Assessing the value of a pelvic drain for urinary leak after robotic radical prostatectomy

Hilly Perlman made an equal contribution as the first author.

Yuval Bar-Yosef made an equal contribution as the last author.

This work was performed in partial fulfilment of the M.D. thesis requirements of the Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University.

Abstract

Aim

The value of post-operative pelvic drain placement after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) for the purpose of diagnosing post-operative complications is undetermined. The aim of this study was to assess the yield of pelvic drain outputs in predicting post-operative early-onset urinary leaks from a vesicourethral anastomosis.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 204 consecutive patients who underwent RARP in our institution between 2018 and 2022. The daily outputs of the drain and the urinary catheter were measured, and patients with early-onset anastomotic urinary leak were compared with those who were free of any leak. The association between post-operative drain output and the presence of urinary leak was investigated by regression analyses.

Results

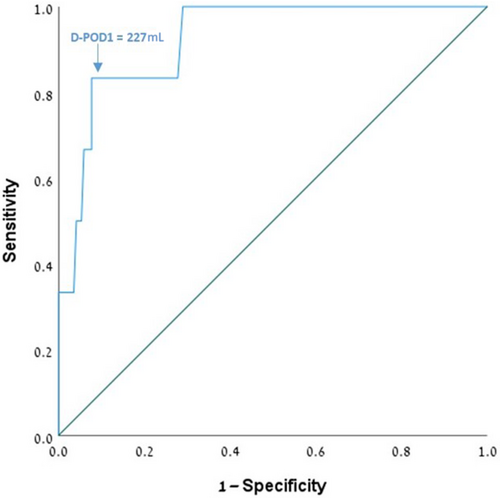

Post-operative early-onset leak was present in six patients (3.4%) whose baseline characteristics were not different from those of patients with no leak. The median pelvic drain output on post-operative day 1 (D-POD1) was 80 mL (interquartile range [IQR] 51–150 mL) and 122 mL (IQR 62–200 mL) on D-POD2. The median D-POD1 of patients with a leak was significantly higher than those without one (250 mL vs 80 mL, respectively; P < .001). The threshold to predict an anastomotic urinary leak was 227 mL on D-POD1 (area under the curve 0.88; P < .001), and an association between D-POD1 >227 mL and the presence of urinary leak (odds ratio 35; P < .001) was found.

Conclusions

Pelvic drain output on POD1 can predict early-onset urinary leak. Given the relatively low rate of this complication via a robotic approach, however, we consider that, unless otherwise indicated, the routine placement of a pelvic drain may be safely avoided.

Abbreviations

-

- D/U ratio

-

- daily ratio of drain to urine outputs

-

- D-POD

-

- daily output of pelvic drain during the post-operative day

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- PCa

-

- prostate cancer

-

- POD

-

- post-operative day

-

- PSA

-

- prostate-specific antigen

-

- RARP

-

- robot-assisted radical prostatectomy

1 INTRODUCTION

Radical prostatectomy is currently the gold-standard treatment for clinically localised prostate cancer (PCa).1 From the time of its introduction, robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) has changed perspectives regarding surgical options and gained popularity over open and purely laparoscopic prostatectomy.2 RARP affords numerous benefits, such as reduced blood loss and fewer days of hospitalisation3, 4 while maintaining equivalent oncological and functional outcomes.4, 5 Despite the rapid diffusion of RARP as the standard of care internationally, the need for routine insertion of a pelvic drain remains equivocal.6 The rationale for the insertion of a drain following RARP is multifaceted, with many indications continuing to be anchored to past paradigms not necessarily relevant to the ‘new era’ of robotic surgery.

A urinary leak from the urethrovesical anastomosis is one of the most significant short-term complications of RARP. The aim of our study was to assess the yield of pelvic drain outputs in predicting early-onset leak from a vesicourethral anastomosis and determine the necessity of routinely placing a pelvic drain following RARP.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

After obtaining institutional ethics committee approval and waiver of informed consent, we performed a retrospective analysis of all patients who underwent RARP at our centre between 2018 and 2022. We included patients with a clinically and histologically confirmed localised or locally advanced PCa (clinical stage T1-4; N0-1; M0 according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] 8th edition) treated by RARP with pelvic drain placement at the end of the surgery. We excluded all patients with a history of pelvic radiotherapy and/or previous urethral surgery and/or known urethral stricture.

2.2 Surgical procedure and post-operative management

All procedures were performed by two expert surgeons (O.Y. and A.B.) who had already reached the plateau of their learning curve.7, 8 The decision to perform extended pelvic lymph node dissection and/or a nerve-sparing technique during RARP depended on the baseline characteristics of the patients and tumour characteristics in accordance with the American Urological Association (AUA)/American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO)/Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) recommendations.9 At the end of each procedure, we routinely placed a Jackson–Pratt pelvic drain forming a ‘U’ shape anterior to the bladder and the anastomosis. Post-operative management included clinical and laboratory follow-ups, input and output measurements, enhanced recovery protocol, and routine discharge on post-operative day (POD)-2 with a urinary catheter in place after removal of the drain. The urinary catheter was routinely removed at the outpatient clinic on POD10.

2.3 Data collection

Data on the patients’ clinical (age, prostate-specific antigen [PSA] level, and staging), surgical (length of surgery and posterior reconstruction), and pathological (pTNM) characteristics were collected from the medical records of our institution. Clinical staging was performed according to PSA values, and findings of the rectal examination, magnetic resonance imaging, nuclear imaging, bone scans, and computed tomography. All pathological specimens were interpreted by a dedicated genitourinary pathologist. The post-operative variables were daily outputs of the pelvic drains during POD1 (D-POD1) and POD2 (D-POD2), and 24-h urine outputs and their daily ratios (ie, the daily ratio of drain to urine outputs [D/U ratio]).

2.4 Endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study was the value of drain placement in the identification of early-onset urethrovesical anastomotic leaks during post-operative hospitalisation. All clinically suspected urinary leaks were confirmed by computed tomography cystography. The cohort was stratified according to the identification of post-operative urinary leaks.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics included frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuously coded variables. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed by means of the Fisher exact and Mann–Whitney U tests. Univariate logistic regression was performed to calculate the association between drain outputs and study endpoints, and the number of patients needed to drain for urinary leak identification was calculated. All analyses were two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as P < .05. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 29 (IBM, New York, NY).

3 RESULTS

The cohort included 204 patients with a median age of 66 years (IQR 62–70 years) and a median PSA level of 7.3 ng/dL (IQR 5.5–11 ng/dL). Their baseline clinical, surgical, and pathological characteristics stratified by urinary leak status are presented in Table 1. The preoperative, operative, and pathological characteristics were not different between the urinary leak group and the no-leak group (Table 1). The early-onset anastomotic urinary leak rate during hospitalisation was 3.4% (n = 7 patients).

| Variable | Overall (n = 204) | No urinary leak (n = 197) | Urinary leak (n = 7) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | ||||

| Age (years) | 66 (62–70) | 66 (62–71) | 66 (62–70) | .99 |

| PSA (ng/dL) | 7.3 (5.5–11) | 7.3 (5.5–11) | 6.5 (4.2–12) | .96 |

| cT | .87 | |||

| 1a-b | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 1c | 126 (62) | 120 (61) | 6 (86) | |

| 2 | 65 (32) | 64 (32) | 1 (14) | |

| 3 | 9 (4) | 9 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Operative | ||||

| LOS, min | 176 (145–241) | 177 (144–243) | 171 (158–230) | .99 |

| Posterior reconstruction | 150 (74) | 143 (73) | 7 (100) | .35 |

| Pathological | ||||

| PSM | 46 (22) | 45 (23) | 1 (14) | .93 |

| ECE | 80 (39) | 76 (39) | 4 (57) | .43 |

| SVI | 33 (16) | 31 (16) | 2 (29) | .32 |

| LNI | 11 (5) | 10 (5) | 1 (14) | .33 |

| Weight, g | 51 (42–64) | 50 (42–63) | 68 (37–73) | .33 |

- Note: Continuous variables are reported as median (IQR) and categorical variables as n (%).

- Abbreviations: ECE, extracapsular extension; IQR, interquartile range; LNI, lymph node involvement; LOS, length of surgery; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PSM, positive surgical margin; SVI, seminal vesicle invasion.

The median D-POD1 was significantly higher (P < .001) among patients with a urinary leak (median 250 mL, IQR 130–625 mL) compared with others (median 80 mL, IQR 50–140 mL). The patients who sustained early-onset urinary leaks consistently presented with a higher D/U ratio on POD1 (median 0.22 vs 0.04, respectively; P < .001; Table 2). These differences were no longer significant on POD2. The receiver operating characteristics curve (Figure 1) was used to evaluate the model's predictive performance for early-onset vesicourethral anastomotic leakage. The receiver operating characteristics curve determined that D-POD1 = 227 mL was the threshold for predicting an anastomotic leak (area under the curve 0.88, 95% confidence interval 0.78–0.99; P < .001). A univariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated a significant association between D-POD1 >227 mL and the presence of a urinary leak (odds ratio 35, 95% confidence interval 6–200; P < .001). The minimum number needed to predict a single patient with a urinary leak was 29.

| Variable | Overall (n = 204) | No urinary leak (n = 197) | Urinary leak (n = 7) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-POD1 (mL) | 80 (51–150) | 80 (50–140) | 250 (130–625) | <0.001 |

| D/U ratio POD1 | 0.04 (0.02–0.08) | 0.04 (0.02–0.07) | 0.22 (0.09–0.26) | <0.001 |

| (n = 79) | (n = 73) | (n = 6) | ||

| D-POD2 (mL) | 122 (62–200) | 120 (60–200) | 210 (112–1770) | 0.11 |

| D/U ratio POD2 | 0.05 (0.02–0.09) | 0.04 (0.02–0.09) | 0.09 (0.03–1) | 0.17 |

- Note: Continuous variables are reported as median (IQR) and categorical variables as n (%). Bold indicates significant value.

- Abbreviations: D-POD, drain output on post-operative day; D/U, drain-to-urine ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

4 DISCUSSION

Robotic technology bestows the possibility of preserving key anatomic structures and minimising the perioperative complications during radical prostatectomy, thereby vastly changing the perception of prostate surgery. RARP has now become the new ‘gold standard’ approach for the surgical treatment of localised PCa. The vesicourethral anastomosis made possible by the robotic approach is more accurate and tighter compared with other approaches, resulting in fewer occurrences of anastomotic urine leak and subsequent urinoma.10 Previous studies on this new approach had focused mainly on the major issues of oncological and functional outcomes. We now consider that enhanced imaging capabilities, better handling of tissues, and the finer movements afforded by the robotic approach may have decreased the level of concerns from a leak. This possibility was supported by more recent studies that estimated the incidence of anastomotic leak during RARP to range between 0.1% and 6%.11, 12

Danuser et al13 questioned the need for pelvic drain placement in RARP and suggested that it may be significantly less than in open prostatectomy techniques. Even earlier, Sharma et al14 presented a concept of omitting the drain altogether. There are, however, numerous considerations underlying the rationale of placing a pelvic drain during this type of surgery, especially its role as an early indicator of anastomotic leak, bleeding, and lymphatic leak. A recent randomised controlled trial showed no significant benefit in placing a drain in the pelvic cavity after RARP.6 Moreover, drain placement has been associated with surgical site infections,15 pain at the drain site,16 and bleeding.17 Niesel et al16 found that one-third of patients had post-operative pain associated with either the incision or drain site after radical prostatectomy and retroperitoneal drainage after gynaecologic abdominal surgery was found to increase post-operative hospital stay with higher complication rates (P < .001). These may interfere with the ‘fast-track’ pathway following surgery by delaying hospital discharge and consequently increasing hospital costs.

Our study focused on the potential yield of a pelvic drain in predicting post-operative early-onset urinary leak from the vesicourethral anastomosis, and the results confirmed that the drain output represents a valid prediction tool for urinary leak. Interestingly, the significance between the drain outputs of patients who sustained urinary leaks and those who did not vanished on POD2. These findings suggest that drain output is a valid predictor of urinary leak, but that its effectiveness is less evident after the first post-operative day. This could be related to the increase in lymph secretion caused by the irritative effect of drainage in the pelvic cavity. In addition, with the early-onset anastomotic urinary leak rate identified by cystography to be as low as 3.6%, the ‘number needed to drain’ to be able to predict a single patient with urinary leak on cystography is 29 patients. Considering these findings alongside the relatively low rate of urinary leak complications associated with a robotic approach, we conclude that, unless specifically indicated otherwise, it may be safe to forgo routine placement of a pelvic drain.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it is a single-institution retrospective cohort study with a sample size that may limit the significance of the findings. Second, the low number of urinary leaks precluded the performance of a multivariate analysis. Despite these limitations, we believe that this study contributes clinically relevant findings to the ongoing uncertainty of the value of drain placement following RARP.

In conclusion, the placement of a pelvic drain can serve as a useful tool to predict early-onset anastomotic urinary leaks in the post-operative management of patients after RARP. The findings of our analysis, however, lead us to consider that its routine use in RARP may be avoided and saved to selected patients, based on the relatively low rate of this complication. Further prospective randomised trials are needed to establish our results.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design—Eugenio Bologna, Hilly Perlman and Ziv Savin. Acquisition of data—Eugenio Bologna, Hilly Perlman, Idan Zeeman, Tomer Bashi, and Karin Lifshitz. Analysis and interpretation—Eugenio Bologna, Hilly Perlman Snir Dekalo, Roy Mano, and Ziv Savin. Drafting of the manuscript—Eugenio Bologna, Hilly Perlman and Ziv Savin. Critical revision of the manuscript—Avi Beri, Ofer Yossepowitch, Snir Dekalo, and Roy Mano, Yuval Bar-Yosef. Statistical analysis—Ziv Savin and Roy Mano. Supervision—Ziv Savin.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.