Overwork: A Review of the Literature and Importance to Management Accounting Research*

Accepted by Leslie Berger. This paper is based on my dissertation at the University of Waterloo. Many thanks to Leslie Berger (associate editor) and two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful suggestions. I gratefully acknowledge the support and guidance provided by my dissertation committee co-chairs, Tim Bauer and Adam Presslee, as well as my committee members, Alan Webb, Krista Fiolleau, Janet Boekhorst, and Flora Zhou. I thank the CPA Ontario Centre for Sustainability Reporting and Performance Management (CSPM) and the DeGroote School of Business at McMaster University for their generous funding. I thank Ismat Jahan and Saaniyah Chitamun for their excellent research assistance work.

ABSTRACT

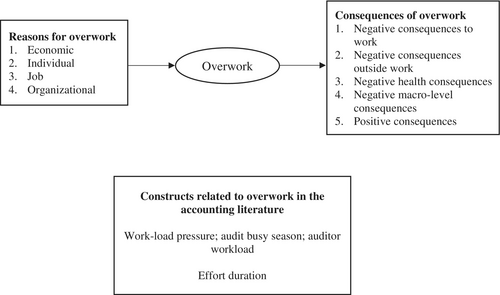

enIn this paper, I examine the literature on overwork, and I discuss its significance to the management accounting literature. Overwork, or working long hours, is a prevalent phenomenon, particularly among professional workers. Despite its pervasiveness, overwork has seldom been addressed in the accounting literature or studied as a distinct construct in managerial accounting research. Consequently, there is limited understanding of the management controls that contribute to overwork and the consequences of overwork in a management accounting context. This is despite overwork directly relating to an assumption in the management accounting literature that management controls are needed to motivate otherwise effort-averse employees. In this paper, the existing literature on employee overwork, primarily sourced from outside of accounting, is systematically reviewed and categorized into reasons for overwork and consequences of overwork. I discuss reasons at the economic, individual, job, and organization levels that are proposed as antecedents of overwork in the literature. I also find that there are negative consequences to overwork in the work domain as well as outside of work and to employee health, in addition to important macro-level consequences. Additionally, some relevant findings from the accounting literature are discussed. This paper also identifies significant gaps in the overwork literature from a management accounting perspective and discusses future research opportunities.

RÉSUMÉ

frSurmenage professionnel : examen de la littérature et importance au sein de la recherche en comptabilité de gestion

Dans la présente étude, j'examine la littérature sur le surmenage professionnel et discute de son importance dans la littérature sur la comptabilité de gestion. Le surmenage professionnel (le fait de travailler de longues heures) est un phénomène répandu, en particulier chez les travailleurs professionnels. Malgré sa prévalence, il n'a que rarement été abordé dans la littérature comptable ou étudié en tant que construct distinct dans le contexte de la recherche en comptabilité de gestion. Par conséquent, les contrôles de gestion qui contribuent au surmenage et les conséquences du surmenage dans un tel contexte sont mal compris, et ce, même si le surmenage est directement associé à une hypothèse présente dans la littérature sur la comptabilité de gestion selon laquelle les contrôles de gestion sont nécessaires pour motiver les employés qui, autrement, seraient réticents à l'effort. La présente étude passe en revue la littérature sur le surmenage chez les employés, principalement hors du domaine de la comptabilité, et établit un classement des éléments menant au surmenage professionnel et de ses conséquences. Je me penche sur les éléments à l'échelle économique, individuelle, professionnelle et organisationnelle que la littérature propose comme facteurs menant au surmenage. J'établis également que le surmenage a des conséquences négatives tant dans le monde du travail qu'à l'extérieur, ainsi que sur la santé des employés, en plus d'importantes conséquences générales. En outre, je discute de certaines observations pertinentes tirées de la littérature comptable. Cette étude relève aussi d'importantes lacunes dans la littérature sur le surmenage selon une perspective de comptabilité de gestion et se penche sur les possibilités de recherche à venir.

INTRODUCTION

In this paper, I review the literature on employees' long working hours, hereby labeled as “employee overwork” or “overwork” (e.g., Cha & Weeden, 2014). Employee overwork can be more concretely defined as employees working beyond contractual, statutory, or internal firm policy standard working time, for no immediate additional monetary gain (Consultancy.eu, n.d.; Feldman, 2002; Ladva and Andrew, 2014; Mokhtar, 2023). Examining overwork within an accounting context, especially from a management accounting perspective, is important. Management accounting research is largely interested in how managerial controls can be used to motivate employees, assuming employees are naturally effort-averse (Sprinkle, 2003; Van der Stede, 2015). In contrast, in situations where overwork is prevalent, employees work long hours for no immediate additional compensation, and they often believe their long work hours are self-inflicted (Blagoev et al., 2018; Empson, 2018; Kellogg, 2009; Ladva & Andrew, 2014; Lewis, 2003; Lupu & Empson, 2015; Michel, 2011). Thus, the management controls that lead to overwork seem to do so in indirect ways that are not readily apparent to employees. Yet this literature review reveals that there is little research examining the management controls that lead to this overwork and the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon, with two exceptions (Ladva & Andrew, 2014; Mokhtar, 2023). Even more generally, there is limited research in the accounting literature examining overwork as a distinct construct.

Importantly, as often discussed in the popular press, employees working long hours is a commonplace phenomenon (Hewlett & Luce, 2006; Karaian & Sorkin, 2021). This is exemplified in a 2008 Harvard Business School survey that found that 94% of surveyed professionals work more than 50 h a week (Perlow & Porter, 2009). A more recent 2019 survey conducted in the United Kingdom found that 91% of professionals at least sometimes work more than their contracted hours (with 31% of respondents always working more than contracted hours) and that 90% of those professionals receive no form of additional compensation for working longer than their contracted hours (Morgan McKinley, 2019). Although long working hours has been a long-standing issue, the situation was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Beheshti, 2021; Vershbow, 2021). For example, a year into the pandemic, analysts at Goldman Sachs, who were working an average of 95 h a week, threatened to quit their jobs unless their conditions improved (Reuters Staff, 2021).

To provide a better understanding of overwork and the importance of studying overwork in the accounting literature, I provide a literature review of overwork as it has so far been studied. Overwork has primarily been studied outside the accounting literature. Thus, I expand on the broader organizational behavior, human resource management, economics, and psychology literatures that study proposed reasons for employee overwork. I then discuss the consequences of overwork documented in these literatures to expand on the importance of understanding overwork in firms. I also discuss constructs related to overwork in the accounting literature, namely audit workload and effort duration, to underscore its importance to accounting researchers.

Overall, I discuss various factors that have been proposed to lead employees to overwork, namely economic, individual, job, and organizational factors (Feldman, 2002). I further find that, although firms often place a high value on overwork (Gicheva, 2013), much research highlights its adverse effects, such as negative outcomes at work and at the macro level, as well as in workers' personal lives and health. My paper also explores gaps in the existing literature on overwork and suggests avenues for future research, particularly from a management accounting perspective. Among other insights, my findings suggest that the management accounting literature can benefit greatly from incorporating overwork as a management control construct, such as by examining management controls that cause overwork, as well as examining management control consequences of overwork. I also suggest examining management control factors that cause overwork to have more negative than positive firm consequences.

My literature review makes important contributions to the accounting literature and to practice. First, as is frequently highlighted in the popular press, the phenomenon of employees working long hours is prevalent, and it has become increasingly commonplace since the COVID-19 pandemic (Beheshti, 2021; Hewlett & Luce, 2006; Karaian & Sorkin, 2021; Vershbow, 2021). Consequently, overwork stands as a significant phenomenon that managers should continue to examine in their firms and researchers should more deeply understand. My review synthesizes our existing knowledge on overwork and provides a source for researchers and managers to understand the environment and trade-offs related to overwork.

Second, I synthesize existing research on overwork to allow for gaps in the literature to be more apparent for future research, and I do so with a view to contributing to the management accounting literature. As far as I am aware, this has not previously been done in the literature. Finally, I also contribute to bringing the construct of overwork to the forefront as a management accounting issue, and I discuss important gaps in our understanding and future opportunities in management accounting in the study of overwork. Importantly, there is little empirical evidence that examines management controls that lead to overwork and that examines a direct causal relationship between management controls and overwork (Mokhtar, 2023). There is also little empirical evidence that examines the consequences of overwork on important management control outcomes, such as employee honesty and fairness perceptions. Thus, my review allows management accounting researchers to gain a more complete understanding of overwork as it has been studied across different fields and to better position their research within this literature.

This paper is organized as follows. I start by describing the method I use to review the literature on overwork in Section 2. I then present the articles I find related to overwork, organized into proposed reasons for overwork, consequences of overwork, and overwork in the accounting literature in Section 3. In Section 4, I discuss opportunities for future research in overwork in the management accounting space. Finally, in Section 5, I conclude.

A conceptual model of the overwork findings in this paper is shown in Figure 1.

METHOD

To provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on overwork, I adopt a systematic approach to reviewing the literature.1 In this way, I am able to synthesize and develop insights on the current state of the literature as well as suggest opportunities for future research (Massaro et al., 2016). I work with a specific aim (Massaro et al., 2016): to examine the research and findings on overwork in the literature. I follow a five-step approach in conducting my review. I first start with a keyword search of the literature. I do a comprehensive search of Google Scholar, using the following keywords: “overwork,” “employee overtime,” and “working time.”2 I compile a list of relevant papers and limit them to those that are clearly related to the concept of overwork as defined above. Second, I do a separate keyword search in accounting journals, by limiting my search results to accounting journals in Google Scholar and using the same keywords noted previously and also searching for “effort duration.” This allows me to ensure that I include accounting papers that are relevant to, although do not directly examine, overwork; from these, I include some audit papers that examine auditor workload, and I include some managerial accounting papers that examine effort duration. I do not include all papers examining auditor workload and effort duration, as the purpose of including these papers is to bring the overwork construct closer to an accounting audience rather than to do a complete literature review on these constructs. I do not limit my article search to specific years, given that, as far as I am aware, there has been no similar literature review done prior to this one. As a third step, a research assistant conducts a comprehensive search of the scholarly databases for these keywords: “overwork,” “working hours,” “working time,” “work time,” “long working hours,” “long hours,” “long work time,” “effort duration,” and “work-life balance.”3 Although a search of the keywords was done in Step 1, doing it again in Step 3 helps ensure that I did not miss important papers about overwork in Step 1. Once again, I limit the articles that I include in this literature review to those that are clearly related to the concept of overwork as defined above, rather than to constructs such as flexible work hours or compressed work weeks. As a fourth step, I filter all articles by journal impact factor (“Web of Science” impact factor), limiting the articles included in this literature review to those published in journals with a 5-year impact factor of 2.0 and above. This is a subjectively chosen impact factor cutoff that nevertheless allows me to review a vast number of articles in relatively good quality journals. I also include two dissertation studies and an institutional report that are directly relevant to overwork, as they enhance the findings of this review (Massaro et al., 2016). As a fifth step, I organize my articles into the following categories: (1) proposed reasons for overwork, which are further categorized, for ease of classification, into economic, individual, job, and organizational factors (Feldman, 2002); (2) consequences of overwork, which are further classified as negative consequences to work, negative consequences outside of work, negative health consequences, negative macro-level consequences, and positive consequences; and (3) overwork in the accounting literature. These categories allow me to provide an organized view of the overwork literature, as well as discuss how overwork relates to the accounting literature. Thus, any articles found in my literature search that are not directly related to these categories are excluded, as they would not fit into the overall framework of this literature review. Note that, although I discuss some articles related to the health consequences of overwork, I do not include all health articles that I find in the overwork space, as these comprise a big literature that is not directly relevant to accounting research.

The articles that I review in this paper are summarized in Tables 1–3.

| Panel A: Proposed reasons for overwork | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper | Method | Setting | Location | Category in paper | Type | Field |

| Feldman (2002) | Theoretical model | — | — | Economic, individual, job and organizational | Journal article | Human resource management |

| Golden (2009) | Theoretical model and historical trend analysis | — | — | Economic | Journal article | Business and economics |

| Ng and Feldman (2008) | Meta-analysis | — | Multiple (mainly USA) | Individual | Journal article | Organizational behavior |

| Frei and Grund (2020) | Survey | Doctoral students and doctoral graduates | Germany | Individual | Journal article | Human resource management |

| Major et al. (2002) | Survey | Fortune 500 company | USA | Individual | Journal article | Psychology |

| Wallace (1997) | Survey | Active members of the legal profession | Canada | Individual | Journal article | Psychology |

| Brett and Stroh (2003) | Survey | Alumni of Midwest graduate school of business | USA | Individual | Journal article | Psychology |

| Kuroda and Yamamoto (2019) | Employer-employee matched panel survey | Firms with >100 employees | Japan | Individual | Journal article | Psychology |

| Wick (2020) | Experimental | Generic | USA and Canada | Job | Journal article | Accounting |

| Kodz et al. (1998) | Field study | Twelve leading UK employers | UK | Job | Institutional report | Employment |

| Landers et al. (1996) | Analytical model and survey | Two major law firms in large Northeastern city | USA | Organizational | Journal article | Economics |

| Barlevy and Neal (2019) | Analytical model and survey | Law firms | USA | Organizational | Journal article | Economics |

| Sousa-Poza and Ziegler (2003) | Analytical model and survey | Individuals with contractual working times >35 h per week | Switzerland | Organizational | Journal article | Economics |

| Afota et al. (2019) | Theoretical model | — | — | Organizational | Journal article | Human resource management |

| Maume and Bellas (2001) | Survey | Ohio working families | USA | Organizational | Journal article | Psychology |

| Eastman (1998) | Survey | MBA students | USA | Organizational | Journal article | Industrial relations and labor |

| Lupu and Empson (2015) | Interview | Accounting firm | France | Organizational | Journal article | Accounting |

| Peticca-Harris et al. (2015) | Qualitative analysis | Video game developers | USA | Organizational | Journal article | Management |

| Kang et al. (2017) | Theoretical model | — | Asia | Organizational | Journal article | Management |

| Ladva and Andrew (2014) | Interview | Large multinational accounting firms | Australia | Organizational | Journal article | accounting |

| Mokhtar (2023) | Experimental | Generic | USA | Managerial accounting | Overwork | Dissertation |

| Panel B: Consequences of overwork | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper | Method | Setting | Location | Category | Type | Field |

| Golden (2012) | Synthesis | — | — | Negative consequences to work | Institutional report | Labor |

| Pencavel (2015) | Archival | Munition workers during the First World War | UK | Negative consequences to work | Journal article | Economics |

| Steinmetz et al. (2014) | Survey/archival | Healthcare employees | Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands | Negative consequences to work | Journal article | Human resource management |

| Mazzetti et al. (2014) | Survey | Dutch employees | The Netherlands | Negative consequences to work | Journal article | Psychology |

| Mazzetti et al. (2016) | Survey | Italian employees | Italy | Negative consequences to work | Journal article | Psychology |

| Shafer et al. (2018) | Archival | IT workers | USA | Negative consequences outside work | Journal article | Sociology |

| Major et al. (2002) | Survey | Fortune 500 company | USA | Negative consequences outside work | Journal article | Psychology |

| Rhoads (1977) | Case studies | Employees across different occupations | — | Negative health consequences | Journal article | Health |

| Shields (1999) | National survey data/ archival | Canadian population | Canada | Negative health consequences | Journal article | Health |

| Cortes and Pan (2017) | Archival | Tertiary-educated individuals | USA and Western European countries | Negative macro-level consequences | Journal article | Economics |

| Cha (2010) | Archival | Dual-earner married couples | USA | Negative macro-level consequences | Journal article | Sociology |

| Cha and Weeden (2014) | Archival | Non-self-employed workers | USA | Negative macro-level consequences | Journal article | Sociology |

| Gicheva (2013) | Archival | GMAT registrants | USA | Positive consequences | Journal article | Economics |

| Kuroda and Yamamoto (2019) | Employer-employee matched panel survey | Firms with >100 employees | Japan | Positive consequences | Journal article | Psychology |

- Notes: GMAT, Graduate Management Admission Test; MBA, Master of Business Administration.

| Paper | Method | Setting | Location | Accounting area | Topic | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen et al. (2021) | Archival | Audit | USA | Audit | Audit workload | Journal article |

| Persellin et al. (2019) | Survey | Audit | USA | Audit | Audit workload | Journal article |

| Sweeney and Summers (2002) | Survey | Public accountants | USA | Audit | Audit workload | Journal article |

| Awasthi and Pratt (1990) | Experimental | Accounting task | USA | Managerial accounting | Effort duration | Journal article |

| Sprinkle (2000) | Experimental | Generic | USA | Managerial accounting | Effort duration | Journal article |

| Cloyd (1997) | Experimental | Tax | USA | Tax | Effort duration | Journal article |

| Chan et al. (2021) | Experimental | Generic | USA | Managerial accounting | Effort duration and effort intensity | Journal article |

| Yatsenko (2022) | Experimental | Generic | USA | Managerial accounting | Effort duration | Journal article |

| Panel A: Paper category organized by year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper category | Before 1993 | 1993–1997 | 1998–2002 | 2003–2007 | 2008–2012 | 2013–2017 | 2018–2023 | Total | Total (%) |

| Proposed reasons for overwork | 0 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 21 | 49 |

| Consequences of overwork | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 14 | 33 |

| Accounting articles | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 19 |

| Total | 2 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 43 | 100 |

| Panel B: Method organized by year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Before 1993 | 1993–1997 | 1998–2002 | 2003–2007 | 2008–2012 | 2013–2017 | 2018–2023 | Total | Total (%) |

| Theoretical model | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Experimental | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 17 |

| Archival | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 17 |

| Survey | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 24 |

| Analytical model and survey | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Interview | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Employer-employee matched panel survey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Othera | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 20 |

| Total | 2 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 11 | 41 | 100 |

- Notes: In Panel A, Kuroda and Yamamoto (2019) and Major et al. (2002) are repeated—they are in both the “Proposed reasons for overwork” category and the “Consequences of overwork” category. Thus, the total number of unique papers is 41, as indicated in Panel B.

- a Other includes synthesis, national survey data/archival, survey/archival, field study, theoretical model and historical trend analysis, meta-analysis, case studies, and qualitative analysis.

FINDINGS

In this section, I provide my findings from my review of the overwork literature. I first provide an overview of the construct of employee overwork, followed by a discussion of settings in which overwork pervades. I follow this with the literature that discusses potential reasons for employee overwork, and then the literature that discusses the consequences of overwork. Finally, I discuss findings on constructs related to overwork in the accounting literature. I provide my findings from my review of the literature in the conceptual model in Figure 1.

Overview of Employee Overwork

The phenomenon of employees' long working hours, which I label “overwork,” has been defined in several ways. It can be defined as working longer than 40 or 50 h a week, or more subjectively, as working beyond one's capacity (e.g., Cha, 2010; Cortes & Pan, 2017; Feldman, 2002; Golden, 2009). It can also be defined as employees working beyond contractual, statutory, or internal firm policy standard working time for no immediate additional monetary gain (Consultancy.eu, n.d.; Feldman, 2002; Ladva & Andrew, 2014; Mokhtar, 2023). Although the literature uses slightly differing definitions for the overwork construct, it generally captures the phenomenon of employees voluntarily working above and beyond a reasonable threshold of working time (Feldman, 2002). In my review, I do not distinguish between the exact definitions used in the different papers included, but rather I take a wider view in capturing the literature's discussion of employees working long hours.

I discuss the settings in which overwork is commonly found in the following section.

Settings with Overwork

Overwork is often found in the broad context of professional employees (e.g., Coffey, 1994; Golden, 2009; Kunda, 1995; Ladva & Andrew, 2014; Lewis, 2007; Mazmanian et al., 2013; Michel, 2011; Perlow, 1999; Perlow & Porter, 2009). This category of workers consists of employees who are well-educated and qualified, and who generally apply their knowledge to specific customer problems (Michel, 2011). Their work tends to involve “high levels of customer engagement, extensive customization, knowledge intensity, and low levels of capital intensity” (Brandon-Jones et al., 2016, p. 9). These employees work in a wide range of jobs, such as accounting, legal, architecture, engineering, technology, banking, consulting, and research and development (Brandon-Jones et al., 2016).

Proposed Reasons for Overwork

In this section, I outline findings related to proposed reasons for employee overwork. Extant research outside the accounting literature, in the fields of management, economics, and psychology, has pondered the important question of why employees overwork. For example, Feldman (2002) proposes a theoretical model that can help explain why managers work long hours. He proposes a four-pronged model consisting of economic factors, individual factors, job factors, and organizational factors.

Although there are various ways to categorize the factors that may explain why employees overwork, I have chosen to align my classification with Feldman (2002). This provides a way of organizing the papers that I found in my literature review in an organized fashion. Some factors (e.g., job factors and organizational factors) are particularly relevant from a management accounting perspective and can be considered at various stages in control system decisions.

Economic Factors

Feldman (2002) proposes three economic factors that firms may face and that in turn would lead employees in the firm to work longer hours. He proposes that firms that face competitive pressures from other firms, those that have a decline in corporate profits, and those that have threats of layoffs would be more likely to have managers that work longer hours. He proposes that under these organization-threatening conditions, managers may be more willing to work long hours to help ensure the success of the firm, or they may be pressured to do so by shareholders/stakeholders. Further, Golden (2009), a theoretical paper, also proposes several economic-level factors that may determine workers' desired hours: (1) employees' current real wage rates: employees can afford to work fewer hours if their wages are higher, although he argues that this is a basic economic premise that does not do a good job of explaining current long hours; (2) employees' anticipated rewards for working long hours: employees will work longer hours if they expect this to lead to better career progression; (3) the prestige that comes with working long hours: employees will work longer hours when this leads to higher status in the long term, by allowing them to consume status-conferring goods and services; and (4) employers' demand for long hours: employers dictate long work hours and workers may not have other options but to accept these hours.

Although economic factors are theorized to play an important role in predicting employees' long hours, studies stress that there are other critical determinants of overwork. I elaborate on these potential determinants in what follows.

Individual Factors

Feldman (2002) also proposes that individual-level factors play a role in predicting managers' working time. These factors include gender (he proposes that male managers are more likely to overwork), marital and family status (single managers and those without children are more likely to overwork), and the salience of the breadwinner role (the more salient this role the greater the overwork). Other factors are one's ability to adapt to behavior in a group (such that this positively predicts overwork), one's conscientiousness as a personality trait and one's achievement motivation (such that both positively predict overwork), and one's investment in outside-work activities (such that this negatively predicts overwork). Complementing Feldman's (2002) individual-level factors, Golden (2009) theorizes that longer hours can be predicted by employees’ intrinsic motivations or benefits acquired from work, such that employees will work longer if their work is more intrinsically rewarding.

Empirical evidence helps support that individual-level factors impact working hours. Ng and Feldman (2008) use a meta-analysis to support an identity framework that predicts that variables impacting an individual's occupational identity are predictors of the number of hours worked. These variables include individuals' current salary, career satisfaction, number of promotions, work centrality to the self, career interruptions, education level, work experience, and networking. This is because these variables are associated with individuals' career success, focus, and investment. They find that these variables are indeed the strongest predictors of hours worked. This is further supported by Frei and Grund (2020), who show that in a sample of doctoral students and doctoral degree holders, more career-oriented individuals, as opposed to those with more family responsibilities, work significantly more hours. Similarly, Major et al. (2002) survey employees at a Fortune 500 company and find that stronger career identities and fewer responsibilities away from work are associated with more time at work. Wallace (1997) finds, using survey evidence of lawyers, that a feeling that work is a central part of the individual's life is associated with longer work hours. Further, Brett and Stroh (2003) use survey evidence and find that male managers who worked the longest hours received extrinsic rewards for doing so and were the most psychologically involved in their work, even holding their extrinsic monetary compensation constant. Female managers, in contrast, seemed to have multiple reasons for working long hours, including making a trade-off between leisure time and earning money, and receiving extrinsic monetary rewards for the long hours they work. Kuroda and Yamamoto (2019) use panel survey data about Japanese workers and find that although longer work hours have a negative effect on workers' mental health, working longer than 55 h a week is associated with increasing job satisfaction (proxied by workers' satisfaction with job promotion). The study implies that workers may choose to work extreme hours because they overvalue the satisfaction they obtain from work and underestimate the negative effects on their mental health.

Job Factors

Feldman (2002) further proposes job-level factors that predict managers' work hours. These are particularly relevant to the management accounting literature. He proposes that when managers' work is less tangible, managers work longer hours to demonstrate their work. He also proposes that when managers' work is appraised less specifically and the appraisal criteria are less measurable, employees will be evaluated on their facetime and working hours. This is supported by Wick (2020), an accounting dissertation study that uses an experiment to support the proposal that when employees' output cannot be objectively assessed, employees' workday duration is used to evaluate the quality of their work when the purpose of their evaluation is a bonus reward (rather than a promotion). Feldman (2002) also proposes that when managers are evaluated on their performance on discretionary and interpersonal behaviors, rather than just their performance on their tasks, they are more likely to work longer hours because this helps them build relationships with their peers.

A 1998 report by the Institute for Employment Studies, an independent center for research in the United Kingdom, provides some empirical evidence that corresponds to Feldman's proposed job-level factors. The institute conducted a field study with 12 employers in the United Kingdom to understand the reasons behind the long hours employees worked (Kodz et al., 1998). Although this is not an academic study, it provides an idea of the reasons that employees feel they overwork, and it corresponds with much of the extant academic literature. They find that employees overwork due to their high workload and work pressures, tight deadlines, the pressure to perform well at work, and high customer expectations. Employees also feel that working long hours is necessary to be promoted in their jobs. More evidence is presented in Wallace (1997), mentioned previously, which finds that individuals feeling work overload, such that they feel that they do not have enough time to complete their work tasks, work longer hours.

Organizational Factors

Finally, Feldman (2002) proposes organizational factors as predictors of long working hours. These are also especially relevant to the management accounting literature. Feldman (2002) proposes that firm culture predicts long working hours. He also proposes that employees whose personalities fit the long hours culture select into firms with such cultures and are less likely to quit, while the opposite holds true for employees who do not fit these cultures. In this way, the long hours culture is perpetuated. Relatedly, Landers et al. (1996) present an analytical model and survey evidence that indicates that the income sharing in law partnerships incentivizes these law firms to create a work norm that requires their associates to work long hours because they are screening for associates with the propensity to work long hours who can contribute more to shared income when they are partners. Barlevy and Neal (2019) similarly argue, using an analytical model and survey evidence, that professional service firms require their associates to work long hours to facilitate finding new partners. Sousa-Poza and Ziegler (2003) develop an analytical model and use survey evidence that indicates that firms hire workers that work long hours in their attempt to sort high productivity from low productivity workers in an asymmetric information setting where worker productivity is unobservable. In this way, they also induce productive workers to work inefficiently long hours. Relatedly, Afota et al. (2019) develop a theoretical model to explain how employees are influenced by their supervisors to work longer hours through social contagion. They propose that employees will imitate their supervisors' long working hours when their supervisors' perceived status is higher, when work is more central to the employee, and when the subordinate identifies more strongly with their supervisor.

Additional empirical evidence sheds more light on this. For example, Brett and Stroh's (2003) survey evidence indicates that female managers exhibit evidence of social contagion in their work hours, such that managers who work extreme hours are more likely to be in the financial services industry. They reason that the financial services industry is one that is “the bellwether of overwork” (p. 68), such that social interaction within the industry perpetuates the overwork culture. Similarly, Maume and Bellas (2001) survey a sample of families in Ohio in 1998 and 1999 and find that the best determinant of individuals' working hours is how demanding their supervisors are. Another case in point is a study by Eastman (1998), which examines the extent to which individuals' chosen number of work hours depends on how long their colleagues work rather than on their own desired number of hours. He conducts a survey with MBA students and asks respondents how many hours they would work, with commensurate pay, if their colleagues worked different numbers of hours. He finds that respondents' chosen number of hours increases as the number of hours their colleagues worked increases, such that individuals' chosen number of hours is longer than they themselves desire.

Recent qualitative evidence also supports this. Lupu and Empson (2015), an interview study at an accounting firm in France, suggest that employees overwork because they are inadvertently taken in by the game of trying to enhance their status and obtain recognition in the field. Similarly, Peticca-Harris et al. (2015) study blogs by the spouses of game developers about the extreme working conditions in the industry. They suggest that video game developers work long hours due to a combination of a love for their work and “neo-normative control mechanisms” in the form of project-based work and the importance of meeting project deadlines.

On a parallel but slightly different note, Kang et al. (2017) propose that, in the context of Asian employees, Eastern culture, and specifically Confucian values, may lead to Asian employees' propensity to work overtime. Although this study does not directly examine an organizational factor, rather a cultural one, the Confucian element of Asian culture seemingly influences the culture of Asian organizations.

Taking a step back, within the extensive literature on why employees work long hours, the use of management controls in organizations and how they drive employees to overwork is seldom studied. Two of the few papers that consider how management controls within organizations can lead to overwork are Ladva and Andrew (2014), which is a qualitative study, and Mokhtar (2023), which is a managerial accounting dissertation. Ladva and Andrew (2014) propose that in the auditing context, a combination of formal and informal controls combine to create the overwork culture in accounting firms. These include auditors being pushed to work within budget, auditors' concern for looking efficient in their work, and auditors' career aspirations. Mokhtar (2023) proposes and finds experimental evidence that subjectivity in performance evaluation and group identity interact to determine employees' levels of overwork, such that higher subjectivity in performance evaluation and stronger group identity lead to higher levels of overwork. Despite this, we need a much more extensive examination of the management controls that lead to overwork and why they do so.

Tie-in with Management Accounting Research

Overall, then, we can consider the above factors in the context of management accounting research. Importantly, for overwork to become a construct that is more familiar in the management accounting literature, different controls within organizations should be studied as antecedents, or reasons, for overwork. Some of the current literature noted above can be directly built on within management accounting research, such as the job factors and organizational factors noted above. For example, within Feldman's (2002) job factors, he proposes that managers may overwork when they are evaluated on discretionary tasks rather than simply on their task performance. This can be directly related to management controls research that examines controls that are not directly related to task performance, such as those that encourage helping behavior among employees (Black, 2023). Further, the organizational factors noted above consist of informal controls; these are important from a management control perspective (e.g., Kachelmeier et al., 2016) and can inadvertently lead to overwork. I expand on future research opportunities within the management accounting literature in Section 4.

Consequences of Overwork

In this section, I discuss some of the negative and positive consequences of overwork that have been documented in the literature.

Negative Consequences

Negative consequences to overwork have been studied in the literature. Studies find that overwork can lead to a lack of efficiency and employee burnout, which have direct effects on employee turnover, absenteeism, and job performance (Babbar & Aspelin, 1998; Brett & Stroh, 2003; Burke, 2009; Carmichael, 2015; Golden, 2012; James, 2013; Kodz et al., 1998; Lupu & Ruiz-Castro, 2021; Steinmetz et al., 2014; Sweeney & Summers, 2002). Below I expand on different consequences to overwork categorized by domain, specifically, consequences to work, consequences outside of work, health consequences, and macro-level consequences.

Consequences to Work

Golden (2012), writing for the International Labour Organization, notes evidence that worker performance in a white-collar workforce decreases when they work 60 or more hours per week. He also notes that high overtime levels can impact employee morale, productivity and absenteeism, and that overworked employees are likely to make more mistakes at work. Conversely, he notes, shorter hours are associated with higher rates of output in many industries in the United States. This is consistent with Pencavel (2015), who examines a sample of munition workers during the First World War and finds that after a threshold of 48 h a week, there is a decline in the marginal product of hours. Further, “those weeks without a day of rest from work had about 10% lower output than weeks when there was no work on Sunday holding weekly hours constant” (p. 2072). Similarly, Steinmetz et al. (2014), using data from a web survey, find that working overtime is associated with a lower intention to stay among healthcare employees in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands.

Meanwhile, at the organizational level, Mazzetti et al. (2014, 2016) find that work environments that endorse overwork lead to workaholic employees, which is a “negative kind of involvement in one's job,” where employees work excessively and persistently think about their work, even when they are not working, and that this is especially true for employees that are “high in achievement motivation, perfectionism, conscientiousness, and self-efficacy” (p. 227).

Consequences Outside of Work

Overwork also has consequences for family life (Burke, 2009). For example, Shafer et al. (2018) use data on a sample of 590 IT workers in the United States and find that women partnered with men that work long hours, compared to women partnered with men who work a standard workweek, perceive higher stress levels and lower relationship quality. Similarly, Major et al. (2002) conduct a survey on employees in a Fortune 500 firm and find that working longer hours is associated with more work-family conflict and is indirectly associated with psychological distress in employees. The literature, in turn, indicates the impact of work-family conflict on employee job satisfaction (Lapierre et al., 2008), an important corporate social responsibility (CSR) consideration for firms and an indicator of future financial performance (Banker & Mashruwala, 2007; Dhaliwal et al., 2012). Thus, overwork consequences outside of work still have an impact on employee outcomes within a firm, indicating the pervasiveness of overwork consequences and the value of examining overwork in managerial accounting research.

Health Consequences

As early as 1977, Rhoads (1977) notes physical health consequences due to overwork in what he calls open-ended occupations, such as law and accounting professions. Some physical consequences include fatigue, difficulty concentrating, anxiety, insomnia, depression, and memory lapses. Shields (1999), examining overwork in Canada, used the Canadian National Population Health Survey between 1994 and 1997 and found that long hours increased negative health behaviors, including smoking, unhealthy weight gain, and drinking alcohol. While there are other studies that examine the health consequences of overwork (e.g., Wang et al., 2021), I do not include these studies in my literature review as they comprise a large literature that is not directly relevant to accounting research.

Macro-Level Consequences

On a macro level, Cortes and Pan (2017) use cross-country evidence to show that when more skilled men work longer than 50 h a week, the labor force participation rate of skilled, ever-married women goes down. They also find that when an occupation has more skilled men working longer than 50 h a week, this reduces the percentage of skilled, ever-married women in that occupation. In the same vein, Cha (2010) examines the impact of overwork on women; specifically, she uses archival panel data to examine the effect on wives' careers when their husbands work long hours and finds that husband overwork increases the likelihood that their wives will quit their jobs. The reverse effect does not seem to hold true, such that wives working long hours does not impact whether their husbands will quit. The effect of husbands working long hours on their wives quitting is even stronger when they have children, compared to if they are childless. She argues that long hours thus perpetuate arrangements in households where men are the breadwinners and women are the homemakers, when these households were once dual income.

Relatedly, Cha and Weeden (2014) use archival data to support that overwork contributes to the wage gap between men and women; this is because men are more likely to overwork than women, and because overwork comes with a wage premium. This wage premium does not refer to an immediate monetary gain received by employees for the time they work above contractual, statutory, or internal firm policy standard working time. Rather, it refers to a wage premium trend that occurs due to several possibilities, including overwork being concentrated “among highly educated, professional, and managerial workers” who experienced a large wage growth over the years (p. 460), as well as tournament-style compensation systems that may use overwork as a proxy for workers' productivity and cause overworkers to “win” the competition (p. 460), or even due to macrostructural changes that mean that core employees who tend to overwork are paid more than employees “who work part-time, under subcontracts, or in temporary positions for lower pay” (p. 461).

Positive Consequences

Despite the negative consequences associated with overwork, it is evident that firms value and reward it, as supported by Gicheva (2013), who finds a positive association between long hours and wage growth in data from a panel survey. Among other things, this is likely because firms see overworking employees as committed to their jobs (Brett & Stroh, 2003). Further, as noted earlier, Kuroda and Yamamoto (2019) find that Japanese workers who work more than 55 h a week have increasing job satisfaction with hours worked, at least as it relates to satisfaction related to job promotion. This suggests that at the individual level there may be positive consequences to overworking.

At a more fundamental level, firms benefit from overwork because it is cheaper to hire fewer employees who each overwork than to hire more employees to work the same number of hours (Dembe, 2009). More broadly, from a management accounting perspective, overwork may be considered an indicator of increased effort since it is a form of effort duration. This in turn may be seen by firms as an indication of better alignment between employee and firm objectives. However, importantly, overwork is at a specific end of the effort duration construct, such that it can lead to either better or worse firm performance.

Tie-in with Management Accounting Research

Examining the above research from a management accounting perspective reveals gaps and presents important opportunities for future research. For example, research is needed that examines how overwork affects the vital managerial control social effects of employee fairness perceptions, honesty, reciprocity, and trust in their firms and managers (Birnberg et al., 2006; Sprinkle & Williamson, 2006). Building on this, research should consider interventions against the harmful consequences of overwork, for example, if overwork is found to create negative employee fairness perceptions. Further, studies are needed to examine the variation between firms in the balance between negative and positive overwork consequences. For some firms, overwork may be a good representation of employee effort. However, for firms that find that the negative consequences of overwork outweigh any positive effects, they may consider alternating between management controls to configure the balance of overwork. For example, results controls may be emphasized in lieu of action controls, or personnel in lieu of cultural controls (Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017). It may be that personnel controls, such as hiring employees with a propensity to overwork, may cause the firm's culture to be more harmfully inclined to overwork. As another example, the balance of subjectivity versus objectivity in performance measurement systems may also create differences in the consequences of overwork in an organization. I expand on future research opportunities in overwork within a management accounting context in Section 4.

In what follows, I discuss findings from the accounting literature on constructs related to overwork to better bring the construct of overwork closer to an accounting audience.

Constructs Related to Overwork in the Accounting Literature

Overwork is important to examine in an accounting context, particularly from a management accounting perspective. Management accounting research is broadly interested in how managerial controls can be used to mitigate employee control problems, such as a lack of employee motivation (Sprinkle, 2003; Van der Stede, 2015). Interestingly, in settings where overwork occurs, employees are seemingly very motivated, working beyond their contractual, statutory, or internal firm policy standard working time for no immediate additional monetary gain; yet, we have little understanding of what management controls lead to this overwork and why employees do so. To bring the construct of overwork closer to an accounting audience, I discuss constructs related to overwork that have been examined in the broad accounting literature. Although the constructs studied in the audit and management accounting literatures are not necessarily the same constructs of overwork as defined in other literatures (especially the construct of effort duration), as noted below, I include them in this literature review primarily as a way of integrating the overwork literature from other disciplines with that of accounting.

First, the audit literature examines constructs related to overwork, such as workload pressure and audit busy season (e.g., Agoglia et al., 2010; López & Peters, 2012). The auditing context exhibits overwork due to the “the tension between limited audit resources and the need to complete a high number of audit engagements within a limited time window” (López & Peters, 2012, p. 139). Generally, the literature indicates that overwork has negative consequences on auditors and their work quality. For example, Christensen et al. (2021), using archival data, find that higher audit team workloads have a negative effect on audit quality, particularly for workloads above 60 h a week.

Studies also indicate the adverse effects of overwork on auditors and their perceptions of their work. Persellin et al. (2019) indicate, using survey evidence, that auditors perceive their high workloads to lead to worse audit quality and worse job satisfaction. Sweeney and Summers (2002) use a longitudinal survey and find that by the end of busy seasons, when auditors worked an average of 63 h a week, there was a direct relationship between auditors' workload and job burnout, exhibited by emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in their job approach. Interestingly, the relationship between workload and burnout did not hold for the pre–busy season, even though auditors worked an average of 49 h per week. They propose that this could be because public accountants develop higher resistance to workload pressure.

More broadly, overwork is a component of effort duration, and the management accounting literature has examined effort duration as a dependent variable. For example, Awasthi and Pratt (1990) experimentally show that participants who are offered monetary incentives, compared to those under fixed pay, spend more time on their tasks. Sprinkle (2000), in an experimental study examining employee learning and performance, finds a similar effect: participants receiving incentive-based contracts spend more time on the task than those receiving flat-wage contracts. In an experiment, Cloyd (1997) finds that accountability—being required to justify decisions to others—increases tax professionals' effort duration on a tax-research task. Chan et al. (2021) show that when employees are rewarded for the time they spend working, they increase their effort duration but decrease their effort intensity due to their fairness concerns about their incentive system. Interestingly, Yatsenko (2022) examines the impact on workers' productivity of peers' effort duration being observable; he finds that social comparison incentivizes workers to reduce their effort duration (in the absence of information about peers' relative output) because workers want to compare favorably against each other on their ability, and ability is inversely related to effort duration.

Note that although overwork is a component of effort duration, as noted above, overwork is at a specific end of the effort duration construct, such that it can lead to either better or worse firm performance. Thus, it needs to be better understood as a distinct construct.

FUTURE RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES WITHIN THE ACCOUNTING LITERATURE

My review of the literature indicates several gaps in the overwork literature that provide opportunities for future accounting research, particularly in the field of managerial accounting. As a first step, management accounting researchers should be more aware of overwork as an important construct to study, both as a consequence of different management controls and as a critical antecedent to management control dependent variables. This is especially true since overwork is directly relevant to practice, such that management accounting research that examines overwork creates “usable knowledge,” rather than “academically self-referential knowledge,” an important contribution, as emphasized by Van der Stede (2015, p. 173).

Overwork can clearly be situated within a management accounting framework. Research in management accounting primarily focuses on how managerial controls can motivate employees, operating under the assumption that employees tend to be effort-averse (Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017; Sprinkle, 2003; Van der Stede, 2015). Conversely, in environments where overwork is common, employees work extensive hours without immediate extra compensation, and they attribute their prolonged work hours to self-imposed pressures rather than to their firms pushing them to overwork (Blagoev et al., 2018; Empson, 2018; Kellogg, 2009; Ladva & Andrew, 2014; Lewis, 2003; Lupu & Empson, 2015; Michel, 2011). Thus, the management controls that lead to overwork seem to do so in indirect ways that are not readily apparent to employees. My review of the literature reveals that we need a much better understanding of what management controls lead to overwork and why they do so. This presents an important research gap for management accounting researchers, specifically, in examining management controls that may not be intended to directly increase employee overwork but may unintentionally do so. Importantly, there is a dearth of research that examines factors that directly cause overwork, as much of the existing research uses survey and archival methods to examine overwork, as noted in this literature review (Ng & Feldman, 2008). Thus, using experimental methods that can test causality would be pivotal in this research literature, as it would allow us a better understanding of exactly why employees overwork.

Further, research on the consequences of overwork also primarily relies on panel and archival data to find that overwork leads to consequences like employee burnout and reduced morale (Golden, 2012). However, it is also important to closely examine how overwork directly causes managerial accounting consequences. For example, it would be interesting to examine changes in employees' goal selection and goal commitment due to different expectations that arise when they overwork (Lane, 2021). Another important avenue to research is how overwork impacts employees' efforts over the long run. For example, overworking employees may gradually reduce their effort in subsequent work periods if they feel that they are not being directly rewarded or if there is no reciprocation from their firm for their overwork. Relatedly, it is beneficial to understand when employee overwork is likely to lead to better employee performance evaluation. Wick (2020) is a study that looks at this space and is important to build upon. Further, it would be informative to examine whether circumstances in which employees are evaluated better for overworking are in line with the firm's ultimate managerial control objective of forming and executing firm strategy (Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017). Although it may seem that overworking employees are an indication of well-motivated employees, overwork may also be indicative of a lack of employee direction, such that employees might overwork as a substitute for well-directed work.

Building on this, more nuances should be explored, examining the settings in which overwork may have more negative than positive firm consequences. This is likely to depend on different factors, including the type of employee work, how and how frequently employees are evaluated and receive signals about their overwork, and the importance of different management controls in the firm, such as the relative importance of cultural and results controls (Malmi & Brown, 2008; Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017). It is important to also understand how management controls interact to cause overwork and how overwork itself may interact with a firm's management controls to impact employee performance, as part of considering management controls as a package (Malmi & Brown, 2008).

Lastly, there is also little research directly examining firm perspectives on overwork and whether firms see overwork as enhancing firm value and achieving firm objectives, and importantly, whether firms believe managerial controls that indirectly cause overwork are achieving their intended objectives. Although there are analytical papers that theorize that professional service firms propagate overwork due to their ultimate goal of finding employees who can be firm partners (e.g., Landers et al., 1996), research that directly converses with firms on their views is warranted, especially in light of growing firm initiatives like work-life balance policies (Barlevy & Neal, 2019). Firm views on overwork may differ across industry and country. More than that, understanding firms' perspectives on overwork can help us better understand the reasons why overwork persists in firms despite noted negative employee consequences due to overwork. It would also help us understand the management controls that firms see as directly or indirectly causing overwork. Overall, management accounting researchers are well-placed to examine the important topic of overwork and how it aligns with firm objectives.

CONCLUSIONS AND LIMITATIONS

In this literature review, I examine the literature on employee overwork, discussing findings on both the antecedents and consequences of employee overwork. In order to provide a comprehensive overview of the overwork literature, which is predominantly sourced from outside the accounting literature, I perform a systematic review of the research. I discuss 21 papers related to proposed reasons for overwork and 14 papers related to the consequences of overwork. This research is predominantly in the organizational behavior, human resource management, economics, and psychology fields. It uses a variety of research methods, but mainly survey and archival methods. Different countries are represented in the research, although they are primarily Western industrialized countries. I also discuss 8 accounting papers discussing constructs related to overwork (namely audit workload and effort duration), predominantly in the audit and managerial accounting literatures.

In sum, I find several factors have been proposed to lead employees to overwork, namely economic, individual, job, and organizational factors (Feldman, 2002). Further, despite firms valuing overwork (Gicheva, 2013), the literature documents undesirable consequences to overwork, including negative consequences to work, negative consequences outside of work, negative health consequences, and important macro-level consequences. This paper also discusses gaps in the overwork literature and opportunities for future research in overwork from a management accounting perspective.

My review of the overwork literature makes important contributions to the accounting literature and to practice. First, as is often discussed in the popular press, the phenomenon of employees working long hours is commonplace, and it has become more prevalent since the COVID-19 pandemic (Beheshti, 2021; Hewlett & Luce, 2006; Karaian & Sorkin, 2021; Vershbow, 2021). Thus, overwork is an important phenomenon that managers should continue to examine in their firms and researchers should understand more fully. My review integrates current insights on overwork and provides a basis for researchers and managers to understand the environment and implications related to overwork.

Second, my synthesis of the existing research on overwork allows for gaps in the literature to be more apparent for future research, and I conduct my literature review with the aim of contributing to the management accounting literature, in particular. I find that, importantly, there is little empirical evidence that examines management controls that lead to overwork and that examine a direct causal relationship between management controls and overwork (Mokhtar, 2023). Similarly, an examination of the consequences of overwork as it relates to managerial accounting dependent variables is warranted. Thus, there are important research gaps in the management accounting literature that present opportunities for future research. This literature review also contributes to bringing overwork as a distinct construct to the management accounting literature.

Like all papers, this paper is subject to limitations. Despite my thorough search of the literature, including help from a research assistant, I might have missed papers on overwork, especially because I did not limit my search to specific journals but conducted a wider search of several subject literatures using various scholarly databases. Further, as with all literature reviews (Massaro et al., 2016), there was an element of subjectivity in choosing the papers included, at two different stages: first, at the stage where I chose papers that are related to the subject of overwork, as defined at the beginning of the paper, and second, at the stage where I chose papers related to either the “antecedents of overwork,” “consequences of overwork,” or “overwork in the accounting literature.” Despite these potential limitations, this paper can serve as an important starting point for accounting researchers in their examination of overwork.

REFERENCES

- 1 This is similar to prior accounting literature reviews conducted that use a systematic approach to reviewing the literature, such as Lane (2021), Borghei (2021), Stuart et al. (2022), and Adjei-Mensah et al. (2024).

- 2 I remove references to “karoshi,” “a potentially fatal syndrome resulting from long work hours” (Kanai, 2009, p. 209) in my search, as this refers to an extreme form of negative consequence to overwork that is not directly relevant from an accounting research perspective.

- 3 Although “work-life balance” captures a different construct than “overwork,” as defined previously, I include it in my search for completeness, as many articles discussing overwork tend to touch on work-life balance. However, none of the articles I include discuss work-life balance outside the context of overwork.