An International Comparison of the Academic Accounting Professoriate*

Accepted by Merridee Bujaki and Leslie Berger. We thank Carla Carnaghan, the editor (Merridee Bujaki), Leslie Berger (editor-in-chief), and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and feedback.

ABSTRACT

enAn international comparison of the accounting professoriate provides useful information to both key decision makers and individual faculty. We compare characteristics of the academic accounting professoriate in the United States and Canada. Our comparison includes the size of accounting departments (measured by the average number of accounting faculty) and the relative level of research versus teaching focus in accounting departments (proxied by the proportion of tenure-track vs. non-tenure-track faculty). We also examine the relative mobility of accounting faculty (proxied by the number of faculty employed in the same country where they received their final degree vs. the number of faculty employed in a different country). We examine the time it takes for tenure-track faculty to obtain tenure and the time for tenured associates to become full professors, broken out by obtaining their final degree in the same country where they are employed versus faculty who obtained their final degree in a different country.

RÉSUMÉ

frComparaison à l’échelle internationale des corps professoraux en comptabilité

Une comparaison à l’échelle internationale des corps professoraux en comptabilité fournit de l’information utile aux principaux décideurs et aux professeurs à titre individuel. Nous comparons les caractéristiques de corps professoraux en comptabilité aux États-Unis et au Canada. Nous nous penchons notamment sur la taille des facultés de comptabilité (mesurée en fonction du nombre moyen de professeurs de comptabilité qu’on y retrouve) et le niveau relatif de recherche par rapport aux activités d’enseignement dans ces facultés (déterminé selon la proportion de membres du corps professoral occupant un poste menant à la permanence comparativement aux autres membres). Nous examinons aussi la mobilité relative des professeurs (déterminée par le nombre de professeurs qui travaillent dans le pays où ils ont reçu leur plus récent diplôme par rapport aux professeurs qui travaillent dans un autre pays). Nous évaluons le temps qu’il faut aux professeurs occupant un poste menant à la permanence pour obtenir leur permanence, et aux professeurs agrégés permanents pour obtenir leur titularisation, en ventilant les résultats selon qu’ils ont obtenu leur plus récent diplôme dans le pays où ils travaillent ou dans un autre pays.

University faculty in accounting have a significant mandate to educate a growing body of accounting professionals, many of whom become Certified Public Accountants in the United States or Chartered Professional Accountants in Canada. In the United States, the Pathways Commission report from July 2012 states, “Accounting information is central to the functioning of international capital markets and to managing small business, conducting effective government, understanding business processes, and raising and addressing questions about how economic decisions are made. . . . Persons educated and trained in accounting skills are, therefore, essential to the flow of financial information supporting economic activity” (Pathways Commission 2012). This underscores the importance of having a sufficient number of trained accountants. However, to date there have been few data available to systematically examine the structure of organizations that provide training to accountants, primarily the accounting departments at various universities in the United States and Canada. We note that there are many universities with accounting programs around the world (e.g., the London Business School in England and KAIST in South Korea); however, given the predominant focus of the Hasselback accounting faculty directories (which we use) on schools in the United States and Canada, we focus our analysis on these two nations.

An international comparison can inform key decision makers, such as business school deans, who would like to compare accounting department structures in the United States and Canada. This includes the number of faculty in individual departments and the research focus of various schools (proxied by the proportion of tenured/tenure-track faculty vs. the proportion of non-tenure-track faculty). Individual faculty (or even potential faculty, if someone is considering entering the academic profession) want to know about the opportunities for international relocation within the profession. For example, one might ask: if I get a PhD in the United States, what are my chances of moving to a faculty position in Canada? And if I work in a different country than where I got my PhD, will it take a longer or shorter time to obtain tenure?

The accounting professoriate has developed differently in various countries because it is subject to different governments and cultural factors. For example, the United States generally has more private money available to universities, but Canadian universities rely mostly on government funding.1 While we do not speculate on details of these factors (but note in our conclusion that this is a potential area for further research), we compare and contrast various characteristics of the professoriate in Canada and the United States. We use data from the Hasselback Directories of Accounting Faculty, produced from 1974 to 2016, to describe and contrast various characteristics of the professoriate.

The number of accounting schools provides some indication of the demand for accounting training, and accounting department sizes also vary. We count the number of schools included in Hasselback, and we proxy for accounting department size by using the number of individuals employed in each department for schools broken out by nation.

The relative proportion of tenure-track faculty versus non-tenure-track faculty is important for both individuals and institutions. Being tenure-track/tenured means that the individual can achieve, or has achieved, the right to permanent employment at their institution, subject to the survival of the institution and adequate fulfillment of the individual's responsibilities. Thus, tenure provides a significant amount of job security. Many institutions must maintain a certain proportion of tenured faculty to maintain external accreditation from organizations such as the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). Tenure-track faculty typically have PhDs or some other terminal degrees, such as a DBA (doctorate of business administration). Tenure-track faculty are expected to produce research and generally have a reduced teaching load, while non-tenure-track faculty have a stronger teaching focus and are less likely to be the “thought leaders” at their institutions.2 We examine the proportion of faculty classified as tenure-track versus non-tenure-track and compare US and Canadian schools.

There are factors suggesting an increase in international mobility between accounting faculty, but other factors suggest a decrease in international mobility. IFRS are accounting standards that are international in nature, allowing for accounting rules to be more consistent between countries and also allowing for greater mobility for faculty to move from one nation to another. But even with the growing acceptance of IFRS, many nations still have national standard-setting bodies (most notably, the FASB in the United States) that produce standards specific to a particular nation. Even nations following IFRS will often have their own idiosyncratic versions of IFRS and their own specific tax rules that many accountants in that nation must be familiar with (e.g., India recently adopted IFRS with seven “carve-outs” or nationally specific adjustments to IFRS; see IFRS 2018). This means that academic accounting faculty often need to have country-specific experience and training to educate accounting students for jobs within that country.

We count the number of faculty by their country of education and their country of employment. Most faculty are employed in the same nation where they obtained their PhD (although this does not preclude someone traveling from their country of birth to a different nation for their PhD and then staying in that nation for their employment), and we show the number of faculty educated in the same nation as their PhD versus the number of faculty who switched nations after their PhD (e.g., someone obtaining a PhD in the United States but moving to Canada to teach at a Canadian school). We expect that most faculty employed in a particular nation are also educated in that same nation but that growing multinational forces will result in faculty becoming more internationally mobile, and therefore in more recent years a greater proportion of faculty will be employed within a nation other than the nation where they obtained their final degree.

Finally, individuals may wonder about how long it may take them to obtain tenure if they are employed in the United States or Canada. They may also wonder how long tenure will take if they work in a different country from the one where they got their PhD. Similarly, they may wonder about how long it could take to become a full professor.

The United States remains a dominant force in accounting education throughout the world; we note a bias in our data because Hasselback directories are US publications, and earlier editions of Hasselback directories are more US-centric than later editions. However, Hasselback directories have come to include Canadian schools and many more faculty over time, and we believe that the data those directories provide have become more complete over time.3

BACKGROUND AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Bedard and Dodds (1994), in a dated but thorough paper, describe the characteristics of faculty at eight prominent Canadian schools.4 They report the number of faculty and the proportion of faculty with PhDs; the number of PhD graduates; faculty ranks; work experience; teaching load; allocation of faculty time to research, teaching, and service; and faculty salaries, among other items. While Bedard and Dodds report additional data from surveys sent to each school, we rely exclusively on data from Hasselback directories and are able to make comparisons between Canada and the United States. Carnaghan et al. (1994) describe publications in Contemporary Accounting Research, the flagship research journal of the Canadian Academic Accounting Association, from 1984 (its year of origin) to 1994. From 1992 to 1994, the editorial tenure of Michael Gibbins (a professor at the University of Alberta), 37% of papers accepted for publication in Contemporary Accounting Research had one or more authors from Canadian institutions, but Carnaghan et al. did not have data on where those individuals obtained their PhDs.

Bujaki and McConomy (2017) assess the productivity of Canadian academic accountants from 2001 to 2013 and show the proportion of publications in their list of top 10 accounting journals that are authored by Canadians.5 Our paper complements theirs by examining data on counts of faculty at Canadian and US schools broken out by where the faculty member obtained their PhD. Another relevant paper similar to Bujaki and McConomy (2017) is Richardson and Williams (1990), which does the same investigation but reports data from 1976 to 1989.

Bundy et al. (2019) examine the relationship between graduating school rank and the rank of the school hiring graduating accounting PhD students and report a positive correlation between the rank of the graduating school and the rank of the hiring school; that is, new PhD graduates tend to find jobs at schools of similar status. However, we are not aware of research comparing the nation of the graduating school with the nation of the hiring school.

Key decision makers, such as department heads, university administrators, and business school deans, can be informed by the data we provide. The number of universities offering accounting education is a measure of the demand for accountants in a given country. The value that a country places on accounting professionals and the degree of centralization in a given country will influence the size of the accounting department.6 Accordingly, our first two research questions are as follows:

Research question 1 (RQ1). How many schools offer accounting education in the United States and Canada?

Research question 2 (RQ2). What is the average faculty size of each accounting program?

Another area of interest deals with the research focus of schools in a given country. Tenure-track (and tenured) faculty are more expensive: the average 2016 salary for assistant accounting professors is $149,400, compared with an instructor (nontenured) salary of $82,500.7 Because they have a lower teaching load, more tenure-track faculty are needed to educate the same number of students. Non-tenure-track faculty typically teach six or more classes per year (vs. four or fewer for tenure-track and tenured faculty) and have annual salaries that are lower.8 In return for a lower teaching load, tenure-track faculty are expected to produce a more significant volume of research, typically measured by the number of publications in academic journals.9 Given the relative cost of tenure-track faculty, their proportion can serve as a proxy for the research focus of that school, where a higher proportion of tenure-track faculty suggests a greater value placed on research at that school, and a higher proportion of non-tenure-track faculty suggests a greater value on teaching at that school. The relative proportion of tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty for each country suggests the relative value the country places on research versus teaching. This leads to our third research question:

Research question 3 (RQ3). What is the average proportion of tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty in the United States versus Canada?

Individual faculty, and those considering becoming faculty by entering a PhD program, may wonder about their mobility. Accordingly, we count the number of faculty in the United States and Canada who got their PhD from the same country where they are employed. Stated as a research question, this is as follows:

Research question 4 (RQ4). What proportion of faculty in the United States and Canada obtained their final degree from that same country, and what proportion obtained their final degree from another country?

A related concern to potential faculty is how long it takes to obtain tenure if they obtain their PhD in a different country, and how long it takes to move from tenured associate to full professor. Faculty moving to a different country from their PhD school may face difficulty because they are in an environment with legal structures (e.g., tax rules and financial accounting rules) that they might not be familiar with. On the other hand, an education in a different country might inspire interesting research questions relative to domestic education. Stated formally, these are as follows:

Research question 5 (RQ5). How many years does it take, on average, for a person to obtain tenure in a given country?

Research question 6 (RQ6). How many years does it take, on average, for a person to obtain tenure if she obtains her PhD in the same country where she is employed, versus obtaining her PhD from a different country?

Research question 7 (RQ7). How many years does it take for a person to become a full professor?

METHODOLOGY

We draw our data from Hasselback directories of accounting faculty from 1980 to 2016. These directories are public information (available at http://www.jrhasselback.com/FacDir.html). We enter the data in machine-readable format and check the data for consistency and errors.10 We obtain information on faculty name, rank (assistant, associate, full professor, lecturer, visitor, etc.), school of employment and its country, and the school where the individual obtained their latest degree (and country). We also count the number of schools in a given country.

In some cases, Hasselback reports an individual's rank as “dean” or “director.” This does not reflect their academic rank but rather their position within the university; for example, a dean typically holds the rank of full professor but can sometimes be an associate or even assistant professor. In these cases, we search prior years where the individual's academic rank is reported and assume they maintained that rank after becoming dean or director. We search back as far as 16 years, and at that point if we cannot determine the individual's actual rank, we delete that observation.

We break our data into two national categories: Canada and the United States. A further examination of schools in Mexico and outside North America is also possible but would require reliance on only the most recent Hasselback directories. Hasselback produces directories reflecting academic school years (i.e., from the fall of one calendar year to the summer of the following year), and for brevity we use the first year to designate a particular directory, so our reference to the 1980 year reflects data in the 1980–1981 Hasselback directory. No directories were produced for the 2004, 2006, 2008, and 2010 years.11

RESULTS

Table 1 addresses RQ1 and RQ2. This table shows our counts of schools (panel A), individual faculty (panel B), and the average number of faculty per school (panel C) for the United States, Canada, and other nations. Raw numbers of schools have little usefulness for comparisons on a national level because national populations vary considerably (the United States has about 10 times the population of Canada). To make our comparisons meaningful, we obtain national population data from the Worldometer website (www.worldometers.info). To show time trends, we break our analysis further into five-year increments from 1980 to 2016. Because directories do not exist for some years in the 2000s (in particular, for 2010), our year categories disclosed in more recent years are 2005 and 2011, then 2016.12

| Panel A: Schools | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Canada | ||||||

| Number of schools | Population | Schools per million people | Number of schools | Population | Schools per million people | Total schools | |

| 1980 | 365 | 229,476,354 | 1.59 | 15 | 24,416,886 | 0.61 | 380 |

| 1985 | 477 | 240,499,825 | 1.98 | 20 | 25,744,810 | 0.78 | 497 |

| 1990 | 609 | 252,120,309 | 2.42 | 30 | 27,541,319 | 1.09 | 639 |

| 1995 | 786 | 265,163,745 | 2.96 | 38 | 29,164,152 | 1.30 | 824 |

| 2000 | 821 | 281,710,909 | 2.91 | 40 | 30,588,383 | 1.31 | 861 |

| 2005 | 832 | 294,993,511 | 2.82 | 40 | 32,164,309 | 1.24 | 872 |

| 2011 | 871 | 311,885,282 | 2.79 | 39 | 34,557,335 | 1.13 | 910 |

| 2016 | 889 | 323,015,995 | 2.75 | 40 | 36,382,944 | 1.10 | 929 |

| Panel B: Individual faculty | Panel C: Average faculty per school | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Canada | Total | United States | Canada | Overall | |

| 1980 | 3,156 | 119 | 3,275 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 8.6 |

| 1985 | 4,355 | 183 | 4,538 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 9.1 |

| 1990 | 5,471 | 292 | 5,763 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 9.0 |

| 1995 | 5,838 | 371 | 6,209 | 7.4 | 9.8 | 7.5 |

| 2000 | 5,933 | 357 | 6,290 | 7.2 | 8.9 | 7.3 |

| 2005 | 6,005 | 433 | 6,438 | 7.2 | 10.8 | 7.4 |

| 2011 | 6,618 | 454 | 7,072 | 7.6 | 11.6 | 7.8 |

| 2016 | 7,040 | 475 | 7,515 | 7.9 | 11.9 | 8.1 |

- Notes: The table shows counts of schools with accounting professors in the United States and Canada (panel A, scaled by national population), counts of the number of individual accounting faculty (panel B), and the average number of accounting faculty per school (panel C). Faculty include tenured and non-tenured faculty. Data are taken from Hasselback directories of accounting faculty for the years 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2011, and 2016.

Hasselback coverage has increased significantly over the years, and we are unable to fully distinguish between schools that existed in earlier years (e.g., Utah Technical College existed in 1982 but was not included in Hasselback until 1996, when the school carried the name Utah Valley State College, and in 2008 the school was renamed again to Utah Valley University) and schools that originated between 1980 and 2016 (e.g., California State University, Monterey Bay, originated in 1994). Canadian schools reported in Hasselback increased from 15 schools in 1980 to 40 by 2016. US schools reported in Hasselback increased from 365 in 1980 to 889 by 2016. We calculate the average schools per million people; in the United States, this average increased from 1.59 in 1980 to 2.96 in 1995, and decreased to 2.75 by 2016. The Canadian average per million shows a similar pattern, with 0.61 schools per million in 1980, increasing to 1.31 schools per million by 2000, and tapering to 1.1 schools per million by 2016.

Faculty counts increased in a similar manner to school counts. The average number of faculty per school (panel C) suggests that the average number of faculty at US schools decreased from 8.6 in 1980 to 7.9 in 2016, but increased for Canadian schools from 7.9 in 1980 to 11.9 in 2016. This suggests that accounting departments at Canadian schools grew while accounting departments at US schools shrank slightly.13 The overall average faculty at all schools reported in Hasselback stayed about the same, at around 8.1 faculty per school.

RQ3 addresses the number of tenure-track faculty versus non-tenure-track faculty as a proxy for the relative focus of teaching versus research. Tenure-track faculty are more likely to hold terminal degrees—usually a PhD but sometimes a DBA—and are more likely to be the “thought leaders” at a school. To obtain tenure, typically when the individual is promoted from assistant professor rank to associate, faculty must obtain a sufficient number of research publications. Standards for publications that count toward tenure vary considerably by school, with some schools requiring only a few publications in peer-reviewed journals, while others require as many as five or six publications at a handful of “top” journals. Non-tenure-track faculty typically have higher teaching loads and focus on teaching classes, while tenure-track faculty have a lower teaching load and are expected to produce more research. We assume that schools with more tenure-track (and tenured) faculty are likely to be more heavily involved in research and are more likely to be leaders in innovation in accounting, as compared with schools with a lower proportion of tenure-track faculty, which are more heavily focused on teaching.

Panel A in Table 2 shows the raw counts of faculty in tenure-track and non-tenure-track positions. Panel B shows the relative proportion of faculty and suggests that Canada and the United States show similar proportions of tenure-track versus non-tenure-track faculty, with the United States showing slightly more proportionate tenure-track faculty for years 1980, 1990, and 2005 and Canada showing proportionately more tenure-track faculty in other years.

| Panel A: Individual tenure-track faculty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Canada | Total | ||||

| Tenure-track | Non-tenure-track | Tenure-track | Non-tenure-track | Tenure-track | Non-tenure-track | |

| 1980 | 2,465 | 691 | 91 | 28 | 2,556 | 719 |

| 1985 | 3,461 | 894 | 148 | 35 | 3,609 | 929 |

| 1990 | 4,525 | 946 | 231 | 61 | 4,756 | 1,007 |

| 1995 | 5,029 | 809 | 330 | 41 | 5,359 | 850 |

| 2000 | 5,093 | 840 | 309 | 48 | 5,402 | 888 |

| 2005 | 5,090 | 915 | 364 | 69 | 5,454 | 984 |

| 2011 | 5,334 | 1,284 | 380 | 74 | 5,714 | 1,358 |

| 2016 | 5,505 | 1,535 | 399 | 76 | 5,904 | 1,611 |

| Panel B: Proportion of tenure and non-tenure-track faculty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Canada | Overall | ||||

| Tenure-track (%) | Non-tenure-track (%) | Tenure-track (%) | Non-tenure-track (%) | Tenure-track (%) | Non-tenure-track (%) | |

| 1980 | 78.1 | 21.9 | 76.5 | 23.5 | 78.0 | 22.0 |

| 1985 | 79.5 | 20.5 | 80.9 | 19.1 | 79.5 | 20.5 |

| 1990 | 82.7 | 17.3 | 79.1 | 20.9 | 82.5 | 17.5 |

| 1995 | 86.1 | 13.9 | 88.9 | 11.1 | 86.3 | 13.7 |

| 2000 | 85.8 | 14.2 | 86.6 | 13.4 | 85.9 | 14.1 |

| 2005 | 84.8 | 15.2 | 84.1 | 15.9 | 84.7 | 15.3 |

| 2011 | 80.6 | 19.4 | 83.7 | 16.3 | 80.8 | 19.2 |

| 2016 | 78.2 | 21.8 | 84.0 | 16.0 | 78.6 | 21.4 |

- Notes: The table shows counts of tenure-track and non-tenure-track accounting faculty (panel A) and the proportion of tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty to total accounting faculty (panel B). Tenure-track is defined as assistant, associate, or full professor rank, and all other ranks are designated as non-tenure-track (e.g., visiting professor, lecturer). Data are taken from Hasselback directories of accounting faculty for the years 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2011, and 2016.

The United States dominates along many dimensions because of its sheer size: there are simply more people in the United States than in Canada. In prior years, many nations followed US accounting standards, but this was problematic because US accounting standards, produced by FASB, reflect US needs and economic conditions that may be different in other parts of the world. The growth of IFRS reflects a counterbalancing force to US accounting standards, and the IASB makes an explicit effort to ensure geographic diversity; its 13 board members are drawn from the Asia/Oceanic region (3), Europe (3), the Americas (4), and Africa (1), with 2 at-large members (the chair and vice-chair).14 The chair and vice-chair do not reflect any particular region (but as of 2021 are from Europe and New Zealand).15 Using similar logic as the IASB, we assume that accounting education is best fulfilled by faculty reflecting international diversity and that dominance by one particular region is undesirable; for example, if the United States dominates accounting education in Canada, then the emerging cohort of Canadian professional accountants will be more familiar with US standards and business practices that may be different from Canadian practices.

This logic motivates RQ4 (what proportion of faculty in a given country obtained their final degree from that country?), and we break out faculty based on the country of their current school of employment, and then faculty based on the country in which they obtained their most recent degree. We are unable to determine the nation of citizenship (or residency) for faculty in Hasselback and note that faculty may obtain their final degree from a different country than their country of original residence.16

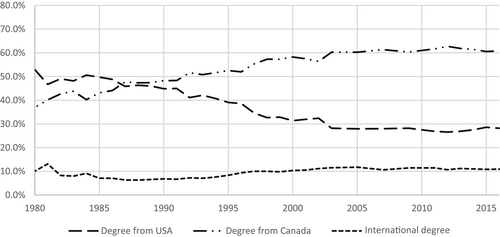

Because of the volume of data from 1980 to 2016, we show our results in Figure 1.

Notes: The figure shows the proportion of faculty employed in Canada and how this proportion has shifted over time. The long-dashed line shows the proportion of faculty with degrees from a US school, the double-dashed line shows the proportion of faculty with degrees from a Canadian school, and the short-dashed line shows the proportion of faculty with international degrees (i.e., degrees from a country outside of the United States or Canada).

Our nontabulated analysis for US schools reflects some extreme proportions: 98.5% of faculty in the United States in 1980 were also educated in the United States, and this decreased to 97.2% by 2016 (i.e., very little change). US faculty who obtained their degrees in Canada increased from 0.5% to 1% over that same period. These changes reflect a slight trend toward more multinational faculty in the United States, counterbalanced by the sheer size of the United States in terms of production of PhDs.17

Figure 1 shows the proportion of faculty at Canadian schools. US-trained faculty shifted from the greatest proportion at just over 50% in 1980 to 28% in 2016, and Canadian-trained faculty moved from 36% in 1980 to 61% by 2016. The growth of Canadian-trained faculty in Canada reflects the transition of the accounting professoriate in Canada from being US-dominated to having greater Canadian dominance. The relative proportion of internationally trained (i.e., outside the United States and Canada) faculty in Canada fluctuated by a small amount, moving from 10% in 1980 to 11% in 2016.

Results from Figure 1 are consistent with the observation of Zeff (2019) that the professoriate in Canada and the United States is closely intertwined, but we also note that our data suggest the interconnectedness has decreased over time in Canada. The slight increase in faculty in the United States coming from Canada and internationally suggests that the level of interconnectedness slightly increased in the United States.18

Accounting faculty who are familiar with accounting, auditing, and tax in a particular nation are better able to research those topics; for example, a US-educated professor would likely be better able to conduct research on US taxes and US GAAP, whereas a Canadian-educated professor would be a superior researcher in IFRS and Canadian tax. But faculty with a different perspective may be in a better position to ask and answer interesting research questions (“out-of-the-box thinking”). We next address RQ5 and RQ6 (how long does it take to obtain tenure in a given country, and how long will it take if you get a PhD from a different country?). Table 3 provides data to answer these questions.

| Panel A: Average years to promotion to associate by nation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Years to associate | p-value vs. United States | |

| United States | 5,136 | 6.54 | |

| Canada | 255 | 6.07 | 0.043 |

| Total/average | 5,391 | 6.52 | |

| Panel B: Average years to promotion to associate for faculty employed in the United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Years to associate | p-value vs. educated in United States | |

| Faculty educated in United States, employed in United States | 5,037 | 6.55 | |

| Faculty educated in Canada, employed in United States | 23 | 7.70 | 0.132 |

| Total/average | 5,060 | 6.56 | |

| Panel C: Average years to promotion to associate for faculty employed in Canada | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Years to associate | p-value vs. educated in Canada | |

| Faculty educated in Canada, employed in Canada | 121 | 6.12 | |

| Faculty educated in United States, employed in Canada | 105 | 6.50 | 0.461 |

| Total/average | 226 | 6.29 | |

- Notes: The table shows the total promotions from assistant to associate rank from 1975 to 2016 for faculty broken out by nation of employment and nation of education. Panel A shows a comparison of average years to promotion broken out by nation (United States and Canada). Panel B breaks out faculty employed in the United States based on the nation where they received their final degree, and panel C shows a similar breakout for faculty in Canada. p-values reflect comparisons between country of employment as Canada versus the United States (panel A) and comparisons with years to associate for home-educated faculty versus faculty educated outside their the employment country (panels B and C).

In panel A of Table 3, we count the number of accounting faculty who are promoted from assistant to associate professor rank (and we assume, following the practices of most schools, that these individuals obtained tenure), broken into national categories. Our overall time to tenure is 6.52 years; time to tenure is lower for Canada, at just over 6 years, and higher for the United States, at 6.54 years. Our p-values of significance reflect a comparison with the US time to tenure; Canada's time is significantly lower (p = 0.04). Panels B and C break out our analysis separately for schools in the United States and Canada; in panel B, we track the time to promotion for faculty educated and employed in the United States (5,037 faculty, 6.55 years), compared with Canada-educated faculty in the United States (23, 7.7 years).19 The difference between times for US- and Canada-educated faculty for faculty employed in the United States is not significantly different (p = 0.13).

Many individuals never become full professors in accounting and, accordingly, our promotion-to-full numbers are lower than our promotion-to-tenure numbers. The number of individuals who reach full professor rank is 3,155 (where we can identify both the country where they are employed and the country where they obtained their final degree). Because there is no looming “tenure clock” for these individuals, we are not surprised to see that, on average, it takes longer to move from associate-professor rank to full-professor rank. Table 4 shows our analysis to address RQ7 (how long does it take to become a full professor?), broken out by country and broken out by country of education.

| Panel A: Average years to promotion to full professor by nation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Years to associate | p-value vs. United States | |

| United States | 3,009 | 7.26 | |

| Canada | 146 | 8.27 | 0.022 |

| Total | 3,155 | 7.30 | |

| Panel B: Average years to promotion to full professor for faculty employed in the United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Years to associate | p-value vs. educated in United States | |

| Faculty educated in United States, employed in United States | 2,949 | 7.24 | |

| Faculty educated in Canada, employed in United States | 10 | 11.00 | 0.125 |

| Total | 2,959 | 7.25 | |

| Panel C: Average years to promotion to full professor for faculty employed in Canada | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Years to associate | p-value vs. educated in Canada | |

| Faculty educated in Canada, employed in Canada | 60 | 7.93 | |

| Faculty educated in United States, employed in Canada | 70 | 8.49 | 0.553 |

| Total | 130 | 8.23 | |

Panel A shows our breakout by individual country. US faculty who move from associate professor to full professor take an average of 7.26 years, and Canadian faculty who become full professors take significantly longer, at 8.27 years (p = 0.02).

However, there are no significant differences in the time needed to become full professor when the data are broken out by country of education versus country of employment, in panels B and C. For example, faculty educated in the United States and employed in the United States take 7.24 years to become full professor, and faculty educated in Canada but employed in the United States take 11 years (panel B). Because there are only 10 people in the US/Canada category, this difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.125). Faculty educated in Canada and employed in Canada need 7.93 years, and faculty educated in the United States but employed in Canada need 8.49 years; these numbers are not statistically different, either (panel C). It appears that the country of education makes little difference in terms of time needed to go from associate professor to full professor.

CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we use data from Hasselback directories to make a number of cross-country comparisons between Canada and the United States. We examine the number of schools and individual faculty, the ratio of tenure and non-tenure-track faculty, and the proportion of faculty employed in a given nation versus faculty educated in a given nation. We also compare the years needed to be promoted from assistant professor to associate professor (i.e., to obtain tenure) and the time needed to be promoted from associate professor to full professor by nation of education versus nation of employment. When comparing the number of schools per population, the United States has more schools per million people than Canada. Canadian schools have also become larger in terms of the number of faculty employed, while US schools have become slightly smaller. In more recent years, Canadian schools show a slightly higher proportion of tenure-track faculty versus US schools.

In general, faculty tend to remain in the same country where they obtained their degree; however, mobility is generally higher for Canadian-educated faculty versus US-educated faculty. In contrast, Canadian schools have trended toward having proportionately more Canada-educated faculty.

We caution against drawing strong conclusions from these results because there are many factors that we cannot control for; likely, the most significant factor is tenure requirements at individual schools. Faculty obtaining tenure sooner, for example, may do so because they have accepted positions at schools with more relaxed tenure requirements where tenure is more easily obtained; those accepting positions at more demanding schools may take longer because they could fail to obtain tenure at their first school, then move to another school and require more years before “going up.” Fewer years to obtain tenure does not necessarily suggest better training, higher intelligence, or superior work ethic.

In spite of these issues and caveats, our paper provides insights into differences between countries in terms of accounting faculty size and international mobility, and as such complements prior work such as Oler et al. (2021a, 2021b), who examine faculty promotion and mobility but do not break their data into country of education versus country of employment. As more data on accounting faculty on an international level become available, we provide a starting point for several avenues of continued investigation. Future work using more recent Hasselback directories (or alternative sources of information) could make comparisons between schools outside of the United States and Canada. Future work could also examine possible reasons for differences between Canadian and US accounting departments, and the reasons for different career choices (e.g., factors explaining why some professors reach full professor status and others remain as tenured associates). Changes in requirements for professional accountants may also have an impact on academic pursuits (e.g., the effect in the United States of the “150-hour rule,” or the effect in Canada of the merging of CA, CMA, and CGA designations in 2014).