

|---|---|

| Reason for sample exclusion | No of offerings |

| Initial sample of US firms before exclusions | 302 |

| Less exclusions | |

| SEC filings unavailable | 76 |

| Return series data unavailable | 18 |

| Units offerings | 8 |

| Preference stock offerings | 15 |

| Warrants | 7 |

| Restructuring offerings | 4 |

| Debenture offerings | 6 |

| Total exclusions | 134 |

| Final sample | 168 |

| Panel B: Summary of the sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Big 6 auditor | Non Big 6 auditor | Total | |

| Transferable versus non-transferable | |||

| Tradable | 53 | 11 | 64 |

| Non-tradable | 49 | 55 | 104 |

| Total | 102 | 66 | 168 |

| Fully standby versus partial standby versus uninsured offering | |||

| Fully standby | 22 | 8 | 30 |

| Partial standby | 12 | 14 | 26 |

| Uninsured standby | 68 | 44 | 112 |

| Total | 102 | 66 | 168 |

We retrieve the following information from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP): daily return and market return data for each company from 1 year prior to the announcement date to the subscription expiration date, daily bid ask price and market capitalisation 1 month prior to the announcement date. We collect firm annual accounting data (at the balance sheet date immediately prior to the issue announcement) from Compustat. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the financial characteristics of our sample firms for Big 6 versus non-Big 6 auditors separately. As can be seen in this table, larger firms with higher leverage, ownership concentration and liquidity use Big 6 auditors. Firms with Big 6 auditors tend to raise more funds than firms with non-Big 6 auditors. In untabulated results, we find that 83 percent of tradable rights offerings were made by firms with Big 6 auditors, 73 percent of the full standby rights offerings were made by firms with Big 6 auditors, 46 percent of partial standby rights offerings were made by firms with Big 6 auditors, and 61 percent of non-underwritten rights offerings were made by firms with Big 6 auditors.

| Big 6 auditor | Non-Big 6 auditor | MW test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MV ($m) | |||

| Mean | 477.56 | 93.05 | 3.95*** |

| Median | 114.03 | 37.57 | |

| BM | |||

| Mean | 0.88 | 0.92 | 1.25 |

| Median | 0.96 | 1.00 | |

| OP ($m) | |||

| Mean | 116.99 | 34.14 | 4.73 |

| Median | 38.60 | 10.00 | |

| TDRATIO | |||

| Mean (%) | 37.06 | 20.82 | 4.07*** |

| Median (%) | 31.00 | 11.50 | |

| OPTOMV | |||

| Mean (%) | 53.26 | 55.33 | 0.69 |

| Median (%) | 31.00 | 28.00 | |

| BENOWN | |||

| Mean (%) | 46.81 | 38.80 | 2.06** |

| Median (%) | 46.00 | 33.00 | |

| TA ($m) | |||

| Mean | 1,720.93 | 709.71 | 2.30** |

| Median | 386.78 | 181.35 | |

| AGE | |||

| Mean | 11.71 | 15.94 | 2.80*** |

| Median | 8.95 | 14.26 | |

| DISC | |||

| Mean (%) | 19.17 | 21.70 | 0.57 |

| Median (%) | 16.00 | 18.00 | |

| EBITDATA | |||

| Mean (%) | −3.04 | −1.02 | 1.05 |

| Median (%) | 1.50 | 1.00 | |

| RUNUP | |||

| Mean (%) | 5.97 | 11.52 | 0.75 |

| Median (%) | −10.50 | 4.00 | |

| PBA1YR | |||

| Mean (%) | 4.48 | 6.40 | 2.05** |

| Median (%) | 3.00 | 4.00 | |

| IDYRISK | |||

| Mean | 4.94 | 5.01 | 0.06 |

| Median | 4.00 | 4.00 | |

| Sample size | 102 | 66 | |

- This table provides financial characteristics of our sample, partitioning on Big 6 auditors versus non-Big 6 auditors. The table also provides nonparametric test statistics Mann-Whitney (MW)/t-test for the differences in median/mean values between two sub groups; and Kruskal-Wallis test (KW)/ANOVA-test for the differences in median (mean) values between three sub-groups. Details of variable definitions are in Appendix I. *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

3.2 Audit quality variables

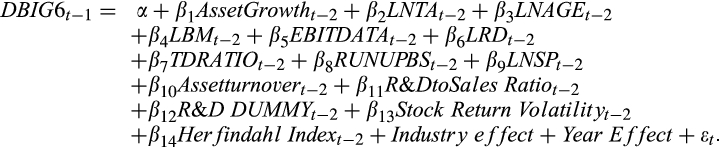

(1)

(1)In this regression, the dependent variable is DBIG6, which takes a value of unity if a firm chooses a Big 6 auditor and 0 otherwise. Following Chang et al. (2009), we use Big 6 auditors at the balance sheet dates immediately prior to the rights offering announcement and estimate a probit regression model based on the firm variables that are lagged 2 years. We use 500 bootstrap iterations to obtain 95 percent confidence intervals.

The set of control variables comprise a wide range of firm characteristics employed by previous studies in the auditor quality selection model. In line with Willenborg (1999), we use firm size (LNTA: natural logarithm of total assets); median stock price (LNSP: natural logarithm of median monthly closing prices over a 12-month period); asset turnover (sales divided by total assets); and asset growth (change in log of total assets). Following Weber and Willenborg (2003), we also use the Herfindahl index (computed by the sum of the squared market shares within each three-digit SIC industry); R&D to Sales Ratio (R&D divided by sales); and a dummy variable equal to 1 if R&D expenses are missing (R&D DUMMY) and 0 otherwise. We also use a dummy variable for litigation industry (LRD: litigation risk dummy) as a measure of litigation risk (see Hogan, 1997; Krishnan and Krishnan, 1997). We follow Chang et al. (2009) and use the leverage ratio (the ratio of the total debt to total assets) and stock return volatility (standard deviation of monthly return for the financial year) as determinants of audit quality. We expect that high growth and more profitable firms tend to hire big auditors. We employ LBM as an inverse proxy for growth opportunities and EBITDATA (EBITDA divided by total assets) as a measure for profitability. As mature firms usually have larger market share than younger firms, they are more likely to hire top audit firms. Furthermore, firms experiencing lower price run-up also tend to hire Big 6 audit firms. Accordingly, we use RUNUPBS (return over the 12-month period prior to the balance sheet date) and firm age (LNAGE: natural logarithm of age, where age of the firm is measured in years since the firm entered the Compustat database) as determinants of audit quality.

To estimate the predicted Big 6 auditor, we use all firms with more than $1 million assets from the Compustat database during the period 1980–2013. Due to our limited sample size, unlike Chang et al. (2009), we do not restrict our sample to those firms with 5-year data available in Compustat or to industrial firms. We follow Lennox et al. (2012) by imposing several exclusion restrictions in the second stage regression. Specifically, we include several variables in the first stage regressions because prior literature on audit quality suggests that they are determinants of auditor choice. Specifically, those variables are as follows: firm age (LNAGE); asset turnover (Asset Turnover); asset growth (Asset Growth; Willenborg, 1999); Herfindahl index (Herfindahl Index; Weber and Willenborg, 2003); closing stock price (LNSP); whether a firm discloses R&D expenditure (R&D DUMMY); R&D intensity (R&D to Sales Ratio); and litigation risk (LRD; Hogan, 1997). Previous studies (e.g., Chang et al., 2009) document that larger companies with higher asset turnover, higher stock price, higher return on assets (ROA), lower litigation risk, lower volatility and lower growth are more likely to be audited by Big 6 audit firms. However, these variables are excluded from the second stage regressions because the literature on rights offerings does not suggest that those variables are significant determinants of transferability or standby status in rights offerings (e.g., Balachandran et al., 2008; Holderness and Pontiff, 2016).

3.3 Sample selection bias – determinants of the likelihood of using rights offerings

We address sample selection bias arising from the choice of rights offerings by employing a probit regression on the issuance choice between rights versus other cash offerings, following the well-known 2-stage Heckman solution. Specifically, in stage 1, we model the likelihood of firms using rights offerings and obtain the inverse Mills ratio (IMR), while in stage 2, we include IMR as an additional explanatory variable in our main model. The results for the stage 1 probit regression are reported in Panel B of Table 3.

| Panel A: Determinants of the likelihood of Big 6 auditor | Panel B: Determinants of the likelihood of issuing rights offerings | |

|---|---|---|

| Asset Growth | −0.08 | −0.44 |

| (−9.21)*** | (−4.71)*** | |

| LNTA | 0.14 | −0.08 |

| (49.42)*** | (−4.43)*** | |

| LNAGE | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| (6.02)*** | (1.91)* | |

| LBM | −0.30 | 0.71 |

| (−34.60)*** | (7.48)*** | |

| EBITDATA | 0.59 | 0.15 |

| (24.06)*** | (1.13) | |

| LRD | −0.44 | 0.23 |

| (−56.88)*** | (3.13)*** | |

| TDRATIO | 0.38 | 0.46 |

| (19.84)*** | (3.22)*** | |

| RUNUPBS | −0.16 | |

| (−22.89)*** | ||

| LNSP | 0.10 | |

| (19.94)*** | ||

| Asset turnover | 0.18 | |

| (30.86)*** | ||

| R&D to Sales Ratio | 0.69 | |

| (33.55)*** | ||

| R&D DUMMY | −0.47 | |

| (−56.54)*** | ||

| Stock Return Volatility | 0.84 | |

| (15.92)*** | ||

| Herfindahl Index | 0.56 | |

| (17.69)*** | ||

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Sample size | 160,923 | 8,538 |

- Panel A of this table presents the results for modelling the likelihood of the company selecting a Big 6 auditor, as a proxy for high audit quality. The dependent variable is the DBIG6, which equals 1 if a firm chooses a Big 6 auditor and 0 otherwise. Panel B presents the results for modelling the likelihood of the company choosing to make a rights offerings. The dependent variable is the DRIGHTS, which equals 1 if a firm chooses rights offerings and 0 otherwise. Details of variable definitions are in Appendix I. The z-statistics in parentheses are calculated from Huber/White/sandwich heteroscedastic consistent errors. *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

4 Results and discussions

4.1 Audit quality and tradability features of rights offerings

(2)

(2)| (1) | |

|---|---|

| EBIG6 | 2.30** |

| (2.29) | |

| ROA | −0.63 |

| (−0.90) | |

| Z-score | 0.02 |

| (0.49) | |

| OPTOTA | 0.31 |

| (1.06) | |

| TDRATIO | 1.04** |

| (2.54) | |

| LBM | 1.32*** |

| (3.01) | |

| RUNUP | 0.27* |

| (1.82) | |

| LNPBA1YR | −0.15 |

| (−1.46) | |

| BENOWN | 0.08 |

| (0.18) | |

| LNTA | −0.04 |

| (−0.38) | |

| IDYRISK | −6.91* |

| (−1.77) | |

| IMR | 5.37 |

| (1.46) | |

| Constant | −5.99** |

| (−2.14) | |

| Observations | 168 |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.23 |

- This table reports the probit regression results regarding the effects of audit quality on the decision to issue tradable rights using EBIG6 as audit quality proxy. The dependent variable is DTRAD, which equals 1 for tradable rights and 0 otherwise. Details of variable definitions are in Appendix I. *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 4 reports the results relating to the decision to issue tradable rights using the predicted Big 6 auditor (EBIG6) as a proxy for audit quality. We find that the estimated coefficient on the expected Big 6 auditor variable (EBIG6) has the expected positive sign, statistically significant at the 5 percent level. As such, this finding suggests that high audit quality firms are more likely to choose tradability in their rights issues, supporting H1.8

In terms of the role of the control variables, we make the following brief observations. Firms making tradable rights offerings also tend to have higher leverage. We further find that firms that issue tradable rights on average have lower idiosyncratic risk and higher liquidity. Tradable rights issuers tend be ‘value’ firms (i.e. firms with higher book to market value). The estimated coefficients on beneficial ownership and firm size are statistically insignificant, indicating that these variables have little influence on the issuance choice between tradable versus non-tradable rights offerings. The estimated coefficients on OPTOTA and RUNUP are statistically insignificant.

Since firms choosing non-tradable offerings tend to be smaller, have higher leverage and lower profitability (Massa et al., 2016), these firms are also more likely to hire non-Big N firms. Therefore, it is possible that audit quality does not affect the tradability decision of rights offerings, but rather that certain covariates affect firms’ choice over auditors as well as their design of rights offerings. To address this ‘omitted variables’ concern, we also conduct the nearest neighbour propensity score matching (PSM) and re-examine whether audit quality affects the tradability feature of rights. Specifically, we estimate the probability of being assigned to a treatment or a control firm using a logit regression where the dependent variable (DTRAD) is a dummy variable, which equals 1 for transferable rights (treatment firms) and 0 for non-transferable rights (control firms). The control variables are all firm-level control variables in Equation 2) except BIG6 because we want to remove some differences in the other covariates, rather than BIG6, that may affect the tradability feature in this matching procedure. After this PSM procedure, the matching sample has 64 transferable rights and 64 non-transferable rights. When comparing mean differences in the covariates of treatment firms with those of control firms both before and after matching, we find that the matching has achieved its purpose. Specifically, it is only the difference in BIG6 between transferable rights and non-transferable rights that remains significant. Notably, when we re-estimate the effect of BIG6 on the choice of transferable rights issues using this matching sample, we find that the coefficient estimate on BIG6 is positive and still significant (albeit at the 10 percent level), suggesting that our results remain robust to this matching approach. We present these results in Appendix II.

4.2 Audit quality and standby features of rights offerings

In this section, we examine the impact of audit quality on the issuance choice of full standby versus partial standby and uninsured rights offerings versus partial standby (relating to H2). To this end, we estimate a multinomial logistic regression model where the dependent variable is the offering choice which takes a value of 0 for a partial standby (i.e. base case), a value of 1 for uninsured rights, and a value of 2 for a full standby rights offering. Again, we use the predicted Big 6 auditor variable (EBIG6) as a proxy for audit quality. We bootstrap this system 500 times to obtain consistent standard errors. Similar to the above, to mitigate the sample selection bias arising from the choice of rights offerings versus other cash offerings, we include IMR as a control variable in all models. Since firm size, relative issue size, idiosyncratic risk and liquidity are highly correlated, we use various other specifications. We present the results in Table 5.

| UN | FS | |

|---|---|---|

| EBIG6 | −0.07 | 6.63** |

| (−0.04) | (2.27) | |

| ROA | 1.96 | 2.51 |

| (1.64) | (1.07) | |

| Z-score | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| (−1.13) | (−0.45) | |

| OPTOTA | −0.15 | 0.23 |

| (−0.28) | (0.27) | |

| TDRATIO | 3.23** | 1.70 |

| (2.22) | (1.09) | |

| LBM | −0.66 | −1.70* |

| (−0.87) | (−1.73) | |

| RUNUP | 0.18 | 0.41 |

| (0.50) | (0.98) | |

| LNPBA1YR | −0.17 | −0.18 |

| (−0.66) | (−0.65) | |

| BENOWN | 0.66 | 1.60 |

| (0.58) | (1.23) | |

| LNTA | −0.01 | 0.40* |

| (−0.04) | (1.94) | |

| IDYRISK | −10.06 | −22.89** |

| (−1.21) | (−2.12) | |

| IMR | −25.83** | −32.63** |

| (−2.56) | (−2.44) | |

| Constant | 20.08*** | 16.53* |

| (2.59) | (1.68) | |

| Observations | 168 | |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.29 | |

- This table presents the effects of audit quality on the issuance choice of full standby, partial standby and uninsured rights offerings using a multinominal logistic regression model, with EBIG6 as a proxy for audit quality. The dependent variable is the offering choice, which equals 0 for uninsured rights (UN), 1 for partial standby (PS), and 2 for full standby (FS). The reported results use PS as the base outcome. Details of variable definitions are in Appendix I. *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 5 show that the estimated coefficient on the expected Big 6 auditor variable (EBIG6) has the expected positive sign and is statistically significant at the 5 percent level for fully standby rights.9 These results indicate that high audit quality firms choose full standby rights, which supports H2. We also find that the estimated coefficient on EBIG6 is not statistically significant for the choice of uninsured issues over partial standby, thus indicating that auditor quality does not appear to play any role in determining uninsured versus partial standby issues.10

4.3 Robustness check: impact of audit fees on tradability and standby decisions

Behn et al. (1999) argue that the audit firm may perform a high quality audit in the hope of enhancing client satisfaction, which in turn can increase the amount the client is willing to pay for the audit. Willenborg (1999) argues that the existence of an information signalling demand for auditing implies that a higher quality audit should command a price premium and the audit fee should contain an implicit insurance premium. Carcello et al. (2002) contend that in the case where firms demand higher audit assurance, audit fees will be higher because more work is required. Francis (2004) argues that the higher audit fee implies higher audit quality either through greater auditor expertise or through more auditor effort. Caramanis and Lennox (2008) argue that audit firms are less motivated if they are being underpaid and therefore deliver less effort in performing their audit duties. Accordingly, as a robustness check, in this section, we test the determinants of the decision to issue tradable and standby rights using audit fees as an alternative proxy for audit quality.

Similar to the previous analysis, we employ expected audit fee (ELAUDFEE) as a proxy for audit fees. Specifically, ELAUDFEE is the modelled ‘expected’ value of LAUDFEE, analogous to the creation of EBIG6 above. LAUDFEE is the natural logarithm of audit fees (in $m) at the balance sheet date immediately prior to the announcement. Specifically, we hand collect audit fees for the year prior to the announcement of rights offerings for 131 observations during the period 1980–2013 and estimate the following regression (due to data availability, N = 131):

| LAUDFEE = | −3.46 | + | 0.29 × LNTA | + | 0.81 × DBIG6 | + |

| (−12.42)*** | (7.11)*** | (4.40)*** | ||||

| 5.67 × IDYRISK | R 2 | |||||

| (2.80)** | 0.39 |

Audit fee is positively related with firm size (LNTA), Big 6 auditor dummy (DBIG6), and idiosyncratic risk (IDYRISK). Based on fitted values, the predicted audit fee from this model (ELAUDFEE) is used as the key independent variable in the second stage analysis.

Panel A of Table 6 presents the regression results regarding the effect of audit fees on the decision to issue tradable rights. In Model 1, we omit LNTA, IDYRISK and Big 6 auditor as independent variables as they are used to predict ELAUDFEE for our sub-sample of 131 audit fee observations. The estimated coefficient on ELAUDFEE has the expected positive sign and is statistically significant, indicating that firms paying higher audit fees choose tradable rights. This finding reinforces the earlier finding that audit quality plays a positive role in determining the tradable rights decision.

| Panel A: Audit fee and tradable rights | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| ELAUDFEE | 0.39** | |

| (2.20) | ||

| ELAUDFEEYE | 0.21* | |

| (1.93) | ||

| OPTOTA | 0.245 | 0.20 |

| (0.99) | (0.81) | |

| TDRATIO | 0.97** | 1.13*** |

| (2.38) | (2.91) | |

| LBM | 0.77** | 0.91*** |

| (2.27) | (2.63) | |

| RUNUP | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| (1.30) | (1.25) | |

| LNPBA1YR | −0.20** | −0.21** |

| (−2.32) | (−2.48) | |

| BENOWN | 0.19 | 0.28 |

| (0.47) | (0.66) | |

| IMR | 4.07 | 5.33 |

| (1.11) | (1.53) | |

| Constant | −5.10* | −5.20* |

| (−1.86) | (−1.89) | |

| Observations | 168 | 168 |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Panel B: Audit fee and standby status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |||

| UN | FS | UN | FS | |

| ELAUDFEE | −0.12 | 0.61* | ||

| (−0.38) | (1.75) | |||

| ELAUDFEFYE | −0.19 | 0.58** | ||

| (−0.86) | (2.15) | |||

| LAUDFEE | ||||

| IMR | 24.31** | 10.98 | −23.10** | −17.33 |

| (2.44) | (1.07) | (−2.45) | (−1.40) | |

| OPTOTA | 0.10 | −0.90 | −0.17 | −1.28 |

| (0.18) | (−1.08) | (−0.33) | (−1.35) | |

| TDRATIO | −2.75** | −1.09 | 3.11** | 1.81 |

| (−1.99) | (−1.08) | (2.05) | (1.13) | |

| LBM | 0.49 | −1.03 | −0.19 | −1.36 |

| (0.78) | (−1.16) | (−0.31) | (−1.40) | |

| RUNUP | −0.14 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| (−0.48) | (0.36) | (0.43) | (0.42) | |

| LNPBA1YR | 0.32 | −0.18 | −0.31 | −0.52** |

| (1.38) | (−0.95) | (−1.38) | (−1.99) | |

| BENOWN | −0.58 | 1.19 | 0.57 | 2.08 |

| (−0.54) | (1.43) | (0.53) | (1.63) | |

| Constant | 16.59** | 9.97 | ||

| (2.31) | (1.06) | |||

| Observations | 168 | 168 | ||

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.20 | 0.24 | ||

- This table provides the regression results on the impact of audit fees on tradability and standby features of rights offerings. Panel A reports the probit regression results for tradable rights where the dependent variable (DTRAD) equals 1 for tradable rights and 0 otherwise. Panel B presents the multinomial regression results for standby status of rights offerings. The dependent variable in Panel B is the offering choice, which equals 0 for uninsured rights (UN), 1 for partial standby (PS), and 2 for full standby (FS). The reported results use PS as the base outcome. Details of variable definitions are in Appendix I. *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

Given that our sample period is 33 years in length, we re-estimate the LAUDFEE equation using year fixed effects and use the predicted value of LAUDFEE (ELAUDFEEYE) from this case, as an alternative proxy for audit quality. This alternative analysis is reported in Model 2 in Panel A of Table 6. We find that the coefficient of ELAUDFEEYE is significantly positive, confirming support for H1. In addition, we use actual LAUDFEE as another alternative proxy for audit quality in Model 3, and find that the estimated coefficient on LAUDFEE is significant and positively related to the tradability decision. In sum, the results presented in this panel suggest that when using audit fees as a proxy for audit quality, we secure confirmatory support for H1.

Panel B of Table 6 presents the regression results regarding the effect of audit quality on the standby decision. We use ELAUDFEE (ELAUDFEEYE) as the audit quality proxy in Model 1 (Model 2). We find that the estimated coefficient on ELAUDFEE (ELAUDFEEYE) is positive and statistically significant at the 10 percent (5 percent) level, indicating that firms with higher audit quality tend to choose full standby over other issue methods.11 Overall, our analysis supports our key prediction that firms with higher audit quality tend to choose tradable and full standby rights offerings.

5 Testing the H3 price reaction

5.1 Univariate results

We employ a standard event study framework to examine the impact of rights offering announcements on share prices: (i) around the announcement period (AD − 1 to AD + 1); (ii) around the price release date (PRD −1 to PRD +1); and (iii) during the subscription period (EX + 2 to EXP). The market model is used to estimate abnormal returns with an estimation period spanning 260 days prior to the announcement day to 61 days before the announcement day. We use a standardised residual test statistic to identify the significance levels of the price reaction.

In Table 7, we report abnormal returns for the full sample, as well as a two-way sort based on tradability (Panel A), and a three-way sort based on standby status (Panel B). Several features are worthy of note. First, for the full sample, the average abnormal return (−2.83 percent) is significantly negative at the 5 percent level for the 3-day announcement period. We find that the average 3-day market reaction around the price release date is −4.44 percent, which is strongly and significantly negative at the 1 percent level. We also observe that the average market reaction over the subscription period is −8.32 percent and strongly significant at the 1 percent level for the full sample of rights offerings.

| Panel A: Tradable and non-tradable rights offerings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Window | All (1) | Non-tradable (2) | Tradable (3) | t-test |

| AD −1 to AD 1 | ||||

| Mean (%) | −2.83 | −3.22 | −2.19 | −1.60 |

| Median (%) | −1.48 | −1.88 | −0.96 | |

| SRT | (−2.11)** | (−2.64)** | (−1.75)* | |

| PRD −1 to PRD 1 | ||||

| Mean (%) | −4.44 | −5.57 | −2.60 | −1.73* |

| Median (%) | −3.10 | −3.76 | −2.26 | |

| SRT | (−6.96)*** | (−6.70)*** | (−2.73)*** | |

| EX +2 to EXP | ||||

| Mean (%) | −8.32 | −10.52 | −4.75 | −1.70* |

| Median (%) | −6.00 | −8.16 | −4.38 | |

| SRT | (−1.63)* | (−1.80)* | (−3.79)*** | |

| Sample | 168 | 104 | 64 | |

| Panel B: Uninsured rights, partial standby and full standby rights offerings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Uninsured (1) |

Partial standby (2) |

Full standby (3) |

ANOVA (1,2,3) |

t-test (1) vs. (3) |

t-test (2) vs. (3) |

t-test (1) vs. (2) |

|

| AD −1 to AD 1 | |||||||

| Mean (%) | −3.39 | −3.16 | −0.42 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.04 | 0.11 |

| Median (%) | −1.59 | −2.12 | −0.25 | ||||

| SRT | (−3.11)*** | (−1.67)* | (−2.20)** | ||||

| PRD −1 to PRD 1 | |||||||

| Mean (%) | −4.50 | −6.73 | −2.24 | 1.20 | 0.99 | 1.75* | 0.92 |

| Median (%) | −2.87 | −6.35 | −1.61 | ||||

| SRT | (−5.36)*** | (−3.95)*** | (−2.42)*** | ||||

| EX +2 to EXP | |||||||

| Mean (%) | −10.64 | −12.95 | 4.33 | 7.01*** | 3.57*** | 3.22*** | 0.50 |

| Median (%) | −7.22 | −10.00 | 1.03 | ||||

| SRT | (−1.92)* | (−1.11) | (1.87)* | ||||

| Sample | 112 | 26 | 30 | ||||

- This table reports mean and median abnormal returns and the standardised residual t-tests (SRT) employing the market model for rights-issue announcements for the period 1 day before the announcement to the day after the announcement (AD −1 to AD 1), the period day before the price release date to the day after (PRD −1 to PRD 1); and 2 days after the expiration date to the subscription expiration day (EX +2 to EXP). Panel A reports price reaction results for tradable versus non-tradable issues. Panel B presents the results based on standby status. We use standardised residual t-test to report whether average abnormal return is significantly different from zero. This table also provides t-test and ANOVA statistics for the difference in mean abnormal returns across the different groupings. *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

To identify the differential market impact relating to tradability, we compare the average abnormal returns between the tradable and non-tradable subgroups. The average market reactions for the 3-day announcement period for both categories are significantly negative, which are −3.22 percent for non-tradable rights and −2.19 percent for tradable offerings. The announcement period reactions are not significantly different between non-tradable and tradable rights. We also find that the market reactions over the price release period are significantly negative for both non-tradable rights offerings (−5.57 percent) and tradable offerings (−2.60 percent). Panel A also shows that the price reaction during the subscription period is significantly negative for both the non-tradable and tradable offerings with −10.52 percent and −4.75 percent, respectively. Moreover, the market reaction is significantly more negative for non-tradable rights than tradable rights at the 10 percent level for both the price release and subscription periods.

We also report the differential market impact to the announcement of standby status in Panel B of Table 7. We find that the average market reactions around the initial announcement date are significantly negative for uninsured offerings (−3.39 percent), partial standby (−3.16 percent) and full standby offerings (−0.42 percent). However, while the negative price reactions seem to vary across groups, they are not statistically significantly different from each other (pairwise or all three together). We find that the average market reactions over the price release period are significantly negative for uninsured offerings (−4.50 percent), partial standby (−6.73 percent) and full standby offerings (−2.24 percent). However, they are not statistically significantly different from each other except the full versus the partial standby at the 10 percent level. During the subscription period, the market reacts positively to full standby issues (4.33 percent), negatively to partial standby (−12.95 percent) and uninsured issues (−10.64 percent). The market reactions for the subscription period are significantly different across all combinations at the 1 percent level except the one between partial standby and uninsured issues.

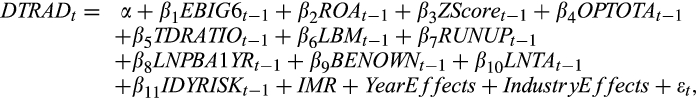

5.2 Cross-sectional regression analysis

In this section, we analyse the factors that determine the subscription period abnormal returns and, in particular, the impact of audit quality on subscription period reaction, the focus of H3.12 We regress abnormal stock returns during the subscription period on audit quality together with other relevant variables DISC, TAKEUP, RUNUP, TDRATIO, BENOWN, OPTOTA, IDYRISK, LNTA, LNPBA1YR and IMR. We bootstrap this system 500 times to obtain consistent standard errors. We present the results in Table 8.

| (1) | |

|---|---|

| EBIG6 | 0.18* |

| (1.82) | |

| TDRATIO | −0.08 |

| (−1.51) | |

| LNTA | −0.01 |

| (−0.93) | |

| OPTOTA | 0.00 |

| (0.07) | |

| LNPBA1YR | −0.03** |

| (−2.15) | |

| IDYRISK | −0.21 |

| (−0.38) | |

| RUNUP | −0.03* |

| (−1.67) | |

| BENOWN | 0.08 |

| (1.49) | |

| DISC | −0.50*** |

| (−3.95) | |

| TAKEUP | 0.08 |

| (1.19) | |

| IMR | −0.90** |

| (−2.26) | |

| Constant | 0.39 |

| (1.32) | |

| Observations | 161 |

| R 2 | 0.45 |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes |

- This table provides cross-sectional regression results explaining the market response to rights-offering announcements during the subscription period. The dependent variable is the price reaction during the subscription period. Details of variable definitions are in Appendix I. *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 8 shows that the estimated coefficient on EBIG6 has the expected positive sign and is statistically significant at least at the 10 percent level, which supports H3. This finding indicates that firms with high auditor quality experience more favourable price reactions during the subscription period.13

As for control variables, we find that the subscription discount has a negative coefficient that is significant at least at the 1 percent level, which is consistent with the findings of Balachandran et al. (2012). The RUNUP coefficient takes the expected negative sign and is statistically significant. This RUNUP finding indicates that there is a tendency for companies which experience major stock price appreciations (declines) in the year prior to the rights issue, to suffer a decline (increase) in value over the subscription period. The relative issue size (OPTOTA) is insignificant. The firm size (LNTA) is also insignificant in all models. The estimated coefficient on LNPBA1YR is significantly negative, indicating that high liquidity firms experience less unfavourable price reactions during the subscription period. The estimated coefficient on TAKEUP is insignificant. This finding contradicts Balachandran et al. (2012), who report that the extent of take-up by shareholders has a significantly (very strong) positive impact on the subscription period price reaction.

6 Conclusion

We examine the role of audit quality on the determinants of tradability and standby status in rights offerings and on the market reaction during the subscription period. We find new evidence that audit quality has a significant influence over the design features of rights offerings. We also find that the subscription period price reaction is positively related to audit quality. Our findings are consistent across various approaches that are designed to mitigate the bias due to the endogeneity between audit quality and issuance choice decisions. Overall, our findings highlight the importance of audit quality in the design features of rights offerings in the US.

Since rights offerings are less common in the US, it will be interesting to examine whether audit quality plays a similar role in an international setting using a larger sample. Though prior research examines the impact of audit quality in non-US settings around various corporate events (see e.g., Zhu et al. (2015) around mergers; Lee (2016) around IPOs; Xu et al. (2017) around private placements), the role of audit quality in rights offerings in such non-US settings is largely unexplored. In particular, we recommend further research examining the impact of audit quality on the design features of rights offering in countries such as Australia and the UK, which regularly use rights issues.

Notes

Appendix I A: Variable definitions

| Variable name | Definition |

|---|---|

| AGE | The age of the firm in years since the firm entered Compustat |

| Asset Growth | Change in the log of total assets |

| Asset Turnover | Sales divided by total assets |

| AUDFEE | Audit fees in $m at the balance sheet date immediately prior to the announcement |

| BENOWN | The proportion of shares owned by beneficial owners |

| BM | Total assets/(Total assets − book value of equity + market value of equity) |

| DBIG6 | A dummy variable, which equals 1 for a Big 6 audit firm and 0 for other firms |

| EBIG6 | The modelled ‘expected’ value of DBIG6, employing a probit regression using Big 6 auditor data at the balance sheet immediately prior to the announcement of rights offerings as a dependent variable and the other variables related to Big 6 auditor at the balance sheet immediately 2 years prior to the announcement of rights offerings |

| DFS | A dummy variable, which equals 1 for a full standby issue and 0 otherwise |

| DISC | The subscription price discount measured as (1 − Sc/Pt − 2), where Pt − 2 is the share price 2 days prior to the rights issue price release date and Sc is the subscription (issue) price for the new shares under the rights issue |

| DPS | A dummy variable, which equals 1 for a partial standby issue and 0 otherwise |

| DTRAD | A dummy variable, which equals 1 for a tradable rights issue and 0 for a non-tradable rights issue |

| DUNINS | A dummy variable, which equals 1 for an uninsured standby issue, and 0 otherwise |

| EBITDATA | The ratio of earnings before interest, tax and depreciation to total assets |

| ELAUDFEE | The modelled ‘expected’ value of LAUDFEE, employing a probit regression using audit fee data at the balance sheet immediately prior to the announcement of rights offerings, not using year fixed effect |

| ELAUDFEEFY | The modelled ‘expected’ value of LAUDFEE, employing a probit regression using audit fee data at the balance sheet immediately prior to the announcement of rights offerings using year fixed effect |

| Herfindahl Index | Sum of the squared market shares within each three-digit SIC industry |

| IDYRISK | A proxy for idiosyncratic risk calculated as the standard error of the market model regression for the 1-year period prior to the announcement date (return from day −260 to day −2) |

| IMR | Inverse Mills ratio from a stage 1 regression modelling the likelihood of using rights offerings |

| LBM | Logarithm of book-to-market ratio |

| LMV | Logarithm of the market value 1 month prior to the rights issue announcement |

| LNUDFEE | Logarithm of audit fees at the balance sheet date immediately prior to the announcement |

| LNAGE | Logarithm of age where age of the firm is measured in years since the firm entered Compustat |

| LNPBA1YR | Logarithm of average proportionate bid ask spread for 1-year period prior to the announcement of rights offering |

| LNSP | Logarithm of median monthly closing prices over a 12-month period |

| LNTA | Logarithm of total assets |

| LRD | Litigation risk industry dummy, which takes a value of unity if the firm is in a high litigation industry, and 0 otherwise |

| MMEXP2EXP | Price reaction for the period 2 days after the expiration date to the subscription period end date |

| MV | The market value of the company 1 month prior to the announcement |

| OP | The rights issue size measured by offering size |

| OPTOTA | Offer proceeds relative to total assets |

| PBA1YR | Average proportionate bid and ask spread for 1-year period prior to the announcement date |

| R&D to Sales Ratio | R&D divided by sales |

| R&D DUMMY | A dummy variable, which takes a value of 1 if R&D expenses are missing and 0 otherwise |

| ROA | The ratio of net income before extraordinary items to total assets (IB/AT) |

| RUNUP | Raw return over the period from day −260 to day −2 relative to the announcement date |

| RUNUPBS | Return over the 12-month period prior to the balance sheet date |

| Stock Return Volatility | Standard deviation of monthly return calculated for each firm each year |

| TA | Total assets at the balance sheet date |

| TAKEUP | The percentage of the rights issue taken up by existing shareholders. We obtain this data from the news releases issued at the conclusion of the rights offerings from Factiva |

| TDRATIO | The ratio of total debt to total assets |

| Z Score | Altman (1968) Z–score |

Appendix II B: Propensity score matching results for tradable versus non-tradable rights

| Panel A: Mean differences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before matching | After matching | |||||

| Tradable rights | Non-tradable rights | t-test | Tradable rights | Non-tradable rights | t-test | |

| (1) | (2) | (1) vs. (2) | (3) | (4) | (3) vs. (4) | |

| EBIG6 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 3.67*** | 0.71 | 0.61 | 2.38** |

| BIG6 | 0.82 | 0.47 | 4.89*** | 0.82 | 0.68 | 1.86* |

| ROA (%) | 1.97 | −6.97 | 2.23** | 1.97 | −2.04 | 1.32 |

| Z-score | 0.81 | 0.71 | 2.45** | 0.81 | 0.61 | 1.50 |

| OPTOTA | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.62 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.90 |

| TDRATIO (%) | 40.34 | 24.7 | 3.31*** | 40.34 | 34.52 | 1.52 |

| BM | 0.96 | 0.85 | 2.07** | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.62 |

| RUNUP | 0.02 | 0.10 | 2.01** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.62 |

| PBA1YR (%) | 4.20 | 5.80 | 2.57** | 4.20 | 4.45 | 1.60 |

| BENOWN (%) | 46.23 | 42.12 | 2.47** | 46.23 | 46.21 | 0.02 |

| LNTA | 6.23 | 5.30 | 3.15*** | 6.23 | 5.77 | 1.57 |

| TA | 2,055.34 | 873.33 | 2.60** | 2,055.34 | 1,109.91 | 1.65 |

| IDYRISK | 0.04 | 0.05 | 2.40** | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.06 |

| Sample | 64 | 104 | 64 | 64 | ||

| Panel B: The effect of BIG6 on tradability features | |

|---|---|

| BIG6 | 0.58* |

| (1.86) | |

| ROA | −0.81 |

| (−0.77) | |

| Z-score | 0.02 |

| (0.8) | |

| OPTOTA | 0.06 |

| (0.20) | |

| TDRATIO | 0.78* |

| (1.67) | |

| LBM | 0.54 |

| −1.38 | |

| RUNUP | 0.22 |

| (1.27) | |

| LNPBA1YR | −0.06 |

| (−0.56) | |

| BENOWN | 0.07 |

| (0.02) | |

| LNTA | 0.02 |

| (−0.30) | |

| IDYRISK | −6.61* |

| (−1.76) | |

| Constant | −1.58 |

| (−0.61) | |

| Observations | 128 |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.22 |

- This table presents the results of the effect of BIG6 on the choice of tradable versus non-tradable rights using the propensity score matching sample. Panel A compares the mean differences in the covariates of treatment firms (tradable rights) with those of control firms (non-tradable rights) for the sample before matching (columns (1) and (2)) and for the sample after matching (columns (3) and (4)). Panel B reports the logit regression results. The dependent variable is a dummy variable (DTRAD). Details of variable definitions are in Appendix I. *, ** and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.