Do people feel they belong? Socio-political factors shaping the place attachment of Hong Kong citizens

Abstract

Hong Kong citizens’ sense of belonging has gone through a period of fluctuation during the period of rapid socio-political and legal change since the outbreak of the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement in 2019. This study explored how multiple dimensions of the place attachment of Hong Kong citizens have been shaped by factors associated with these changes. Six socio-political variables were incorporated into the three dimensions of the person–process–place (PPP) framework. Based on a representative survey of the local population (n = 768), we found that political inclination and identity were significantly associated with the sense of place, with citizens identifying as Chinese and aligning with the pro-establishment camp showing higher levels of place attachment. Mobility was negatively associated with place attachment, whereas the correlation between attachment and perceptions of the law and legal system was positive. The study has implications for Hong Kong’s current socio-political and institutional environment and for emigration. It also demonstrates the wider applicability of the PPP framework for identifying and clarifying the various predictors of different dimensions of place attachment.

Key insights

The associations between the place attachment of Hong Kong citizens and six socio-political factors were explored using a person–process–place framework. Citizens with a pro-establishment political stance and self-identifying as Chinese showed a higher level of attachment. Those with a greater degree of mobility who perceived inequalities in society showed a lower level of attachment. Those holding more positive views about the law and legal system of Hong Kong showed a higher level of attachment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hong Kong people have, for a long time, been in a state of identity ambivalence. Their Chinese identity grew during the 2000s, with the visit of China’s first astronaut in 2003 and the 2008 Beijing Olympics, among other things (Fung & Chan, 2017). In the momentous year of 2019, their recognition of local (Hong Kong) identity reached its highest level in 30 years, before dropping drastically at the end of the same year (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2021). This trend of a fading recognition of local identity and belongingness may very well point to similar changes in the place attachment of Hong Kong people. The decline took place during a period of rapid socio-political change, with the outbreak of the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement in 2019, followed by the implementation of the Hong Kong National Security Law in July 2020. The influence of drastic and significant socio-political changes on the place attachment and belongingness of people has been documented (Kam, 2021; Ranta & Nancheva, 2019). For instance, there was a reported shift in the belonging patterns of European Union nationals residing in the United Kingdom (UK) towards their European identity when the UK left the European Union (Ranta & Nancheva, 2019). Locally in Hong Kong, Kam’s (2021) study of previous social movements, such as the Umbrella Movement, also suggested that such events and the associated local developments induced changes in Hong Kong people’s sense of place (Kam, 2021).

The status of Hong Kong as a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the People’s Republic of China, attained after its return to Beijing in 1997 following over 150 years of British rule, has generated much attention to and debate over issues related to its citizens’ identity (Lin, 2021). Studies of people–place bonds in Hong Kong have generally focused on identity and emotional attachments (Jang et al., 2021; Kuah-Pearce & Fong, 2010; Ma & Fung, 2007; Mathews et al., 2007). But the place attachment of Hong Kong people has always been complex. Their nuanced relationships with Mainland China arguably allowed them to separate their emotional attachment with the “motherland”—historically and culturally defined—from the political embodiment of the same nation whose political ideology they do not necessarily favour (Lui, 2019). This schizophrenia reveals itself, for example, when Hong Kong people were to choose between the “local” (Hong Kong) and the “national” (China) in international sporting events where both teams are present (Wu, 2020).

Although people–place bonds have been studied in the context of Hong Kong through the use of concepts or factors relevant to place attachment, such as belongingness and sense of community, the broader concept of place attachment has rarely been adopted (Chan et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021; Kuah-Pearce & Fong, 2010). The under-utilisation of this concept reflects a general problem regarding studies of people–place bonds, which have tended to define the relevant concepts using varying features and dimensions across disciplines. For example, some scholars have used the broader term of place attachment whereas others have adopted more traditional concepts such as belongingness, sense of community, or sense of place (Scannell & Gifford, 2010). To address the amorphous definition of place attachment and the lack of a coherent framework that captures the various aspects of people–place bonds of interest to multiple fields, such as sociology, geography, and environmental psychology, Scannell and Gifford (2010) developed the three-dimensional person–process–place (PPP) framework, encompassing the actor (person), psychological processes (process), and the object of place attachment (place). Alongside the advantages of its multidimensional structure, the PPP framework was designed with reference to all of the literature on place attachment and thus combines classic and recent findings, making it more integrative and inclusive than most other models. The application of this simple yet inclusive framework can help to guide the development of quantitative instruments and make studies more applicable and comparable (Scannell & Gifford, 2010).

To our knowledge, few studies on the case of Hong Kong have focused on the concept of place attachment. Instead, existing literature has generally explored the connection of people to place through concepts associated with place attachment, such as belonging, sense of community, and sense of identity (Chan et al., 2020, 2022; Guo et al., 2021). For example, Guo et al. (2021) adopted a physical perspective on place attachment and found that features of the local built environment, including vegetation and the availability of health facilities, influenced the sense of community of Hong Kong residents. To study the social and behavioural dimensions of place attachment, Chan et al. (2020) adopted a social and behavioural perspective to explore the associations between belongingness, schooling experience, and educational mobilities among Chinese cross-border students in Hong Kong. They found that better social relationships and higher levels of engagement in extra-curricular activities were associated with higher levels of belongingness. Kuah-Pearce and Fong (2010) adopted a cognitive perspective to explore the development of a sense of identity and belongingness in Hong Kong secondary school students and discussed how the education reforms implemented after the resumption of the People’s Republic of China’s sovereignty over Hong Kong might have shaped students’ choices and development of identities. These studies have provided in-depth discussions of a range of concepts and topics relevant to place attachment, but in the absence of a common systematic framework, their findings cannot be compared directly and their approaches are difficult to replicate. To address this issue, this study integrates and harmonises the various concepts and definitions of place attachment found in extant literature.

This study locates identity and emotion within the PPP framework. We argue that identity and emotional attachment organically run through all the three dimensions of the PPP framework. For example, one’s identity is often built and nurtured by the values and symbols collectively upheld (such as rule of law, civil liberties, and collective social actions)—the “person” dimension—as well as by the sense of community generated by social interactions and the social-natural environments therein—the “process” dimension (Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001; Manzo, 2005). Likewise, emotional attachment is closely related to the “process” dimension as emotion can be easily triggered by the collective beliefs and/or memories shared by people being present at a particular place and time (Jorgensen & Stedman, 2001; Scannell & Gifford, 2010).

This article contributes to the emerging literature on identity in Hong Kong, for which a theoretical framework for the construction of the concept is lacking. It also raises theoretical and practical implications on the building and governance of place attachment on the people in an era of rapid socio-political change. While adopting an established model on place attachment, this article illuminates the subtle nature of the concept and how various socio-political factors come to influence Hong Kong people’s sense of attachment to this “hybrid” city (Chan, 2013).

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 The PPP framework

This study builds on the three-dimensional PPP framework (Scannell & Gifford, 2010) and applies it to explain place attachment in Hong Kong. As a theoretical framework designed to approach the concept from several distinct theoretical approaches (sociology, geography, psychology, and so on), it is ideal here as local attachment is shaped by a set of diverse factors as the discussion above showed. In their recent belongingness study, Jang et al. (2021) suggested that factors closely associated with the socio-political turmoil in 2019, including concerns over governance, democratic development, legal reforms and law enforcement, and financial insecurity, might have contributed to the lower level of belongingness identified among youth in Hong Kong. Given the complexity of the case of Hong Kong, the multidimensional PPP framework is therefore suitable for exploring the different ways that socio-political factors relevant to the recent developments have shaped or re-shaped citizens’ place attachment. The application of the PPP framework also helps to reveal and differentiate the varying effects of different dimensions of place attachment.

Extant literature features a range of models for conceptualising and giving structure to place attachment, albeit with a more limited coverage and applicability as the PPP framework. For instance, Woldoff (2002) conceptualised place attachment mainly through social connections and interactions, resulting in a model that emphasises social ties within the community and neglects the potential influence of the physical and social features of place. Similarly, Sense of community, as suggested by McMillan and Chavis (1986), provides a framework to understand attachment within the physical and social aspects of communities, yet it remains insufficient in clearly distinguishing the different dimensions of place attachment. Likewise, Shumaker and Taylor (1983) model posits affect as the major psychological process in people–place bonding and therefore does not recognise the behavioural and cognitive aspects of the psychological processes of developing place attachment. As compared with these studies, the PPP framework brings together a range of theoretical insights with a three-dimensional framework. It is argued that the framework (and our suggested model) is more comprehensive and theoretically-driven than existing ones on place attachment since it accommodates different factors and suggests concrete measures for each dimension, as well as supporting it with empirical data.

2.2 Dimensions of the PPP framework

In this section, we discuss the three dimensions of the framework with reference to our study. First, the person dimension of the PPP framework describes the actor that develops and perceives an attachment to a place (Scannell & Gifford, 2010), which can be a single individual perceiving meaning, a group of individuals holding a collective meaning, or a combination of both. Individual attachment denotes a personal connection to a place. For individuals, the meanings of a place can be created from important experiences and are related to the personal characteristics of the individual and the characteristics of the place. At the group level, place attachment describes how members of a group, which can be cultural or religious, attach similar symbolic meanings to a place because they share a history, values, symbols, beliefs, practices, or a sense of sacredness (Scannell & Gifford, 2010).

The second dimension of the PPP framework is the process dimension, which refers to the ways that individuals connect to a place and the associated psychological processes, namely, the affective, cognitive, and behavioural interactions, that foster such a connection (Jorgensen & Stedman, 2001). The affective aspect of place attachment concerns the emotional connection of an individual to a place and is often described as the positive emotions that a place provides to those who feel connected or the negative emotions associated with displacement (Giuliani, 2003; Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001; Manzo, 2005). From a cognitive perspective, place attachment refers to the processes, such as the construction of memories, beliefs, and knowledge, that allow an individual to create meanings and form connections with a specific place (Scannell & Gifford, 2010). The behavioural aspect of psychological processes comprises the actions that create and maintain connections between individuals and places and is typically expressed and discussed in terms of proximity-maintaining behaviours (Hay, 1998; Kasarda & Janowitz, 1974). Literature has studied the various types of behaviour that allow an individual to stay close to a place, such as efforts to return home, to minimise the frequency of trips away from home, or to adjust the length of residence (Hay, 1998; Riemer, 2000).

The third dimension of the PPP framework encompasses the features and characteristics of the place to which connections are formed. Place attachment has often been categorised into social and physical forms (Riger & Lavrakas, 1981). Social place attachment generally refers to the social bonding between people that is facilitated by a place acting as an arena for social interactions. It can be represented by, for example, belongingness to a community or interpersonal relationships with other residents (Perkins & Long, 2002; Pretty et al., 2003; Woldoff, 2002). The social features of a place or society, such as the socio-political environment and people’s cultural backgrounds, can also influence the development of attachments by contributing to the construction of meanings associated with a place (Lynnebakke & Aasland, 2022). Physical place attachment is the meaning that individuals attach to the physical features of a place (Stedman, 2002), which can take various forms such as physical structures and architectural styles, the natural environment, or even the climate (Knez, 2005; Manzo, 2003, 2005).

2.3 Applications of the PPP framework

Scannell and Gifford (2010) recommended the use of the PPP framework for both quantitative and qualitative studies. For quantitative applications, Scannell and Gifford (2010) suggested that the framework could be useful for developing measurement instruments for place attachment studies, comparing the effects of different dimensions and levels of place attachment, and investigating the cause-and-effect relationships between specific factors and place attachment. This approach is useful for isolating and comparing dimensions and levels of place attachment because it helps to clearly identify the factors associated with different types of place attachment. For example, Garavito-Bermúdez and Lundholm (2017) examined the attachment of fishers to local ecosystems through the process and place dimensions of the PPP and demonstrated that both the fishers’ understanding of the place and the social and cultural features of the place were associated with positive emotions and proximity-maintenance behaviours. Another study examining place attachment in outdoor recreation contexts showed that different aspects of the psychological dimension of place attachment had various effects on place attachment (Kyle et al., 2004). The current study further expands its application by suggesting factors measuring each dimension and testing it empirically.

The exploration of causes and effects is a more common approach to studying place attachment and involves testing the influences of various factors or predictors on different dimensions of place attachment. For instance, focusing on the person dimension, Marney (2012) explored the level of place attachment of citizens in rural Missouri by considering the potential influence of personal characteristics, and Wahyudie et al. (2020) used the physical aspects of the place dimension to explore the connections of people to religious-based built environments and how this physical place attachment developed. However, existing studies seldom examine the different dimensions simultaneously as we do in this research.

3 METHOD

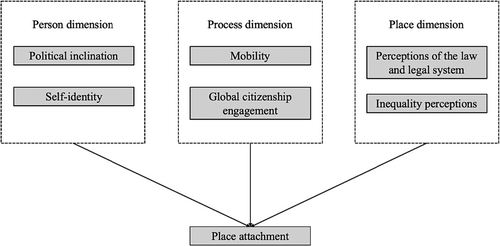

To determine the influence of socio-political factors on people’s place attachment, two independent variables were chosen to represent each of the three dimensions of the PPP framework (Figure 1). Each factor was considered carefully to determine which dimension (person, process, or place) it should be assigned to. As the three dimensions of the PPP framework are interconnected, a variable assigned to one dimension may also be relevant to another. The relevance of particular variables to multiple dimensions is discussed in the subsections for each dimension.

The main dependent variable in our study, place attachment, was measured using seven items pertaining to the three dimensions (Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001; Scannell & Gifford, 2010). On a 5-point Likert scale, the respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Example items are “All the things in Hong Kong represent me” and “I want to stay in Hong Kong instead of moving elsewhere.” The items and the scores are provided in Table 1. The place attachment variable for each respondent was calculated as the average response to the seven items, with a higher score indicating a greater place attachment to Hong Kong. All items in this variable were adopted from a questionnaire on place attachment developed and validated in previous studies (Jorgensen & Stedman, 2001; Ramkissoon et al., 2012; Williams & Vaske, 2003).

| Item | % | M | Cronbach’s alpha | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |||

| Place attachment | 3.48 | 0.800 | |||||

| Q1. All the things in Hong Kong represent me. | 14.0 | 17.3 | 21.3 | 26.0 | 21.5 | 2.76 | |

| Q2. I can truly be myself when I am in Hong Kong. | 31.2 | 28.3 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 12.1 | 3.52 | |

| Q3. I am proud of being a Hong Konger. | 43.2 | 27.5 | 15.2 | 8.4 | 5.6 | 3.94 | |

| Q4. I want to stay in Hong Kong instead of moving elsewhere. | 40.3 | 25.2 | 13.9 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 3.75 | |

| Q5. I enjoy living in Hong Kong. | 35.4 | 29.8 | 16.1 | 11.0 | 7.7 | 3.74 | |

| Q6. There are other places that are more suitable for living than Hong Kong. (R) | 33.6 | 29.7 | 10.6 | 12.6 | 13.5 | 2.43 | |

| Q7. I miss Hong Kong when I am away. | 51.3 | 32.0 | 9.0 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 4.23 | |

| Inequality perceptions | 4.32 | 0.725 | |||||

| Q8. Differences in income in Hong Kong are too large. | 53.7 | 33.8 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 4.32 | |

| Q9. The disparity between the rich and the poor in Hong Kong has grown in the past 5 years. | 55.2 | 31.9 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 4.32 | |

| Perceptions of the law and legal system | 2.97 | 0.905 | |||||

| Q10. The law protects the rights of people in power rather than those of ordinary citizens. (R) | 24.7 | 23.4 | 17.0 | 17.7 | 17.3 | 2.8 | |

| Q11. People in power use the law to try to control ordinary citizens. (R) | 29.2 | 21.8 | 13.7 | 15.9 | 19.4 | 2.74 | |

| Q12. The law protects the interests of all citizens. | 20.4 | 22.3 | 19.1 | 17.7 | 20.4 | 3.05 | |

| Q13. The law is made through a fair procedure. | 22.2 | 26.8 | 16.8 | 13.1 | 21.1 | 3.16 | |

| Q14. Judges generally deliver reasonable judgements. | 15.4 | 28.7 | 21.4 | 17.6 | 16.8 | 3.08 | |

| Always | Often | Sometimes | Seldom | Never | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global citizenship engagement | 2.06 | 0.621 | |||||

| Q15. Keeping up with global affairs by reading international news. | 15.1 | 44.4 | 23.7 | 7.3 | 9.5 | 3.48 | |

| Q16. Donating to international non-governmental organisations for global causes. | 1.9 | 5.9 | 16.2 | 17.6 | 58.4 | 1.75 | |

| Q17. Joining activities that enhance understanding and welfare of ethnic minorities. | 0.6 | 1.8 | 9.5 | 21.3 | 66.7 | 1.48 | |

| Q18. Doing things (e.g., recycling at home or buying second-hand products) for environmental purposes. | 5.9 | 27.7 | 36.0 | 14.8 | 15.7 | 2.93 | |

| Q19. Being a member of a non-governmental organisation for a global cause. | 0.1 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 5.9 | 91.0 | 1.13 | |

| Q20. Using online or social media to participate in global social movements (anti-poverty, human rights, democracy, anti-human trafficking, etc.). | 0.4 | 4.3 | 13.8 | 14.5 | 67.0 | 1.57 | |

| Mobility | |||||||

| Q21. How often did you travel internationally before the social movements in 2019 and COVID-19? | 2.0 | 17.9 | 34.9 | 21.3 | 23.9 | 2.53 |

| Self-identity | Chinese | Hong Konger in China/Chinese in Hong Kong | Hong Konger | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q22. Do you identify yourself as a …? | 14.9 | 35.4 | 49.7 | ||||

| Political inclination | Pro-establishment | Centralist | Pro-democracy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q23. Which option best matches your political orientation? | 25.1 | 6.8 | 68.1 | ||||

- Abbreviation: R, reverse coded.

3.1 The person dimension

Two variables were adopted to capture the socio-political experience and characteristics of Hong Kong citizens: political inclination and self-identity. A study in Hong Kong before the socio-political changes in 2019 suggested a connection between people’s political inclinations and their local attachment (Lo et al., 2021). That again suggests that the meaning of a place is a product of the characteristics of both an individual and the place, as well as the experiences they co-generated, such as political activism. This study therefore portrays self-identity as a way in which the respondents position themselves within the spectrum of local and national identities. To measure political inclination, we used a three-category scale of pro-democratic, centralist, and pro-establishment inclinations (with a higher figure indicating a more pro-establishment stance). Self-identity is another core issue in place attachment and has been adopted in the literature as both a measurement and a predictor of place attachment (Qazimi, 2014; Sampson & Goodrich, 2009). In our survey, self-identity measured the respondents’ recognition of their identities at the local and national levels. Three options were provided to represent local, local and national, and national identities: “Hong Konger,” “Hong Konger in China/Chinese in Hong Kong,” and “Chinese,” respectively.1 Both political inclination and self-identity may also relate to the cognitive process of developing a place attachment. However, to highlight how differences in individual characteristics influence the development of place attachment, they were categorised here as inherent characteristics of individuals rather than as part of the process through which place attachment is developed.

3.2 The process dimension

Two variables were used to represent the process of developing place attachment: mobility (measured by the frequency of international travel) and global citizenship engagement. Proximity-maintaining behaviour has generally been considered the most important process in building place attachment (Hidalgo & Hernandez, 2001), and thus, we used mobility to capture such behaviour. Studies of the associations between mobility and place attachment have shown mixed results: Gustafson (2001) indicated that an excessively mobile self-perception was a threat to place attachment, whereas Bolotova et al. (2017) showed that individuals with a high level of travel mobility can maintain a strong sense of local attachment. To measure mobility in our survey, we asked the respondents to report their frequency of international travel on a 5-point scale (1 = never; 5 = always).

Responding to Scannell and Gifford (2010) suggestion that place attachment might not always be geographical and territorial in character, a second variable, global citizenship engagement, was introduced to represent the possible influence of non-geographical processes. Although both of the selected variables are related to all three aspects of the process dimension, global citizenship engagement might be relevant to this aspect as it could represent the development of an alternative to the frequently proposed dichotomy of local versus national identities in Hong Kong (Kit, 2014; Ma & Fung, 2007; Ortmann, 2017; Wong et al., 2021). Although this is a newly developed scale, the conceptual framework underlying it is borrowed from existing studies (Parmenter, 2011; Schattle, 2008), and several items are adapted from Martinsson and Lundqvist (2010). Global citizenship engagement was measured using six items that asked about the frequencies of six activities, such as “Keeping up with global affairs by reading international news” and “Being a member of a non-governmental organisation for a global cause.” A 5-point scale (1 = never, 5 = always) was used for each item and global citizenship engagement was the average of the scores for the six items.

3.3 The place dimension

In the place dimension of the proposed framework, this study sought to explore the influences of socio-political features of Hong Kong on place attachment. Two issues that are prominent in the current socio-political environment of Hong Kong—perceptions of inequality and perceptions of the law and legal system—were incorporated in the framework. Perceived inequalities of health and education have been shown to predict place attachment in other contexts (Calvo et al., 2017; Hautala et al., 2022). Hong Kong is notorious for having one of the highest levels of inequality of all advanced economies, which is associated with the extremely high cost of housing and might affect residents’ sense of belongingness to the city (Wong, 2020). The variable, inequality perceptions, was measured by averaging each respondent’s agreement with two statements on the severity of inequality in Hong Kong, namely “Differences in income in Hong Kong are too large” and “Disparity between the rich and the poor in Hong Kong has grown in the past 5 years.” A higher average score indicated a greater perceived inequality.

Public perceptions of the law and legal system have been closely connected with Hong Kong’s recent socio-political developments. For instance, after the social movements in 2019, the public experienced growing political turmoil that shook their confidence in the unique “One Country, Two Systems” constitutional framework for post-1997 Hong Kong designed to ensure judicial independence (Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2022a). As this variable has been frequently incorporated and tested in studies of other attachment-related socio-psychological variables, such as organisation commitment and civic engagement (Baek & Jung, 2015; Evers & Gesthuizen, 2011; Taniguchi & Marshall, 2014), it is likely to be pertinent to place attachment. We develop the scale based on a survey by Tyler and Jackson (2014) concerning legitimacy and legal authorities, with variations to selected questions for the Hong Kong context. The variable perceptions of the law and legal system was measured by averaging each respondent’s answers to five items, including “The law protects the interests of all citizens” and “The law is made through a fair procedure.” Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). A higher average score indicated a more positive perception of the legal system.

3.4 Data collection and data analysis

A random telephone survey of the local population aged 18 or older in Hong Kong was conducted with assistance from the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (PORI), an established local research centre.2 Some 1,295 citizens were approached and invited to take part in the survey; 801 responses were collected, of which 33 were excluded as incomplete, for a total sample size of 768. The effective response rate of the survey was 61.9%.

A multiple regression analysis was carried out to investigate the associations between the six variables in the three dimensions—political inclination and self-identity (person), mobility and global citizenship engagement (process), and inequality perceptions and perceptions of the law and legal system (place)—and the dependent variable of place attachment. In the regression models, we controlled for gender, age, and place of birth (a dummy on whether the respondent was born in Hong Kong). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for all the variables to confirm the reliability of the questionnaire items and variables, all of which are above the conventional threshold of 0.7 (with the exception of global citizenship scale at 0.621, which was still acceptable; see Taber, 2018).3 All statistical tests were conducted in SPSS (Version 26.0).4

4 RESULTS

The demographic information of the respondents is shown in Table 2. According to the Hong Kong census of 2021, males and females account for approximately 47% and 53% of the total population (Census and Statistics Department, 2021); the distribution in the current study was reasonably similar, with 42.7% male respondents and 57.3% female respondents. The age distribution of our sample was also similar to the official population figures (37.6% of our respondents aged above 60, as compared with 34% in the wider adult population; detailed distribution available in Appendix S1). Around two thirds of the respondents were born in Hong Kong, which is similar to the figure reported in the latest census. In general, the demographic distribution in the current study did not deviate greatly from that of the general population.

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 328 | 42.7 |

| Female | 440 | 57.3 |

| Place of birth | ||

| Hong Kong | 472 | 61.4 |

| Outside Hong Kong | 296 | 38.6 |

| Age | ||

| 18–19 | 25 | 3.3 |

| 20–29 | 117 | 15.2 |

| 30–39 | 105 | 13.7 |

| 40–49 | 109 | 13.0 |

| 50–59 | 119 | 14.2 |

| 60 or above | 289 | 37.6 |

| Decline to answer | 23 | 3.0 |

4.1 Place attachment and socio-political predictors

The distribution of responses and mean scores of the items measuring the six socio-political variables are presented in Table 1. The respondents reported a moderate level (that is, above the “neutral” level of three scores) of place attachment. They showed a particularly strong affective connection to Hong Kong by indicating that they mostly missed Hong Kong when they were away. Almost half of the respondents identified themselves as Hong Kongers, a third claimed a mixed identity of Chinese in Hong Kong or Hong Konger in China, and only around 15% identified solely as Chinese. Around 70% of the respondents identified with the pro-democracy camp, clearly outnumbering those identifying themselves as centralists or aligned with the pro-establishment camp. Around 20% of the respondents reported a high frequency of international travel and around half reported rarely or never having travelled outside of Hong Kong to an international destination. A fairly low level (that is, below the “neutral” level of three scores) of global citizenship engagement was reported in the survey, although the respondents reported a moderate level of engagement in global affairs in terms of keeping up with international news and engaging in environmental protection behaviour. On perceptions of the law and legal system, the respondents were most concerned about powerful people enjoying more protection under the law and using their power to manipulate other citizens. The respondents generally perceived a moderate-to-high level of inequality in Hong Kong, with inequality rated especially high in terms of gaps in wages and between the rich and poor.

4.2 Summary of multiple regression analysis on place attachment

To examine how different factors affect place attachment while controlling for omitted variables, a regression analysis was conducted. The results are shown in Table 3. A step-wise testing strategy was adopted, beginning with the person dimension in Model 1 and then adding the process dimension in Model 2, the place dimension in Model 3, and individual attributes in Model 4. Comparing the coefficients across the models, most estimates had similar levels of significance even with the inclusion of additional factors (with the partial exception of self-identity). These findings demonstrate that our framework can capture distinct dimensions of the underlying concept.

| Standardised coefficient (standard error) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Person | ||||

| Self-identity (Hong Konger) | −.210 (.097)*** | −.201 (.074)*** | −.154 (.072)** | −.144 (.076)* |

| Political inclination (pro-establishment) | .422 (.074)*** | .428 (.056)*** | .267 (.061)*** | .264 (.062)*** |

| Process | ||||

| Mobility | −.116 (.038)* | −.095 (.036)* | −.096 (.038)* | |

| Global citizenship engagement | .064 (.071) | .060 (.068) | .071 (.070) | |

| Place | ||||

| Inequality perceptions | −.044 (0.49) | −.048 (.050) | ||

| Perception of the law and legal system | .296 (.041)*** | .299 (.041)*** | ||

| Personal attributes | ||||

| Age | .033 (.074) | |||

| Gender | .055 (.050) | |||

| Place of birth | .025 (.093) | |||

| Adjusted R2 | .322 | .333 | .388 | .386 |

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < .001.

In Model 1, political inclination and self-identity were significantly (p < .001 for both variables) associated with place attachment. Pro-establishment citizens with stronger national identity recognition (that is, identifying as Chinese) tended to have higher place attachment, and the opposite was true for citizens with pro-democratic inclinations and a stronger local identity (that is, identifying as a Hong Konger). In Model 2, with the process dimension added, travel mobility was negatively associated with place attachment (p = .024), but there was no significant association between global citizenship engagement and place attachment. With the place dimension added in Model 3, perceptions of the law and legal system positively associated with place attachment (p < .001), while the coefficient of inequality perceptions was insignificant. Furthermore, the inclusion of these two variables in the model resulted in a decrease in the coefficient size and level of significance for self-identity, which might be attributable to an overlap between people’s confidence in the legal system and their local identity, as discussed below.

Finally, to test our framework against personal attributes, we included gender, age group, and place of birth as control variables in Model 4. None of the control variables were correlated with place attachment at conventional levels of significance and the estimates of all variables remained unchanged in terms of coefficient size and significance level (with the partial exception of self-identity, which became less significant). The most interesting result in Model 4 was the lack of a correlation between place attachment and place of birth. Whether respondents were born in Hong Kong was irrelevant to their place attachment, which was associated only with their actions and beliefs as captured in the PPP-based framework. Including these control variables also added little explanatory power to the model (adjusted R-squared 0.388 in Model 3 and 0.386 in Model 4). These results suggest that the factors in our proposed PPP-based framework are powerful determinants of place attachment, especially compared with personal background and attributes.

5 DISCUSSION

By developing and testing an analytical framework of place attachment based on the PPP framework, this study demonstrates the relevance of socio-political factors in shaping and determining place attachment. It also highlights the complexity of place attachment, with significant results identified in all three dimensions of the PPP framework.

In the person dimension, both self-identity and political inclination were significantly correlated with place attachment. From the perspective of social identity theory, a social identity can be formed by finding similarities with other “in-group” members and distinctiveness from “out-groups.” Having such feelings of similarity and distinctiveness can help to develop place attachment but being an out-group member can lead to a lower sense of place attachment (Brewer, 1991; Scannell & Gifford, 2010). This perspective can explain our results for the role of self-identity and political inclination. That the respondents who identified as “Hong Kongers” felt less attached to Hong Kong might imply that self-identified Hong Kongers perceive themselves as a marginalised “out-group” in Hong Kong society. Although they were the largest group in the sample, they may perceive themselves as outcasts given the current social and political developments. For example, under the National Security Law, those who do not share the “correct” understanding of rule of law—the “political outcast”—will need to adjust their behaviour (if not their thinking) to conform. Those, on the other hand, who fully identify with the motherland and endorse the associated laws and policies—the “politically correct”—naturally become “desirable” members of society. That may help explain why those respondents who claimed a “Chinese” identity showed a higher level of attachment, which might indicate that they perceive themselves as part of the mainstream social in-group. Similarly, the tendency for self-proclaimed pro-democratic citizens to have a lower level of place attachment might imply a perceived incompatibility with the current political environment of Hong Kong that could lead to a decline in opportunities to climb the social ladder and unpredictable risks associated with expressing their political views. The arrests of over 50 pro-democracy activists for allegedly violating the National Security Law by organising or taking part in unofficial primary elections in 2020 is a case in point (BBC, 2021). In contrast, the higher degree of place attachment among citizens with pro-establishment inclinations might indicate their satisfaction with the current political climate, which reflects their political views and values and enables them to feel a sense of belonging and attachment to Hong Kong.

For the process dimension of place attachment, mobility was the only variable that showed a significant relationship with place attachment. Mobility in terms of frequency of international travel was negatively associated with place attachment, which is generally consistent with the findings of traditional studies of mobility. In the literature, mobility and place attachment are generally considered contradictory and even mutually exclusive (Gustafson, 2001), with a strong sense of attachment often deemed as a sign of insularity that reduces mobility and a high level of mobility is often associated with a sense of uprootedness and a loss of attachment (Barcus & Brunn, 2010; Relph, 1976). These findings indicate that the proximity-maintaining processes or behaviours that connect people with places are still the key to place attachment even in this era in which social connections are no longer limited by time and space. They also imply that physical connections with a place are just as important to attachment as social connections. In the case of Hong Kong, such findings might be a worrying sign for the city’s future. Government statistics show that the outward movement of the local population has been growing in recent years (Census and Statistics Department, n.d.). The Hong Kong government claimed that outward movements of citizens could be related to various factors, such as work and study and that the figures do not necessarily indicate that citizens are permanently leaving Hong Kong or intending to emigrate (South China Morning Post, 2021). Nonetheless, our results suggest that merely being away from Hong Kong frequently or for long periods of time can diminish people’s levels of place attachment and perhaps therefore reduce their propensity to return. Unexpectedly, the respondents’ levels of global citizenship engagement were not associated with their place attachment, suggesting that their sense of identity at the local and national levels might not contradict their identity at the global level.

Last but not least, the place dimension of place attachment in this study focuses on the socio-political features of contemporary Hong Kong. Most crucially, this study highlights the association between place attachment and perceptions of the law and legal system in light of the drastic recent socio-political changes in Hong Kong. Our results indicate that positive perceptions of the law and legal system were positively associated with place attachment, which means that those who reported negative perceptions tended to feel less attached to Hong Kong. Indeed, perceptions of and confidence in public institutions were found to be a determinant of place attachment among Norwegian citizens (Lynnebakke & Aasland, 2022). According to a rolling survey of Hong Kong citizens conducted for over 30 years by PORI Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (2022b), trust in the government was at its lowest level in 2020, and over 50% of citizens still indicated that they did not trust the government in 2022. Until 2019, this figure had never reached 50%. Besides, judicial independence has long been promised under the Hong Kong Basic Law. Yet the enactment of the National Security Law in July 2020 and its subsequent implementations (the appointment of a “select” panel of judges to handle related cases) showed a high degree of political intervention in the judiciary by the Hong Kong SAR and central governments. Therefore, negative perceptions of the legal institutions at this critical juncture might imply and reflect a similar level of institutional mistrust in the local government, leading to a downward trend in place attachment among Hong Kong people. That some Hong Kong citizens harbour a sense of mistrust in the government has potentially far-reaching implications. One of them is their sense of cooperation with authorities. When citizens do not trust the government, they may not be as willing to assist (or be part of) the law enforcement agencies in crime investigation and even to serve as jury members. According to Tyler (2001), that may also affect people’s willingness to obey the law. The recent relaxation of recruitment criteria of the Hong Kong Police, including the removal of height and weight restrictions and adjustments of the language proficiency requirements, maybe a case in point (The Guardian, 2023). Besides suggesting that the police is facing challenges in recruiting new blood, it can also be part of a broader brain-drain problem.

On the other hand, we stress that while inequality perceptions were not significantly correlated with place attachment, it does not mean this factor is not practically significant. In fact, inequalities of income and wealth are longstanding issues in Hong Kong and arguably worsening (Piketty & Yang, 2022; Wong, 2020) and that a strong majority of our respondents find it a serious matter (over 50% strongly agree with another 30% agree). Our results merely indicate that place attachment is perhaps more of a socio-political concept (affected by identity, views of the legal system, etc.) than an economic one.

As suggested by Scannell and Gifford (2010), the PPP framework allows for the identification of the different effects of each dimension of place attachment and of the individual effects of various factors within the dimensions. From a theoretical perspective, this study found that the person and place dimensions, in the context of Hong Kong’s current socio-political situation and the personal characteristics of its people, exerted greater influences on place attachment than the process dimension. How Hong Kong citizens perceive and position themselves amid the changing socio-political trajectory of Hong Kong could therefore be the key to determining their level of place attachment. By comparing the three dimensions within the PPP framework and highlighting the notable differences between them, this study also showcases the applicability of the PPP framework in this context. From a practical standpoint, the major findings of this study highlight how the changing political climate could pose challenges on the building of place attachment of Hong Kong people, as well as possible difficulties on governance given the apparently growing trends of emigration and mistrust of government and legal institutions.

A limitation of this study is that we have only been able to identify the correlation, but not causal effect, of the variables involved. Arguably, instead of seeing place attachment as an outcome, we can treat it as a factor driving the patterns identified (place attachment leading to mobility actions). It is also likely that the whole process is endogenous. While this possibility cannot be ruled out empirically in this study, our proposed theoretical framework makes our preferred interpretation a more likely scenario. Another limitation is that although our findings reveal the extent of the influence of socio-political changes on people’s place attachment, only a limited number of variables were adopted in this study to measure each of the three dimensions in the proposed framework. To further investigate the relationships between socio-political factors and place attachment, future studies could include additional factors under the three dimensions when adopting a similar model based on the PPP framework. Arguably, the weaker results associated with the process dimension might also be put down to our choice of measures, rather than the lack of a real effect. In this regard, their involvement in the society or the political system might be interesting variables under this dimension. Attention can also be paid to the operationalization and applicability of the global citizenship scale in our study, whose reliability can be further improved.

6 CONCLUSION

This study incorporates socio-political factors into a proposed framework for measuring place attachment based on the PPP model. Using Hong Kong as a case study, it demonstrates that socio-political factors can significantly shape people’s place attachment through the person, process, and place dimensions of the PPP model. The findings for the person dimension largely reflect the current socio-political situation of Hong Kong, where citizens who believe they are part of the political mainstream showed a higher level of place attachment. The findings for the process dimension highlight the importance of proximity-maintaining behaviours and the potential consequences of massive outward population movements. The strong associations found between place attachment and perceptions of the law and legal system also suggest the relevance of the place dimension with people’s sense of place attachment. To conclude, applying the multidimensional PPP framework in the case of Hong Kong, this study found that the person and place dimensions had relatively greater influences on people’s place attachment than the process dimension. Despite the unique features of Hong Kong, the findings of this study have both local and global implications.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Education University of Hong Kong (Ref.: 2020-2021-0225) prior to the commencement of the project.

ENDNOTES

- 1 The scales for political inclination and self-identity were both developed with reference to the measurements of their respective variables in a poll that has been conducted by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (PORI) for over 30 years.

- 2 The telephone survey was carried out in May and June of 2021 with a Web-based Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (Web CATI) system. The method is considered as the standard random sampling method (for telephone surveys) in Hong Kong. Equal numbers of landline and mobile numbers were included in the sampling. The detailed data collection method is provided in Appendix S1.

- 3 While a high Cronbach alpha is generally a good sign, some argue that a score above 0.9 is indicative of repetitive items, which might be the case for our perception of the law and legal system variable. We have tested with alternative operationalisations (removing one item), which would bring the score below 0.9 and find that the results are unchanged.

- 4 Multicollinearity is not a concern here according to tolerance and VIF statistics (available in Appendix S1).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.