Explaining Investors' Fixation on Increasing Revenue: An Experimental Investigation of the Differential Reaction to Revenues versus Expenses*

Accepted by Adam Presslee and Leslie Berger. The authors thank participants from the 2019 ABO Conference, the 2019 BYU Accounting Conference, and the Craft of Accounting Research workshop at the 2017 CAAA Conference for their insightful comments. The authors also thank Adam Presslee (associate editor) and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. Funding for this paper was provided by the Chartered Professional Accountant Education Foundation, the Dhillon School of Business, and the Lazaridis School of Business and Economics.

ABSTRACT

enPrior research has demonstrated that investors have differential reactions to revenue increases versus expense decreases in firms with positive earnings surprises. We use the experimental method to explain how this differential reaction is, at least in part, due to a heuristic-like process in investors' decision-making processes. Critical to our study, we further demonstrate that when revenue increases explain even a small portion of that surprise, investors make more positive judgments about the firm than one might expect. This somewhat surprising result occurs even though those same investors provide similar earnings forecasts for the next period, indicating that our results are not entirely caused by differential judgments regarding the persistence of the earnings surprise. These findings are consistent with the halo effect, a phenomenon described in psychology literature in which, when making evaluations, one's focus on a certain salient factor impacts assessments regarding other factors. This article helps to explain some of the complexities with individual investor behavior when evaluating the impact of changes in revenues and expenses. Specifically, investors' preference for revenue increases as compared to expense decreases is partially caused by biases that are not obvious to investors, making it difficult for them to adjust for these biases.

RÉSUMÉ

frExpliquer la fixation des investisseurs sur l’augmentation des revenus : enquête expérimentale sur la différence de réaction face aux revenus et aux dépenses

La recherche antérieure a démontré que les investisseurs ont des réactions différentes face aux augmentations des revenus par rapport aux réductions des dépenses dans le cadre de surprises positives sur le plan des bénéfices. Nous avons recours à la méthode expérimentale pour expliquer en quoi cette différence de réaction est, au moins en partie, attribuable à un processus rappelant l’heuristique au moment de la prise de décision par les investisseurs. Point central de notre étude, nous montrons ensuite que, lorsque l’augmentation des revenus explique ne serait-ce qu’une petite partie de la surprise, les investisseurs portent des jugements plus positifs sur l’entreprise concernée que ce à quoi on pourrait s’attendre. Cet effet quelque peu étonnant se produit même lorsque les mêmes investisseurs prévoient des bénéfices similaires pour l’exercice suivant, ce qui indique que nos résultats ne sont pas entièrement attribuables à des jugements différentiels concernant la persistance de la surprise sur le plan des bénéfices. Ces résultats vont dans le sens de l’effet de halo, un phénomène décrit dans la littérature psychologique, selon lequel lorsqu’une personne effectue des évaluations, l’accent qu’elle met sur un facteur prépondérant particulier a une influence sur l’évaluation des autres facteurs. La présente étude aide à expliquer certains éléments complexes du comportement des investisseurs lorsqu’ils évaluent l’impact des changements touchant les revenus et les dépenses. Plus précisément, la préférence des investisseurs pour l’augmentation des revenus par rapport aux réductions des dépenses est partiellement causée par des biais qui ne leur sautent pas aux yeux, de sorte qu’il leur est difficile d’apporter les ajustements requis.

INTRODUCTION

When evaluating a firm to determine what amount one is willing to pay or accept in exchange for shares in that firm, one must consider a multitude of factors. These factors are considered in aggregate to estimate the amount of future cash flows that will come to the individual buying or selling the shares—an important (arguably the primary) consideration for investors. Researchers in accounting have long argued that earnings, as calculated by generally accepted accounting principles, are useful in determining future cash flows (see Ball and Brown 1968 for seminal work in this area). One of the reasons for this correlation is that earnings, including the financial reports that accompany earnings disclosures, can tell us something about the persistence of the revenues and expenses as well as the related underlying cash flows. Thus, we expect that as the persistence of earnings increases, whether that is the result of increased revenues or decreased expenses, investors' judgments about the firm's future prospects will also increase.

One common finding is that changes in revenue are more persistent than changes in expenses (Lipe 1986). While this is not true of all expenses and revenues, if investors instinctively use this as a common rule of thumb (i.e., a heuristic), it could result in suboptimal judgments of firms.

Earnings increases can occur because of increasing revenues, decreasing expenses, or a combination of increasing revenues and decreasing expenses.1 Based on a purely rational approach, using Bayesian updating one might expect that investors are, all else being equal, similarly pleased with a reduction in expenses as with an increase in revenues. However, prior archival research suggests that investors react differently depending on the cause for an increase in earnings (Swaminathan and Weintrop 1991; Ertimur et al. 2003; Ghosh et al. 2005; Gu et al. 2006). Specifically, investors often react more positively when an earnings increase is the result of a revenue increase rather than an expense decrease. While untested, prior research has suggested that the main reason for this differential response is different levels of persistence between expenses and revenues (Ertimur et al. 2003). Though this explanation seems plausible, prior archival work is limited in its ability to examine the actual cause of the differential response. We use an experimental approach to examine potential causes, beyond persistence, for this differential response. Specifically, with a controlled experiment, we can and do establish the level of persistence for revenue and/or expense changes in a firm, and then we examine individual investors' judgments, including looking for causes of any differential judgments that remain after controlling the persistence levels.

In our experiment, we find that nonprofessional investors tend to have more positive evaluations of firms with revenue increases as compared to firms with expense decreases, even when the dollar value changes in earnings (i.e., the increase in revenues or the decrease in expenses) are the same and the persistence of the revenue increase or expense decrease are known to be the same. Further, we find that when firms have earnings surprises caused by a combination of revenue increases and expense decreases, investor judgments regarding the firm's future prospects are similar to judgments when earnings increases are solely caused by revenue increases. Thus, their judgments are more positive than would be expected had they considered the same increase in revenue and decrease in expenses as separate events. In other words, investors seem to fixate on the increasing revenues when making their assessment of the firm's financial performance and not rely on other attributes (in our case, the decreasing expenses) of the cause. Together these findings are consistent with research in psychology regarding associative coherence and the halo effect.

Our results help us better understand investor decisions that seem counter to our economic predictions and could help investors as well as managers develop strategies to avoid potentially poor investment decisions. While we cannot know the optimal investment strategy, when investors insufficiently consider all the causes of an earnings surprise, either by not fully considering implications of expense decreases (because they are focused on the revenue increases, however small they may be) or by automatically assuming revenue increases will persist longer than they will likely persist, these differential judgments can lead to suboptimal investment choices.

We experimentally explore how this heuristic-like process impacts nonprofessional investor judgments when earnings surprises are caused by revenue increases, expense decreases, or both revenue increases and expense decreases. Our results help us better understand why, in many instances, overly optimistic financial forecasts are made by managers, investors, and analysts. This study also contributes to accounting literature on investors' differential reactions to earnings surprises, demonstrating that an additional heuristic-like process may be biasing investor judgments. This knowledge will assist managers to better anticipate investor responses to financial disclosures and aid researchers in predicting and evaluating investment outcomes, and could help investors better understand their investment decisions. Indeed, the stated objectives of IFRS, standards required for all publicly traded corporations in Canada, include providing information to help investors estimate a firm's value and note that it takes time to fully understand how to analyze transactions (IASB 2021). Our study can assist with the stated objectives of international financial standard setters to help investors assess firm value and better understand investor decision-making processes.

THEORY DEVELOPMENT

Earnings announcements have been at the heart of financial accounting research since the seminal paper of Ball and Brown (1968). Earnings surprises occur when the earnings announcement reveals actual earnings that are higher (positive surprise) or lower (negative surprise) than investors' prior expectations. It is well established that earnings surprises are correlated with increases in trading volume and stock price movement consistent with the sign of earnings surprise (Kothari 2001).

Prior research has shown that positive earnings surprises caused by revenue increases are typically valued higher in the market when compared to surprises caused by expense reductions of the same quantitative amount (Ertimur et al. 2003; Swaminathan and Weintrop 1991). While prior research argues that this differential reaction is largely due to persistence—specifically, that investors' preference for revenues is caused by perceptions of higher persistence, we suggest that there may be other biases at play.

There is a robust set of research that examines biases in judgment and decision making related to accounting (e.g., Trotman et al. 2011; Koonce et al. 2011). For example, Elliott (2006) finds that emphasis on pro forma earnings makes the information more salient for nonprofessional investors and causes pro forma disclosures to be overweighted in their judgments. Nelson and Rupar (2015) show that the numerical format used influences investors' risk judgments such that dollar disclosures lead to higher risk assessments than percentage disclosures. Bonner et al. (2014) rely on predictions from mental accounting to explain how investors' judgments are biased based on the aggregation or disaggregation of information on the income statement. Finally, Koonce and Lipe (2017) find that when analyzing a firm with inconsistent performance, investors adopt a simple counting heuristic of how many times a firm meets or misses earnings benchmarks as a proxy for quality. In our study, we continue to explore how biases impact investor judgments by exploring how the earnings characteristics of “revenues” and “expenses” might cause intuitive judgments that may bias investor decisions. We investigate potential impacts of that bias for firms with positive earnings surprises caused by different financial statement characteristics.

As a starting point for understanding investors' differential reactions to increasing earnings that has been demonstrated in prior research, it is useful to consider psychology research regarding how individuals retain and use information about the potential causes for increasing earnings—that is, increasing revenues or decreasing expenses. Morewedge and Kahneman (2010) explain how several features of intuition or quick thinking could contribute to errors in judgment. Important in our investor decision making context is the concept of “associative coherence,” in which when something is recalled from memory there is an automatic association with that memory. For example, investors might associate revenues with positive earnings and expenses with negative earnings. Thus, when investors are asked to evaluate a firm's earnings after being told of revenue increases, the association of revenue (expenses) and favorable (unfavorable) earnings is automatic. Even with more careful processing or attention, individuals are often unable to identify this bias, much less correct for it (Morewedge and Kahneman 2010; Smith and DeCoster 2000).

Some work has been done from a consumer perspective that demonstrates how specific accounting constructs can impact consumer choice. Tian and Zhou (2015) find that consumers make associations with specific accounting constructs when making purchasing decisions. Specifically, consumers see a price increase more favorably when a firm has increased costs rather than when a firm has increased profits. While we are looking at investor decisions, we expect to find that investors will also make automatic associations with the specific accounting constructs of revenues and expenses that will impact their investment judgments and behavior. As investors have an automatic and more positive association with revenues as compared to expenses, this helps to explain prior empirical findings of differential investor behavior for firms with positive earnings surprises caused by revenue increases as compared with expense decreases.

Contrary to the biases discussed above, Bayes' theorem provides a normative model as to how investors should react to a persistent increase in earnings. This theorem is commonly accepted and provides a normative model of belief revision (Beyth-Marom and Fischhoff 1983). Bayes' theorem describes how beliefs (e.g., investor judgments about firms) should change in response to new information. Posterior beliefs—beliefs after the new information has been incorporated—are a function of prior beliefs and how informative or diagnostic this new information is on updating an individual's beliefs (Birnbaum and Stegner 1979). Bayes' theorem is often represented with the following notation: Posterior beliefs = Prior beliefs × Likelihood ratio. Prior beliefs refers to an individual's beliefs before receiving the new information. The likelihood ratio indicates how diagnostic new information is in informing an individual's beliefs and is largely a function of the relevance and reliability of new information. Thus, when information comes from a reliable source and is relevant to a certain belief, the belief will be (according to Bayes' theorem) updated for the new information.

Applying Bayes' theorem to a financial reporting scenario, when investors have reliable information about increases in a firm's earnings, they should update the value of the firm according to how relevant that increase is to future earnings for the firm. Now assume that an investor finds that the increase in a firm's earnings is due to an increase in revenues during the period and that this increase will persist into the foreseeable future. This information would undoubtedly increase the value of the company for the investor. Then consider the same company, showing the same increase in earnings, but it is due to a reduction in expenses. If this expense reduction persists into the foreseeable future, just as the revenue increase was expected to persist, then the investor ought to increase the firm value by the same amount as in the revenue-increasing scenario.2

Prior archival research has suggested that, in general, revenue increases are valued higher in the market as compared to expense reductions of the same quantitative amount (Swaminathan and Weintrop 1991; Ertimur et al. 2003). Explanations from this prior research seem to align this finding with Bayes' theorem by arguing that the most likely reason for the differential response is that there is often greater persistence in revenues as compared to expenses (Ertimur et al. 2003).3 While we agree that credible, relevant information about the persistence of earnings changes in a firm ought to change investor judgments and that differing persistence levels likely explain at least a portion of the differential response shown in the archival research, we theorize that even when no actual differences in persistence exist, investors will employ a heuristic-like process to analyze increases in earnings and favor revenue increases over expense decreases. That is, in this article, we acknowledge that investors will appropriately react differently to earnings of differing persistence, but we explore whether and why investors might continue to have a differential reaction to earnings increases even when controlling for any actual differences in persistence. A differential reaction not attributable to differential persistence would be consistent with psychology research previously discussed (e.g., associative coherence).

Hypothesis 1.When the persistence level of earnings increases are held constant, investors' judgments about an earnings-increasing firm's future prospects will be higher when the increase is due to revenue increases as compared to expense decreases.

If supported, this theory is important as much of the accounting research and prior theory employ economic theories and assume that investors will react in a rational manner (e.g., they use Bayes' theorem to predict investor behavior), but it is often useful to consider other theories of behavior that can help describe and predict investor judgments and decisions (Koonce and Mercer 2005). Understanding when investors are prone to suboptimal investment behavior can highlight circumstances where managers ought to consider additional (or different) disclosures and where investors might benefit from additional analyses.

However, a firm's increase in earnings is often not exclusively attributable to revenue increases or expense decreases, but a combination of the two. So, a reasonable next step is to ask: What might happen in the situation where both revenue increases and expense decreases contribute to a firm's earnings increase? One possibility is that investors will assess the different components separately and their judgments will simply be additive. That is to say, if half of the earnings increase is due to revenue increases and half is due to expense reductions, investor judgments about the firm's future prospects would be equally weighted in their final judgments, resulting in lower (higher) judgments as compared to when the increase is due only to revenue increases (expense reductions). Our findings from Hypothesis 2 will help to examine this possibility.

Research from psychology demonstrates that judgments are often biased by a more holistic evaluation of an item (i.e., an individual or a firm) rather than a more analytical analysis of the specific attributes (i.e., personality traits or specific financial statement items) related to that item as would be done in a purely Bayesian approach (Nisbett and Wilson 1977; Balzer and Slusky 1992). This effect, often known as the halo effect, creates a bias in individuals' judgments because they are using largely nondiagnostic information, or fixating on one aspect to the detriment of another potentially diagnostic aspect, to reach their conclusions. Even when individuals are evaluating specific details, these evaluations are more consistent with their holistic view than would be expected (Murphy et al. 1993).

The halo effect, like associative coherence, relies on associative processes in human cognition (Morewedge and Kahneman 2010). Whereas associative coherence, discussed earlier, describes how a word or concept can be automatically associated with another concept, the halo effect describes how one particular feature of an item might impact—because of the association among the features—the evaluation of the whole item. For example, in our setting, we expect associative coherence when revenues are automatically associated with positive future earnings and the halo effect when earnings surprises are caused by both revenue increases and expense decreases such that investors' firm evaluations are more impacted by one particular cause—the revenue increases.

There is some prior research in auditing (O'Donnell and Schultz 2005), managerial accounting (Jacobs and Kozlowski 1985; Bol and Smith 2011), and marketing (Holbrook 1983) that has demonstrated the impact of the halo effect on auditors, managers, and consumers. However, little prior research seems to have considered this effect on investor decisions. Reimsbach et al. (2018) do find that in some instances, consistent with the halo effect, evaluations of sustainability reports are impacted by favorable financial results. If investor judgments are influenced by the halo effect such that investors' more positive judgments related to revenue increases impact any considerations of the impact of expense decreases, we would expect that investor judgments for earnings-increasing firms where that increase is due to both revenue increases and expense decreases will be similar to (different from) judgments when the increase is due to only revenue increases (expense decreases). This expectation forms the basis for our second hypothesis. Specifically, we theorize that when investors are evaluating firms where there are multiple reasons for earnings increases, they will base their judgments about the firm on the most salient factor (i.e., revenues) rather than an unbiased analysis of each of the causes aggregated to their overall judgments about the firm.4

Hypothesis 2.When earnings increases are explained by both increases in revenues and decreases in expenses, investors' judgments will be higher than when earnings increases are explained by only expense decreases and no different from when earnings increases are explained only by revenue increases.

METHODOLOGY

Experimental Procedure

We test our hypotheses in a 3×1+1 between-participants experiment by manipulating the financial statement line item, which causes the positive change in earnings. We manipulate whether an increase in a firm's earnings was caused by (i) an increase in revenues, (ii) a decrease in expenses, or (iii) an equal combination of revenues increasing and expenses decreasing. We have an additional condition that looks at a combination of revenues increasing and expenses decreasing that is predominantly caused by changes in expenses.

The experiment was administered online using Qualtrics, with participants recruited from Prolific. Participants were asked to assume the role of an investor and were told that they would be making some investment judgments about “Omega Company.” Participants began by reading background information on the company5 and answering three questions about the company. Participants could not advance in the experiment until they correctly answered the three questions. This was done to ensure participants were paying attention to the materials and had an understanding of the company.

After successfully passing the three screening questions, participants were presented an earnings press release (see the Appendix for the experimental materials used). In the press release, participants are informed that the firm had net earnings of $6.25 million for the current year. The press release also provides additional earnings-related information, including earnings guidance the firm had issued earlier in the year ($5.73 million), the difference between actual earnings and their guidance ($0.52 million), and prior year's actual earnings ($5.21 million), all in a table format.6 These additional pieces of information were provided so that participants would readily recognize that the current earnings were higher than two important benchmarks (earnings guidance and prior year's actual), a very positive signal for investors.

Following the table, two bullet points are presented. The first highlights that the current year's “earnings were $0.52 million more than Omega management's previous earnings guidance of $5.73 million.” The second bullet point contains our manipulation. In the Revenue Up condition, the “$0.52 million (net of tax) increase attributed to an unexpected sales increase, which increased gross profit by approximately $0.52 million.” Similar language is used in the Expense Down condition (“…unexpected reduction in costs of approximately…”).7 For the third condition, where both revenue increases and expense decreases cause the increase in earnings, we combine the two to say “…unexpected reduction in costs of approximately $0.25 million and to an unexpected sales increase which increased gross profit by approximately $0.27 million.” We randomized the order of the third condition so that half the participants in this condition were told that costs decreased (revenues increased) by $0.25 ($0.27) while the other half had the numbers reversed.8 For all conditions, the press release concludes with Omega's CEO saying that the reduction in costs, the increase in sales, or both the reduction in costs and the increase in sales are “expected to persist into the foreseeable future.” This design choice is critical to our analysis of how investors react to different financial statement features that have equal levels of earnings persistence. That is, we hold constant the stated level of persistence for the causes of the earnings surprise across all conditions, so that we can examine the reasons for differential investor judgments across conditions not attributable to the known persistence of revenue increases or expense decreases.

After reading the earnings press release, participants were asked to respond to several questions that address their judgments about Omega as an investment. They were asked how attractive they find Omega as an investment (fully labeled 7-point scale: 1 = extremely unattractive; 7 = extremely attractive). Participants were also asked to respond to two questions using a 101-point slider with only the anchors labeled: (i) “What do you think an appropriate common stock valuation for Omega would be?” (0 = low; 100 = high) and (ii) “How desirable do you think an investment in Omega is?” (0 = not at all desirable; 100 = very desirable). We also asked two questions specific to trading behavior. Participants were told that they currently own a diversified portfolio and they are to indicate (i) how likely they would be to buy/sell shares, and (ii) assuming they currently owned 10,000 shares, and had enough cash in reserve to purchase an additional 10,000 shares, how many shares they would buy/sell. Finally, to investigate how participants' estimates of future earnings might explain trading behavior, participants were again shown the table of financial information from the press release and asked to forecast Omega's net earnings for next year.

After these questions related to our main dependent variables, participants responded to some postexperiment questions to better understand the determinants of their investment judgments. Participants responded to questions about how confident they are that the surprise earnings will persist into the future, how risky they find the company, how easy it was to forecast future earnings, and the trustworthiness and competence of the firm's management. Participants then responded to three manipulation check questions before being asked six questions about their beliefs regarding financial statements generally. These general questions relate to the potential explanations provided in prior literature (specifically in Ertimur et al. 2003 and Berger 2003) for why investors react more positively to earnings increases caused by revenue increases as compared to expense decreases.9 Finally, participants were asked for demographic information and, to assess general financial knowledge, they were given one minute to answer five questions (drawn randomly from a pool of 10 financial questions).

Participants

Participants were recruited from Prolific, an online platform designed specifically for academics seeking experimental participants. We use Prolific as this platform has many prescreener questions available to refine the sample of participants who are invited to participate in the experiment. Prior research suggests that data quality using Prolific is equally strong when compared with the more widely cited Amazon Mechanical Turk platform (Peer et al. 2017). For our experiment, we limited our sample to those participants who (i) reside in either the United States or Canada, (ii) speak English as their first language, (iii) have completed at least five previous studies through Prolific, (iv) have an approval rate of at least 98% on previous studies, (v) have made personal investments in common stocks either personally or through their employment, and (vi) when considering a potential investment, they at least sometimes examine the firm's financial statements. Participants were paid £1.00 for roughly 10 minutes of work.10

Seven hundred and sixty people completed the experiment.11 We verified through questions in our demographic section that the majority of our participants had previously made personal investments in the stock of an individual company (90%) and review financial statements at least sometimes when evaluating a potential investment (85%). Participants scored an average of 1.93 out of 5.00 (39%) on the financial knowledge quiz. If adjusted for questions that participants did not answer (which could be due to either not knowing the answer or not having enough time), participants scored an average of 55%. Additional analysis of demographics finds that roughly 63% of our participants are male, the average age is 36, and 70% have full-time employment, while an additional 13% have part-time employment. Seventy-five percent have at least a two-year college degree, while an additional 19% have completed some college. Taken together, there seems to be a good match between our participants' knowledge and experience and the task we would expect nonprofessional investors to be able to carry out (Libby et al. 2002).

RESULTS

Manipulation Checks

We first asked participants to select from a list of options the explanation that best describes the situation they read about (e.g., “A situation where the company experienced significant increases in sales during [the current fiscal year] as compared to [the prior fiscal year]”). Seventy percent of participants correctly answered this question. To assess whether participants accurately responded to the positive earnings and persistence of the line items in the experimental materials, they responded to two questions. First, we asked participants if “Omega's (current) net earnings were” the same as, higher than, or lower than “the company's (prior) net earnings.” Ninety-nine percent correctly recalled that current year's earnings were higher than the prior year's earnings. The second question asked participants if “management indicate that the change in net earnings would persist into the future.” Eighty-four percent correctly recalled that management stated the cause for the change in earnings would persist into the future, with no significant differences in recall across the four conditions. As a secondary measure, we also asked participants how confident they were that earnings would persist into the future. A one-way ANOVA finds no significant difference among conditions (untabulated; p = 0.88, two-tailed). Thus, it appears that our manipulations were successful and that participants largely attended to the details within the experiment. For robustness, we dropped those who failed the manipulation checks and reran all of the analysis, finding no meaningful differences in statistical significance or inferences drawn from the data. Thus, all of our results are presented with data from the entire pool of participants.

Test of Hypotheses

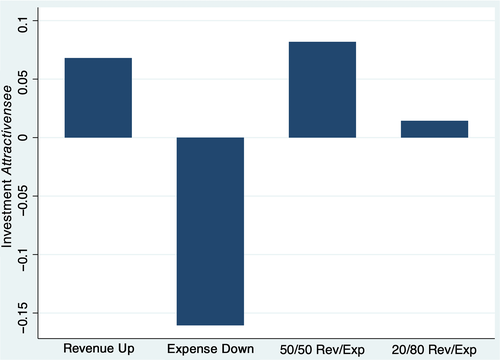

We designed our experiment to test how investors' judgments are informed by their differential reaction to the line item(s) that cause a significant positive earnings surprise. To capture investor judgments, we used five questions with different scale dimensions (7-point fully labeled Likert, 101-point slider with only anchors labeled, 10,001-point slider with anchors and midpoint labeled). We decided to use multiple measures to reduce noise and common measure bias while simultaneously increasing the reliability of our dependent variable. The five questions used include three questions regarding participants' judgments related to the firm being evaluated and two questions related to participants' expected purchasing/selling of the investment. Panel A of Table 1 provides the details of the questions used as well as descriptive statistics for each question. To make comparison feasible between the different measures, we standardize the results. As expected, these five standardized measures are internally consistent (α = 0.85) and thus are averaged together to create one aggregated variable, Attractiveness.12 The bottom of panel A presents descriptive statistics for Attractiveness by experimental condition, while Figure 1 plots the means for Attractiveness by condition.

| Panel A: Questions used to measure investor judgment | |

|---|---|

| Attractive | “How attractive do you find Omega as an investment?” (7-point scale: 1 = extremely unattractive; 7 = extremely attractive) |

| Desirable | “How desirable do you think an investment in Omega is?” (100-point scale: 0 = not at all desirable; 100 = desirable) |

| Valuation | “What do you think an appropriate common stock valuation for Omega would be:” (100-point scale: 0 = low; 50 = average; 100 = high) |

| Likelihood of trading | “For this question, assume that you currently own a diversified stock portfolio. Included in your portfolio are 10,000 shares of Omega stock. Based on the information provided in this case, how likely is that you would buy additional stock in Omega Company or sell stock in Omega Company? (assume that you currently have some uninvested funds available to purchase additional stock, if you wish to do so).” (101-point scale: −50 = very likely to sell; 0 = not at all likely to buy or sell; +50 = very likely to buy) |

| Shares traded | “How many shares of Omega would you buy or sell? (assume that you have enough funds to buy 10,000 additional shares of stock).” (range from –10,000 to +10,000) |

| Panel B: Mean [SD] of investor judgment measures by condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue Up (N = 194) | Expense Down (N = 202) | 50/50 Rev/Exp (N = 203) | 20/80 Rev/Exp (N = 203) | |

| Attractive | 5.701 [0.907] | 5.503 [0.925] | 5.714 [0.958] | 5.738 [0.757] |

| Desirable | 71.549 [14.153] | 67.052 [15.989] | 71.083 [17.004] | 69.733 [16.303] |

| Valuation | 62.873 [16.200] | 58.368 [19.017] | 61.849 [19.851] | 60.911 [19.944] |

| Likelihood of trading | 17.582 [15.027] | 14.295 [16.828] | 18.089 [16.321] | 16.932 [17.134] |

| Shares traded | 2782.473 [2654.756] | 2209.715 [3156.094] | 3114.891 [2970.214] | 2643.105 [2897.121] |

| Attractiveness (average of the standardized variables) | 0.068 [0.712] | −0.161 [0.851] | 0.082 [0.765] | 0.014 [0.795] |

- Notes:

- This table presents descriptive statistics for five questions used to assess participants' judgments about a firm by condition. Because the five measures use different scales, we standardize the scores by mean centering and dividing by standard deviation. We then average the standardized measures into a single variable we call Attractiveness (α = 0.85). We manipulate whether revenue increases, expense decreases, or a combination of both factors contribute to a firm's positive earnings surprise. The first two conditions correspond to earnings being caused solely by revenue increasing (Revenue Up) or expenses decreasing (Expense Down) during the period. We also include two conditions where both revenue and expenses contribute to the change in earnings in a roughly equal proportion (50/50 Rev/Exp) or where revenue is only a small portion and instead the increase is predominantly caused by expenses (20/80 Rev/Exp).

Notes: This figure presents visual evidence of the effect that the cause(s) of a positive earnings surprise has (have) on investors' judgments. The figure presents the means of Attractiveness by experimental condition. The components that were used to construct Attractiveness are defined in Table 1. We manipulate whether revenue increases, expense decreases, or a combination of both factors contribute to a firm's positive earnings surprise. The first two conditions correspond to earnings being caused solely by revenue increasing (Revenue Up) or expenses decreasing (Expense Down) during the period. We also include two conditions where both revenue and expenses contribute to the change in earnings in a roughly equal proportion (50/50 Rev/Exp) or where revenue is only a small portion and instead the increase is predominantly caused by expenses (20/80 Rev/Exp).

The results of a one-way ANOVA are reported in panel B of Table 2. The significant results suggest that investors' judgments are influenced by the financial statement line item causing positive earnings surprises (p < 0.01, two-tailed).13 As stated in Hypothesis 1, we expect investors to have a more positive reaction to increasing earnings that result from an increase in revenue, vis-à-vis a quantitatively similar decrease in expenses. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, pairwise comparisons reported in panel C of Table 2 find that Attractiveness is higher in the Revenue Up condition as compared to the Expense Down condition (p < 0.01, two-tailed). Recall that the earnings increase had the same stated levels of persistence regardless of condition and that, as described with our secondary manipulation check, participants showed no differences in their confidence regarding that stated level of persistence (i.e., that the earnings increase would persist into the future). These findings indicate that investors still make differential judgments regarding firms depending on the cause of the earnings surprise even while levels of earnings persistence are not found to be significantly different. If investors had employed a more Bayesian approach, we would not expect to find any differences between the Revenue Up and Expense Down conditions. Thus, our findings for Hypothesis 1 are consistent with a heuristic-like process where revenues, as compared to expenses, may be automatically associated with more positive future earnings, as predicted by associative coherence.

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics—Attractiveness | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | Mean | SD | |

| Revenue Up | 184 | 0.068 | 0.712 |

| Expense Down | 193 | −0.161 | 0.851 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp | 192 | 0.082 | 0.765 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp | 191 | 0.014 | 0.795 |

| Total | 760 | 0.000 | 0.788 |

| Panel B: One-way ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean squares | F-value | Prop > F |

| Between groups | 7.152 | 3 | 2.383 | 3.89 | 0.009 |

| Within groups | 463.829 | 756 | 0.614 | ||

| Total | 470.981 | 759 | 0.621 | ||

| Panel C: Pairwise comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Std. err. | t | p > |t| | |

| Expense Down vs. Revenue Up | −0.229 | 0.081 | −2.83 | 0.005 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp vs. Revenue Up | 0.014 | 0.081 | 0.17 | 0.864 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. Revenue Up | −0.054 | 0.081 | −0.66 | 0.507 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp vs. Expense Down | 0.242 | 0.080 | 3.04 | 0.002 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. Expense Down | 0.175 | 0.080 | 2.19 | 0.029 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. 50/50 Rev/Exp | −0.068 | 0.080 | −0.84 | 0.399 |

- Notes:

- This table presents descriptive statistics for Attractiveness (panel A) and the results of a one-way ANOVA (panel B) and follow-up pairwise comparison tests (panel C). The components that were used to construct Attractiveness are defined in Table 1. Results are inferentially identical if we use any single component that makes up the Attractiveness variable. We manipulate whether revenue increases, expense decreases, or a combination of both factors contribute to a firm's positive earnings surprise. The first two conditions correspond to earnings being caused solely by revenue increasing (Revenue Up) or expenses decreasing (Expense Down) during the period. We also include two conditions where both revenue and expenses contribute to the change in earnings in a roughly equal proportion (50/50 Rev/Exp) or where revenue is only a small portion and instead the increase is predominantly caused by expenses (20/80 Rev/Exp). Bold values are significant at a minimum of 10%. All p-values are two-tailed.

We turn now to Hypothesis 2. This hypothesis states that, consistent with the halo effect, when both revenue increases and expense decreases cause a positive earnings surprise, investors' perceptions about revenues will impact their overall evaluations of the firm. This will result in investor judgments that are more positive than when only expenses caused the earnings surprise and no different from judgments when only revenue increases caused the earnings surprise. The results in panel C of Table 2 provide support for Hypothesis 2 as the measured Attractiveness is higher in the both Revenue Up and Expense Down condition (50/50 Rev/Exp) than in the Expense Down condition (p < 0.01, two-tailed). We also find no significant differences between the 50/50 Rev/Exp condition and the Revenue Up condition (p = 0.86, two-tailed). Though one should be cautious of overinterpreting a null result, this result—along with a visual inspection of the results suggesting that Attractiveness is even more positive in the 50/50 Rev/Exp condition as compared to the Revenue Up condition—lends support to our Hypothesis 2. If investors had analyzed the impact of the two different causes (i.e., revenue increases and expense decreases) and weighted the proportion of the impact of the causes of the earnings surprise to form their judgments, we would expect to see judgments lower (higher) than when only revenue increases (expense decreases) caused the earnings surprise. Our results are not consistent with this explanation of investor judgments, but rather suggest a bias that is consistent with the halo effect.

To provide an additional test of Hypothesis 2, we employed a fourth condition. In this condition, the earnings increase is again attributable to both revenues increasing and expenses decreasing; however, the change is predominantly due to expenses decreasing. Specifically, the expense decrease accounts for 80% of the total earnings surprise, while the revenue increase accounts for the remaining 20% of the earnings surprise. Similar to the results in the 50/50 Rev/Exp condition, we find that Attractiveness is higher under the 20/80 Rev/Exp condition than the Expense Down condition (p = 0.03, two-tailed) but is not statistically different from the Revenue Up condition (p = 0.51, two-tailed). Additionally, the Attractiveness ratings in 20/80 Rev/Exp condition was not statistically different from ratings in the 50/50 Rev/Exp condition (p = 0.40, two-tailed). These findings are consistent with our Hypothesis 2 and lend more robust support for our predictions based on the halo effect. That is to say, even when the proportionate share of the earnings surprise is skewed toward expense decreases, investors' judgments (i.e., Attractiveness assessments) are similar to when only revenue increases cause the surprise. The impact of the revenue increase appears to influence investor judgments as much when it is one of two causes of a positive earnings surprise as when it is the only cause.

Finally, to provide added support suggesting that it is investors' attitudes toward revenues and expenses, not differences in actual persistence levels of revenues versus expenses, that result in differential investment judgments, we asked participants to forecast next period's earnings. If investors believed that revenue increases were more persistent than expense decreases, one would expect that their earnings forecasts for the next period would differ across conditions. Descriptive statistics for the earnings forecast are reported in panel A of Table 3. A one-way ANOVA (panel B; p = 0.43, two-tailed) and follow-up pairwise comparison (panel C) do not reveal any significant differences between conditions (smallest p = 0.16, two-tailed).14 Thus, it appears that the cause of the current year's earnings surprise (i.e., a revenue increase, expense decrease, or both) does not affect investors' expectations about next period's performance (i.e., forecast of next year's earnings), yet has a significant influence on how attractive the firm is as an investment. Again, this finding is consistent with a bias to unknowingly evaluate earnings surprises caused by revenue increases (even if revenue increases represent a small proportion of the surprise) more favorably than similarly persistent surprises caused by expense decreases.

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics—Earnings Forecast | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | Mean | SD | |

| Revenue Up | 184 | 6.845 | 2.131 |

| Expense Down | 193 | 6.798 | 1.765 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp | 192 | 6.582 | 1.604 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp | 191 | 6.641 | 1.667 |

| Total | 760 | 6.716 | 1.799 |

| Panel B: One-way ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | SS | df | MS | F-value | Prop > F |

| Between groups | 8.891 | 3 | 2.964 | 0.92 | 0.433 |

| Within groups | 2448.267 | 756 | 3.238 | ||

| Total | 2457.158 | 759 | 3.237 | ||

| Panel C: Pairwise comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Std. err. | t | p > |t| | |

| Expense Down vs. Revenue Up | −0.047 | 0.185 | −0.25 | 0.799 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp vs. Revenue Up | −0.263 | 0.186 | −1.42 | 0.157 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. Revenue Up | −0.204 | 0.186 | −1.1 | 0.273 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp vs. Expense Down | −0.216 | 0.183 | −1.18 | 0.239 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. Expense Down | −0.157 | 0.184 | −0.85 | 0.393 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. 50/50 Rev/Exp | 0.059 | 0.184 | 0.32 | 0.747 |

- Notes:

- This table presents descriptive statistics for Earnings Forecast (panel A) and the results of a one-way ANOVA (panel B) and follow-up pairwise comparison tests (panel C). Participants are asked to forecast earnings for the next year after learning that the current (prior) earnings were $6.25 million ($5.21 million). We manipulate whether revenue increases, expense decreases, or a combination of both factors contribute to a firm's positive earnings surprise. The first two conditions correspond to earnings being caused solely by revenue increasing (Revenue Up) or expenses decreasing (Expense Down) during the period. We also include two conditions where both revenue and expenses contribute to the change in earnings in a roughly equal proportion (50/50 Rev/Exp) or where revenue is only a small portion and instead the increase is predominantly caused by expenses (20/80 Rev/Exp). All p-values are two-tailed.

Additional Analysis

Part of our original motivation in running an experiment was to consider the explanations posed by Ertimur et al. (2003) to describe why investors react more positively to revenue increases versus expense decreases. These three explanations were related to persistence (i.e., revenue is less transitory than expenses), homogeneity (i.e., revenues have less variation in form, whereas expenses can vary dramatically), and earnings management (expenses are easier to manipulate and harder to detect than revenue manipulations). However, as Berger (2003) notes in his discussion of Ertimur et al. (2003), the homogeneity argument seems to be more an extension of persistence than an alternative. Further, we posit that earnings management could also largely be seen as an extension of persistence because when a manager manipulates earnings it impacts both current and future earnings, thus altering the persistence of the firm's earnings. A typical self-serving manipulation of earnings is to present earnings as higher than the actual earnings. This lowers persistence of any earnings surprises caused by earnings management, as the artificial inflation of actual earnings cannot persist indefinitely.

One benefit of the experimental method is that we can control for and ask questions specific to alternative explanations that are often confounded in naturally occurring data (i.e., stock prices). Because most valuation models rely on estimates of earnings persistence, it would make sense that this is a large driver of the differential reactions observed in prior research. Within our experiment, we told all participants that the financial statement line item(s) causing the earnings increase is (are) “expected to persist into the foreseeable future.” As detailed previously, we also asked participants to indicate their confidence in the persistence of the earnings surprise as well as to project next year's earnings. Neither of these measures show significant differences across conditions, suggesting that the persistence of the earnings surprise in the experiment was not impacting investor judgments of the firms.

However, it may be true that participants' judgments were impacted by differential attitudes about revenues or expenses in general. We attempted to address this concern by asking participants to “think generally about financial statement items and the preparation of financial statements.” Participants then answered questions asking about persistence and earnings management for both revenues and expenses to test explanations given in prior literature (Ertimur et al. 2003). Table 4, panel A, provides the details of the questions and panel B presents the results of an OLS regression using participants' responses to the questions as the independent variables and Attractiveness as the dependent variable. Results show that, indeed, investor beliefs about revenue persistence do vary across condition in a pattern that suggests participants' evaluations of the persistence of revenues, in general, were impacted by our experimental manipulation (p < 0.01, two-tailed).

| Panel A: Questions used to measure investor beliefs | |

|---|---|

| Persist | “How likely is it that revenues (expenses) will persist into the future?” (7-point scale: 1 = extremely unlikely; 7 = extremely likely) |

| Difficult | “How difficult do you think it is for management to manipulate reported revenues (expenses)?” (7-point scale: 1 = extremely easy; 7 = extremely difficult) |

| Discovered | “How likely is it that revenues (expenses) which have been manipulated will be discovered by investors?” (7-point scale: 1 = extremely unlikely; 7 = extremely likely) |

| Panel B: OLS regression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue Up (N = 194) | Sig. | Expense Down (N = 202) | Sig. | 50/50 Rev/Exp (N = 203) | Sig. | 20/80 Rev/Exp (N = 203) | Sig. | |

| Persist revenue | 0.429 | *** | 0.294 | *** | 0.332 | *** | 0.387 | *** |

| [0.054] | [0.062] | [0.054] | [0.063] | |||||

| Persist expense | 0.011 | −0.007 | 0.011 | 0.050 | ||||

| [0.039] | [0.045] | [0.038] | [0.043] | |||||

| Difficult revenue | −0.088 | * | 0.024 | − | * | −0.043 | ||

| [0.049] | [0.062] | [0.059] | [0.058] | |||||

| Difficult expense | 0.061 | −0.081 | −0.120 | ** | −0.004 | |||

| [0.050] | [0.063] | [0.058] | [0.057] | |||||

| Discovered revenue | 0.012 | 0.024 | 0.007 | 0.029 | ||||

| [0.051] | [0.065] | [0.056] | [0.067] | |||||

| Discovered expense | −0.051 | −0.016 | −0.010 | 0.004 | ||||

| [0.050] | [0.065] | [0.057] | [0.071] | |||||

| Constant | −2.074 | −1.518 | −1.579 | −2.251 | ||||

| [0.405] | [0.484] | [0.390] | [0.417] | |||||

| Adj. R2 | 0.2820 | 0.1129 | 0.1868 | 0.2130 | ||||

- Notes:

- This table presents alternative explanations for investor behavior observed in Ertimur et al. (2003). Panel A details the questions used to assess participants' beliefs. Panel B is the results of a regression of these six questions on Attractiveness by condition. We manipulate whether revenue increases, expense decreases, or a combination of both factors contribute to a firm's positive earnings surprise. The first two conditions correspond to earnings being caused solely by revenue increasing (Revenue Up) or expenses decreasing (Expense Down) during the period. We also include two conditions where both revenue and expenses contribute to the change in earnings in a roughly equal proportion (50/50 Rev/Exp) or where revenue is only a small portion and instead the increase is predominantly caused by expenses (20/80 Rev/Exp). Bold values are significant at a minimum of 10%. All p-values are two-tailed. *, **, and *** constitute p-values of 0.10, 0.05, and 0.01, respectively.

Given this pattern of results, we perform additional analysis to test our hypotheses using participants' general perceptions of both revenue and expense as covariates in our model. Though participants were asked to think more generally in responding to these questions, and participants' evaluation of the persistence of the earnings surprise have not varied significantly across conditions, these responses may help us better understand how perceptions of the persistence of revenue increases and expense decreases can impact firm Attractiveness. Table 5 includes the results of this analysis. When using the general persistence ratings as covariates, we still get results consistent with our main findings. That is, we still find significant differences in the Attractiveness measure between the revenue increasing condition and the expense decreasing condition (p < 0.05, two-tailed) as well as between each both revenue increasing and expense decreasing condition and the only expense decreasing condition (p < 0.10, two-tailed). This further strengthens our assertion that there is a previously unexplained portion of variance beyond differences in persistence that can be attributed to positive associated attributions of the underlying accounting construct of revenue vis-à-vis expenses.

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics—Attractiveness | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | Mean | SD | |

| Revenue Up | 184 | 0.068 | 0.712 |

| Expense Down | 193 | −0.161 | 0.851 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp | 191 | 0.079 | 0.766 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp | 190 | 0.014 | 0.798 |

| Total | 758 | 0.000 | 0.788 |

| Panel B: ANCOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | SS | df | MS | F-value | Prop > F |

| Condition | 3.909 | 3 | 1.303 | 2.63 | 0.049 |

| Revenue persistence | 81.504 | 1 | 81.504 | 164.78 | >0.001 |

| Expense persistence | 0.517 | 1 | 0.517 | 1.05 | 0.307 |

| Residual | 371.948 | 752 | 0.495 | ||

| Panel C: Pairwise comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Std. err. | t | p > |t| | |

| Expense Down vs. Revenue Up | −0.154 | 0.075 | −2.06 | 0.040 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp vs. Revenue Up | 0.042 | 0.073 | 0.58 | 0.565 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. Revenue Up | −0.031 | 0.073 | −0.43 | 0.669 |

| 50/50 Rev/Exp vs. Expense Down | 0.195 | 0.073 | 2.69 | 0.007 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. Expense Down | 0.122 | 0.073 | 1.68 | 0.093 |

| 20/80 Rev/Exp vs. 50/50 Rev/Exp | −0.073 | 0.072 | −1.02 | 0.310 |

- Notes:

- This table presents descriptive statistics for Attractiveness (panel A) and the results of an ANCOVA (panel B) and follow-up pairwise comparison tests (panel C). The components that were used to construct Attractiveness are defined in Table 1. Results are inferentially identical if we use any single component that makes up the Attractiveness variable. We manipulate whether revenue increases, expense decreases, or a combination of both factors contribute to a firm's positive earnings surprise. The first two conditions correspond to earnings being caused solely by revenue increasing (Revenue Up) or expenses decreasing (Expense Down) during the period. We also include two conditions where both revenue and expenses contribute to the change in earnings in a roughly equal proportion (50/50 Rev/Exp) or where revenue is only a small portion and instead the increase is predominantly caused by expenses (20/80 Rev/Exp). We include as covariates participants' perceptions of revenue persistence and expense persistence, as defined in Table 4. Total observations in this analysis are less than our total observations in our main analysis found in Table 2 as two participants failed to provide responses for all the general questions related to persistence. Bold values are significant at a minimum of 10%. All p-values are two-tailed.

Together, our analysis in Tables 4 and 5 provide some indirect evidence for our halo effect explanation. That is, the halo effect would predict that investors' judgments for firms with both revenue increases and expense decreases are the same as judgments from firms with only increasing revenues, and we find, consistent with this explanation, no significant impact of reported levels of the persistence of the expense decreases and the Attractiveness measure. This is consistent with investors' focusing on revenue increases and not on expense decreases in making their firm evaluations, even when both factors have significant impact.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we examine investor reactions to positive earnings surprises when they are caused by increasing revenues, decreasing expenses, or by a combination of increasing revenues and decreasing expenses. We identify a heuristic-like process that can bias investor judgments in unexpected ways. While prior research suggests that the differential reaction to positive earnings surprises caused by increasing revenues versus decreasing expenses is caused mainly by different levels of persistence, in our study we leverage the strengths of the experimental method to control for persistence levels. We find that, even when controlling for actual persistence in the earnings surprise, investors have a stronger reaction to revenue increases vis-à-vis expense decreases. While this differential reaction would be unexpected with a Bayesian-like information processing system, these findings are consistent with a heuristic-like process (e.g., associative coherence; Morewedge and Kahneman 2010) in which investors assess revenue increases as more positive when compared to expense decreases even though they have an identical impact on current earnings or on investors' estimates of future earnings.

Further, we demonstrate that when an explanation for earnings involves both revenue increases and expense decreases (a common feature for many earnings-increasing firms), investor judgments appear statistically identical to judgments when only revenue increases caused the earnings surprise. This suggests that the favorable judgments related to revenue are effortlessly applied to the entire earnings surprise, consistent with a finding in psychology research known as the halo effect (Balzer and Slusky 1992). This finding persists even when revenue increases make up a much smaller proportion of the earnings surprise.

These findings are important as they help us further understand how investors react to financial reports. It suggests that investors often focus on one item or are unknowingly impacted by a specific cause even when multiple relevant impacts are present, potentially to the detriment of their decision-making process. While it is difficult to ascertain the economic impacts of this effect in an experimental setting, the findings in this article help to explain some of the complexities with individual investor behavior when considering how they evaluate financial statement items. Specifically, investors' preference for revenue increases as compared to expense decreases, even in the presence of both impacts, may be caused by cognitive biases that are likely not obvious to the decision maker.

Our study deepens our understanding of why investors often have differential reactions to earnings components and can help explain investor reactions to other relevant information (e.g., a firm's financial reports and managerial disclosures). With an increased understanding of the biases that impact financial statement users, future researchers can develop better models of investor behavior and, while we cannot ascertain the optimal or normative reaction to these disclosures in this study, further study could help managers understand the potential negative impacts of this bias and then, hopefully, prepare disclosures to minimize those impacts.

In considering the results of our study, several limitations should be noted. These limitations provide future research opportunities. First, we hold constant the persistence of earnings, when in reality the persistence of earnings varies between firms and within years. Future research might examine how differing persistence levels would moderate the observed results. Second, we provided participants with only a portion of the information that would generally be available when making investment judgments. We contend that more information should not significantly alter the direction or strength of the associative coherence bias or halo effect observed in our results. Nonetheless, future research may consider providing participants with additional sources of information, such as analyst reports.

Third, we only consider a scenario where an earnings surprise is positive; however, earnings surprises can also be negative (i.e., unexpected decreases in revenue and/or unexpected increases in expenses). We purposely did this to be consistent with prior archival research in the area (e.g., Ertimur et al. 2003) and also because there is a documented asymmetrically stronger reaction to positive versus negative earnings surprises (e.g., Bartov et al. 2002; Pinello 2008). Thus, it is possible that other mechanisms present in a negative earnings surprise situation, such as the negativity bias, may overshadow the effects of associative coherence and the halo effect. Future research will want to explore if there is an asymmetrically negative reaction to revenue decreases versus expense increases as the driver of a negative earnings surprise.

Fourth, in their analysis, Ertimur et al. (2003) distinguished between growth and value companies and find that the differential reaction to earnings surprises driven by revenue vis-à-vis expense changes is stronger for growth than value firms. Our experiment does not provide explicit information to distinguish whether the firm is a growth or value company. However, some information is given in the background materials (e.g., one of the largest manufacturers in their industry) that suggests the company is mature. Future research could manipulate the company life cycle to see how this affects investors' positive biases toward revenues.

Endnotes

APPENDIX: Experimental Materials15

Omega Reports 2018 Results

(BUSINESS WIRE) — October 25, 2018 — Today Omega released earnings for the year ended August 31, 2018. The Company reported net earnings of $6.25 million. Details of Omega's conference call are outlined below:

| 2018 actuals | Previous earnings guidance for 2018 | Increase of actual earnings relative to previous guidance | 2017 actuals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net income | $6.25 million | $5.73 million | $0.52 million | $5.21 million |

- 2018 net earnings were $0.52 million more than Omega management's previous earnings guidance of $5.73 million.

-

(Revenue Up): $0.52 million (net of tax) increase attributed to an unexpected sales increase which increased gross profit by approximately $0.52 million.

- Dan Athens, Omega's CEO, said that “the increase in sales is expected to persist into the foreseeable future.”

-

(Expense Down): $0.52 million (net of tax) increase attributed to an unexpected reduction in costs of approximately $0.52 million.

- Dan Athens, Omega's CEO, said that “the reduction in costs is expected to persist into the foreseeable future.”

-

(50/50 Rev/Exp): $0.52 million (net of tax) increase attributed to an unexpected reduction in costs of approximately $0.27 million and to an unexpected sales increase which increased gross profit by approximately $0.25 million.

- Dan Athens, Omega's CEO, said that “both the reduction in costs and the increase in sales are expected to persist into the foreseeable future.”

-

(20/80 Rev/Exp): $0.52 million (net of tax) increase attributed to an unexpected reduction in costs of approximately $0.42 million and to an unexpected sales increase which increased gross profit by approximately $0.10 million.

- Dan Athens, Omega's CEO, said that “both the reduction in costs and the increase in sales are expected to persist into the foreseeable future.”

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.