Aboriginal patients driving kidney and healthcare improvements: recommendations from South Australian community consultations

The authors have stated they have no conflicts of interest.

Abstract

Objective: To describe the experiences, perceptions and suggested improvements in healthcare identified by Aboriginal patients, families and community members living with kidney disease in South Australia.

Methods: Community consultations were held in an urban, rural and remote location in 2019 by the Aboriginal Kidney Care Together – Improving Outcomes Now (AKction) project and Kidney Health Australia. Consultations were co-designed with community members, using participatory action research, Yarning, Dadirri and Ganma Indigenous Methodologies. Key themes were synthesised, verified by community members and shared through formal and community reports and media.

Results: Aboriginal participants identified the importance of: family and community and maintaining their wellbeing, strength and resilience; the need for prevention and early detection that is localised, engages whole families and prevents diagnosis shock; better access to quality care that ensures Aboriginal people can make informed choices and decisions about their options for dialysis and transplantation, and; more Aboriginal health professionals and peer navigators, and increased responsiveness and provision of cultural safety care by all kidney health professionals.

Conclusion: Aboriginal community members have strong and clear recommendations for improving the quality and responsiveness of health care generally, and kidney care specifically.

Implications for public health: Aboriginal people with lived experience of chronic conditions wish to significantly inform the way care is organised and delivered.

The health care needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have unique elements that require a specific response. While the challenges of living with chronic illnesses and needing to travel to receive care are also experienced by some non-Indigenous peoples, the additional impacts of colonisation, racism, intergenerational trauma, marginalisation and the socio-cultural determinants of health experienced by many Indigenous peoples are important considerations.1

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people often experience health impacts of illnesses such as kidney failure from a younger age, while still studying, working and raising children.2 Across Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are five times more likely to start dialysis than non-Indigenous Australians with kidney failure rates 10-30 times higher in remote areas.2-4 Within South Australia (SA), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people represent two per cent of the total population, with 97% of this group identifying as Aboriginal, and 30% residing outside of Adelaide.5 Specialised healthcare is located in major cities, requiring many people to leave their homes and families to receive lifesaving treatment.

Health and kidney care services are increasingly recognising that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people must be actively involved in designing new models of kidney care that meet their clinical and cultural needs.6 Previous SA studies have mapped individual kidney care journeys, identifying specific barriers and enablers in communication, collaboration and care.7-9

In 2018, the Aboriginal Kidney Care Together- Improving Outcomes Now (AKction) project brought together Aboriginal kidney patients and community members, health professionals, health service managers, decision makers, academics and researchers to identify gaps and strategies to improve kidney care in SA.10 An AKction Reference Group (ARG) comprising Aboriginal patient experts and family members was established and supported by the AKction research team. The ARG and research team worked closely with Kidney Health Australia (KHA), the Central Northern Adelaide Renal and Transplantation Service (CNARTS) and other local community members to co-design and co-facilitate consultations in a metropolitan, outer regional and very remote location within SA. Working in partnership,11, 12 meaningful Indigenous Governance, respectful collaboration, cultural safety13 and ‘reimagining’ gold-standard kidney care, underpinned this approach.

In this study we sought to include wider Aboriginal patient, family and community voices, and ensure their experiences and priorities influenced policies, guidelines and health service priorities and structures. Consultations were co-designed to inform local, jurisdictional and national health care, the writing of inaugural Kidney Health Australia (KHA) and Caring for Australians with Renal Impairment (CARI) Guidelines,14 and local and national initiatives involving Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry ANZDATA,15 Kidney Health Australia14 and the National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce.16

Methods

This paper reports on the findings of the consultations; the emerging themes and feedback from community members regarding current care experiences and suggestions for improvement. In South Australia, the First Nations contributors identify as Aboriginal Australians and prefer the term Aboriginal is used when referring to community members involved in the AKction project.

Study design, setting and participants

Participatory action research comprising repeated cycles of ‘look and listen, think and discuss and take action together’8 was used to build relational networks and conduct the consultations in urban, rural and remote locations. ARG members, CNARTS and Aboriginal health staff, KHA staff and AKction researchers contacted Aboriginal renal patients, community members and regional health professionals to discuss the best consultation venues, timing around dialysis, transport support, catering and approaches to recruitment to maximise involvement. All of these groups were involved in recruitment using emails, verbal invitations, telephone calls, flyers in health services, dialysis centres, hostels and support services.

Consultations were held in a major city, outer regional and very remote location across South Australia where the AKction project had existing relationships and ethics cover. Sites included: Kanggawodli Aboriginal medical hostel in Adelaide December 2018, Pika Wiya Aboriginal Health Service in outer regional Port Augusta in February 2019 and very remote Ceduna Hospital in June 201917 (see Table 1). Participants (Aboriginal kidney care patients, family members, other community members who are carers) self-selected whether to attend consultations, on which days and for how long. Transport assistance was provided and sessions were timed around people's dialysis schedules as much as possible. The Kanggawodli consultation included both Aboriginal people who lived in Adelaide and Aboriginal people from rural and remote areas staying at the hostel while receiving specialist care for a range of health conditions. Health professionals adopted a support and listening role in all consultations, in a similar model to that used in Indigenous Patient Voices6 and Catching Some Air consultations.18

Location, date and details of location |

Aboriginal patients, carers and family member participants |

Co-facilitation & support roles |

|---|---|---|

Major City: Adelaide Kanggawodli Aboriginal hostel November 2018 1 day workshop Metropolitan Adelaide has multiple hospital based, outpatient and satellite dialysis services. |

18 Aboriginal patients, family members and carers from urban, rural and remote locations & one non-Aboriginal carer. This includes 2 AKction Reference Group members who both contributed and co- facilitated the consultation. |

1 Renal AHP who co-facilitated 10 non-Aboriginal attendees including 3 researchers/co-facilitators, 2 renal nurses, 3 nephrologists, 1 EO NIKTT, 1 student. |

Outer Regional: Port Augusta Pika Wiya Aboriginal Health Service February 2019 2 day workshop Port Augusta regional hospital has a 12 chair unit and provides dialysis for 27 Aboriginal patients (which is nearly a third of all 95 Aboriginal people receiving dialysis in SA) ANZDATA Pers Comm Dec 2020) |

17 Aboriginal patients, family members and carers from rural and remote locations. This includes 1 AKction Reference Group member who contributed, co- facilitated and interpreted throughout the consultation. |

1 Renal AHP who co-facilitated 11 non –Aboriginal attendees including: 4 researchers/co-facilitators, 1 local dialysis manager/renal nurse, 3 visiting nephrologists, 1 CEO KHA, 1 EO NIKTT, 1 Pika Wiya health professional. |

Very Remote: Ceduna Hospital June 2019 2 day workshop Ceduna Hospital has a 2 chair dialysis unit providing dialysis for remote area patients. |

10 Aboriginal patients, family members and carers from Ceduna and nearby remote communities. |

1 Renal AHP and 1 Aboriginal researcher who co facilitated 3 local AHPs. 9 non-Aboriginal attendees including 3 researchers/co-facilitators, 1 local dialysis manager/renal nurse, 1 visiting nephrologist, 1 DON/CEO of Ceduna Hospital, 1 local nurse, 1 NIKTT EO, 1 renal coordinator) |

- Notes:

- Further details can be found in each community consultation report available on Kidney Health Australia website https://kidney.org.au/get-involved/advocacy/yarning-kidney-consultations

- AHP: Aboriginal Health Practitioner/Professional

- EO: executive officer, NIKTT – National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation taskforce.

- CEO KHA: Chief Executive Officer, Kidney Health Australia

Data collection – consultation methodology

Each consultation began with a Welcome to Country by a Traditional Custodian and an introduction to the purpose and methodology led by the research team. Written participant consent for participation, audio recordings, identification in reports and photography was obtained. Indigenous methodologies: Yarning,19, 20 Dadirri deep listening21 and Ganma knowledge sharing22 were used with prompt questions (see Table 2) in semi-structured focus groups. Community participants were invited to share their experiences of care and suggestions for improvement. Smaller round table discussions were facilitated by researchers and/or local health care providers (as participants preferred), followed by larger, whole group discussions. Conversations were recorded, and/or notes taken, as preferred by individual participants.

Questions |

|---|

|

1. What is your experience with kidney disease? a. What did you know before having kidney disease – did it come as a surprise? Prompt questions for facilitators What did people know before having kidney disease – did it come as a surprise for them? How could people's understanding of kidney disease, access to kidney care, and experiences of dialysis and transplantation be improved? |

2. How could kidney care may be made better for you and your community? a. Access b. Information c. How and where care is provided? Prompt questions for facilitators What other supports are needed (for example transport and accommodation, peer support, resources). How could information about kidney disease and kidney care be improved? What would help improve; prevention of kidney disease, early detection of kidney disease, access to dialysis and health care, kidney care and transplantation, and cultural safety. |

3. What are the best ways to communicate health messages and share information? Prompt questions for facilitators What would be the best ways to communicate kidney health messages to patients and their families and communities? (health education) |

4. We teach doctors and nurses – what do we need to make sure we teach them about caring for you? Prompt questions for facilitators Staff communication, cultural awareness and cultural safety, responsiveness, appropriateness How do people feel in interactions with staff? |

Data analysis

Key themes were identified, contextualised and prioritised by community members in a whole-group discussion at the end of each consultation workshop, ensuring community participation in early analysis and prioritisation. All butcher's paper and group facilitation notes were transcribed written into site specific reports, checked by ARG and approved by participants in location to ensure accuracy, truth telling and community control.17 Permission to include names and images was sought from each participant, or family members if a participant passed away, and each participant or family representative received a final version. All raw data was then collated by two non- Indigenous researchers using NVivo 10 software. Emerging themes from prompt questions were combined to form the coding tree. Results were discussed with research team and reference group members.

Ethics approval was provided by the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (#04-18-796, the University of Adelaide (ID: 33394) and Central Adelaide Local Health Network (HREC/19/CALHN/45).

Results

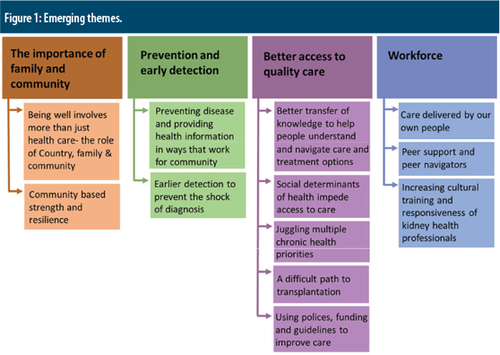

A total of 46 Aboriginal community members and 37 health professionals, managers, coordinators and researchers (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal) participated (see Table 1). Findings are reported to highlight community priorities and responses to the ‘prompt questions’ and are organised under four themes: The importance of family and community; Preventing and detecting kidney disease early; Better access to quality of kidney care; and, Workforce (see Figure 1). These themes reflect the concerns and priorities identified by Aboriginal patients, family and community members (participants). Participant quotes are identified by location of consultation: major city (MC), outer regional Australia (OR) or very remote (VR) (19) to highlight commonality and difference of experiences and suggestions across locations in South Australia. Strategies to address each of these themes, as suggested by participants, are summarised in Table 3.

Emerging themes.

Theme 1:Recognise the importance of families and communities |

Recognise the vital role of family, community and Country

|

Recognise community based strengths and resilience

|

Theme 2:Work with us on preventing and detecting kidney disease early |

Help prevent kidney disease by increasing kidney health information

|

Earlier detection of kidney disease

|

Theme 3:Kidney care our way – improve our access and the responsiveness of care |

Support us to access care in ways and places that we need

|

Recognise that what impacts our lives, impacts our ability to access kidney care

|

Recognise that we are juggling multiple health priorities

|

Improve the path to transplantation for patients, and support our families

|

Focus your policies, funding and guideline writing on what is important for us

|

Theme 4: Workforce |

We want to see more Aboriginal people in the workforce and receive care delivered by our own people

|

We need peer support and peer navigators

|

Increase cultural training and responsiveness of all renal health professionals

|

Theme 1: The importance of family and community

Being well involves more than just health care – the role of Country, family, community

It's difficult to keep our spirits up without spending time on Country and with our family and loved ones. (OR)

Going back to the bush is good for the heart and mind. (VR)

Many people come from home communities where we are leaders and have important roles and responsibilities. When we have to leave that behind to access treatment in the city …, we feel like rubbish, and we are treated like [these things] are unimportant. (MC)

We moved here to support my uncle, but we need just as much support to know what we should be doing. (VR)

Community based strengths and resilience

We have to stop this dependence on other people to solve problems, people need to be empowered. (VR)

Now my illness (kidney disease) is more under control, I want to get back to work. (OR)

Many identified that while clinical staff and support services play a crucial role in treating kidney disease, community members provide advocacy, cultural support, empowerment and leadership.

Theme 2: Prevention and early detection

Preventing disease and providing health information in ways that work for Community

Kids gotta understand that you need to be healthy now to be healthy. (VR)

Getting into schools, raising awareness and getting kids thinking about their kidneys and how to keep them healthy. (OR)

Hold events that bring the community together to learn about keeping themselves healthy, [such as] cooking or health check days. (VR)

We need more information about what is happening, where to go for help and when to do this. (OR)

There are materials in Italian, Greek and other languages, but there is nothing in our languages – yet we are the Traditional owners of the land. (MC)

Earlier detection to prevent the shock of diagnosis

We don't know when it is best to get further information or a ‘kidney health check’, or even how to do this. (OR)

I only knew what to look out for after seeing other family members with the same thing. (OR)

Aboriginal Medical Services only focus on one disease, but do not include kidneys, dialysis, diabetes, etc. – they could be teaching about other organs while teaching about the eyes or something. (MC)

Earlier detection also enables discussion of options and preparation before treatment or dialysis began.

I was shocked when the doctor rang me to say I should start dialysis the next day. (MC)

When my kidneys are sick, I can't think straight. (OR)

When I found out my kidneys were sick, I didn't want to listen to the doctors, information just went in one ear and out the other. (VR)

Kidney failure is scary, we know that it can be a death sentence or mean that you'll be stuck on dialysis for the rest of your life. (MC)

Theme 3: Better access to quality care

Better transfer of knowledge to help people understand and navigate care and treatment options

I want to know more about [the medications] I am taking, about dialysis and my options. (OR)

I know someone who used the bag [peritoneal dialysis]… they kept getting infections. It was no good. (VR)

Is peritoneal dialysis something I can have? I don't know. (OR)

Social determinants of health impede access to care

Some people are homeless. (all locations)

A lot of people are in hardship, the pension isn't enough, if we have to pay to travel there isn't enough left to get food. (OR)

Unless you are in the big hospital, you don't get the services. (VR)

That is when depression starts because you don't know what is happening. I used to work, but I don't anymore, I was exhausted, tired. Sunday was my only day off, because I attended dialysis for 5/6 hours a day, three times a week. (OR)

I never know what hospital I will be going to or whether I will be in the morning or afternoon, they just ring and say the transport will be here in 20 minutes, it makes it impossible to do anything else with my day. (MC)

I am a country man, I need to be able to move and travel to keep myself healthy. (Remote)

As if the pain from the kidney machines isn't bad enough, we already broken hearted from being away from home. (OR)

We can't go home, we can't go anywhere, we get trapped. (MC)

Juggling multiple chronic health priorities

They could come to us while we are on dialysis. (MC)

A difficult path to transplant

They just told me that I had to lose weight to stay on the transplant list, not how much weight or why just that I had to. (MC)

There's a real panic, must always have your phone on and charged and in reach, can't let the grandkids play with it in case they decline that call. (OR)

I put off going for transplant two times when I got the call, because I had heard from other community members how scary it was. (OR)

I was told you better say goodbye before surgery, just in case they (live donor and recipient family members) don't come out – as a family we were offered no support, I felt useless like I wasn't a part of the journey. (OR)

Using policies, funding and guidelines to improve care

Cancer council have a bus and a hostel, I have stayed there before when my sister was sick, why can't we have something like that too? (OR)

Participants identified the importance of ensuring the inaugural CARI clinical guideline included more comprehensive information about the way health care can be organised and delivered to better support their wellbeing, address risk factors and challenges, and increase family-based decision making. Community members wished to be involved throughout the writing and implementation processes to ensure that the final guidelines appropriately represented their needs and priorities and could bring positive change.

Theme 4: Workforce

Care delivered by our own people

We should educate our young people, they could become nurses and doctors and go back to community and work in renal care. (MC)

… our own people, working here, living here… not different people coming and going. (VR)

Increased access to interpreters to address miscommunication and confusion, as well as informed consent was also identified.

Peer support and peer navigators

I reckon [Aboriginal lived-experienced kidney patient] sharing her experience would be good – hearing about what other people have gone through would be really helpful. (MC)

The hospital should employ an [Aboriginal person with lived of kidney disease] to explain to Aboriginal people about dialysis and what is a kidney transplant, and the consequences of these treatments. (MC)

Increasing cultural training and responsiveness of renal health professionals

People don't need to know specifics, they just need to be aware that diversity is out there and that it needs to be acknowledged. (OR)

Moving to Adelaide is confusing, it is very different from the country. You have to learn about the buses and where the supermarkets are, all that extra stuff. (OR)

They sought support to remain connected to their culture and communities whilst undergoing treatment, for some, doing painting and artwork while on dialysis helped.

Discussion

The process undertaken by AKction ARG and research team members, CNARTS and KHA to co-design community consultations has enabled Aboriginal patients, families and community members to discuss their experiences of kidney care and identify specific clinical, social, cultural and cultural safety priorities, gaps and strategies. The consultation process developed in SA has been used to inform the remaining KHA consultations around Australia.17 Similarly, NIKTT have utilised used the ARG and consultations processes to form Indigenous Reference groups and consultations nationally,24 enabling kidney care services to more effectively partner with consumers.11, 25

The consultation reports, verified by participants and shared with local, jurisdictional and national health services, have triggered kidney care changes within in South Australia, including the piloting of dialysis chairs in an Aboriginal hostel. AKction subsequently held two key stakeholder workshops focusing on transport and accommodation, Aboriginal workforce and dental care.

The themes emerging in these consultations reflect those reported in many other Australian kidney care studies over the last fifteen years, including: the importance of family and community15, 26 and their inclusion in care and discussions,26-28 the need for (improved) communication, prevention and earlier detection,15, 26-29 the impacts of social determinants of health15, 26 and juggling multiple chronic health priorities,26 and the need for increased support to access to quality care,26, 27, 29 improvements in the pathway to transplantation15, 16, 28; and the need for more Aboriginal workforce15, 26, 28, 29 and improved cultural safety of staff and services.15, 26, 28 The suggestions of using policies, funding and guidelines to improve kidney care was also raised in the three Catching Some Air project sites - Darwin, Alice Springs and Thursday Island (18). This study, strengthens the findings of previous study, strengthening the argument for change. It provides localised examples and ensures that the voices of Aboriginal people from South Australia can also directly inform the new national clinical guidelines, and national agenda for improving kidney care.

Limitations

While recognising that these consultations with self-selected participants in three locations do not reflect all experiences and diversity of all Aboriginal South Australians, shared concerns were raised in each location indicating common elements across communities. Transport and language interpretation were provided to improve access and equity, and consultations were timed around dialysis sessions as much as possible, but some potentially interested participants could not attend. The pre-determined prompt questions may have limited discussion; these questions were reviewed following each consultation in response to community feedback, and wider, community-driven discussions were encouraged at each consultation. The consultation was a learning process. The research team were largely non-Indigenous and included clinicians new to two-way learning and participatory action research approaches. Participating in workshops increased their personal and cultural awareness and critical reflection, and introduced them to decolonising concepts. Aboriginal community members with lived experience of kidney disease and Aboriginal health professionals co-planned and co-facilitated the consultations and small group discussions, ensuring the processes and settings were culturally welcoming and appropriate.

Conclusion

These consultations reinforce the value of community leadership to inform tangible changes and improvements in health care generally and kidney care specifically. When Aboriginal patients are recognised as experts in their own care, the unique, complex and multidimensional insights they and their families provide are invaluable. They can comprehensively inform local, jurisdictional and national health care co-design, policies, guidelines and standards. Meaningful involvement of Aboriginal people in the co-creation of care is necessary to ensure health knowledge and care is accessible, effective and responsive to needs.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Aboriginal patients, families and participants who shared their experiences of kidney care, and strategies for improvement. Dora Oliva was significantly involved in planning, facilitating and evaluating two of the workshops with community members, and drafting reports. We also thank the health professionals and support service staff from Kanggawodli Hostel, Port Augusta Dialysis Unit, Pika Wiya Aboriginal Health Service and Ceduna District and Aboriginal Health Services, who assisted in the planning, facilitation and logistics of each consultation.

Penny Smith provided critical review of the manuscript.

This project was funded by a Health Translation SA Rapid Applied Research Translation for Health Impact Grant through the Medical Research Future Fund, and Kidney Health Australia.

The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.