The Relationship Between a Chief Complaint of “Altered Mental Status” and Delirium in Older Emergency Department Patients

La Relación entre el Motivo de Consulta Principal “Estado Mental Alterado” y el Delirium en los Pacientes Mayores en el Servicio de Urgencias

Abstract

enBackground

Altered mental status is a common chief complaint among older emergency department (ED) patients. Patients with this chief complaint are likely delirious, but to the authors' knowledge, this relationship has not been well characterized. Additionally, health care providers frequently ascribe “altered mental status” to other causes, such as dementia, psychosis, or depression.

Objectives

The objective was to determine the relationship between altered mental status as a chief complaint and delirium.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of a cross-sectional study designed to validate three brief delirium assessments, conducted from July 2009 to March 2012. English-speaking patients who were 65 years or older and in the ED for <12 hours were included. Patients who were comatose or nonverbal or unable to follow simple commands prior to the acute illness were excluded. Chief complaints were obtained from the ED nurse triage assessment. The reference standard for delirium was a comprehensive psychiatrist assessment using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision criteria. Sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (LR), and negative LR with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the psychiatrist's assessment as the reference standard.

Results

A total of 406 patients were enrolled. The median age was 73.5 years old (interquartile range [IQR] = 69 to 80 years), 202 (49.8%) were female, 57 (14.0%) were nonwhite race, and 50 (12.3%) had delirium. Twenty-three (5.7%) of the cohort had chief complaints of altered mental status. The presence of this chief complaint was 38.0% sensitive (95% CI = 25.9% to 51.9%) and 98.9% specific (95% CI = 97.2% to 99.6%). The negative LR was 0.63 (95% CI = 0.50 to 0.78), and the positive LR was 33.82 (95% CI = 11.99 to 95.38).

Conclusions

The absence of a chief complaint of altered mental status should not reassure the clinician that delirium is absent. This syndrome will be missed unless it is actively looked for using a validated delirium assessment. However, patients with this chief complaint are highly likely to be delirious, and no additional delirium assessment is necessary.

Resumen

esIntroducción

El estado mental alterado (EMA) es un motivo de consulta principal frecuente en pacientes mayores que consultan al servicio de urgencias (SU). Este motivo de consulta principal en estos pacientes corresponde con más frecuencia a delirium, pero según el conocimiento de los autores, esta relación no ha sido bien caracterizada. Además, los sanitarios frecuentemente relacionan EMA a otras causas, como la demencia, la psicosis o la depresión.

Objetivos

El objetivo fue determinar la relación entre EMA como motivo de consulta principal y el delirium.

Metodología

Análisis secundario de un estudio transversal diseñado para validar tres valoraciones breves de delirium, llevado a cabo de julio de 2009 a marzo de 2012. Se incluyeron los pacientes de habla inglesa que tenían 65 años o más de edad y que estuvieron menos de 12 horas en el SU. Se excluyeron los pacientes en coma o que tenían demencia en estadio terminal. Los motivos de consulta principales se obtuvieron de la valoración del triaje de enfermería del SU. El estándar de referencia de delirium fue una valoración psiquiátrica global usando los criterios revisados DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, cuartra edición). Se calculó la sensibilidad, la especificidad, la razón de probabilidad positiva y la razón de probabilidad negativa con sus intervalos de confianza al 95% usando la valoración del psiquiatra como estándar de referencia.

Resultados

Se incluyeron un total de 406 pacientes. La mediana de edad fue de 73,5 años (rango intercuartílico: 69 a 80 años), 202 (50%) fueron mujeres, 57 (14%) de raza no blanca y 50 (12,3%) tuvieron delirium. Veintitrés pacientes (5,7%) de la cohorte tuvieron como motivo de consulta principal EMA. La presencia de este motivo de consulta principal tuvo una sensibilidad de un 38,0% (IC 95% = 25,9% a 51,9%) y una especificidad de un 98,9% (IC 95%= 97,2% a 99,6%). La razón de probabilidad negativa fue 0,63 (IC 95% = 0,50 a 0,78) y la razón de probabilidad positiva fue 33,82 (IC 95% = 11,99 a 95,38).

Conclusiones

La ausencia de un motivo de consulta de EMA no debería hacer pensara al clínico que el delirium está ausente. El diagnóstico de este síndrome se perderá a menos que se busque activamente usando un valoración validada de delirium. Sin embargo, los pacientes con EMA como motivo de consulta principal es más probable que padezcan delirium y que no sea necesaria una valoración de delirium adicional.

Delirium affects approximately 1.9 million older emergency department (ED) patients in the United States each year.1 Despite its association with adverse outcomes,2 this form of organ dysfunction is missed 76% of the time because it is not routinely screened for in the ED.3 The ED is a dynamic and fast-paced environment and routine delirium assessment in all older patients may not be feasible. Quick and easy methods to identify patients with delirium are needed to improve recognition.

“Altered mental status” is a common chief complaint among older ED patients, yet to our knowledge, its relationship to delirium has not been quantified in the literature. If the presence of this chief complaint is highly sensitive and specific for delirium, then routine delirium screening would not be needed in the ED. We conducted this investigation to determine the diagnostic performance of altered mental status as a chief complaint in detecting delirium in older ED patients.

Methods

Study Design

This was a preplanned secondary analysis of a prospective observational study.4 The local institutional review board reviewed and approved this study.

Study Setting and Population

The study was conducted at a tertiary care, academic ED. The details of the methods have been previously described.4 In summary, a convenience sample of patients was enrolled from July 2009 to February 2012. Enrollment occurred from Monday through Friday between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. Because of the extensiveness of the psychiatric evaluations, enrollment was limited to one patient per day. Patients were included if they were 65 years or older, in the ED for less than 12 hours at the time of enrollment, and not in hallway beds. Patients were excluded if they were non–English-speaking, previously enrolled, deaf or blind, comatose, nonverbal, or unable to follow simple commands prior to the acute illness or did not have a psychiatrist assessment.

Study Protocol

Altered Mental Status Determination

Each patient's chief complaint was recorded from the nurse's triage assessment, which is the initial assessment performed for all ED patients regardless of mode of arrival (walk-in, ambulance, helicopter, etc.). The nurse's triage assessment was recorded electronically. The chief complaint was chosen from a prepopulated list and was based on the patient's most prominent reason why he or she was in the ED. The patient was usually assigned the chief complaint of altered mental status if the phrases such as “confused” or “not acting right” were used. For patients who arrived by ambulance, were unable to provide a history, and did not have surrogates present, the triage nurses usually used the prehospital run sheet (history and physical) to obtain the chief complaint. Once the triage note was finalized into the medical record, a research assistant then copied the ED chief complaint into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database verbatim. This was then double-checked for accuracy by the principal investigator (JHH).

Reference Standard for Delirium

All enrolled patients received the reference standard for delirium, which was a comprehensive consultation-liaison psychiatrist assessment using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision criteria.5 Three psychiatrists performed the assessments and had an average of 11 years of clinical experience. Diagnosing delirium was a routine part of their daily clinical practice. They used all means of patient evaluation and testing, as well as data gathered from those who best understood each patient's current mental status (e.g., the patient's surrogates, physicians, and nurses). They performed bedside cognitive tests and focused neurologic examinations and also evaluated for affective lability, hallucinations, and arousal level. If the diagnosis of delirium was uncertain, confrontational naming, proverb interpretation or similarities, and assessments for apraxias were also performed at the discretion of the reference psychiatrists to achieve diagnostic certainty.

Data Analysis

The sample size was based on the original study, which validated the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM).4 Because approximately 10% of older ED patients are delirious, our sample size calculations were based on the precision of the bCAM's sensitivity and that a 95% lower confidence limit of 75% would be acceptable. Because we hypothesized that the bCAM would be 90% sensitive, we estimated that we would need to enroll 50 patients with delirium.

Measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables were reported as proportions. Sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (LR), and negative LR with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the psychiatrists' assessments as the reference standard. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

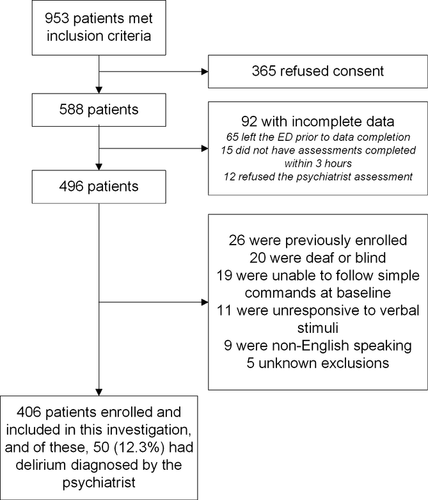

A total of 953 patients were screened, 406 patients met enrollment criteria (Figure 1), and of these, 50 (12.3%) were delirious as diagnosed by the psychiatrists. Their characteristics can be seen in Table 1. Enrolled patients were similar in age and sex compared with all potentially eligible patients who presented to the ED during the study period, but they were more likely to be admitted and have chief complaints of chest pain (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Enrolled Patients (n = 406) | All Potentially Eligible Patients (N = 22,168) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 73.5 (69–80) | 74 (69–81) |

| Female sex | 202 (49.8) | 11,969 (54.0) |

| Nonwhite race | 57 (14.0) | — |

| Education | — | |

| Elementary or below | 9 (2.2) | — |

| Middle school | 48 (11.8) | |

| High school | 163 (40.2) | |

| College | 118 (29.1) | |

| Graduate school | 67 (16.5) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | |

| Nursing home residence | 11 (2.7) | — |

| Dementia in medical record | 24 (5.9) | — |

| ED chief complaint | ||

| Abdominal pain | 17 (4.2) | 1,222 (5.5) |

| Altered mental status | 23 (5.7) | 1,002 (4.5) |

| Chest pain | 67 (16.5) | 2,297 (10.4) |

| Generalized weakness | 40 (9.9) | 1,546 (7.0) |

| Shortness of breath | 46 (11.3) | 2,035 (9.2) |

| Syncope | 23 (5.7) | 608 (2.7) |

| Admitted to the hospital | 294 (72.4) | 13,533 (62.1) |

- Data are reported as n (%) unless otherwise noted.

- IQR = interquartile range; — = not collected.

The median time between the triage note and psychiatrist assessment was 234 minutes (IQR = 162 to 336 minutes). Twenty-three (5.7%) of the cohort had chief complaints of altered mental status. The presence of this chief complaint was 38.0% sensitive (95% CI = 25.9% to 51.9%) and 98.9% specific (95% CI = 97.2% to 99.6%) for the diagnosis of delirium. The negative LR was 0.63 (95% CI = 0.50 to 0.78) indicating that the absence of a chief complaint of altered mental status did not substantially reduce the likelihood of delirium. However, the positive LR was 33.82 (95% CI = 11.99 to 95.38) indicating that the presence of altered mental status as a chief complaint strongly increased the likelihood of delirium.

Discussion

We observed that a chief complaint of altered mental status in older ED patients is insensitive for delirium, and the absence of this chief complaint should not reassure the ED health care provider that delirium is absent. This underscores the point that the majority of older ED patients with delirium will not have chief complaints of altered mental status and will be missed without actively looking for it using a validated delirium assessment; the Confusion Assessment Method and Brief Confusion Assessment Method are examples of delirium assessments that have been validated for use in older ED patients.4, 6, 7 Missing delirium in the ED is considered a safety concern and may have downstream implications.8 A delirious patient is less likely to provide an accurate reason of why he or she is in the ED, and missing delirium may lead to an inadequate diagnostic work-ups, delays in the diagnosis of the underlying medical illness, and inappropriate discharge to the psychiatric hospital or home.9, 10 Approximately 25% of ED patients with delirium are discharged to home.1 These patients are less likely to understand their discharge instructions, which may lead to decreased compliance.9, 11 If admitted, delirium that is missed in the ED will also be missed in the inpatient setting in over 95% of cases.3

Conversely, the presence of altered mental status as a chief complaint is nearly diagnostic of this syndrome as evidence of the very high positive LR (~33), which is widely considered to sway clinical decision-making.12 A delirium assessment is not needed in these patients and would save the ED health care providers both time and resources. Patients with this chief complaint should undergo comprehensive diagnostic work-ups to rule out underlying medical illnesses that precipitated the delirium.13

To our knowledge, no other study has investigated the diagnostic accuracy of an ED chief complaint of altered mental status for delirium. In the inpatient setting, Inouye et al.14 evaluated a chart-based method to diagnose delirium that looked for medical record documentation of an acute confusional state; they observed that this method was 74% sensitive and 83% specific. The differences between their sensitivity and specificity and ours likely reflect differences in chart abstraction methods. We examined the presence of altered mental status as an ED chief complaint, which is the primary reason why the patient is in the ED at a single point in time (initial nurse's triage assessment). The chart review method of Inouye et al. reviewed all components of the medical record including the notes of the nurses, treating physicians, consultants, physical/occupational therapists, and social workers throughout hospitalization.

Limitations

This study was conducted in a single center and may not be generalizable to other settings. We also enrolled a convenience sample, which may have introduced selection bias. Based on the higher admission rate, enrolled patients may have had higher severities of illness and this may have introduced spectrum bias. The reliability of the nurse's chief complaint entry was not tested, and this is an acknowledged weakness of our study. The assessing psychiatrist had full access to each patient's medical record including the triage chief complaint. This may have introduced incorporation bias, which can falsely elevate sensitivity and specificity. However, the presence of inattention, and not altered mental status, was considered to be a core diagnostic feature for delirium and was evaluated for using comprehensive bedside cognitive testing.5, 15 Because a median of 4 hours elapsed between them, discrepancies between the nurse's triage and psychiatrist's assessments may have occurred as a result of time. This may have overestimated or underestimated the diagnostic accuracy of altered mental status as a chief complaint. We did not evaluate the reliability of the psychiatrist's DSM-IV-TR assessment. Having a second psychiatrist perform a comprehensive evaluation would not have been feasible for the ED setting as it would have placed an undue burden on the patient. To minimize this bias, we used consultation-liaison psychiatrists who had a wealth of experience in diagnosing delirium.

Conclusions

The absence of altered mental status should not reassure the clinician that delirium is absent. This syndrome will be missed unless it is actively looked for using a validated delirium assessment. However, patients with this chief complaint are highly likely to be delirious and no additional delirium assessment is necessary. These patients should undergo comprehensive diagnostic work-ups to uncover the underlying etiologies.

We thank Vanderbilt Emergency Medicine's research assistants (Cosby Arnold, Adrienne Baughman, Edwin Carter, Charity Graves, Donna Jones, Kelly Moser, and Dennis Reed) who helped collect the data. We thank Amanda Wilson, MD, John Shuster, MD, and John Vernon, MD, for performing the reference standard assessments. We also thank Donna Jones, EMT, and Karen Miller, RN, MPA, for study coordination.