Observability and Subjective Performance Measurement

Abstract

Accounting research provides theory and evidence on the choice and use of subjective performance measures for evaluating managerial performance. However, accounting research does not focus on the subjective performance measurement of managerial behaviour once measures have been chosen. We extend accounting research by investigating the factors that influence the subjective performance measurement decision. We predict that the level of subjective performance measurement is influenced by the informativeness of financial performance measures and by the verifiability of the nonfinancial measures in a formula-based incentive plan. We expect that the measures' informativeness and verifiability depends on the observability of both the managerial behaviour being subjectively measured and the reliability of the financial and nonfinancial performance measures. More specifically, we hypothesize that the influence of the levels of the financial performance measures on the level of subjective performance measurement is moderated by the observability of either the managerial behaviour being measured (for the financial measures) or the performance measures' reliability (for the nonfinancial measures). Data from a firm provide support for our hypotheses.

The accounting literature investigates the benefits and costs of the choice and use of performance measures for evaluating and rewarding managerial performance (e.g., Bushman et al., 1996; Ittner and Larcker, 1998a, 2001, 2009; Hayes and Schaefer, 2000; Murphy and Oyer, 2003; Gibbs et al., 2004). While the majority of such research is focused on objective financial measures, researchers are increasingly investigating subjective performance measures, consistent with practitioners' reliance on them. For example, General Electric measures its managers' performance based on their external focus, decisiveness, inclusiveness, risk taking, domain expertise, leadership, innovation, and growth (Colvin, 2006a, b). Subjective performance measurement occurs when people use their discretion to cognitively measure an object (e.g., managerial behaviour, product quality) that creates less verifiable information (e.g., audited or auditable) (Moers, 2006; Rajan and Reichelstein, 2009). Subjective performance measures are valuable in performance evaluation and reward systems when they are informative about the qualitative aspects of managers' behaviour, beyond the information provided by objective performance measures (Ittner and Larcker, 1998a, 2001, 2009).

The accounting literature includes investigations about the appropriateness of using subjective measures in performance evaluation (e.g., Ittner et al., 2003; Rajan and Reichelstein, 2006), the factors influencing the choice of subjective measures (Bushman et al., 1996; Murphy and Oyer, 2003; Gibbs et al., 2004; Hoppe and Moers, 2011), and various bias and sub-optimal results of subjective measures in performance evaluation (e.g., Moers, 2005; Bol, 2011; Bol and Smith, 2011; Woods, 2012).1 In contrast to the current body of accounting research, which provides theory and evidence on the choice and use of subjective performance measures for evaluating managerial performance, we extend the literature by investigating the factors that influence subjective performance measurement after the measures have been chosen.

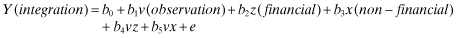

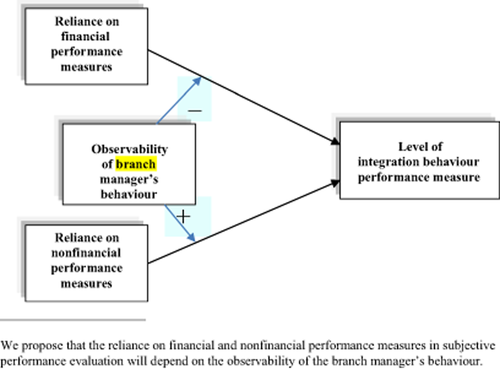

Through the use of proprietary archival data and extensive executive interviews, we examine how an evaluator's subjective performance evaluation decision is affected by the manager's opportunity to verify the financial and nonfinancial measures of sales branch managers' performance. We use the evaluator's observability of the manager to proxy for the verification process as well as the level of informativeness of other measures. We ask: Do financial and nonfinancial performance measures reinforce a complex evaluation of integration behaviour and does observability increase or decrease their influence?

In this study, subjective performance measurement occurs in the context of the general sales manager from a firm's home office (home office manager) subjectively measuring a sales branch office manager's ‘integration’ behaviour by judging that behaviour in relation to pre-established but undefined criteria, which includes his ability to work in a team, proactive job attitude, communication, on-time reporting, customer service, and creativity.

Consistent with the analytical literature (Baker et al., 1994; Baiman and Rajan, 1995), we consider the case in which the formula-based contract has no discretion (with respect to the weights of the financial and nonfinancial measures) and examine how the subjective measure is influenced by the informativeness of the other measures in the contract. Consistent with maintained assumptions in the literature, and verified through interviews with the key informants of our case (see Research Site section), the subjective measure was specifically included in the incentive system to capture dimensions of managerial performance that were not already captured by the financial measures or the nonfinancial measure (customer satisfaction) in the incentive system.

Given this incentive system, with purportedly independent informative components, and the bounded rationality of the evaluator, we argue that there will be a spillover effect (Ittner and Larcker, 1998b) between the financial and nonfinancial performance measures and the subjective performance measurement. We argue that this spillover effect will depend on the measures' reliability and informativeness about the branch manager's integration behaviour and that such an effect will vary depending on the level of direct observation by the home office manager (i.e., the evaluator) of a branch manager. Given the reliability and verifiability of financial measures, we argue that the informativeness of the financial measures decreases with increasing time spent on the direct observation of a branch manager by the home office manager. Thus, we hypothesize that the influence of the levels of a branch's financial performance measures on the level of subjective performance measurement decreases with the home office manager's observations of the branch manager's integration behaviour.

The branch nonfinancial performance measure is a regular survey of customer satisfaction that is compiled by the sales department. The measure is neither measured by our firm's accountants using our firm's accounting system nor verified by its auditors. As we explain in the site details, we expect that any reliance on the measure in making the subjective performance measurement will depend on how reliable the manager believes it to be. He can learn about its reliability by verifying it when he visits customers. Therefore, when he has more visits with customers, he learns that it is reliable and thus will rely more on it when subjectively measuring the branch manager's integration behaviour. In short, we predict that the informativeness of the nonfinancial performance measure about a branch manager's integration behaviour depends on the opportunity the home office manager has to verify the measure, which depends on his observation of the customer. Thus, we hypothesize that the influence of the levels of a branch customer satisfaction measure on the level of subjective performance measurement increases with the home office manager's observation of the branch manager's customers.

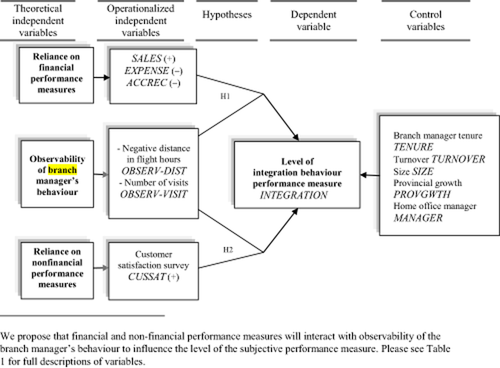

To test our hypotheses, we use archival data for five years from 26 branch offices (including the home sales office) of our firm (TTE). TTE has a formula-based performance evaluation plan that provides annual bonuses to branch managers based on the three branch financial performance measures (sales, expenses, and accounts receivable) and two nonfinancial measures (customer satisfaction and branch manager's integration behaviour).2 Of these measures, the home office manager is responsible for subjectively measuring each branch manager's integration behaviour. Integration behaviour refers to a branch manager's behaviour that is not expected by top management at the home office to be completely, directly, or immediately captured by the financial performance measures, such as a branch manager's communication, teamwork, proactive job attitude, and creativity (see Appendix A). The home office manager's direct observation of a branch manager and branch customers is operationalized as the number of flight hours (distance) and the number of visits made, on an annual basis, by a home office manager to a branch office.3

As hypothesized, as observability increases, we find evidence that the influence of the levels of one of the three financial performance measures (sales) on the level of subjective performance measurement decreases. Also, we find evidence that as observability increases, the influence of the level of the customer satisfaction performance measure on the level of subjective performance measurement increases.

This study extends accounting research in two ways. First, instead of focusing on the use of performance measures for evaluating and rewarding managers, we consider how financial and nonfinancial performance measures influence subjective performance measurement after the measures have been chosen. Second, we use economics and psychology theory to show that the association of financial and nonfinancial performance measures and subjective performance measurement is likely to depend on the measurer's opportunity to observe the object of the subjective assessment, which affects the measurer's perceived reliability and informativeness of the nonfinancial and financial performance measures.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Performance Measurement

Management accounting research has investigated how performance measurement properties, such as informativeness, influence their use in rewarding performance, as predicted by economic theory (Ittner and Larcker, 1998a, 2009). Informative performance measures are sensitive to a manager's actions, precise (low noise), and provide incremental information about a manager's actions (Ittner et al., 2003). For a measure to be informative, it must be relevant and faithfully represented. To satisfy the requirement of faithful representation, a measure needs to be verifiable by an independent party (e.g., an auditor) (Moers, 2006; Rajan and Reichelstein, 2009). Verifiability in agency literature has been used to describe whether a signal can be contracted upon (i.e., observable by a third party, e.g., the courts). Agency theory models of aggregation suggest that the informativeness of one measure is dependent on the level of informativeness of another measure (Banker and Datar, 1989). That is, performance measures should receive more weight in an incentive contract when it is more sensitive and/or less noisy about managerial actions. Studies such as Lambert and Larcker (1987), Clinch (1991), and Sloan (1993) provide evidence consistent with this.

Empirical research to date has examined incentive schemes where the weighting of the measures in a formula-based incentive plan can vary, and superiors in organizations have discretion and incentives to bias the performance evaluation (Prendergast and Topel, 1993; Moers, 2005). For example, Moers (2005) examined an incentive plan in which the weights of the constituent measures were allowed to vary and found that the use of multiple objective performance measures and the use of subjective performance measures are related to more compressed and lenient performance ratings that determine annual bonuses. While the setting allows for discretion with respect to the weights of the performance measures, most analytical studies assume that formula-based contracts have zero discretion (Baiman and Rajan, 1995) or that the principal with discretion will not renege because of concerns about reputation (Baker et al., 1994). We consider the case in which the formula-based contract has zero discretion (with respect to the weights of the financial and nonfinancial measures) and examine how the subjective measure is influenced by the informativeness of the other measures in the contract.

Observability

Studies have shown that geographical proximity has economic benefits for monitoring subunits' or subordinates' performance (Lerner, 1995). Closer proximity allows one to acquire superior information about an object that is of interest (e.g., Coval and Moskowitz, 1999, 2001; Ivkovic and Weisbenner, 2005, Bernile et al., 2010) and lowers the monitoring costs (Chhaochharia et al., 2012). There is also a growing body of research in home-bias finance literature that predicts and finds that geographical distance influences investors' decisions and judgements about investees, primarily because of information advantages associated with shorter geographical distances (e.g., visits to the investment). Holding the quality of investments constant, equity investors are more likely to decide to invest in local stocks versus overseas stocks (Kang and Stulz, 1997), and fund managers and individual investors are more likely to decide to invest in firms with headquarters closer to them (Coval and Moskowitz, 1999; Ivkovic and Weisbenner, 2005). The accuracy of forecasts about the earnings of financial analysts is also higher for geographically proximate firms (Malloy, 2005).

Relating to loan officers' loan decisions, Petersen and Rajan (2002) find that loan officers make greater use of objective information when assessing the loans for small business that are more geographically distant. Liberti and Mian (2009) find evidence that is consistent with the theory that greater hierarchical distance between a subordinate and his boss makes it more difficult to incorporate abstract and subjective information in decision-making. They find that higher frequency of interactions between a loan officer and his boss, both over time and through geographical proximity, helps to mitigate the effects of hierarchical distance on information use.

Based on psychometric theory, Wherry and Bartlett (1982) predict that the greater the geographic distance between the evaluator and the evaluatee's workplaces, the lower the probability of multiple and/or long direct experiences. This reduces the evaluator's opportunity to learn about the evaluatee's behaviour by observing or interacting with the evaluatee and thus lowers the probability of deriving an accurate rating. As the number or length of informative experiences decreases, evaluators increasingly rely on other cognitively accessible information to derive their ratings. Expressed in the psychology of decision-making terms (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974), observation enables the development of cognitive accessibility (perceived reliability) of an anchor, which in turn affects the rating decision (Mussweiler and Strack, 2000).

Our review of the performance measurement literature and the effects of direct observation on performance evaluation indicate the following: the effectiveness of the performance evaluation decision depends on the informativeness of the performance measures. The information being assessed during the performance evaluation decision can be about a person or a unit's performance as indicated by the performance measures, or the perceived reliability of information being produced by the performance measures. As with financial statement audits, direct observation enables the evaluator to assess the reliability of nonfinancial performance measures through observing new sources, which in turn increases the perceived reliability of the measure. In the next subsection we develop the arguments for how direct observation of the subordinate moderates the association between objective and subjective performance measures.

Hypotheses Development

(1)

(1)Since the integration measure was included in the incentive system for the purposes of capturing managerial behaviour that is not directly captured by the financial or nonfinancial measurements, both the financial and nonfinancial measures are not expected to be associated with the level of the subjective performance evaluation (integration). To the extent that such a relationship exists, given the bounded rationality of the home office manager, we argue that such relationships will depend on the level of the evaluating manager's direct observation of the branch office manager.

Financial Measures

The influence of performance measures on the performance evaluation decision depends on the informativeness of the performance measures, which can depend partly on the amount of direct observation between the evaluator and the evaluatee (branch office manager). While financial measures are more reliable, they are less likely to be as informative as the nonfinancial measure due to the latter's lead indicator properties (Banker et al., 2000) or because they are less value-relevant (Amir and Lev, 1996). This is particularly likely to be the case in the subjective evaluation context when the evaluating manager's direct observation of the branch manager is high. At high levels of observability, the relative weight of the financial measure signal will be a weaker cue for the subjective evaluation of branch manager performance because of the information gained through direct observation of the branch manager's integration behaviour. That is, compared with the information gained from direct observation, financial measures have less value relevance (Amir and Lev, 1996).

However, as the level of observability of integration behaviour by the home office manager decreases, the associated signal strength of the direct observation decreases and the relative weight of the financial measure signal is expected to increase. Support for this argument comes from two literature streams that have considered observability in the decision-making context. First, in the finance literature, Petersen and Rajan (2002) find that loan officers make greater use of objective information when assessing loans for small business that are more geographically distant. Second, from a psychometrics perspective, Wherry and Bartlett (1982) argue that evaluators increasingly rely on other cognitively accessible information (e.g., objective information) to derive their ratings, as the number or length of informative experiences decreases. In such situations, the other information is likely to include information about the evaluatee that is impounded in cognitively accessible financial performance measures, where the accounting system-based verifiability is independent of direct observation.

Nonfinancial Measures (Customer Satisfaction)

Compared to financial measures, nonfinancial measures are more likely to have lead indicator properties (Banker et al., 2000) and be value-relevant (Amir and Lev, 1996). However, they are less reliable, and they are not verifiable by a system such as accounting and auditors. Therefore, the salience of nonfinancial measures depends in part on direct observation. For example, contact with the object of the nonfinancial measure (e.g., customers) is important because they provide a verifiable basis for the evaluator to assess the reliability of the nonfinancial measure.

Prior studies have found that customers are unlikely to be able to express their firm's level of satisfaction accurately because satisfaction is multidimensional and their response modes in customer satisfaction survey may not capture all aspects of their firm's satisfaction (Hemmer, 1996). Similarly, in the loan officer decision-making setting, Petersen and Rajan (2002) demonstrate that being close to one's customers is likely to facilitate a loan officer's collection of soft information, such as that gathered through face-to-face interaction with a customer. Therefore, as customer visits increase, the principal has greater opportunity to learn about customer satisfaction from an independent source, such that the reliability of the nonfinancial performance measure can be verified. For example, the home office manager can verify the measure by his direct observation of interactions with customers by comparing it to what customers say about their satisfaction levels.

While the economic informativeness of the measure remains constant (i.e., the measure would be expected to rate the same customer satisfaction for both close and distant branch offices), the perceived reliability of the measure is expected to be higher for more observed branch offices, that is, the customer satisfaction measure is perceived to be unreliable until the home office manager assesses it to be reliable, in which case its perceived reliability now depends on its cognitive accessibility through direct observation. Therefore, we predict that the perceived reliability of the nonfinancial measure will be influenced by the measure's cognitive accessibility (the economic informativeness remains constant) as the home office manager's direct observation of customers increases.

Domain of Study Within the Subjective Performance Evaluation Decision

Independent, Dependent, and Control Variables and Hypotheses

Research Site

TTE (a fictional name), a major producer and seller of telecommunications terminal equipment in China, provides equipment to over 200 regional subsidiaries of two Chinese state-owned telecommunications enterprises from 26 branch offices located in 26 provinces. TTE's accounting system includes an Oracle enterprise resource planning system and good internal controls, and the accounting information is verified by external and internal audits.4 Every month TTE's accounting system reports each branch's sales, expenses, and accounts receivable to the home office manager. TTE's performance management system routinely provides the home office manager with customer satisfaction data from every branch. The customer satisfaction performance measurements are subjectively made by customers and not verified by TTE's auditors or other employees.

In the five-year period of our analysis (1998–2003) there were two home office managers. We conducted interviews with the second sales manager as well as with the chief financial officer (CFO). Both managers previously worked in other areas of the firm. When the second home office manager assumed this position in 2001 (he was previously the director of research and development), his approach was to ‘try to learn about performance measurement’ and he was ‘quite confident of every measurement’ he made of the branch managers (Appendix B).

The Incentive Plan

TTE has a formula-based performance evaluation plan that provides annual bonuses to branch managers based on the three branch financial performance measures (sales, expenses, accounts receivable) and two branch nonfinancial measures (customer satisfaction and the branch manager's integration behaviour). The plan comprises a formula in which the Yuan bonus is based on (1) a bonus for sales and (2) a bonus of 4000 Yuan + ((points – 60) * 100 Yuan) with a total of 100 points possible, distributed as 40 for accounts receivable, 5 for expenses, 30 for customer satisfaction, and 25 for integration behaviour. The annual bonus is given to each branch manager and the bonuses range from 60% to 90% of their total annual compensation.5

The financial measures are not adjusted for the effects of uncontrollable variables, but the integration behaviour measure can be adjusted. The weights on the financial and nonfinancial measures used to determine the annual bonuses are fixed. The incentive weights on the performance measures are fixed before the start of each year. The home office manager can neither change the weights, nor directly influence any performance measure except the integration behaviour measure, because the financial measures are from TTE's accounting system and branch customers measure their own satisfaction and send these measurements directly to TTE's home office.

To encourage team spirit among different branch offices, which the sales numbers would not be able to do. (Home office manager)

To encourage managers to be proactive in improving not only their sales capabilities but also their management skills. (Home office manager)

The general manager wants an element of control over the home office relationship with the branch manager and the subjective element is the mechanism used for this purpose. (CFO-VP finance)

When the home office management designed the performance measurement plan, it considered each of the five branch performance measures to measure different aspects of a branch and the manager's behaviour. In other words, the other performance measures were not considered informative about the branch managers' integration behaviour (see Appendix A).6

The Subjective Performance Measurement Decision

Interviews with home office managers (CEO, CFO-VP finance, VP marketing, and home office manager) indicate that their intention was for the home office manager to make accurate measurements of integration behaviour. These home office managers told us that the branch managers' integration behaviour is important for achieving TTE's strategy and financial targets; they consider it to be a leading indicator of financial results. Thus, they want the home office manager's measurements to be accurate, in order to help them assess how well they are achieving TTE's strategy. They do not want the home office manager to use his subjective measurements to game the performance evaluation plan (e.g., by assigning high levels of integration behaviour to branch managers he likes). The CFO-VP finance told us that he was not aware of any gaming of the subjective measurement of integration behaviour. Indeed, the home office manager did not have personal relations with any of the branch managers, in part because he was new to his position and also because of the geographical distance separating him from most branch managers, whom he visits only twice (on average) per year.

The interviews also indicate that the home office manager uses a subjective approach when measuring integration behaviour. He uses his memory and refers to performance measures at the end of the evaluation period to make his subjective measurements: for example, in an interview he said that, ‘I will not deliberately go to find the sales numbers for reference. Rather, I use my memory. For branches that have a good sales record, I remember much clearer. I won't clearly categorize them by numbers, but I get a sense of approximately which category each manager should belong to’ (Appendix B).

Observability—The Branch Visits

The home office manager visits the branch offices to inspect records, interact with the branch manager and branch employees, and meet with customers. ‘I visit every branch office, conduct face-to-face interviews, and talk with the branch employees and branch customers. This is very important in the measurement’ (Appendix B). The visits usually last one or two days and are preferably unannounced. Additional opportunities to gather information about the branch managers' integration behaviour can occur when a branch manager visits the home office to attend quarterly meetings.

The majority of initial visits occurred at the beginning of the year (i.e., right after Chinese New Year). The frequency of visits to branches depends on the distance between a branch and the home office, the performance of the branch, and the importance of the branch's customers to TTE. Additional visits were made to secure large sales transactions with specific customers, which necessitated the presence of the home office manager. Poor performance necessitated visits on only a few occasions and visits were not made for the express reason of acting on complaints received from customers.

During the branch visits, the home office manager is able to meet and directly observe the branch's customers. Direct observation of customers not only allows the home office manager to verify the customer satisfaction measure, it also provides him with concrete and proximate information about customers and their satisfaction. For example, in an interview he stated that the way in which customers talk about the branch manager they deal with is informative about the manager's integration behaviour. When customers are not very satisfied (according to the customer satisfaction measure), they tend to say very little about a branch manager, leading the home office manager to develop the belief that the manager has a poor relationship with the customers and is not providing good customer service. In contrast, more satisfied customers talk more about the branch manager and how he helps their business to be successful. Consistently, the home office manager stated in an interview, ‘In terms of the customer satisfaction measure, I have a higher confidence level for those results which came from customers whom I visited before. The customer satisfaction results influence my subjective measurement of the branch managers’ (Appendix B). Overall the branch visits and customer interactions are potentially informative about the integration behaviour performance of the branch manager.

Research Method

Measurement of Variables

The data consist of annual data for five years (1998–2000 and 2002–2003) for nine (1998), 10 (1999), 17 (2000), and 26 (2002 and 2003) TTE branch offices. The data came from TTE's accounting and performance management system. From 1998 to 2003 data on direct observation (i.e., distance) were available, and in 2002 and 2003 data on direct observation (i.e., visits) were available. We tested the hypotheses with both samples, substituting distance and visits as proxies for direct observation.

Financial performance measures

Branch sales (SALES) is the net sales revenue of products sold. A log transformation is used to reduce skewness in the distribution of SALES. Branch operating expenses (EXPENSE) is the total direct cost of operating a branch office, including salaries and wages, office rent, water, electricity, gas, telephone, office equipment, banquets, entertainment, and business trips. Branch accounts receivable (ACCREC) is defined as total accounts receivable at the end of a reporting period divided by mean credit sales per day.

Non-financial performance measure

Customer satisfaction (CUSSAT) is measured annually via a two-page survey that is returned directly by the customers to the home office. The survey has 20 items that customers use to measure seven attributes of their customer satisfaction: product quality and prices (five items), customer hotline service (three items), on-site customer service (five items), product supply and delivery ability (one item), after-sales product maintenance service (three items), customer staff training and development (two items), and overall satisfaction (one item). Responses to each of the 20 items were captured on a three-point Likert scale, with 1 = Dissatisfied, 2 = Satisfied, and 3 = Very Satisfied. The responses to these 20 items were collated to form a customer satisfaction measure ranging from 20 to 60. While this survey identified seven attributes and three levels of customer satisfaction, it neither defined the attributes, the levels of satisfaction, nor stated the relative importance of each attribute for making the overall satisfaction measurement. As a consequence, the customers' measurement of their satisfaction is subjective because they did not know TTE's intended definition of the attributes and their 20 items and the customer satisfaction measures were not verified by TTE.

Integration behaviour performance (INTEGRATIONt) was measured using TTE's integration behaviour performance measure, which has a theoretical range from 0 to 25 points. The measure includes two general areas of integration behaviour that the home office management desires branch managers to have. The first area includes six types of branch manager integration behaviour: (1) teamwork, including contribution to team spirit, both within and across branch offices; (2) proactive job attitude; (3) work on temporary tasks; (4) communication and work with regional managers on sales to large customers and province-based clients; (5) communication and work with the home office or other branch offices; and (6) sales and promotion activities, on-time monthly and seasonal reporting, and keeping daily working logs. The home office manager should consider these six types of behaviour in making his overall subjective measurement for this general area of integration behaviour on a 15-point scale with 1 = Below expectations on all items and 15 = Exceeded expectations on all items. The second area is customer service (i.e., pro-activeness in following up customer queries and complaints) and the creativity of the branch manager in improving work activities. Similar to the first area, the home office manager should consider customer service and creativity in making his overall subjective measurement of this general area of integration behaviour on a 10-point scale with 1 = Below expectations on both items and 10 = Exceeded expectations on both items.7

Observability (OBSERV) was operationalized in two ways. First, the average commercial flight time in hours between a branch and the home offices was based on information published by the airlines, with observability decreasing with flight time. All branches are accessible from the home office by non-stop flights, except for the farthest branch (Urumchi), which is accessible via a direct flight with one stop. Since flight times vary by airline, for branches with multiple airlines, an average flight time across airlines was computed. Measuring observability using commercial airline flight time, OBSERV-DIST, is consistent with how the managers travel between the branch and home offices.8 Second, we obtained visit data (OBSERV-VISIT) directly from the home office manager for 2002 and 2003. We reversed the OBSERV-DIST variable so that observation increases with either variable. The correlation between the two variables is 0.24 (p < 0.01).

To estimate the coefficients of the interaction terms, we created indicator variables for each of the two continuous OBSERV variables. OBSERV-DIST is an indicator variable, created by splitting the sample at the median airline flight time (1.55 hours) such that OBSERV-DIST is 0 (1) for branch offices equal to or greater (less) than 1.55 hours airline flight time from the home office. Our second indicator variable, OBSERV-VISIT, was created by splitting the sample at the median number of visits (two) such that OBSERV-VISIT is 0 for branch offices with less than two visits (low direct observation) and 1 for branch offices with two or more visits (high direct observation) in each period.9 This split also corresponded with the annual visit that was expected to be made to each branch office for the purposes of the performance evaluation. Additional visits were motivated by the need to help finalize sales with large customers.

Six variables related to branch managers and their branches in the empirical models were controlled for in testing the hypotheses. Since the home office manager's previous measurements of integration behaviour can influence his current measurement, we included the integration measurement (INTEGRATIONt−1) from the prior period. The characteristics of a branch and its manager can also influence the subjective measurement of integration behaviour. A branch manager's tenure (TENURE), measured as the number of months the manager has worked for TTE, is controlled for two reasons. First, the home office manager may assume that a branch manager with a longer tenure has good integration behaviour by virtue of his having been a manager. Second, the home office manager might focus his attention on newer branch managers to learn about them and their integration behaviour.10 To control for the turnover of 10 branch managers (TURNOVER), TURNOVER is 0 for a year in which a branch has no change in its manager and 1 for a year in which a branch has turnover of its manager and for all subsequent years for this branch.

The size (SIZE) of a branch, measured as the number of branch employees, can also influence the measurement of integration behaviour. For example, the home office manager might know more about branch managers at larger branch offices because of their importance to TTE. Branches located in provinces with higher annual growth in the sales of telecommunications terminal equipment (PROVGWTH) could be more important to TTE's future success and thus it is possible that the home office manager could know more about the managers at those branches. Alternatively, the home office manager might focus his attention on branches located in provinces with lower revenue growth because they could be risky to TTE's future and thus he may want to learn more about them. For the 1998–2003 data, we included an indicator variable to control for any effects on integration behaviour measurements due to a change in 2001 of the home office manager (MANAGER) who makes the integration behaviour measurements (0 for 1998–2000 and 1 for 2002–2003).11

Empirical Model

We used a pooled OLS regression model with year fixed effects to test the hypotheses.12 As the data cover several years with repeated observations that are associated with the same branch (in most cases the same branch manager), we included fixed effects for year (YEARDUM). That is, for the 1998 to 2003 data, four YEARDUM control variables are used (1998, 1999, 2000, and 2002). For the 2002 to 2003 data only one YEARDUM control variable is used (i.e., 0 for 2002 and 1 for 2003). For the 1998 to 2003 data model we included a manager fixed effect (MANAGER) as there was a change of sales manager during 2001. The least squares dummy variable (or fixed effect) estimate controls for the unobserved (time-invariant) heterogeneity, but it also yields biased coefficient estimates.

-

- INTEGRATIONit

-

- = branch manager i's integration behaviour in period t;

-

- SALESit (S)

-

- = log of branch i's sales in millions of Yuan in period t;

-

- EXPENSEit (E)

-

- = log of branch i's total direct operating expenses in millions of Yuan in period t;

-

- ACCRECit (A)

-

- = branch end-of-period total accounts receivable divided by mean credit sales per day in period t;

-

- CUSSATit (C)

-

- = branch customer satisfaction in period t;

-

- OBSERV-DISTit (data available 1998–2003)

-

- = negative distance between branch office i and home offices in average commercial flight time in hours. Raw values are used for additive effects and 0–1 indicator values are used for interaction effects with 0(1) for branch offices equal to or greater (less) than 1.55 hours;

-

- OBSERV-VISITit (data available 2002–2003)

-

= number of visits to each branch office with raw values for additive effects, and 0–1 indicator values for interaction effects with 0 for branch offices with less than two visits (low direct observation) and 1 for branch offices with two or more visits (high direct observation) in period t;

-

- INTEGRATIONit−1

-

- = branch manager i's integration behaviour in period t − 1;

-

- TENUREit

-

- = months that branch manager i has been employed by TTE in period t;

-

- TURNOVERit

-

- = indicator variable for turnover of branch manager i, with 0 for a year in which branch i has no turnover and 1 for the year in which branch i has turnover of its manager and for all subsequent years for branch i;

-

- SIZEit

-

- = number of employees working at branch i at the beginning of period t in period t;

-

- PROVGWTHit

-

- = annual percentage growth in sales of telecommunications terminal equipment in the province where branch i is located in period t; and

-

- MANAGER

-

- = indicator variable for the change of home office manager, with 0 for 1998–2000, and 1 for 2002–2003.

Given the multiple period and branch nature of the panel data, Huber-White robust standard errors with the cluster command were used to control for sample dependence for each branch. Whilst there were no influential observations for the 1998–2003 sample (n = 87), for the 2002–2003 sample (n = 52, 26 branch offices x two years), six influential observations were excluded that were identified based on DFITS and Cook's D-statistic, leaving a sample size of 46.13

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the variables' descriptive statistics. The variables have considerable realized variance, as assessed by their standard deviations, and ranges relative to their means. For example, INTEGRATIONt ranges from 5.95 to 21.19 and CUSSAT ranges from 28.85 to 59.60, both more than two-thirds of their respective theoretical ranges. The financial measures also have large realized ranges: SALES ranges from 0.01 to 66.86 million Yuan, EXPENSE ranges from 0.01 to 3.39 million Yuan, ACCREC ranges from 17.61 to 331.67, and OBSERV-VISIT ranges from 0 to 9 visits. All variables are normally distributed.

| Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTEGRATIONt | 12.22 | 2.89 | 5.95 | 21.19 |

| SALES | 12.81 | 11.91 | 0.01 | 66.86 |

| EXPENSE | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.01 | 3.39 |

| ACCREC | 124.29 | 74.82 | 17.61 | 331.67 |

| CUSSAT | 45.44 | 5.78 | 28.85 | 59.60 |

| OBSERV-DIST | −1.55 | 0.88 | 0.00 | −4.17 |

| OBSERV-VISIT | 2.38 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 9.00 |

| INTEGRATIONt−1 | 12.22 | 2.68 | 5.95 | 21.19 |

| TENURE | 47.15 | 22.24 | 12.00 | 93.00 |

| TURNOVER | .13 | .33 | 0 | 1.00 |

| SIZE | 4.70 | 1.84 | 1.00 | 9.00 |

| PROVGWTH | 32.00 | 130.00 | −98.90 | 1101.00 |

| MANAGER | .60 | .49 | 0 | 1.00 |

- Note:

- 1 The data consist of annual data for five years (1998–2000 and 2002–2003) with nine (1998), 10 (1999), 17 (2000), and 26 (2002 and 2003) branch offices of TTE (including a sales office that is located at the home office).

- 2 Variable measurements:

-

- INTEGRATIONit

-

- = branch manager i's integration behaviour in period t;

-

- SALESit

-

- = branch i's sales in millions of Yuan, in period t;

-

- EXPENSEit (E)

-

- = branch i's total direct operating expenses in millions of Yuan in period t;

-

- ACCRECit (A)

-

- = branch end-of-period total accounts receivable divided by mean credit sales per day in period t;

-

- CUSSATit (C)

-

- = branch customer satisfaction in period t;

-

- OBSERV-DISTit (available 1998–2003)

-

- = negative distance between branch office i and home offices in average commercial flight time in hours, with raw values for additive effects and 0–1 indicator values for interaction effects with 0(1) for branch offices equal to or greater (less) than 1.55 hours;

-

- OBSERV-VISITit (available 2002–2003)

-

- = number of visits to each branch office with raw values for additive effects, and 0–1 indicator values for interaction effects with 0 for branch offices with less than two visits (low direct observation) and 1 for branch offices with two or more visits (high direct observation) in period t;

-

- INTEGRATIONit−1

-

- = branch manager i's integration behaviour in period t − 1;

-

- TENUREit

-

- = months that branch manager i has been employed by TTE in period t;

-

- TURNOVERit

-

- = indicator variable for turnover of branch manager i, with 0 for a year in which branch i has no turnover and 1 for the year in which branch i has manager turnover and for all subsequent years for branch i;

-

- SIZEit

-

- = number of employees working at branch i at the beginning of period t;

-

- PROVGWTHit

-

- = annual percentage growth in sales of telecommunication terminal equipment in the province where branch i is located in period t;

-

- MANAGER

-

- = indicator variable for the change of home office manager, with 0 for 1998–2000, and 1 for 2002–2003.

-

Table 2 presents Pearson coefficients for the variables. INTEGRATIONt has significant (p < .10) positive correlations with ACCREC, CUSSAT, TURNOVER (p < 0.05), and SIZE. Six correlations between independent variables are significant at p < .10. In particular, SALES is significantly correlated with EXPENSE, ACCREC, and CUSTOMER. EXPENSE is correlated with OBSERV-DIST and OBSERV-VISIT (p < .05). The correlation between OBSERV-DIST and OBSERV-VISIT is –0.39 (p < .01) indicating that the OBSERV-DIST variable is a reasonable proxy for direct observation in terms of the number of visits to a branch by the home office manager. Among the control variables, the correlation between SIZE and each of TURNOVER (p < .01) and MANAGER (p < .05) is significant. The correlation between MANAGER and each of TENURE (p < .05) and TURNOVER (p < .05) is significant. The correlation between SIZE and INTEGRATIONt−1 (p < .05) is significant.14 The lack of highly significant correlations reduces the probability of a significant multicollinearity problem.

| INTEGRAT | SALES | EXPENSE | ACCREC | CUSSAT | OBSERV | OBSERV | INTEGRAT | TENURE | TURN | SIZE | PROV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -IONt | -DIST | -VISIT | -IONt−1 | OVER | GWTH | |||||||

| SALES | 0.06 | |||||||||||

| EXPENSE | 0.02 | 0.55‡ | ||||||||||

| ACCREC | 0.22† | −0.26† | −0.06 | |||||||||

| CUSSAT | 0.31‡ | 0.21† | 0.21* | 0.03 | ||||||||

| OBSERV-DIST | −0.10 | 0.19* | 0.23† | −0.05 | −0.04 | |||||||

| OBSERV-VISIT | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.37‡ | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.39‡ | ||||||

| INTEGRATIONt−1 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.26† | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |||||

| TENURE | 0.00 | 0.22† | 0.40‡ | 0.19* | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.28† | −0.04 | ||||

| TURNOVER | 0.27† | 0.15 | 0.10 | −0.12 | 0.20* | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.09 | −0.09 | |||

| SIZE | 0.24† | 0.44‡ | 0.39‡ | −0.22† | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.28† | 0.19* | 0.08 | 0.30‡ | ||

| PROVGWTH | −0.03 | −0.14 | 0.01 | 0.28‡ | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.15 | −0.14 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.17 | |

| MANAGER3 | −0.00 | −0.07 | 0.18* | 0.44‡ | −0.13 | −0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.57‡ | −0.28‡ | −0.29‡ | 0.00 |

- Notes:

- 1 Significance levels: * p < 0.10, † p < 0.05, and ‡ p < 0.01 (two-tail test).

- 2 See Table 1 for how the variables were measured. OBSERV-VISIT correlations are shown for the 2002–2003 period only.

Hypothesis Tests

The two regression models in Table 3 include the independent and control variables as well as the interaction terms. The adjusted R2s range from .12 (p < .05) and .33 (p < .01) and are significantly (p < .05) higher than the adjusted R′2s of the main-effects models, which includes the independent and control variables, but not the interaction terms. Multicollinearity is not a problem, as evidenced by the largest VIF of 6.15 and the largest condition index value of 33.47, which are within the accepted limits (Belsley, 1991). The residuals of the model are normally distributed.

| INTEGRATIONit = B0 + B1 SALESit + B2 EXPENSEit + B3 ACCRECit + B4 CUSSATit + B5 OBSERVit + B6 INTEGRATIONit−1 + B7 TENUREit + B8TURNOVERit + B9 SIZEit + B10 PROVGWTHit + B11 MANAGER + B12 OBSERV *S + B13 OBSERV *E + B14 OBSERV *A + B15 OBSERV *C + εit, | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Predicted sign | OBSERV-DISTit | OBSERV-VISITit | ||

| 1998–2003 | 2002–2003 | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| CONSTANT |

0.37 (0.10) |

−2.79 (−0.68) |

5.31 (1.09) |

10.71† (2.17) |

|

| SALES (S) |

0.16 (0.69) |

−0.16 (−0.64) |

−0.05 (−0.22) |

0.89 (1.64) |

|

| EXPENSE (E) |

−0.61* (−1.79) |

−0.04 (−0.08) |

0.22 (0.49) |

0.12 (0.28) |

|

| ACCREC (A) |

0.11* (1.95) |

0.01 (1.60) |

0.00 (0.30) |

0.01 (1.01) |

|

| CUSSAT (C) |

0.14‡ (2.80) |

0.25‡ (3.53) |

0.18† (2.10) |

−0.02 (−0.32) |

|

| OBSERV |

0.07 (0.25) |

0.14 (0.46) |

0.17 (1.00) |

0.32‡ (3.00) |

|

| INTEGRATIONt−1 |

0.09 (0.81) |

0.05 (0.38) |

0.02 (0.16) |

0.11 (0.82) |

|

| TENURE |

−0.01 (−0.70) |

−0.01 (−0.98) |

−0.04* (−1.68) |

−0.05† (−2.38) |

|

| TURNOVER |

1.28 (1.13) |

1.42 (1.28) |

|||

| SIZE |

0.41 (1.64) |

0.34 (1.30) |

0.06 (0.24) |

0.01 (0.03) |

|

| PROVGWTH |

−0.11 (−0.70) |

−0.25 (−1.30) |

−0.05 (−0.56) |

−0.09 (−0.90) |

|

| MANAGER |

0.85 (1.17) |

1.09 (1.63) |

|||

| OBSERVx SALES | H1a– |

−1.42‡ (−2.88) |

−1.72† (−2.25) |

||

| OBSERV x EXPENSE | H1b+ |

3.21‡ (3.09) |

0.20 (0.34) |

||

| OBSERVx ACCREC | H1c+ |

0.51 (0.75) |

−0.57 (−1.01) |

||

| OBSERV x CUSSAT | H2+ |

1.09† (2.19) |

2.34‡ (4.43) |

||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.30 | |

|

P = N = |

0.01 87 |

0.00 87 |

0.03 46 |

0.00 46 |

|

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| MANAGER Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

- Notes:

- 1 Significance levels: * p < 0.10, † p < 0.05, and ‡ p < 0.01 (two-tail test). The relevant t-statistics in brackets were computed using Huber-White robust standard errors. The data for Model 1 represent a year fixed effects pooled sample of 88 for 1998–2000 (n = 36) and 2002–2003 (n = 52) less one for the lagged variable for integration (INTEGRATIONt−1). The data for Model 2 represent a year fixed effects pooled sample for 2002–2003 (n = 52). Six observations were removed from the Model 2 based on the DFITs test statistic.

- 2 The models include control variables (not shown) for year to control for any effects on integration behaviour measurements. That is, for the 1998 to 2003 data, four YEARDUM control variables are used. For the 2002–2003 data only one YEARDUM control variable is used (i.e., 0 for 2002 and 1 for 2003).

- 3 Variable measurements:

-

- INTEGRATIONit

-

- = branch manager i's integration behaviour in period t;

-

- SALESit (S)

-

- = log of branch i's sales in millions of Yuan, in period t;

-

- EXPENSEit (E)

-

- = log of branch i's total direct operating expenses in millions of Yuan in period t;

-

- ACCRECit (A)

-

- = branch end-of-period total accounts receivable divided by mean credit sales per day in period t;

-

- CUSSATit (C)

-

- = branch customer satisfaction in period t;

-

- OBSERV-DISTit (available 1998–2003)

-

- = negative distance between branch office i and home offices in average commercial flight time in hours, with raw values used for additive effects and 0–1 indicator values used for interaction effects with 0(1) for branch offices equal to or greater (less) than 1.55 hours.

-

- OBSERV-VISITit (available 2002–2003)

-

- = number of visits to each branch office with raw values for additive effects, and 0–1 indicator values for interaction effects, with 0 for less than two visits (low direct observation), and 1 for more than two visits (high direct observation) in period t;

-

- INTEGRATIONit−1

-

- = branch manager i's integration behaviour in period t − 1;

-

- TENUREit

-

- = months that branch manager i has been employed by TTE in period t;

-

- TURNOVERit

-

- = indicator variable for turnover of branch manager i, with 0 for a year in which branch i has no turnover and 1 for the year in which branch i has manager turnover and for all subsequent years for branch i;

-

- SIZEit

-

- = number of employees working at branch i at the beginning of period t;

-

- PROVGWTHit

-

- = annual percentage growth in sales of telecommunications terminal equipment in province where branch i is located in period t;

-

- MANAGER (Model 1)

-

- = indicator variable for change of home office manager, with 0 for 1998–2000, and 1 for 2002–2003.

-

Main Effects Hypotheses—Financial and Nonfinancial Performance Measures

H1 predicts that the level of the integration behaviour performance measure will be positively related to the level of the sales measure and negatively related to the levels of the expense and accounts receivable measures, and that the absolute magnitudes of these bivariate relations will decrease with the home office manager's direct observation of a branch manager.

For the sales measure, the significant (p < .05) negative betas for the SALES by OBSERV-DIST (p < .01; Model 1) and SALES by OBSERV-VISIT (p < .05; Model 2) interactions provides support for H1. For the expense measure, the significant (p < .01) positive sign of the beta for the EXPENSE by OBSREV-DIST interaction (Model 1) provides support for H1. However, the beta for the EXPENSE by OBSERV-VISIT is not significant (p > .10), thus providing mixed support for H1. Finally, for the accounts receivable measure, the beta for ACCREC by OBSREV-DIST (Model 1) and ACCREC by OBSREV-VISIT (Model 2) interactions are not significant (p = 0.50 and .34) for each of the interaction models, which does not provide support for H1.

H2 predicts that the positive influence of the level of the customer satisfaction measure on the level of the integration behaviour measure will increase as direct observation increases. The result of significant positive betas for the CUSSAT by OBSERV-DIST (p < .05; Model 1) and CUSSAT by OBSERV-VISIT (p < 0.01; Model 2) interactions provide support for H2.

Sensitivity Tests

The sensitivity of the results was tested in several ways. First, the results were qualitatively the same whether none, all, or any one of the six control variables was included. Second, as observability was expected to be related to both the reliability of the customer satisfaction measure and the level of integration behaviour, this raised the potential for a correlated omitted variable problem, which will bias the results in favour of a larger coefficient on the customer satisfaction measure for closer branch offices. When we re-ran the models with a measure of customer satisfaction that was orthogonal to the level of observability (e.g., the residual from a model in which customer satisfaction was regressed separately on each of the three observability proxies in their continuous form), the significance of all of the hypothesized estimates was qualitatively unchanged. Third, since the data are comprised of the same branches for multiple years, two observations have the median value (1.55 hours). The result of testing the hypothesis is qualitatively unchanged when these two observations are excluded, included in the low OBSERV level (as reported in Table 3), or included in the high OBSERV level.

Sensitivity Tests for the Effect of Branch Manager Experience and Home Office Manager Knowledge

We controlled for the tenure of the branch manager as this could affect the level of experience and/or knowledge that the home office manager had of him. It is possible that the level of experience of the branch manager might affect the subjective performance measurement rating. For example, less experienced managers might be subject to more frequent visits or be located closer to the head office. The home office manager might want to locate less experienced managers at branches nearer to the home office to observe and monitor their integration behaviour. We found that the correlation between TENURE and DISTANCE was –.09 and not significant (p = 0.42).

Sensitivity tests for the effect of branch office manager turnover

Branch office manager turnover could have affected the ratings. In our sample, nine branch office managers changed offices in 2000 and one changed offices in 2001. We controlled for the effects of turnover in two ways. First, we added a manager branch office tenure variable (number of months with the branch office). When this variable was included in Model 2 (either with or without the firm-level tenure variable), the manager branch office tenure variable (both main-effect and two-way interactions with the performance measures) was not significant (p < 0.20) and the qualitative significance of the four hypothesized two-way interaction estimates were unchanged. Second, we re-ran Model 2 without the 10 turnover cases and found that the qualitative significance of the interaction effects was unchanged.

Sensitivity tests for the effect of change in home-office manager

The change in home office manager who made the integration behaviour ratings was controlled for through the use of an indicator variable (MANAGER: 0 for 1998–2000 and 1 for 2002–2003). We tested the interaction of this indicator variable with each of the four performance measures and found that one (MANAGER *ACCREC) of the four interactions was significant (p < .10) and the qualitative significance of the four hypothesized interactions were unchanged.

Discussion and Conclusion

Accounting research investigates factors that influence the choice and use of financial and nonfinancial performance measures, but accounting research on how people subjectively measure performance is rare. Our paper contributes to the accounting literature by providing theory-based archival evidence on how the influence of performance measures on subjective performance measurement is likely to depend on the home office manager's verification of financial and nonfinancial measures of sales branch managers' performance.

The results are consistent with some of the hypotheses. As hypothesized, as the home office manager's direct observation increases, the results indicate that the sales measure and maybe the expense measure have a decreasing influence on the level of the integration behaviour measure. In contrast, as direct observation increases, the customer satisfaction measure has an increasing influence on the level of the integration behaviour measure. The results are consistent with the analytical literature (Baker et al., 1994; Baiman and Rajan, 1995).

In reviewing the partial results of expenses and accounting receivables for H1, we offer the following explanations. Expenses comprised a small portion of the incentive scheme (5%) and are connected with the level of sales, for which we found consistent results. For accounts receivables however, we did not find significant results for the prediction that as direct observation increases, the accounts receivable measure will have a decreasing influence on the level of the integration behaviour measure. Several plausible reasons are offered for this result based on the notion that accounts receivable are influenced in part by the quality of sales made and level of customer service in the prior period, and the cash collection effort made in the current period. First, the level of accounts receivable is a lag indicator of past actions and efforts of the branch sales managers. That is, accounts receivable is a reflection of the quality of the sales made in the prior period and the treatment of customers in the prior period. Second, the controllability of the collection of accounts receivable might not be constant or consistent as sales and expenses. For example, in return sales, prior accounts receivable become a bargaining point, with as much as 20% of the accounts receivable being forfeited in order to make new sales. Some of the accounts receivable were outstanding by over 300 days. Thus, accounts receivable are subject to discretion that may be difficult for a remote office to control.

This paper has limitations, including its small sample size and the use of data from only one firm, which may reduce the empirical generalizability of the results to other settings. The small sample size also limits the robustness tests that can be performed, for example, to reduce the threat of distortion from time-series collinearity on the results. Another possible limitation is measurement error. For example, direct observation could be measured as the length (e.g., number of hours) of branch office and branch customer visits by the home office manager. However, this data were not available to us. Whilst we were only able to fully test the models using distance data as a negative proxy for direct observation, we did show similar findings for the second sales manager using the number of visits as a proxy for direct observation. Although the correlation between the two proxies is –0.39, being able to have visit data for the years 1998–2000 would help to strengthen the generalizability of our findings. Finally, the hypotheses were tested using the aggregate integration measure because we did not have access to the data from which it was calculated.

Despite these potential limitations, our paper identifies a new area for accounting research—subjective performance measurement and variables such as performance measures that affect these measurements. As accounting increasingly includes performance measures that involve subjective measurement, research investigating how measurers make subjective performance measurements and the factors that affect these measurements will be increasingly valuable. Besides the effect of informational properties associated with direct observation and type of performance measures to the measurer, subjective performance measurement can be influenced by non-economic factors such as cognitive bias, favouritism, and fairness (Wherry and Bartlett 1982; Prendergast and Topel 1993, 1996; Moers 2005; Bol and Smith, 2011). Subjective performance measurement can also be influenced by the measurers' characteristics, such as their ability, knowledge, and motivation (Birnberg et al., 2007), and by the characteristics of the measures (e.g., precision, sensitivity) and the measurements (e.g., degree and type of subjectivity). In closing, our paper identifies opportunities for interesting and valuable research on subjective performance measurement related to accounting performance measures.

Footnotes

Appendix A

-

Why did you include the integration behaviour measure in the performance evaluation plan? Give some examples.

- (a)

Encourage communication and teamwork:

-

‘To encourage team spirit among different branch offices, which the sales numbers would not be able to do’. (Home office manager)

-

‘The general manager wants an element of control over the home office relationship with the branch manager and the subjective element is the mechanism used for this purpose’. (CFO-VP finance)

-

- (b)

Encourage managerial skill development:

-

‘To encourage managers to be proactive in improving not only their sales capabilities but also their management skills’. (Home office manager)

-

‘We want people to be able to see everything. They should not just be able to make sales, but should be able to motivate people, organize things strategically, put down their thoughts onto paper, think logically, and express themselves in a coherent fashion. Thus, we ask our branch managers to see who has this potential, who could be a leader in the future. Thus, the subjective measure matters to skill development in addition to motivating sales. The purpose is to broaden the skills of the manager into a well-rounded team leader’. (CFO-VP finance)

-

- (a)

-

What behaviour did senior management want to avoid by including the integration behaviour measure? Give some examples.

- (a)

Not sharing private information and poor communication skills:

-

‘When the managers didn't reveal their private information about the local markets’. (Home office manager)

-

‘Even when they did reveal [information], their communication skills were lacking. As a result, the home office didn't have a clear picture about the market. This, in turn, increased the difficulty of scheduling and planning’. (Home office manager)

-

‘The integration behaviour measurement is also influenced by the frequency of communication. Maybe this gentleman has a better relationship or ability to communicate with his superior. The branch manager lets his superior know everything he did which is not reflected by the incentive formula, while the other gentleman who tends to be quieter and does not know how to communicate what he did, which is not reflected by the formula. This latter gentleman receives a lower integration behaviour measurement’. (CFO-VP finance)

-

- (b)

Short-term behaviour:

-

‘Some managers only paid attention to the current year sales even if doing so might damage future sales. A typical example of this is that a manager picks a huge bonus because of the sales number but leaves the next year with a lot of outstanding accounts receivable’. (Home office manager)

-

‘To avoid these types of behaviours, the home office had to implement the integration behaviour measure to complement the sales measures’. (Home office manager)

-

- (a)

-

What type of accounting system have you installed and how reliable is it across the branch offices? Give some examples.

- ‘We have an internal control system that was designed by a large audit firm. In 2000, we engaged the same audit firm to conduct annual audits in readiness for public listing in 2002. We installed an Oracle enterprise management system in 2001 and we are able to determine its reliability through month end closing and six monthly internal audits’. (CFO-VP finance)

- ‘We have monthly closing and only a few months would take longer than expected—due to waiting to get customers' confirmation of invoices so that revenue can be recognized. Furthermore, there were few instances of restatements of past monthly sales, which gave assurance as to the reliability of the system’. (CFO-VP finance)

-

To what extent did the home office manager believe that the accounting performance measures produced by the accounting system were reliable across the branch offices?

- ‘The home office manager believes that the branch financial measures are reliable because of my many conversations with him about the high quality of TTE's accountants, accounting, internal controls, and external and internal audits, which do not vary across TTE's branches. The home office manager was also involved in the six-monthly internal audits’. (CFO-VP finance)

Appendix B

-

How does the home-office manager observe the branch managers' integration behaviour in order to come up the measurement?

- (a)

When you sit down and begin to measure the manager's integration behaviour, do you spend a lot of time thinking about each aspect of integration behaviour? Are the sales figures or other objective criteria already in your mind or do you look these figures up and then use them for your measurement? Or would you look for sales figures for reference when you're not quite sure about one aspect of integration behaviour?

-

‘Yes, I will. But I will not deliberately go to find the sales numbers for reference. Instead, I use my memory. For branches that have a good sales record, I remember much clearer. I won't clearly categorize them by numbers but I get a sense of approximately which category each manager should belong to. But the measurements done by the branch manager are greatly influenced by whether there are any customer complaints from the branch to the head office, whether there's any message from the head office that a branch office failed to respond to or act upon or whether there's serious conflict between branch employees. If so, that branch won't get a high score. In contrast, if the employees at a branch office support each other, that branch will get a higher score’. (Home office manager)

-

- (b)

How do you know whether the employees at each branch support each other?

-

‘I visit every branch office, conduct face-to-face interviews and talk with the branch employees and customers. This is very important in the measurement’. (Home office manager)

-

- (a)

-

Do you have some notes or records of your interviews?

- ‘No, it's just in my head. Some foreign firms do have working notes. But as we sort of switch from one business to another and we basically know nothing about the new business, we are not used to keeping records’. (Home office manager)

- ‘My secretary will send me a form which I will fill in and she will take it back to the office and enter all the data into an Excel file. I will then take the Excel file and check whether it is consistent with the expectations in my mind. I do some adjustments if it is not consistent’. (Home office manager)

- ‘And every time before I finalize the measurement, I send the form to the CFO and the CEO to see whether there's any chance that I've made a mistake’. (Home office manager)

- ‘The finalizing of the measurement (of integration behaviour, which includes gathering all of the end-of-period information and discussions with other home office managers) usually takes two to three days’. (Home office manager)

-

How does the home office manager approach the task of comparing the branch managers on integration behaviour?

- (a)

When you compare the branches, do you compare the offices as a whole (e.g., holistically) or do you compare different offices under each integration behaviour item? Do you compare each of the items or do you make a consolidated (holistic) comparison? Is it holistic or an item-by-item comparison?

-

‘It's a column (holistic) approach. It is very difficult to horizontally evaluate the branch managers item by item since, for example, if one of them may already be very good in writing but is still better in leadership. You may not be able to give the managers a score without reference to other manager attributes’. (Home office manager)

-

- (b)

So how much influence do the items have on one person to each other? For example, a manager might be extremely good at sales but not good at other things at all.

-

‘Yeah, so we gave him a passing grade so as not to piss him off but certainly not to place him on the top of the list. We just get somebody, for example, to write a monthly report for him. This guy is quite old and we all know that his leadership style is not going anywhere. But when we see some young guy with good sales ability and potential to become manager, we try to train and change them’. (Home office manager)

-

- (a)

-

What is your confidence in making as accurate (unbiased) a measurement as possible?

- (a)

For the branch offices that you visit more, do you believe your judgment is more accurate?

-

‘Actually, I'm quite confident for every measurement I do for the branch managers. Most of the time I don't worry much about the accuracy of my measurement since, you know, sales is a business in which you try to keep the best people and have them work as hard as possible’. (Home office manager)

-

- (b)

How did you feel when you took over in 2001? In 2002, did you, for the first time, have to give a specific score to each manager?

-

‘I tried to learn about performance measurement. I read several books and looked at the current system, trying to figure out what needed to be changed. It took me two to three months for the whole system to come out’. (Home office manager)

-

- (a)

-

How much confidence do you have in the reliability of the sales and other financial numbers across the branch offices?

- ‘I have confidence in the sales numbers provided by our accounting system and my confidence level does not change from branch to branch. First, I was the one who approved every single sales contract. Second, I was the research and development director before I became home office manager and I have a good knowledge of product costs and have had confidence in our accounting system in providing such data’. (Home office manager)