Epidemiology and clinical features of emergency department patients with suspected COVID-19: Initial results from the COVID-19 Emergency Department Quality Improvement Project (COVED-1)

Abstract

Objective

The COVID-19 Emergency Department (COVED) Quality Improvement Project aims to provide regular and real-time clinical information to ED clinicians caring for patients with suspected and confirmed COVID-19. The present study summarises data from the first 2 weeks of the study.

Methods

COVED is an ongoing prospective cohort study that commenced on 1 April 2020. It includes all adult patients presenting to a participating ED who undergo testing for SARS-CoV-2. Data are collected prospectively and entered into a bespoke registry. Outcomes include a positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction test result and requirement for intensive respiratory support.

Results

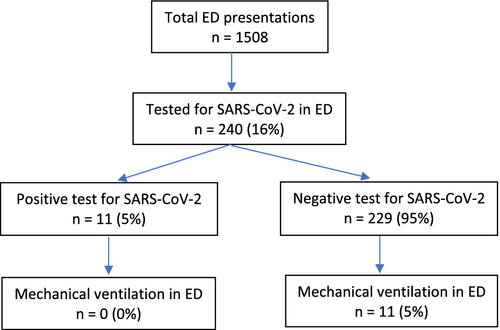

In the period 1–14 April 2020, 240 (16%) of 1508 patients presenting to The Alfred Emergency and Trauma Centre met inclusion criteria. Of these, 11 (5%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The mean age of patients was 60 years and the commonest symptoms were acute shortness of breath (n = 122 [67%]), cough (n = 108 [56%]) or fever (n = 98 [51%]). Overseas travel or known contact with a confirmed case was reported by 24 (14%) and 16 (10%) patients, respectively. Fever or hypoxia was recorded in 23 (10%) and 11 (5%) patients, respectively. Eleven (5%) patients received mechanical ventilation in the ED, of whom none tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusions

Among patients presenting to a tertiary ED with suspected COVID-19, only a small proportion tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Although the low incidence of positive cases currently precludes the development of predictive tools, the COVED Project demonstrates that the rapid establishment of an agile clinical registry for emergency care is feasible.

Key findings

- 16% of patients (n = 240) presenting to the ED in the first 2 weeks of April 2020 were tested for SARS-CoV-2 in the ED.

- Eleven (5%) patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 in the ED had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 prior to or during their hospital presentation.

- Most included patients complained of acute shortness of breath, cough or fever; few patients were febrile or hypoxic in the ED.

- No patients receiving mechanical ventilation or dying in the ED tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

- The COVED Project and COVED registry have laid the foundations, and highlighted the value, of a registry for emergency care.

Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic evolves, there is an ongoing need to support ED clinicians with real-time tools to guide clinical decision making. Public health measures appear to have been effective at flattening the epidemic curve, but the potential for a surge of patients persists.1

Modelling suggests that patients with COVID-19, the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, will continue to present to EDs for many months.1, 2 Although it appears unlikely that Australia's current ED and hospital resources will be overwhelmed, the COVID-19 pandemic will have an impact on community and health system activity, including emergency care, for the majority of 2020.1

Although there are numerous case series and commentaries regarding the natural course of the pandemic, there is a relative paucity of data specific to the ED context.3-7 Given that the number of new COVID-19 cases is likely to wax and wane in response to dynamic public health policies, it remains imperative that ED clinicians have regular, real-time and locally relevant information to inform patient care.

The COVID-19 Emergency Department (COVED) Quality Improvement Project aims to determine the clinical and epidemiological predictors of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result and the requirement for intensive respiratory support among patients presenting to the ED with suspected COVID-19.8 The Project has been designed to be agile, such that it can respond to new information regarding risk factors and treatment strategies. The objective of this analysis (COVED-1) is to report on project feasibility and deliver a synopsis of the results from the first 2 weeks of the study.

Methods

COVED is an ongoing prospective cohort study that commenced on 1 April 2020. The study protocol has been published previously.8

COVED is currently limited to one study site, but other facilities are anticipated to join. The study includes adult patients who meet contemporary testing criteria for COVID-19 and have a SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test requested in the ED. Current and historical Victorian testing criteria are available on the Department of Health and Human Service's website.9 Patients from whom it was not feasible to obtain a history (e.g. persistence of an altered conscious state in the ED) in order to exclude COVID-19 according to the testing criteria, were also tested and therefore included in the study.

This analysis (COVED-1) describes study findings for all eligible patients who presented to The Alfred Emergency and Trauma Centre between 1 and 14 April 2020. The Alfred Hospital is a tertiary, adult, level 1 trauma centre with an annual ED census of approximately 70 000. A co-located but geographically separate screening clinic for COVID-19 was operational during the study period, but not under the governance of the ED. Patients who attended the screening clinic and did not present for medical assessment in the ED were excluded.

As part of the Project, clinical details for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 are collected prospectively using a dedicated form embedded in the hospital's electronic medical record (EMR) system. Data are subsequently entered into a novel registry utilising Research Electronic Data CAPture (REDCap) software (licensed to Monash University).10 Administrative data are exported directly from the EMR.

The EMR form and REDCap database have been designed so that they can be updated with additional variables as new information regarding COVID-19 emerges. Current versions of the data dictionary and case report form are available on The Alfred Hospital's academic programmes website at https://emergencyeducation.org.au/research/coved/.

Outcome measures include a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result and requirement for intensive respiratory support. A complete list of additional variables has previously been published in the study protocol.6 These include history (age, sex, symptoms and duration of presenting complaint, epidemiological features, comorbidities), findings on clinical examination, radiological and blood investigations, care provided in the ED and hospital (including commencement of mechanical invasive ventilation and ED disposition destination) and patient outcomes (including survival to discharge). COVED variables and definitions have been harmonised with international COVID-19 research tools developed by the World Health Organization and International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium.11

For the purposes of this analysis, the summary descriptive statistics have been determined for the pre-specified variables across all patients meeting inclusion criteria. This data has also been stratified by SARS-CoV-2 test result. Among this group of symptomatic patients, the definition of a COVID-19 diagnosis used for COVED-1 was the existence of a positive test result from a SARS-CoV-2 PCR swab taken either prior to, or during the hospital presentation.

According to the study protocol, inferential analyses (comparing predictors and outcomes by SARS-CoV-2 test result, with summary measures of association and 95% confidence intervals) were only to be conducted if the number of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases allowed for a valid analysis. That is not the case at this stage of the Project and COVED-1 is therefore limited to descriptive statistics. Symmetrical numerical data have been summarised using the mean and standard deviation; skewed and ordinal data has been summarised using the median and interquartile range; and categorical data have been summarised using the frequency and percentage. Data were analysed using stata statistical software (version 15.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Ethics approval was obtained from the Alfred Human Research Ethics Committee (Project No: 188/20) on 26 March 2020.

Results

Over the study period of 14 days, there were 1508 presentations to the ED. Of these, 240 (16%) had a SARS-CoV-2 test ordered and were included in this analysis. Eleven (5%) patients had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result either prior to or during their episode of hospital care (Fig. 1).

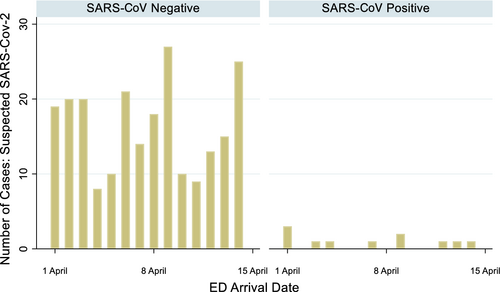

The daily number of eligible patients presenting to the ED remained relatively stable over the study period. Figure 2 displays this data, stratified by SARS-CoV-2 test result.

Table 1 describes the clinical features of patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 PCR swab testing in the ED. The mean (standard deviation) age was 60 (21) years, and 133 (55%) were male. There were three (1%) patients transferred from another hospital, and 142 (59%) arrived by road ambulance. The most frequent triage category assigned was category 3 (n = 117 [49%]), followed by category 2 (n = 68 [28%]).

| Variable | Missing, n (%), n = 240 | Subgroups | All cases of suspected COVID-19 (n = 240) | SARS-CoV-2 test positive† (n = 11) | SARS-CoV-2 test negative (n = 229) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 0 (0) | 60 (21) | 51 (18) | 61 (21) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0 (0) | Male | 133 (55) | 8 (73) | 125 (55) |

| Transfer from other hospital, n (%) | 0 (0) | Yes | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Mode of transport, n (%) | 0 (0) | Ambulance – road | 142 (59) | 3 (27) | 139 (61) |

| Ambulance – helicopter | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | ||

| Public transport | 17 (7) | 1 (9) | 16 (7) | ||

| Private transport/other | 78 (33) | 7 (64) | 71 (31) | ||

| Triage category, median (IQR) | 0 (0) | 3 (2,3) | 3 (3,3) | 3 (2,3) | |

| Triage category, n (%) | 1 | 11 (5) | 0 (0) | 11 (5) | |

| 2 | 68 (28) | 1 (9) | 67 (29) | ||

| 3 | 117 (49) | 9 (82) | 108 (47) | ||

| 4 | 43 (18) | 1 (9) | 42 (18) | ||

| 5 | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | ||

| Presenting complaint, n (%) | |||||

| Shortness of breath | 56 (23) | Yes | 122 (66) | 8 (80) | 114 (66) |

| Cough | 45 (19) | Yes | 108 (55) | 6 (67) | 102 (55) |

| Change to chronic cough | 105 (44) | Yes | 15 (11) | 1 (14) | 14 (11) |

| Anosmia or dysgeusia | 160 (67) | Yes | 8 (10) | 1 (17) | 7 (9) |

| Sore throat | 87 (36) | Yes | 51 (33) | 2 (29) | 49 (34) |

| Runny nose | 104 (43) | Yes | 36 (26) | 3 (43) | 33 (25) |

| Fever | 46 (19) | Yes | 98 (51) | 4 (44) | 94 (51) |

| Fatigue | 140 (58) | Yes | 62 (62) | 9 (100) | 53 (58) |

| Myalgia | 129 (54) | Yes | 39 (35) | 6 (60) | 33 (33) |

| Diarrhoea | 101 (42) | Yes | 25 (18) | 7 (70) | 18 (14) |

| Other | 43 (18) | Yes | 115 (58) | 4 (36) | 110 (60) |

| Number of days since first symptom, median (IQR) | 25 (10) | 3 (1,7) | 7 (5,21) | 3 (1,7) | |

| Other relevant history, n (%) | |||||

| Overseas in previous 28 days | 67 (28) | Yes | 24 (14) | 6 (60) | 18 (11) |

| Contact with confirmed case | 78 (33) | Yes | 16 (10) | 5 (56) | 11 (7) |

| Residential aged care facility | 46 (19) | Yes | 17 (9) | 0 (0) | 17 (9) |

| Healthcare worker | 51 (21) | Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Previous SARS-CoV-2 swab† | 1 (1) | SARS-CoV-2 positive | 6 (3) | 6 (55) | 0 (0) |

| SARS-CoV-2 negative | 18 (8) | 0 (0) | 18 (8) | ||

| Swab result unknown | 16 (7) | 1 (9) | 15 (7) | ||

| No prior swab | 199 (83) | 4 (36) | 194 (86) | ||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Chronic respiratory | 66 (28) | Yes | 62 (36) | 2 (18) | 60 (37) |

| Obesity | 145 (60) | Yes | 25 (26) | 1 (14) | 24 (27) |

| Smoker | 114 (48) | Yes | 54 (43) | 4 (50) | 50 (42) |

| Chronic cardiac | 63 (26) | Yes | 69 (39) | 2 (18) | 67 (40) |

| Hypertension | 69 (29) | Yes | 73 (42) | 2 (18) | 71 (44) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 76 (32) | Yes | 36 (22) | 1 (9) | 35 (23) |

| Malignant neoplasm | 69 (29) | Yes | 26 (15) | 1 (9) | 25 (16) |

| Immunosuppression | 80 (33) | Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 9 (4) | Yes | 61 (26) | 3 (27) | 58 (26) |

| Examination – first vital signs in ED | |||||

| Temperature (°C), mean (SD) | 1 (0) | 36.8 (0.9) | 36.7 (0.6) | 36.8 (0.9) | |

| Fever recorded (temperature ≥38°C), n (%) | Yes | 23 (10) | 0 (0) | 23 (10) | |

| SaO2 (%), mean (SD) | 9 (4) | 97 (4) | 97 (5) | 97 (4) | |

| Hypoxia (SaO2 <92%), n (%) | Yes | 11 (5) | 1 (10) | 10 (5) | |

| SBP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 8 (3) | 140 (29) | 142 (29) | 139 (29) | |

| Hypotension (SBP <100 mmHg), n (%) | Yes | 15 (6) | 1 (10) | 14 (6) | |

| Examination – other | |||||

| Abnormality on chest auscultation,‡ n (%) | 99 (41‡) | Yes | 53 (38) | 2 (67) | 51 (37) |

- † SARS-CoV-2 positive cases are defined in COVED-1 as having a positive SARS-CoV-2 test either prior to or during their hospital presentation.

- ‡ May not have been performed.

- IQR, interquartile range; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Regarding the patient's history and clinical examination, the most common presenting complaints were acute shortness of breath (n = 122 [66%]), acute cough (n = 108 [55%]) or acute fever (n = 98 [51%]). The median (interquartile range) number of days between first symptom and ED presentation was 3 (1–7) days. A minority of patients who underwent testing in the ED reported epidemiological features potentially predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection: overseas travel in previous 28 days (n = 24 [14%]), contact with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 case (n = 16 [10%]), and living in a residential aged care facility (n = 17 [9%]). There were no healthcare workers in the study sample. Almost one-fifth of patients (n = 40 [18%]) had been tested for SARS-CoV-2 prior to their ED presentation, of whom six (3%) were reported to be SARS-CoV-2 positive. Few patients were hypoxic (SpO2 <92%) (n = 11 [5%]) or hypotensive (systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg) (n = 15 [6%]) on their initial vital signs in the ED.

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for the investigations, care and outcomes of patients for whom a SARS-CoV-2 PCR swab test was conducted in the ED. There were 205 (85%) patients who had a chest X-ray radiograph, 18 (9%) of which were reported by a radiologist as having bilateral infiltrates. According to blood tests performed in the ED, 75 (33%) had a leucocytosis and 53 (27%) had a C-reactive protein of greater than 50.

| Variable | Missing, n (%), n = 240 | Subgroups | All cases of suspected COVID-19 (n = 240) | SARS-CoV-2 test positive† (n = 11) | SARS-CoV-2 test negative (n = 229) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investigations – imaging | |||||

| CXR abnormal, n (%)‡ | 35 (15‡) | Yes – bilateral infiltrates | 18 (9) | 4 (40) | 14 (7) |

| Yes – other abnormality | 69 (34) | 1 (10) | 68 (35) | ||

| No | 118 (58) | 5 (50) | 113 (58) | ||

| CT chest abnormal, n (%)‡ | 212 (88‡) | Yes – bilateral infiltrates | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Yes – other abnormality | 15 (54) | 0 (0) | 15 (54) | ||

| No | 13 (46) | 0 (0) | 13 (46) | ||

| Investigations – blood tests‡ | |||||

| WCC, mean (SD) | 15 (6) | 10 (5) | 7 (3) | 10 (5) | |

| Leucocytosis (WCC >11.0), n (%) | Yes | 75 (33) | 1 (10) | 74 (34) | |

| C-reactive protein, mean (SD) | 45 (19) | 47 (76) | 67 (99) | 46 (75) | |

| C-reactive protein >50, n (%) | Yes | 53 (27) | 5 (56) | 48 (26) | |

| Emergency care, n (%) | |||||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation in ED | 1 (0) | Yes | 11 (5) | 0 (0) | 11 (5) |

| Disposition destination from ED | 0 (0) | Died in ED | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| ICU | 12 (5) | 1 (9) | 11 (5) | ||

| Ward (not ICU) | 127 (53) | 5 (45) | 122 (53) | ||

| ESSU | 53 (22) | 1 (9) | 52 (23) | ||

| Home | 42 (18) | 4 (36) | 38 (17) | ||

| Other (including transfer) | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | ||

| Disposition destination from hospital | 0 (0) | Died in hospital | 12 (5) | 0 (0) | 12 (5) |

| Residential aged care facility | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | ||

| Home | 181 (75) | 9 (82) | 172 (75) | ||

| Transfer to other hospital | 17 (8) | 0 (0) | 17 (7) | ||

| Discharge against medical advice | 8 (3) | 0 (0) | 8 (3) | ||

| Inpatient at end of study period | 19 (8) | 2 (18) | 17 (7) | ||

- † SARS-CoV-2 positive cases are defined in COVED-1 as having a positive SARS-CoV-2 test either prior to or during their hospital presentation.

- ‡ May not have been performed.

Mechanical ventilation was commenced in the ED for 11 (5%) patients, but none had a positive result for SARS-CoV-2. From the ED, 127 (53%) patients were admitted to the general ward, 12 (5%) to the ICU and 42 (18%) were discharged home. During the study period, 12 (5%) patients died in hospital, of which none had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Discussion

The COVED Project aims to provide ED clinicians with contemporary data regarding the care and outcomes of ED patients with suspected and confirmed SARS-CoV-2. The rapid establishment of a clinical form embedded in the EMR and a bespoke, electronic clinical registry has enabled real-time data capture and early reporting.

Since the inception of the Project, the daily number and proportion of patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test has remained relatively small. In the midst of a pandemic, with a devastating impact on mortality and health system capacity in multiple countries, this is an important and welcome finding.3-7 Nevertheless, there will continue to be patients presenting to EDs with COVID-19, and the risk of a surge in ED presentations remains for the medium term.

The small number of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases (n = 11) to date limits confidence in identifying those epidemiological factors, clinical features and outcomes that distinguish SARS-CoV-2 positive from SARS-CoV-2 negative patients. Among patients presenting to ED with suspected SAR-CoV-2 infection, most patients with a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 reported recent overseas travel and/or contact with a confirmed case. This is consistent with the Australian epidemiological experience of COVID-19, where the majority of the cases have been from overseas exposure with limited community spread and justifies the requirement for ongoing rigorous screening of overseas travellers.12

When reported, fatigue was universally present as a complaint in all patients who were SARS-CoV-2 positive and should be sought in the assessment of potential COVID-19 patients. Fever was not present in any patient who tested positive. If validated over a longer period, these findings would question the relevance of widespread temperature screening that is being practised in health facilities. These early results also suggest initial leucocytosis or a raised C-reactive protein are inadequate discriminators for positive SARS-CoV-2 status.

Among positive cases, with only one patient admitted to the ICU and no in-hospital deaths, it appears the outcome of COVID-19 patients in Australia may be favourable compared to other countries.3-7 This finding is reflected in broader Victorian state data.12

Currently, while the ED caseload of SARS-CoV-2 infection remains low, the COVED registry is serving as a registry for emergency care (REC), with a focus on patients with acute respiratory infection. The COVED registry also adds value by providing information around the current burden of suspected COVID-19 patients in the hospital system. The isolation procedures for these patients stipulate that they are managed as if SARS-CoV-2 positive until the results of a negative test are returned. While these infection control measures are warranted, the significant numbers of suspected cases may have a negative impact on overall system efficiency.

When the current COVID-19 pandemic dissipates, the demand for an ongoing source of contemporary clinical information and sentinel surveillance in EDs will persist. A REC, therefore, is likely to have a future role as a source of real-time clinical data to guide emergency care delivery and public health response, especially in the setting of communicable disease outbreaks.13

Limitations

The low incidence of SARS-CoV-2 positive results over the early weeks of the COVED Project has precluded valid inferential analyses regarding how COVID-19 patients differ in terms of their demographic features, clinical presentation, severity risk factors, need for intensive respiratory support and key outcomes. While some percentages displayed in Tables 1 and 2 may vary between those who have had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test and those who do not, these figures should be interpreted with caution.

Missing data is an issue for some variables, and more work is required to increase the level of data completeness for those variables extracted manually from the EMR form used by ED clinicians. Other sources of missing data are expected as the COVED Project progresses and reflect that some variables of emerging clinical interest will be subsequently added for data collection, COVID-19 testing criteria change frequently, and that patients being tested for COVID-19 may not undergo an identical suite of investigations.

Conclusions

Among patients presenting to a tertiary ED with suspected COVID-19, only a small proportion had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2. Although the low incidence of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases currently precludes the development of predictive tools, the COVED Project demonstrates that the rapid establishment of an agile clinical REC is feasible.

Acknowledgements

GMOR is currently a NHMRC Research Fellow at the National Trauma Research Institute, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, leading the project titled: Maximising the usefulness and timeliness of trauma and emergency registry data for improving patient outcomes. The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable advice and assistance in data management from the following contributors: Mr John Liman (Monash Helix), Ms Jane Ford (Alfred Trauma Registry), Ms Bismi Jomon and Ms Pratheeba Selvam (Alfred Data and Analytics).

This article was prepared by the authors and reflects their expert, consensus opinion. A decision not to externally peer review the article was taken by the Editor in Chief and reflects the urgent need to expedite publication and dissemination of guidance for clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Competing interests

GMOR, BM and PAC are section editors for Emergency Medicine Australasia.