The discrete and differential impact of monetary policy

The author would like to thank Katherine Uylangco, Paul Docherty, Steve Easton, Barry Oliver and the participants at the Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand (AFAANZ) and the Australasian Finance & Banking Conference for their valuable comments.

Please address correspondence to Bronwyn McCredie via email: [email protected]

Abstract

This study exploits a unique feature of the Australian monetary policy environment to determine whether economic recovery can be stimulated via central bank communications. This study finds that unexpected monetary policy announcements and communications have a significant and comparable impact on the value and volatility of the Australian foreign exchange market, suggesting that they can be used interchangeably to stimulate economic recovery. However, further analysis reveals that the state of the economy influences this impact. Specifically, during poor economic states, monetary policy actions speak louder than words, an adage that in this context provides actionable information for central bank regulators.

1 Introduction

The goal of monetary policy in Australia is to encourage strong and sustainable growth in the economy. This is traditionally achieved through central bank actions, that is, setting the target interest rate on overnight loans in the money market which influences the investment behaviour of firms and households, cash flows, credit, asset prices and the exchange rate. Recently, however, due to a stagnated and historically low cash rate,1 market participants are calling for forward guidance (Castelnuovo et al., 2018), for the Reserve Bank to be clearer about current conditions and those that could lead to a rate change to stimulate economic recovery. This call is based on the belief that Australia's economic recovery is possible through the provision of information, via central bank communications rather than actions, as rate cutting is no longer a viable option.2 Consequently, this study examines the discrete and differential impact of monetary policy actions and communications in the Australian foreign exchange market, a second stage channel of monetary policy,3 to determine the reach and reliability of this proposed course of action.

The Australian monetary policy environment is an ideal jurisdiction to examine this proposal because of the inability to directly observe the discrete impact of monetary policy actions and communications in US and European jurisdictions due to the timing of these events. For example, the announcement of the US Federal Funds rate by the Federal Open Market Committee is followed within 90 minutes by the release of so-called Projections Materials. Similarly, the European Central Bank announces its rate decision and 45 minutes later releases a statement pertaining to its position on monetary policy.

In Australia, these events occur 2 weeks apart, with the announcement of the monthly target interbank cash rate preceding the release of the minutes of the Reserve Bank board meeting that explicate the rate outcome. This study exploits this feature of the Australian monetary policy environment to examine first, the discrete and differential impact of monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases on the Australian foreign exchange market to determine the reach of central bank communications, and second, monetary policy impact subject to different economic states to determine its reliability.

Extant international (Guraynak et al., 2005) and Australian (Kearns and Manners, 2006)4 studies that examine the reach of monetary policy in the foreign exchange market have sought to disentangle the joint impact of the announcement and accompanying explanatory statements by employing a two-factor regression model. The first factor, proxied by the daily change of 1-month interest rates or 30-day futures contracts, is used to examine the impact of monetary policy announcements, whilst the second factor, proxied by the daily change of 3-month interest rates or 90-day futures contracts, is used to examine the impact of explanatory statements.5 These studies report that the joint impact of the monetary policy announcement and accompanying explanatory statements is greater on the 3-month proxy, suggesting that monetary policy statements have a much larger impact on financial instruments. However, the methodology employed in these studies is tortuous, as demonstrated by Neuenkirch (2013), who cites the importance of examining the communication of central banks independent of their announcements.6 To determine the reach of monetary policy, this study adopts a direct approach.

A wide literature also documents the need to control for the state of the economy when examining the impact of macroeconomic announcements on financial returns to determine policy reliability. For example, McQueen and Roley (1993) show that allowing for different stages of the business cycle influences the impact of macroeconomic announcements on the US stock market. Similarly, Jensen et al. (1996) and Anderson et al. (2003, 2007) demonstrate that the monetary environment (restrictive or expansive) and the state of the economy, respectively, affect the response of US bond and stock returns to macroeconomic news. Consequently, this study considers the possibility that different economic states may influence the impact of monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases on the Australian foreign exchange market. Previous studies by Zettlemeyer (2004) and Pennings et al. (2015) find that the effectiveness of monetary policy announcements did not differ during crisis periods, but their use of daily data7 and measures of expectation based on spot interest rates8 indicate a possible and documented limitation of their results. These studies also do not examine central bank communications or multiple measures for economic states, including consumer sentiment.

The use of consumer sentiment as an economic state variable is advocated in a recent study by Akhtar et al. (2011), which examined the impact of the Melbourne Institute's consumer sentiment index announcement on the Australian foreign exchange market. This impact was reported to be asymmetric with a significant depreciation of the AUD9 on days when negative sentiment is announced, but no comparable appreciation when positive sentiment is announced. Akhtar et al. (2011) argue that this asymmetry is due to the negativity effect, a theory originating in psychology (Cannon, 1932) which asserts that ‘bad’ news elicits a stronger response than ‘good’ news, due to our genetic predisposition (Baumeister et al., 2001).10 Further, Loundes and Scutella (2000) propose that consumer sentiment is a macroeconomic indicator. They demonstrate that consumer sentiment is a ‘useful indicator of total (private) consumption’ (p. 14) and a dominant factor in the calculation of gross domestic product (GDP), and therefore suggest that consumer sentiment may be used to forecast changes in economic growth or the business cycle. Taken together, these theories suggest that the impact of macroeconomic announcements on the Australian foreign exchange market (including monetary policy) will be influenced by consumer sentiment.

This study finds that unexpected monetary policy announcements and the release of explanatory minutes have a significant impact on the value and volatility of the Australian foreign exchange market. Contrary to extant literature (Guraynak et al., 2005; Kearns and Manners, 2006), when the relative impact of these surprises is examined, no discernible difference is found, suggesting that monetary policy actions and communications can be used interchangeably to stimulate the economy. Further, this study provides new evidence that the state of the economy influences the Australian foreign exchange market response to monetary policy. Specifically, the impact of unexpected monetary policy announcements (explanatory minutes’ releases) strengthens (is negated) in poor economic states. These results suggest that central bank actions, not communications, are required to stimulate economic recovery in poor economic states.

2 Data and research design

2.1 Data

Monetary policy announcement data were obtained from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) from January 199611 to December 2015. This is currently released at 14.30 hours on the first Tuesday of the month (excluding January when the board does not meet), following the RBA's monthly board meeting, regardless of whether the cash rate changes.12 Consequently, the sample consists of 220 monetary policy announcements: 52 occasions when the target interbank cash rate was changed (24 rate increases and 28 rate decreases) and 168 occasions where no change was recorded.

Information pertaining to the release of the explanatory minutes of the monthly RBA board meeting was also obtained from the RBA from December 2007 to December 2015. Since December 2007, these minutes have been released 2 weeks after the RBA board meeting (i.e. the third Tuesday of the month except January) and are held under embargo until 11.30 hours. To facilitate a meaningful announcement at this time, the RBA holds a media lock-up beginning at 10.30 hours. This gives the media the opportunity to review the minutes and prepare a statement for public release. The sample consists of 89 explanatory minutes’ releases.

Intraday data for the Australian/US dollar pairing (one of the most actively traded currency pairings in the world13), the 30-day cash rate and 90-day bank bill futures contracts were obtained from SIRCA's Thomson Reuters Tick History database.14 These data are recorded on a tick by tick basis.

Consistent with Smales (2015), consumer sentiment data for the Australian economy were obtained from the Melbourne Institute. These data are collected and reported monthly15 and represent the aggregate responses of consumers’ views regarding current and future economic conditions and household financial position.

2.2 Modelling the impact of unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases

2.2.1 Impact on the AUD/USD exchange rate

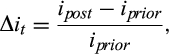

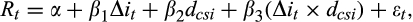

(1)

(1)The AUD/USD exchange rate is determined by averaging the last contributed bid and ask price each minute. Percentage changes in the AUD/USD exchange rate are calculated using 10-min time periods. This use of aggregated data is consistent with Kearns and Manners (2006) and is advocated by Danielsson and Payne (2002) who assert that quote data sampled every 5–10 min form suitable proxies for traded prices. Further, to ensure the timeliness and accuracy of the data, stale exchange rates are screened by cross-referencing price and volume data. Consequently, quoted bid and ask price observations with no recorded volume are deemed invalid and excluded from the sample. The remaining observations constitute the screened sample.18

The calculation of the information content of the explanatory minutes’ release differs from the monetary policy announcement, as the following month's contract (the second contract) in the 30-day cash rate futures is used instead of the current month's contract. The second contract was used due to liquidity issues as, once the RBA releases the monthly target interbank cash rate (on the first Tuesday of the month), trading in the current contract is virtually and sometimes literally non-existent.

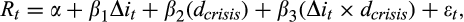

2.2.2 Relative impact of unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases

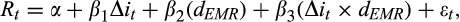

(2)

(2)2.2.3 Impact on the volatility of the AUD/USD exchange rate

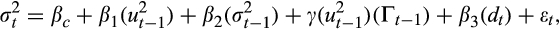

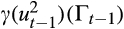

To study and compare the volatility response of the Australian foreign exchange market to unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases, a Threshold GARCH (TGARCH) model using a Student t distribution is employed.21 This model by Glosten et al. (1993) and Zakoian (1994) is frequently employed in studies of monetary policy (Lu et al., 2009; Smales, 2012). This is due to its ability to not only report on the magnitude and persistence of the impact of unexpected monetary policy announcements (explanatory minutes’ releases) on volatility, but also on any extant asymmetry between positive and negative news.

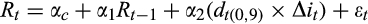

(3a)

(3a) (3b)

(3b)The interaction term (dt(0,9) × Δit) indicates the magnitude of the mean response to unexpected announcements/releases, and the dummy variable dt indicates the timing of the volatility response. The significance and coefficient of the GARCH term (β2) indicates the presence and degree of persistence, respectively. Further, the differential impact of positive and negative news from unexpected announcements/releases is identified by (β1) and (γ). Specifically, a significant coefficient on (β1) indicates the impact of positive news, and significant coefficients on (β1) + (γ) indicate the impact of negative news. Therefore, if (γ) is significant the volatility response is asymmetric.22

2.3 Economic states

To determine whether the state of the economy affects the reliability of monetary policy, by influencing the impact of unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases on financial returns, this study partitions the sample into crisis and non-crisis periods and separately, high and low sentiment periods. These dichotomous samples calculate the percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate (Rt) using 10-min intervals (t0,9–t−10,−1) to enable the clear detection of any variation.

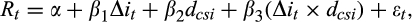

2.3.1 Global financial crisis

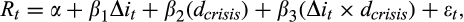

(4)

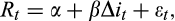

(4)2.3.2 Sentiment

(5)

(5)Heteroscedasticity is controlled for in all OLS regressions by employing the White test and outliers are trimmed from the data by excluding any return in the surprise variables (the 30-day cash rate and 90-day bank bill futures contracts) greater than three standard deviations from the mean.24

3 Results

This section is divided into two parts. First, the impact or reach of unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases on the Australian foreign exchange market is reported. Secondly, this study determines whether policy reliability is affected by economic conditioning based on the GFC and consumer sentiment.

3.1 Impact on the AUD/USD exchange rate

3.1.1 Monetary policy announcements

The results from estimating the impact of monetary policy announcements on the Australian foreign exchange market are provided in Table 1. Using both the 30-day cash rate and the 90-day bank bill futures contracts to calculate the unexpected component of the monetary policy announcement, an immediate (within 10 min) response is documented. Specifically, using changes in the 30-day cash rate (90-day bank bill) futures contract as a proxy for surprise, this study demonstrates that an unexpected 100 basis point increase in the target interbank cash rate leads to an instantaneous appreciation of the Australian dollar by 0.174 percent (0.149 percent). This result is significant at the 1 percent level. As the RBA generally increases or decreases the cash rate in 25 basis point increments, this result may be contextualised as an unexpected 25 basis point tightening leading to an instantaneous 0.044 percent (0.037 percent) appreciation of the Australian dollar.

| Time to announcement | 30-day cash rate | 90-day bank bill | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | T-statistic | Coefficient | T-statistic | |

| −10, −1 | 0.000 | −0.01 | 0.011 | 1.21 |

| 0,9 | 0.174 | 5.76** | 0.149 | 5.03** |

| 10,19 | 0.010 | 1.31 | 0.014 | 1.63 |

| 20,29 | 0.006 | 0.65 | 0.008 | 0.97 |

| 30,39 | −0.003 | −0.47 | 0.006 | 0.65 |

| 40,49 | −0.001 | −0.12 | −0.003 | −0.41 |

| 50,59 | 0.005 | 0.86 | 0.007 | 1.01 |

| n | 131 | 199 | ||

- Results reported are derived from the model: where Rt represents the percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate using 10-min intervals from t−10 to t60 and Δit represents the unexpected component of the monetary policy announcement.

- *, ** denotes significance at 5 and 1 percent, respectively.

3.1.2 Explanatory minutes’ releases

Consistent with the monetary policy announcement results, explanatory minutes’ releases are found to have an immediate (within 10 min) impact on the Australian foreign exchange market, as reported in Table 2. Specifically, using changes in the 30-day cash rate (90-day bank bill) futures contract as a proxy for surprise, an unexpected 100 basis point increase, derived from the information content of the explanatory minutes, leads to an immediate appreciation of the Australian dollar by 0.232 percent (0.105 percent). This result is significant at the 1 percent (5 percent) level, demonstrating the reach of central bank communication.

| Time to announcement | 30-day cash rate | 90-day bank bill | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | T-statistic | Coefficient | T-statistic | |

| −10, −1 | −0.065 | −2.11* | −0.006 | −0.40 |

| 0,9 | 0.232 | 3.07** | 0.105 | 2.22* |

| 10,19 | −0.031 | −0.84 | −0.011 | −0.54 |

| 20,29 | −0.034 | −1.36 | −0.008 | −0.42 |

| 30,39 | −0.001 | −0.01 | −0.024 | −0.95 |

| 40,49 | −0.010 | −0.20 | −0.040 | −2.11* |

| 50,59 | 0.062 | 2.24* | 0.020 | 1.66 |

| n | 86 | 87 | ||

- Results reported are derived from the model: where Rt represents the percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate using 10-min intervals from t−10 to t60 and Δit represents the unexpected component of the explanatory minutes’ release.

- *, ** denotes significance at 5 and 1 percent, respectively.

Further, using changes in the 30-day cash rate futures contract as a proxy for surprise, there is evidence of pre-announcement price movement, with the Australian dollar depreciating 0.065 percent in the 10 min (−10, −1) prior to an unexpected 100 basis point increase. This result may be indicative of a pre-announcement effect but is not robust when the 90-day bank bill futures contract is substituted to proxy for surprise.

3.1.3 Relative impact of unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases

The relative impact of unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases on the Australian foreign exchange market is reported in Table 3. Using the 30-day cash rate and 90-day bank bill futures contracts to proxy for surprise, this study finds no discernible difference between the impact of an unexpected monetary policy announcement and the explanatory minutes’ release in the Australian foreign exchange market as represented by the absence of significance at β2 and β3. This is inconsistent with extant literature (see Guraynak et al., 2005; Kearns and Manners, 2006; Rosa, 2011), which reports that monetary policy statements have a much larger impact on financial instruments. These prior results, however, may be indicative of the inability to clearly distinguish between monetary policy actions and statements.

| Surprise proxy | α | β1∆it | β2(dEMR) | β3(∆it × dEMR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day cash rate | −0.001 | 0.168 | 0.001 | 0.064 |

| (−1.70) | (4.73**) | (1.51) | (0.76) | |

| 90-day bank bill | −0.001 | 0.204 | 0.000 | −0.100 |

| (−1.75) | (6.71**) | (1.29) | (−1.78) | |

| n | 171 |

- These results are derived from the model: where Rt represents the percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate using 10-min intervals from t(−1,−10) to t(0,9), Δit represents the unexpected component of the monetary policy announcement or explanatory minutes’ release and dEMR is a dummy variable set to 1 for an explanatory minutes’ release and 0 for a monetary policy announcement. Regression coefficients are reported with t-statistics in parentheses.

- *, ** denote significance at 5 and 1 percent, respectively.

3.1.4 Impact on the volatility of the AUD/USD exchange rate

The results of the TGARCH model, reported in Table 4, indicate that unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases elicit a significant change in the volatility of the Australian foreign exchange market, irrespective of the surprise proxy used.

| Monetary policy announcement | Explanatory minutes’ release | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30DYCR | 90DYBB | 30DYCR | 90DYBB | |

| Mean equation | ||||

| α c | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000 |

| α 1 R t−1 | −0.044** | −0.056** | −0.038** | −0.037** |

| α2 (dt(0,9) × Δit) | 0.173** | 0.149** | 0.123** | 0.117** |

| Volatility equation | ||||

| β c | −0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** |

|

0.179** | 0.241** | 0.221** | 0.171** |

|

0.620** | 0.683** | 0.660** | 0.614** |

|

0.063** | 0.104** | 0.081** | 0.060** |

| t (−10,−1) | 0.031** | 0.023** | 0.011** | 0.018** |

| t (0,9) | 0.506** | 0.466** | 0.232** | 0.329** |

| t (10,19) | −0.274** | −0.293** | −0.129** | −0.177** |

| t (20,29) | −0.022** | −0.016** | −0.007 | −0.011 |

| t (30,39) | 0.005 | −0.001 | 0.008 | 0.018** |

| t (40,49) | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.012 |

| t (50,59) | 0.088** | 0.024** | 0.015* | 0.064** |

- Results are derived from the TGARCH model described in Equations (3a) and (3b): where Rt represents the percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate using 10-min intervals from t−10 to t, Rt−1 represents the 10-min lagged percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate and Δit represents the unexpected component of the monetary policy announcement or explanatory minutes’ release. dt is a vector of dummy variables that take the value of 1 in each 10-min interval t (from t−10 to t+60), or 0 otherwise.

- *, ** denotes significance at 5 and 1 percent, respectively.

Of note, the magnitude of the impact following an unexpected monetary policy announcement (0.620/0.683, significant at the 1% level) is akin to the impact following an explanatory minutes’ release (0.660/0.614, significant at the 1% level). Further, the significance and sign of γ denote that the volatility response is asymmetric, that is, stronger to unexpected decreases in the target interbank cash rate (or expectations thereof), than unexpected increases.

The timing of the volatility response, as indicated by the sign and significance of the dummy variable dt, is also shown to vary between the two events. Specifically, volatility rises in the 10 minutes prior to both the monetary policy announcement and the explanatory minutes release and remains elevated for up to 10 minutes, after which volatility reduces, with a more protracted response following a monetary policy announcement.

3.2 Economic conditioning

The reliability of the Australian foreign exchange market response to monetary policy, subject to economic conditioning based on the GFC and the Melbourne Institute's consumer sentiment index, is reported in Sections 3.2.11 and 3.2.22, respectively.

3.2.1 Global Financial Crisis

The impact of monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases on the Australian foreign exchange market during crisis and non-crisis periods is reported in Table 5.

| α | β1∆it | β2(dcrisis) | β3(∆it × dcrisis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Impact of monetary policy announcements during crisis and non-crisis periods | |||

| ABS: July 2008 to March 2009 | |||

| −0.000 | 0.165 | −0.002 | 0.200 |

| (−1.76) | (5.18)** | (−0.96) | (2.08)* |

| BP: 29 November 2006 to 5 January 2010 | |||

| −0.000 | 0.153 | −0.001 | 0.128 |

| (−0.89) | (4.26)** | (−2.08)* | (2.82)** |

| Panel B: Impact of explanatory minutes’ releases during crisis and non-crisis periods | |||

| ABS: July 2008 to March 2009 | |||

| 0.000 | 0.243 | 0.000 | −0.446 |

| (−0.04) | (3.20**) | (−0.47) | (−2.90)** |

| BP: 29 November 2006 to 5 January 2010 | |||

| 0.000 | 0.227 | 0.000 | −0.368 |

| (−0.33) | (2.79)** | (−0.07) | (−2.68)** |

- These results are derived from the model: where Rt represents the percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate using 10-min intervals from t(−1,−10) to t(0,9), Δit represents the unexpected component of the monetary policy announcement or explanatory minutes’ release and dcrisis is a dummy variable set to 1 if the announcement occurs during the Global Financial Crisis, or 0 otherwise. ABS = Australian Bureau of Statistics (2013); BP = Bai and Perron (1998). Regression coefficients are reported with t-statistics in parentheses.

- *, ** denote significance at 5 and 1 percent, respectively.

Monetary policy announcements

The results indicate that the impact of monetary policy announcements on the Australian foreign exchange market intensified during the GFC. This is demonstrated in Panel A of Table 5, which reports that an unexpected 100 basis point easing of the target interbank cash rate led to a depreciation of the Australian dollar by 0.365 percent (0.281 percent) during the GFC and 0.165 percent (0.153 percent) during non-crisis periods, when the crisis period is exogenously (endogenously) defined. This result represents an additional depreciation of the Australian dollar by 0.200 percent (0.128 percent) during the GFC, a difference which is statistically significant at the 5 percent (1 percent) level.

This result is inconsistent with Zettlemeyer (2004) and Pennings et al. (2015), who find no robust evidence that monetary policy is more or less effective during crisis periods. However, it is not unexpected, due to the use of an alternate intraday surprise measure and narrower event windows. Both methodological changes were suggested by the authors of the latter study to overcome limitations of measurement error and accuracy.

Explanatory minutes’ releases

Panel B of Table 5 reports the impact of explanatory minutes’ releases on the Australian foreign exchange market during the GFC. These results suggest that the Australian foreign exchange market viewed the explanatory minutes’ releases with trepidation during the GFC. This is demonstrated by the significance (at the 1 percent level) and offsetting nature of the coefficient at β3, irrespective of the crisis definition employed (exogenous or endogenous). En masse, this suggests that during the GFC, the Australia foreign exchange market only responded to central bank actions (the monetary policy announcement), not explanations (explanatory minutes’ releases).

3.2.2 Sentiment

Further evidence suggesting that the effectiveness of monetary policy varies in different economic states is provided by the Melbourne Institute's consumer sentiment index. The effect of consumer sentiment on the impact of monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases in the Australian foreign exchange market is reported in Table 6.

| α | β1∆it | β 2 d csi | β3(∆it × dcsi) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Effect of sentiment on monetary policy announcements | |||

| −0.000 | 0.138 | −0.001 | 0.081 |

| (−0.19) | (5.64)** | (−1.43) | (2.14)* |

| Panel B: Effect of sentiment on explanatory minutes’ releases | |||

| 0.000 | 0.173 | −0.000 | −0.287 |

| (0.40) | (2.50)* | (−1.00) | (−2.09)* |

- These results are derived from the models: where Rt represents the percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate using 10-min intervals from t(−1,−10) to t(0,9), Δit represents the unexpected component of the monetary policy announcement or explanatory minutes’ release and the dummy, dcsi, is set to 1 when the 12-month moving average of the consumer sentiment index is greater than the index value at the time of the announcement (a negative sentiment announcement), or zero (0) if it is at or below the index value at the time of the announcement (a positive sentiment announcement). Regression coefficients are reported with t-statistics in parentheses.

- *, ** denote significance at 5 and 1 percent, respectively.

Monetary policy announcements

Consistent with Akhtar et al. (2011) and Loundes and Scutella (2000), results from the estimation of Equation 5) confirm that consumer sentiment influences the AUD/USD exchange rate. This is shown in Panel A of Table 6, which reports that the percentage change in the AUD/USD exchange rate following unexpected monetary policy announcements is explained by the size of the surprise (Δit) and the level of consumer sentiment (dcsi).

The positive and significant coefficient (0.081) on the interaction of the surprise and consumer sentiment variable, β3(Δit × dcsi), suggests an asymmetric response in the Australian foreign exchange market consistent with Akhtar et al. (2011). Specifically, that following an unexpected tightening (easing) in the target interbank cash rate, the Australian dollar will appreciate (depreciate) further in negative sentiment periods.

Explanatory minutes’ releases

Consistent with the GFC results, this study finds that consumer sentiment influences the impact of explanatory minutes’ releases on the Australian foreign exchange market. This is demonstrated in Panel B of Table 6, which reports a negative and statistically significant coefficient (−0.287) on the interaction term, β3(Δit × dcsi). The offsetting nature of this coefficient suggests that in periods of low sentiment, the Australian foreign exchange market does not respond to news derived from the information content of the explanatory minutes’ release. Again, it is implied that central bank actions rather than statements are required to institute change in poor economic states.

4 Conclusion

This study exploits a unique feature of the Australian monetary policy environment, the discrete announcement of monetary policy actions and communications, to examine first, the differential impact of monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases on the Australian foreign exchange market to determine the reach of central bank communications, and second, monetary policy impact subject to different economic states to determine reliability.

First, this study finds that unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases impact the Australian foreign exchange market within 10 minutes. Specifically, an unexpected 100 basis point increase (decrease) in the target interbank cash rate leads to an immediate appreciation (depreciation) of the Australian dollar between 0.149 and 0.174 percent. Similarly, positive (negative) news, derived from the information content of the explanatory minutes, leads to an immediate appreciation (depreciation) of the Australian dollar between 0.105 and 0.232 percent.

When the relative impact of monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases are examined, no discernible difference in the Australian foreign exchange market is found. This is inconsistent with previous studies that tortuously examine the impact of these two events contemporaneously (Guraynak et al., 2005; Kearns and Manners, 2006; Rosa and Verga, 2008; Rosa, 2011) rather than in isolation.

Further, unexpected monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases are shown to elicit a significant change in the volatility of the Australian foreign exchange market, irrespective of the surprise proxy used. This response is found to be asymmetric, stronger to unexpected decreases in the target interbank cash rate (or expectations thereof) than unexpected increases. Further, the timing of the response is shown to vary between the two events, with a more protracted response following monetary policy announcements. Taken together, these results demonstrate that central bank actions and communications have a comparable reach and therefore can be used interchangeably to stimulate economic recovery.

Second, this study presents new evidence that the GFC and consumer sentiment affect the reliability and impact of both monetary policy announcements and explanatory minutes’ releases in the Australian foreign exchange market. Namely, during the GFC and in low sentiment periods, the impact of the monetary policy announcement strengthens, whilst the impact of the explanatory minutes’ release is negated. This result suggests that during poor economic states, the market reacts to central bank actions, not explanations. Put simply, at these times, monetary policy actions speak louder than words, an adage that in this context provides actionable information for central bank regulators.

Notes

References

- 1 The ‘last traded’ price in the last (first) minute of trade prior to (following) the announcement is employed to avoid using stale quotes/prices consistent with Smales (2013).