What does it cost to feed aged care residents in Australia?

Abstract

Aim

Funding cuts to the aged care industry impact catering budgets and aged care staffing levels, which may in turn affect the nutritional status of aged care residents. This paper reports average food expenditure and trends in Australian residential aged care facilities (RACFs).

Methods

This is a retrospective study collecting RACFs’ economic outlay data through a quarterly online survey conducted over the 2015 and 2016 financial years.

Results

Data were compiled from 817 RACFs, representing 64 256 residential beds and 23 million bed-days Australia-wide. The average total spend in Australian Dollars (AUD) on catering consumables (including cutlery/crockery, supplements, paper goods) was $8.00 per resident per day (prpd) and $6.08 prpd when looking at the raw food and ingredients budget alone. Additional data from over half the RACFs (n = 456, 56%) indicate a 5% decrease in food cost ($0.31 prpd) in the last year, particularly in fresh produce, with a simultaneous 128% ($0.50 prpd) increase in cost for supplements and food replacements. Current figures are comparatively less than aged care food budgets internationally (US, UK and Canada), less than community-dwelling older adults ($17.25 prpd) and 136% less than Australian corrective services ($8.25 prpd).

Conclusions

The current spend on food in RACFs has decreased compared with previous years, reflecting an increasing reliance on supplements, and is significantly less than current community food spend.

Introduction

The quality of residential aged care services is an area of regular scrutiny that will undoubtedly continue in the face of increasing funding cuts.1, 2 Aged care providers have been facing reduced profits when comparing 2016 with 2012 figures and face increasing difficulties when working within a funding system that is prescriptive in terms of government funding.3 Financial cuts impact catering budgets and staffing and in turn may affect the nutritional status of aged care residents.4, 5 Specific to aged care, research suggests that cost cutting reduces quality care, whereas focus on quality care can improve cost savings.6-8 This is further supported by data from developed countries indicating that total food spend is associated with more nutritious dietary patterns.9

With malnutrition affecting at least one in two residents in Australian residential aged care facilities (RACF),10, 11 it is only natural to turn attention towards obvious causes for this concerning statistic. Malnutrition is associated with a cascade of adverse outcomes, including increased risk of falls,12 pressure injuries13 and hospital admissions,14 leading to poorer resident quality of life15 and increased health-care costs.16, 17 Diminished sensory perception along with the physiology of ageing may increase malnutrition risk.18 However, there is emerging evidence that food insecurity or the limited ability to access adequate, safe, tasty, nutritious and culturally appropriate food may also be implicated in the aetiology of malnutrition in residential aged care.19 Ever-tightening aged care budgets may be impacting food insecurity and food spends and should not be overlooked as part of the problem.

The purpose of this paper is to report current data regarding the average expenditure on ingredients and food in Australian RACFs.

Methods

This was a retrospective study set across RACFs in Australia using data collected using a pre-set survey. This pre-set survey conducted by a well recognised aged care accountancy firm1 was developed to provide insights into the financial performance of RACF providers. Participants self-subscribe to be part of the quarterly survey and submit their data every quarter, with many completing the survey on a quarterly basis since 2001.

The Lantern Project, a national collaboration of aged care industry stakeholders,20 focused on improving the quality of life of RACF residents through good nutrition, partnered with the aged care accountancy firm to further investigate the economic value of nutrition. In the past 2 years, in response to work with The Lantern Project, the accountancy firm has requested further details in their survey around catering costs to better understand the food spend.

This paper reports the care costs related to catering—including crockery, cutlery—and now, more specifically, raw food, ingredients and oral nutritional supplement costs. Results from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2016 are presented in this paper. Results are sorted into bands to acknowledge the diversity of residents represented according to care income and acuity of resident mix (Band 1 = highest care needs, Band 5 = lowest care needs).

Data were collected via an emailed survey, including an excel spreadsheet for completion by the aged care provider. Data were then imported into the accountancy firm's proprietary database. Survey reports are distributed to clients via a secure website. The reports are provided to them in both Excel and PDF format. These reports are provided at RACFs and compare their data with an appropriate set of benchmarks. The survey gives comparisons that providers can choose to filter and compare by—including options such as comparing against the top providers in the country (top 25%), comparing against the top 50% and comparing against similar size facilities. All data provided in reports are of an aggregated nature in PDF format.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee, which provided ethical approval for the study (project no. 0000016021). The survey collects corporate financial data and does not collect any information of a private or personal nature. As part of the accountancy firm's terms and conditions, only de-identified data were provided to ensure the confidentiality of all client information. Terms of the survey give the firm permission to publish in this format.

Data were recorded and analysed using Microsoft Excel 2010. Averages of total money spent on catering consumables were calculated and presented as column graphs.

Results

The survey was completed by 817 RACFs across Australia with the results representing 64 256 residential places (beds) (33% of the operational places nationally) with around 23 million bed days of data. The breakdown of RACFs and residential places (beds) in Australia state by state is as follows: 357 RACFs in NSW (28 251 places), 15 RACFs in ACT (1305 places), 142 RACFs in QLD (11 865 places), 84 RACFs in Victoria (6635 places), 120 RACFs in South Australia (8880 places), 70 RACFs in WA (4958 places), 1 RACF in Northern Territory (65 places) and 28 RACFs in Tasmania (2297 places).

On average, AUD$8.00 was spent per resident per day (prpd) from 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016. The amount spent from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015 was AUD$7.52 prpd. These amounts include the cost of food and cooking ingredients, supplements, meal replacements and other items such as crockery, cutlery and paper goods.

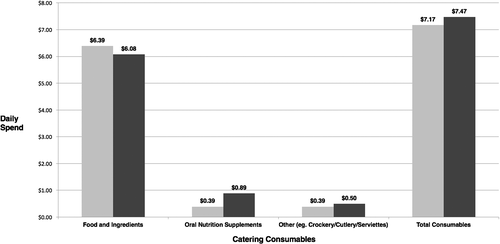

Over half the aged care providers (n = 456, 56%) provided further detail of the breakdown of catering consumables on food and ingredients, which decreased by AUD$0.31 prpd (4.9% decrease in food costs) to AUD$6.08 prpd (Figure 1). Of these facilities, there were increases in oral nutrition supplements and food replacements of AUD$0.50 prpd (128% increase) and in other consumables (predominantly a mixture of crockery, cutlery and paper products) of AU$0.11 per bed day (28%).

) and 2016 (

) and 2016 ( ).

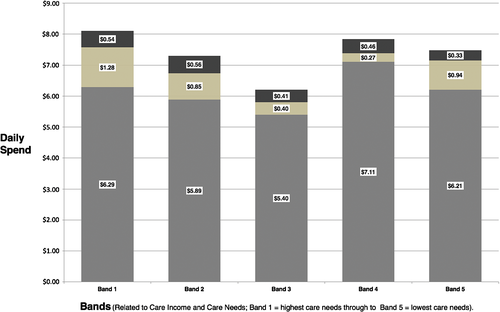

).The survey breaks down costs according to resident care needs in the past 12 months (July 2015 to June 2016 period) (Figure 2). Band 1, representing residents with the highest care needs, showed the highest average total spend per day, with AUD$6.29 prpd on food and ingredients and the highest average spend on oral nutrition supplements and other food replacements, whereas Band 3 showed the lowest spend in terms of food and ingredient costs at AUD$5.40 prpd.

) Other—crockery, cutlery, paper products; (

) Other—crockery, cutlery, paper products; ( ) oral nutrition supplements; (

) oral nutrition supplements; ( ) food and ingredients.

) food and ingredients.Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to present a snapshot of the amount Australian RACFs are spending on food and ingredients. This paper therefore provides a foundation for future benchmarking.

Current average food and ingredient budgets in Australian RACFs are trending downwards, with a $0.31 prpd decrease in the last 12-month period, and appear to be significantly lower than food budgets in the Australian community, correctional services and internationally.

To contextualise the current food and consumables budgets for aged care residents, a comparison against food budgets elsewhere has been explored. Raw food funding prpd mandated in Ontario, Canada (as of July 1st, 2016) is $8.33 Canadian Dollars ($8.63 AUD)21—increasing 49.6% over the 2007–2016 period, with audits around nutritional analysis demonstrating the need for food budget increases during this period.22 In England, weekly food payments are £26 in 2013 (£3.70 prpd—AUD$6.12 prpd), increasing 12.8% over 2008–2013. Norwegian aged care budget figures show food costs, which included food, supplements and labour, averaged to 102.18kr prpd (AUD$20.41 prpd) in 2007 and increasing to 128.4kr prpd (AUD$22.86 prpd) in 2013—increasing 25.7% over the 2007–2013 period. The average daily food cost according to a US food service census in aged care (Long-Term Care) facilities was US$6.61 prpd (AUD$8.98 prpd) in 2014—up slightly from US$6.59 prpd in 2013.23

The increase in supplements and food replacements in the present paper likely indicates that aged care providers perhaps choose supplements over fresh food and ingredients in response to unintentional resident weight loss. Given the ongoing high rates of malnutrition in Australian RACFs and potentially improved awareness of the issue despite an increased supplement spend, we are clearly not solving the expensive problem of malnutrition with current approaches. Strathmann demonstrated the relationship between food budget and malnutrition risk in 2013.5 While increasing choice and food quality appears a logical strategy and the benefits of the ‘food first’ approach have been documented,24-26 this study demonstrates that ‘let fresh food be thy medicine’ is perhaps not the adage currently followed in the Australian aged care industry.24-26

Increasing the aged care profit margin by reducing food spend impacts the quality of resident care and can contribute to malnutrition rates in aged care. A recent study completed by the authors (Hugo, Isenring) has demonstrated a reversal of trends in supplement use, and an increase in food-first strategies has not only led to improved quality of life measures for aged care residents but improvements in weight and overall nutritional status and with savings in terms of food budgets (unpublished data).

The results in this study show a reduction in food spend in aged care over the past 12 months despite inflation figures, suggesting food costs in the community to be increasing over time when looking at items such as fresh fruit, vegetables and meals out.27

As per the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2014), in the general community, adults younger than 35 years spend approximately AUD$18.29 per person on food and drinks daily.28 Young couples (average age 28 years) were the highest spenders, with AUD$23.60 per person per day being spent on food and drinks. Older couples were found to be more frugal, spending AUD$17.25 per person on food and drinks daily,29 which is still nearly thrice that of the current aged care food budget. While cost may be considered related to higher macronutrient requirements amongst younger age groups, the difference is not proportional to the significant variation in budget. Older couples living the community are likely to have similar energy and protein needs to residents living in RACFs.

Australian Corrective Services currently spend $8.25 per prisoner per day—136% more than the RACF current figures. According to policy, ‘the prison system's custodial responsibility requires inmates receive a diet sufficient to maintain them, while its public responsibility means that this must be done on a minimal budget’.30 Even at its minimal value, the budget for food per prisoner per day exceeds the average budget prpd in Australian RACFs.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that aged care food budgets have decreased despite inflation, reflecting increases in fresh produce in the community over this time. On a per resident basis, RACFs are currently spending nearly 1.4 times less than the current food budget for prisoners and nearly three times less than the Australian average of older adults living in the community. Current Australian RACFs spends are also well below comparative aged care food budgets internationally when compared to Canada (1.4 times less), Norway (3.8 times less) and the US (1.5 times less). The costly burden of malnutrition is highest in the Australian RACF setting and will not be helped by ongoing reductions in food spend. Discussions through advocacy groups, such as The Lantern Project, with the government around mandating minimum food budget spends similar to that seen in Canada along with improved RACF nutrition education and promotion of cost neutral strategies to improve nutritional value of meals within budgetary constraints are suggested as a positive move in response to this paper. Future research should explore whether other health outcomes improve with an increase in food spend.

Funding source

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Authorship

This study was conceptualised by CH and DS. DS collected the data. DS, CH, EA and LI analysed and interpreted the data. CH compiled the original manuscript. EA, LI and DS contributed towards the manuscript revision. All authors approved the final manuscript.