Emergency examination authorities in Queensland, Australia

Abstract

Objective

In Queensland, where a person experiences a major disturbance in their mental capacity, and is at risk of serious harm to self and others, an emergency examination authority (EEA) authorises Queensland Police Service (QPS) and Queensland Ambulance Service (QAS) to detain and transport the person to an ED. In the ED, further detention for up to 12 h is authorised to allow the examination to be completed. Little published information describes these critical patient encounters.

Methods

Queensland's Public Health Act (2005), amended in 2017, mandates the use of the approved EEA form. Data were extracted from a convenience sample of 942 EEAs including: (i) patient age, sex, address; (ii) free text descriptions by QPS and QAS officers of the person's behaviour and any serious risk of harm requiring urgent care; (iii) time examination period commenced; and (iv) outcome upon examination.

Results

Of 942 EEA forms, 640 (68%) were retrieved at three ‘larger central’ hospitals and 302 (32%) at two ‘smaller regional’ hospitals in non-metropolitan Queensland. QPS initiated 342 (36%) and QAS 600 (64%) EEAs for 486 (52%) males, 453 (48%) females and two intersexes (<1%), aged from 9 to 85 years (median 29 years, 17% aged <18 years). EEAs commonly occurred on weekends (32%) and between 2300 and midnight (8%), characterised by ‘drug and/or alcohol issues’ (53%), ‘self-harm’ (40%), ‘patient aggression’ (25%) and multiple prior EEAs (23%). Although information was incomplete, most patients (78%, n = 419/534) required no inpatient admission.

Conclusions

EEAs furnish unique records for evaluating the impacts of Queensland's novel legislative reforms.

Key findings

- Queensland is the only Australian jurisdiction where a person is detained for an examination in an ED under public health law, specifically, an emergency examination authority.

- Although information is incomplete, most emergency examination authority patients are discharged following examination.

- Yet many have experienced self-harm and more than half have serious substance abuse problems.

Introduction

In Queensland, an amended Public Health Act 2005 (‘PHA’) and a new Mental Health Act 2016 (‘MHA 2016’) were implemented in tandem from 5 March 2017.1-3 Section 157B of the PHA permits Queensland Police Service (QPS) and Queensland Ambulance Service (QAS) officers to detain and transport a person to a ‘treatment or care place’, usually a hospital ED, if ‘the person appears to require urgent examination or treatment and care’ and where the officer believes the person to be at ‘immediate risk of serious harm’, e.g. threatening to commit suicide, because of an apparent ‘major disturbance in mental capacity’.3 The ‘major disturbance in mental capacity’ may be because of ‘illness, disability, injury, intoxication or another reason’.3, 4 In the broad context where mental health laws in Australia are evolving in response to international human rights obligations, mental health legislation authorises similar intervention in most Australian jurisdictions.5

In a recent perspective in this journal, we suggested that a diminution of publicly-available information about emergency examination authorities (EEAs) under Queensland's new legislation has made it more difficult to analyse patterns, trends and regional variations in mental healthcare needs and more difficult to formulate suitable responses.6 This paper examines the scope and significance of information contained in the ‘approved form’ required for an EEA by the PHA.7

- Section 157F (2) permits a ‘doctor or authorised mental health practitioner’ to examine a person subject to an EEA specifically ‘to decide whether to make a recommendation for assessment for the person under the Mental Health Act 2016’.3

- Section 157F (1) permits a ‘doctor or health practitioner’ to examine a person ‘to decide the person's treatment and care needs’ more generally.3

Although it is possible to retrieve individual-level data for persons subject to EEAs from some administrative collections, under the 2017 reforms, local arrangements for recording EEAs in patient records are to be followed in each Queensland Health hospital.4 Additionally, since neither QPS nor QAS maintains an archive of EEA forms, any comprehensive evaluation of the impacts of Queensland's new approach to mental health legislation is particularly challenging and none has been conducted. To provide a basis for such an evaluation we worked collaboratively in five hospital EDs in one large non-metropolitan Queensland region. We describe the procedures needed to retrieve a sample of EEA forms and to extract relevant information. We describe the population of patients for whom emergency examination was required, the reasons for, and the circumstances surrounding, an emergency examination and the outcome for the patient. Issues relevant for improving patient care and for formulating suitable mental healthcare responses are highlighted for further consideration.

Methods

Setting

Around 720 000 people live in the study region where almost one in five are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.6 Larger hospitals in major centres in the ‘outer regional’ locational category8 service the bulk of the study region's population; 664 735 (92.4%). Smaller hospitals with inpatient capacity situated in ‘very remote’8 parts of the region service a population of 54 810 (7.6%).

Sampling

To represent the diversity of hospitals and demographic settings across the region, a convenience sample of two smaller hospitals in ‘very remote’ locations and three larger hospitals in ‘outer regional’ locations was selected.

Random sampling of EEAs at each hospital was not possible. A convenience sample of 942 EEA forms, made out between April 2017 and December 2020 (the ‘observation period’), was compiled. Annual reports of the Chief Psychiatrist for 2017–2018 to the present declared 2529 EEAs in total for the study region.9-12 However, perhaps four times this number were made out by QPS and QAS officers, according to our previously-published estimates.6 It is therefore possible that the sample represents perhaps 10% of all EEAs made out during the observation period.

Sampling procedures

With some hospitals using paper-based systems13 and no single electronic archive available, individual forms were retrieved manually from the paper and electronic records available at each hospital. At each hospital ED, patients with ‘arrival transport mode’ of either ‘police’ or ‘ambulance’ from 5 March 2017,14 were flagged by patient records management staff as candidates for potential inclusion. Patient files thus flagged were then retrieved and hand-searched by the researchers for any EEA forms contained therein. Identifying information was masked before capturing an image of the form for later transcription and coding. Quotas were used to represent, as far as practicable, broad age and gender groups in those requiring emergency mental healthcare in Queensland as a whole and to balance numbers of QPS- and QAS-declared EEAs across hospital catchments.

The EEA form and derived variables

- Gender (male, female, intersex/indeterminate);

- Age group at the date the EEA was declared (aged <18 years, 18–24, 25–49, 50 years and over);

- Whether QPS- or QAS-declared;

- Possible multiple EEAs within the period (categorised as ‘1 only’ or ‘≥2’);

- Self-harm observed and described by QPS or QAS (coded ‘yes’ or ‘no record’);

- Person aggressive towards others including QPS or QAS (coded ‘yes’ or ‘no record’);

- Drugs and/or alcohol issues evident to QPS or QAS (coded ‘yes’ or ‘no record’);

- Outcome of examination of the person recorded as ‘admitted as inpatient and/or recommendation for assessment made under the MHA 2016’ or ‘examination, treatment or care provided and person discharged, EEA ended’;

- Time (24 h) the ‘examination period’ commenced; and

- Day of the week.

Analysis

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the sample in terms of demographic and locational variables.

| Section on EEA form from which information was derived | Total (n = 942), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cover page | |

| Smaller regional | 302 (32) |

| Larger central | 640 (68) |

| Section 1 ‘Person's details’ | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 453 (48) |

| Male | 486 (52) |

| Intersex | 2 (<1) |

| Age group at time of EEA | |

| <18 years | 159 (17) |

| 18–24 years | 215 (23) |

| 25–49 years | 450 (48) |

| ≥50 years | 118 (13) |

| Section 4 ‘Declaration’ | |

| QPS-declared | 342 (36) |

| QAS-declared | 600 (64) |

Table 2 compares EEAs at ‘smaller regional hospitals’ (the reference category) with EEAs at the ‘larger central hospitals’. Comparisons were made in terms of possible multiple EEAs during the observation period and, where data permitted, in terms of the criteria for being transported, i.e. any recorded observations by QPS or QAS of self-harm, patient aggression towards others and drugs and/or alcohol involvement. Comparisons were also made between ‘admitted and/or recommendation for assessment under MHA 2016’ and the category ‘examination, treatment, care, discharged, EEA ended’ (Table 2).

| Section on EEA form from which information was derived | Hospital type, n (%) | RRR | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smaller regional (n = 302)† | Larger central (n = 640) | Total (n = 942) | ||||

| Possible multiple EEAs within the period | ||||||

| 1 only† | 216 (72) | 511 (80) | 727 (77) | 1.0 | ||

| 2 or more | 86 (28) | 129 (20) | 215 (23) | 0.6 | 0.3–1.2 | 0.160 |

| Section 2 ‘Criteria for being transported’ | ||||||

| Self-harm observed and described by QPS or QAS | ||||||

| Not recorded† | 191 (63) | 280 (57) | 471 (60) | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 110 (37) | 209 (43) | 319 (40) | 1.3 | 0.5–3.6 | 0.620 |

| Person aggressive towards others including QPS or QAS | ||||||

| Not recorded† | 211 (74) | 475 (75) | 686 (75) | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 76 (26) | 156 (25) | 232 (25) | 0.9 | 0.6–1.5 | 0.698 |

| Drugs and/or alcohol issues evident to QPS or QAS | ||||||

| Not recorded† | 133 (44) | 272 (49) | 405 (47) | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 166 (56) | 285 (51) | 451 (53) | 0.8 | 0.4–1.6 | 0.601 |

| Section 9 ‘Examination of person’ | ||||||

| Admitted and/or recommendation for assessment under MHA 2016† | 33 (41) | 82 (18) | 115 (22) | 1.0 | ||

| Examination, treatment, care, discharged, EEA ended | 47 (59) | 372 (82) | 419 (78) | 3.2 | 1.6–6.2 | 0.001 |

- † Reference category.

Multinomial logistic regression (Stata 17; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) was used to calculate relative risk ratios (RRRs; and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) comparing the probability (risk) of each outcome by type of hospital. Clustered robust standard errors were estimated (vce option in Stata) to accommodate clustering effects of sampling within five hospital catchments.15

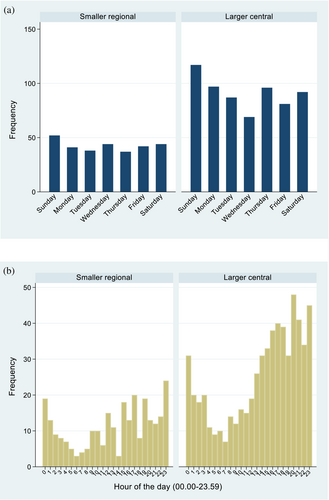

Time (24 h) and weekday of the EEA presentation by type of hospital were analysed graphically (Fig. 1).

Multicentre ethics approval was obtained from the Townsville Hospital and Health Services Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Reference number: LNR/2018/QTHS/46061) and James Cook University (HREC Reference number: H7672).

Results

Of the 942 EEA forms in the sample, 640 (68%) were retrieved at the region's three ‘larger central’ hospitals and 302 (32%) at two ‘smaller regional’ hospitals (Table 1). QPS initiated 342 (36%) and QAS 600 (64%) EEAs for 486 (52%) males, 453 (48%) females and two intersexes (<1%) and patients ranged in age from 9 to 85 years at the time of presentation (median 29 years, 17% aged <18 years) (Table 1). The youngest person subject to an EEA was 9 years old at the time; 17% were aged <18 years (Table 1), and the oldest was 85 years (median 28.8 years). One young person was subject to an EEA on 10 occasions between ages 16 and 17 and on a further three occasions when aged 18, with actual self-harm evident on nine of these occasions (data not shown).

- The sample of EEAs contained proportionally fewer QAS-declared EEAs (64%) than across Queensland (87%) (|z| = 1.47, P = 0.146, two-sample test of proportions), reflecting our efforts to balance numbers of QPS- and QAS-declared EEAs in sampling;

- Gender representation (52% males, 48% females) was identical to Queensland's and the proportion aged <45 (80%) was also very similar (78%) (|z| = 1.47, P = 0.146, two-sample test of proportions).

It is possible that almost one-quarter (23%) of the sample were subject to two or more EEAs during the observation period, with proportions not significantly different between hospital types (RRR 0.6, 95% CI 0.3, 1.2, P = 0.160) (Table 2).

- In 40% of EEAs self-harm was evident;

- In 25% the person was aggressive towards others; and

- In 53% drugs and/or alcohol issues were evident (Table 2).

These proportions were not significantly different between hospital types (Table 2). However, Table 2 indicates that although in just 57% (n = 534/942) of EEAs section 9 had been completed with an outcome of the examination of the person recorded, among the 534 with recorded outcomes, 22% were in the category ‘admitted and/or recommendation for assessment made under MHA 2016’, while the great majority (78%) were in the ‘examination, treatment, care, discharge, EEA ended’ category. This result occurred more often, on 82% of occasions, at the ‘larger central’ hospitals in contrast with 59% of occasions for ‘smaller regional’ hospitals (RRR 3.2, 95% CI 1.6, 6.2, P = 0.001) (Table 2).

Figure 1 indicates that both hospital types experienced similar weekly (Fig. 1a) and similar daily (Fig. 1b) cycles in terms of when a person is taken to an ED under an EEA. Also found across Queensland hospitals,16 for the observation period, weekends (and Monday's aftermath) and evening to early morning hours were busiest at both hospital types.

Discussion

The approved EEA form required by the PHA uniquely records a critical transaction between a person who appears to be experiencing an acute behavioural disturbance in the Queensland community on the one hand, and the key emergency services charged with their care on the other; QPS, QAS and hospital EDs.

Despite sampling limitations making it difficult to generalise from the results, discharge following examination in the present study (78%) is comparable to rates found in the few available single-site chart audit studies.17, 18 However, the broad age and gender characteristics of the sample, similar to those seen in emergency mental healthcare presentations across Queensland, make generalisation possible.

The unique description of information from EEA forms our study provides alerts us to at least the following issues for further examination.

The large number (17% in the cohort) aged under 18 years who are subject to an EEA is concerning.19-21 It indicates that QAS and QPS have few appropriate child and youth mental health and other support service alternatives to the use of involuntary detention and transport to a hospital ED.22 Clinical experience suggests that ever-younger persons are presenting more frequently to EDs in the study region with acute severe behavioural disturbance. Over-representation of young people in involuntary care in childhood, with previous involuntary admission a key driver,20, 23, 24 might establish potentially longer-term trajectories and repeating cycles in the need for emergency mental healthcare.20 However, the PHA is silent regarding least-restrictive options for QPS, QAS and EDs where children meet criteria for an EEA in the first instance.

High rates of aggression and drug and alcohol involvement in the sample would appear to vindicate the Queensland's legislators' express priority concerns for the efficient use of health system resources and concern for safety in public sector health service facilities.1, 24, 25 Legislators framed the new legislation in the stated belief that the majority of people subject to an EEA ‘are instead suffering from drug or alcohol abuse, with no underlying mental illness that warrants action’.1, 24, 25 Our study suggests that this reasoning became operationalised with 78% of persons subject to an EEA discharged following examination and treatment and just 22% admitted or recommended for assessment under the MHA 2016 (Table 2). However, we have no information to explain why patients are more frequently discharged at the ‘larger central’ hospitals (82%), rather than receiving more specialised mental health treatment, compared with the ‘smaller regional’ hospitals (59%) (Table 2). The ‘larger central’ hospitals presumably have more mental health resources, so this pattern seems counter-intuitive, inviting further study. More generally, however, the legislators' reasoning, successfully operationalised or not, and now embodied in the PHA, runs counter to current medical and public health views that mental, neurological, substance use and suicidal disorders lie along a continuum where disorders caused by substance use cannot rationally be separated from other disorders in binary fashion.26-28 It also runs counter to contemporary critiques of the use of coercive practices in mental health generally and the growing international recognition that the dignity and human rights of people who use drugs is threatened.29 An outcome of the involuntary examination of the person detained in the ED recorded on the prescribed form in only 57% of EEAs implies, disturbingly, that up to 43% of patients may have been deprived of their liberty without the required clinical decision regarding their care.

Less controversially, the pattern of presentations by weekday generally accords with clinical experience except in one feature. In the study region, EEAs may constitute a greater proportion of all presentations to EDs later at night, in line with other behavioural-disturbance type presentations, a result with obvious practical implications for all services.

Finally, sections 157C and 157E of the PHA require QPS and QAS officers and doctors or health practitioners to explain the effect of an EEA to the person ‘in an appropriate way having regard to the person's age, culture, mental impairment or illness, communication ability and any disability’. Nowhere is this required to be recorded on the EEA form. This gap in information regarding cultural identity is of considerable significance in a region where one in five people is Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. An EEA may lead to a community or inpatient treatment authority where Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples are over-represented.30 The inequitable over-representation of black, Asian and minority ethnic groups subject to involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation is widely known.20, 21

Conclusion

Among Australian States and Territories, Queensland is the only jurisdiction where a mental health function is governed under public health legislation; the PHA.5 In light of our results, further detailed examination of the content of EEA forms is warranted. In particular, further analysis of the outcomes of examinations recorded in section 9, part C by clinicians in the ED and of the detailed explanations provided by QPS and QAS officers in section 2, part A of the required form would enrich our understanding of these critical patient encounters.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the research was provided by a ‘seed grant’ from the Tropical Australian Academic Health Centre, James Cook University and by a ‘leading edge grant’ from the Emergency Medicine Foundation (EMLE-103R30-2018-Stone) with funding provided by the State of Queensland through Queensland Health. Support from the Northern Queensland Primary Health Network for ‘Research Capacity Building for Suicide Prevention’ enabled the research to be developed. Funding bodies had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Special thanks to Kristy Grant for coordinating the acquisition of the data. Open access publishing facilitated by James Cook University, as part of the Wiley - James Cook University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. Details about quantitative data are not available from the corresponding author by agreement with the QPS. The views expressed in this material are those of the authors and are not those of the QPS. Responsibility for any errors of omission or commission remains with the authors. The Queensland Police Service expressly disclaims any liability for any damage resulting from the use of the material contained in this publication and will not be responsible for any loss, howsoever arising, from the use of or reliance on this material.

Open Research

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Queensland Health, Queensland Police Service and Queensland Ambulance Service. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of Queensland Health, Queensland Police Service and Queensland Ambulance Service.