Whose Job Is it Anyway?

As health care providers we all seek to do good for our patients, or at the very least, do no harm. This core principle is and always should be independent of where one is educated or trains, specialty, practice setting, payer mix, etc. However, interlaced with this is a self-protective mechanism that draws a line in the sand when it comes to action or inaction for certain aspects of patient care. For emergency physicians, the distinction of “my job” versus “your job” often hinges on the perceived acuity of the condition, with a general tendency to abdicate responsibility for things that are felt to be chronic and, for the most part, can be effectively managed by a primary care provider. While we are not alone in this perspective—indeed kicking the can into someone else's road is all too common in medicine—we are unique as emergency departments (EDs) have a legal (and daresay moral) obligation to provide a medical screening examination in one form or another to all who enter our doors.

What then should we do when our screening reveals something that could, unequivocally, do long-term harm to our patients? This conundrum could be boundless if the basket of items screened for were to expand beyond the realm of what is deemed medically necessary for a given encounter. Fortunately, there is consensus that, at the least, things such as blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory status are crucial, providing objective signs of an individual's physiologic vitality. When abnormal, the latter two are generally seen as reliable indicators of an acute problem; the former is not as easy to interpret. To wit, hypotension, is an undeniable marker of instability yet the same cannot be said for elevated blood pressure—an exceedingly common finding in our setting—as it rarely represents a true emergency.1 However, hypertension itself is widely recognized as the single most important risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease and failure to achieve blood pressure control is a major contributor to premature morbidity and mortality worldwide. Despite this, there has been reluctance on the part of emergency physicians and the specialty as a whole, to espouse public health considerations as they relate to elevated blood pressure in the ED.2, 3 Specific barriers that have been cited by clinicians include a disbelief in the accuracy of ED blood pressures (a consideration that has been largely disproven4-6), a lack of time to address nonacute problems, concerns about lacking continuity for ongoing management, and perspectives that intervening will encourage future inappropriate use of the ED for primary care.7, 8

It is with this backdrop that Meurer and colleagues9 devised Reach Out ED—a pilot study of text message support that was primarily designed to compile feasibility data to justify a subsequent large-scale, randomized controlled trial aimed at testing the effect of a mobile-health (mHealth) behavioral intervention on blood pressure control for ED patients. While there are some unique aspects of this effort such as the use electronic health alerts to identify potentially eligible subjects, this is far from the first attempt to systematically address the problem of elevated blood pressure in the ED. Similar studies with similar goals and methods have been undertaken including a recently completed trial evaluating a text message intervention for hypertension (BPMED) that also demonstrated the ability to effectively maintain postdischarge communication with enrolled ED participants over a 30-day follow-up period.10 While both studies focused on hypertension, Meurer et al.9 enrolled a cohort that was predominantly white (75%) and insured (100%) with a high rate of stable primary care (91%). In contrast, BPMED included only African Americans, most of whom (68%) were low socioeconomic status (annual income < $20,000), with split recruitment of patients from the ED (n = 65) and local primary care clinics (n = 58). Moreover, only 75% of the cohort of Meurer et al. carried a baseline diagnosis of hypertension and just 48% reported taking antihypertensive therapy at the time of randomization, while BPMED exclusively enrolled patients with known hypertension, all of whom had to be on at least one blood pressure medication to be eligible. Such differences might have impacted what is perhaps the most important study result with a substantially higher postrandomization dropout rate for Reach Out ED (45%) compared to BPMED (11% overall; 12% for those recruited from the ED versus 9% from primary care). Although such a difference may seem paradoxical with greater retention among a higher risk cohort, on closer analysis it makes logical sense as individuals with hypertension who are actively being treated for it may be more engaged in efforts to improve self-management and thus more compliant with a bidirectional exchange through text messaging. In addition, individuals with lesser socioeconomic means may be more receptive to opportunities that provide ongoing, supportive interactions with healthcare providers—something that is often lacking in underserved communities.

Given that the stated purpose of Reach Out ED was to derive pilot data to inform a subsequent larger study, nuances of the enrolled cohort are highly relevant to future research aimed at improving hypertension control for ED patients. The high dropout rate postrandomization suggests that the intervention may not have resonated with the target population—an assertion that is supported by the fact that 30% of those initially identified during the screening phase did not respond to a single text message postenrollment. As we and others have written, inclusion of patients who are the intended recipients of an intervention during the design phase is critical to both acceptance and uptake11such outreach in Reach Out ED might have identified unappreciated considerations and enhanced trial success. Like Reach Out ED, BPMED also provided pilot data that was successfully leveraged to secure NIH funding (1 R01 HL127215; Buis, PI) for an ED specific trial of multicomponent mobile health support (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02955537).12 Known as MI-BP (mHealth to Improve Blood Pressure Control in Hypertensive African Americans), this study incorporates perspectives from our Detroit-based hypertension community advisory board in its design and is well under way with randomization of more than 75 participants to date. Collectively, these two follow-up investigations will help to determine the efficacy of mobile health supported behavioral interventions to reduce blood pressure.

In addition to providing insights into what may influence retention in ED-based clinical trials aimed at improving hypertension self-management, Reach Out ED provides an intriguing lesson in how to (and how not to) interpret related blood pressure data in such studies. Simply put, in a study where short-term blood pressure change is an endpoint yet data are incomplete for nearly half the participants, imputation of missing values using a last observation carried forward or any other correction method is not valid. This is particularly true when such missingness may not be random, duration of the exposure and lag time from baseline measurement may not be consistent, and important group imbalances are known to exist. Case in point, 33% of control versus 57% of intervention patients were on baseline antihypertensive therapy yet analyses stratified by this variable suggest potentially greater benefit in controls. However, no data are provided on the proportion of participants in each group who completed the study that were actually on baseline antihypertensive therapy. Knowing this and the relative blood pressure changes within respective subgroups would have been informative. Finally, as acknowledged by the authors, the lack of information on what therapeutic adjustments, if any, were initiated during the course of follow-up is a critical limitation that really precludes any interpretation of causal relationships.

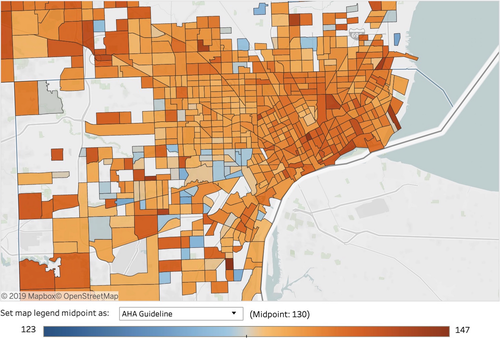

Perhaps the greatest value of studies like Reach Out ED and BPMED, as well as their NIH-funded follow-up trials, is that they call attention to the issue of uncontrolled hypertension and remind us that EDs do indeed have an important role to play in battling this epidemic. Figure 1, which displays aggregated data from 551,690 Detroit-based ED encounters (77% African American) over a 26-month period compiled as part of our ongoing Hypertension Surveillance Project, highlights the overwhelming magnitude of this problem, with mean systolic blood pressures that exceed the current guideline threshold of 130 mm Hg in nearly every census tract. When faced with such facts, the imperative is clear. EDs must be involved in systematic efforts to address this crucial public health challenge and emergency physicians must recognize that doing so does not deviate from our job but instead reflects the nobility of our profession.