Theoretical and empirical perspectives on the link between poverty, parenting and children's outcomes

Submitted: November 2024

Funding information:

ESRC Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at IFS: ES/T014334/1

Abstract

In this paper we examine different channels through which poverty affects child outcomes, as well as the evidence regarding the magnitude of their impacts. We begin by discussing the family investment model, which highlights the constraints that poverty or lack of income pose on a family's ability to purchase goods or services that contribute to the child's overall development, and the family stress model, which emphasises the emotional toll that experiencing poverty can have on parents and (directly and indirectly) on children. We then devote special attention to a more recent perspective on the family stress model, originating at the intersection of cognitive and developmental psychology and behavioural economics, which posits that another pathway through which poverty-induced stress can affect family well-being is through the effect of poverty on parental cognitive functioning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Across the world, children growing up in poverty are more likely to live their adult lives in substantial disadvantage relative to those not growing up in poverty (e.g. Duncan and Brooks-Gunn, 1999; Duncan et al., 2019). The degree to which childhood disadvantage becomes adult disadvantage varies widely across countries and is subject of a large literature on social mobility. The UK comes out consistently as one of the least socially mobile countries in the developed world (e.g. Corak, 2013; OECD, 2018). This means that it is harder for a poor child to escape a life of poverty in adulthood in the UK than almost anywhere else in the developed world.

There also seems to exist a negative correlation across countries between social mobility and inequality, which is usually called the Great Gatsby Curve (e.g. Corak, 2013). The UK is typically placed at one of the extremes of this curve, with low levels of social mobility and high inequality. Furthermore, if anything, social mobility in the UK has been falling over time (e.g. Blanden et al., 2005; Blanden, Gregg and Macmillan, 2007; van der Erve et al., 2024). This problem is especially acute in the UK because it is a country not only with high levels of inequality, but also with a large number of families living in poverty. At the time of writing, the latest data available for the UK show that the rate of relative child poverty is a staggering 30 per cent, corresponding to 4.3 million children (Henry and Wernham, 2024).

While there exists a large literature documenting correlations between family income and a wide range of child outcomes, two important questions arise from this evidence. First, to what extent does money – or lack thereof – matter for child development? Second, if money does have a causal impact on children's outcomes, what mechanisms underpin this relationship? The answers to these two questions are fundamental to identify and design policies that improve the outcomes of children growing up in poorer environments and reduce the gap between them and their more affluent peers.

In this paper, we discuss the recent literature that speaks to these two questions, with a particular focus on parenting. We refer to parenting broadly as the set of decisions that parents make about investing their money and time and that have consequences for their children's outcomes (whether parents and carers are conscious or not of the consequences that these decisions have on their children). Importantly, the impact of these decisions on children's outcomes will reflect and be influenced by the information, attitudes and beliefs parents have about child-rearing, as well as their cognitive, emotional and physical capabilities (Grusec and Danyliuk, 2014; Attanasio, Cattan and Meghir, 2022).

First, we discuss the evidence on the extent to which there is a causal impact of family income on children's outcomes. The other two articles in this symposium (Aizer and Lleras-Muney, 2025; Michelmore, 2025), as well as other recent literature reviews on the impact of family on children's outcomes (Cooper and Stewart, 2013, 2017, 2021; Duncan et al., 2019; Page, 2024), provide a comprehensive assessment of the current literature on the impact of income on children's outcomes. We therefore only briefly summarise their findings. In addition, we present novel descriptive evidence for the UK, where we decompose the family income gradient in child outcomes into components that are attributable to characteristics that are predetermined to family income – and therefore are potentially related to the determinants of family income – versus other characteristics, which instead can be a result of the level of family income in the family. We use rich data on the outcomes and environments of a nationally representative cohort of children born in the UK in the early 2000s, the Millennium Cohort Study, hereafter MCS (University College London, UCL Institute of Education, Centre for Longitudinal Studies, 2024).

This exercise, combined with our own reading of the literature, suggests that while the weight of the evidence points to a positive causal effect of family income on children's outcomes, it is much less clear from the evidence how far income transfers between poor and non-poor children could go in closing outcome gaps between them.

On the one hand, the estimates of the effect of income on outcomes reviewed and compared in Page (2024) suggest that income transfers can have large impacts on child outcomes. If these impacts were to hold across the income distribution, they could imply that all of the outcome gap could, in theory, be closed by closing the income gap between children at various points of the distribution.

However, for this to be true, the effect of income estimated in samples of children at the bottom of the income distribution would need to hold at higher points of the income distribution. As Page (2024) argues, this is unlikely – though we still do not have a good estimate of the impact of the income at different points of the distribution.

On the other hand, the evidence from the MCS suggests that most of the family income gradient in child outcomes is explained by parental and household characteristics, such as maternal age at child's birth, maternal education and family structure, which are predetermined and likely to affect family income when a child is growing up. While the evidence we present from the MCS does not aim to estimate a causal effect of income, at face value, it would also suggest that, while income transfers can improve outcomes, there is a limit to how much they can improve children's outcomes.

Importantly, this evidence does not mean that income transfers should not be carried out. Welfare benefits in cash or in-kind may well have a positive rate of return and hence be worthwhile economic investments, providing more benefits than they cost (and obviously there may also be non-economic arguments for investing in reducing child poverty too). However, more research about the impact of income at higher points of the distribution is urgently needed to help policymakers calibrate the size of transfers needed to help achieve their goals.

Our reading of this evidence is that the correlation between poverty and child outcomes is more likely to be driven by long-term family factors crystallised in the home environments experienced by children during their entire childhood (or even reflected in their genes, and the interaction of genes and environments). Home environments can in turn be a consequence of income and wealth, but also (and perhaps primarily) of parental characteristics such as their skills and personality traits. Carneiro et al. (2021) also document that permanent income is much more important than income fluctuations (and their timing) in predicting child outcomes. This is not a surprising result: typically, one would expect larger impacts of permanent changes to income, which have long-lasting effects, than (similarly sized) transitory income fluctuations, which only last for a short period of time.

There are several potential mechanisms through which shifts in income have causal impacts on child development. We review three theoretical perspectives that potentially explain these mechanisms. The first two – the investment pathway and the family stress pathway – have been extensively explored in the literature. Under the investment pathway, poverty limits what parents can buy to enhance their children's development (e.g. Becker, 1993, among others). Under the family stress pathway, poverty creates emotional stress and worry that affect the way parents interact with their children; see, for example, the discussions in Shonkoff, Slopen and Williams (2021), McLaughlin, Weissman and Bitrán (2019) and McEwen and McEwen (2017), among many others. A third, more recent theoretical perspective, originating in behavioural economics and building on insights from scarcity theory (Mani et al., 2013; Mullainathan and Shafir, 2013), posits that poverty affects children's outcomes by impeding parental cognitive functions and the quality of parental decision-making (Gennetian, Darling and Aber, 2016; List, Samek and Suskind, 2018; Kalil and Ryan, 2020; Mayer, Kalil and Klein, 2020). This strand of the literature identifies a number of cognitive biases, such as present bias and attribution bias, which distort parental investment decisions away from what is most optimal for their children's development.

After reviewing these theoretical perspectives, we discuss existing empirical evidence supporting each of them. With respect to the family investment and family stress models, we focus on experimental and quasi-experimental studies on the causal impact of money on different dimensions of material/monetary investments and on family stress and parental mental health. The empirical evidence on the behavioural science of parental decision-making is still in its infancy, but we summarise a number of recent and ongoing studies that speak to this interesting perspective. We note two strands in this literature. One consists of a handful of studies interested in demonstrating that financial worry causally affects parental decision-making about investment in children. The other set of studies evaluates the impact of parenting interventions designed to counter specific cognitive biases.

We conclude the paper with remarks on what this theoretical and empirical evidence implies for the role of anti-poverty policy to promote child outcomes. Such a discussion is particularly timely in the context of the UK as the newly elected government has formed a cross-government child poverty taskforce to set a strategy to come out soon after the publication of this paper.

A central premise of our paper is that parents have a substantial influence on their children's development. The money and time they invest in their children, how they interact with them, and all the other decisions they make that contribute to creating a particular environment in which their children grow up play an important role in shaping the way their children develop. This premise is supported by a large multi-disciplinary literature that documents correlations between environmental and parental factors and child outcomes, as well as more causal evidence of interventions that shift both parenting and child outcomes.1

2 TO WHAT EXTENT DOES MONEY MATTER FOR CHILDREN'S OUTCOMES?

A large literature establishes that money matters for child development. Although this sounds like an obvious statement, up until recently there were not many credible studies on this issue that demonstrated that money did indeed matter. In other words, it was not clear that providing income transfers to the poor would have significant impacts on child development (e.g. Mayer, 1998).

A number of recent papers comprehensively review the literature that most convincingly establish a causal link between family income and children's outcomes via quasi-experimental and experimental designs. Duncan et al. (2019) and more recently Page (2024) summarise and critically appraise this literature, and the other two papers in this Symposium offer in-depth reviews of particular types of policies that have historically been used to fight child poverty. Aizer and Lleras-Muney (2025) focus on cash and in-kind benefits (nutrition, early childhood education, housing and health care) and their impacts on children's health, wellbeing and adult outcomes. Michelmore (2025) discusses policies that encourage or require work, specifically work tax credits, and the large evidence drawing on shifts in policies in the UK, the US and Canada, and their impacts on children's outcomes.

While we agree with all these reviews that the weight of the evidence points to a causal effect of family income on children's outcomes, much less is clear about its quantitative implications for how much income gaps are responsible (in a causal sense) for children's outcomes gaps. Most papers in this literature report an effect size (and whether it is statistically significant) that indicates how large an effect an exogenous shift in family income has on children's outcomes. However, there are methodological challenges to extrapolating from these findings what shift in family income would be necessary to close the family income gaps in children's outcomes, and very few studies even discuss this. Moreover, the literature offers a wide range of estimates of the impact of family income on children's outcomes, making it difficult to generalise – though, as we discuss below, Page (2024) does an excellent job at presenting the wide variety of estimates in the most comparable fashion.

Although we cannot fully answer this question in this paper, we nevertheless present some suggestive evidence of the importance of income versus other factors in explaining these outcomes gaps. In order to do so, we present an original analysis of data from the MCS, a nationally representative survey of about 19,000 children born between 2000 and 2002, and their families. We use very detailed information available in this data set on children's cognitive and socio-emotional development at ages 3 and 7, child and parent characteristics, family income, and parenting behaviours and investments. The variables used in our analysis are described in detail in the online Appendix.

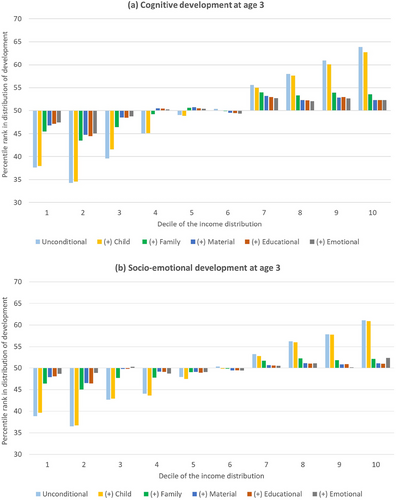

In Figure 1, we document income gradients in cognitive (panel a) and socio-emotional (panel b) development at age 3. Higher scores in cognitive and socio-emotional development (i.e. higher percentile ranks) indicate higher cognitive skills and fewer emotional and behavioural difficulties, respectively, as measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. We split the sample of children and families into ten groups, corresponding to ten family income deciles (income is measured at age 3), labelled 1 to 10 on the horizontal axis of the figure.

Income inequalities in child development at age 3 before and after controlling for income inequalities in early childhood environments. Note: The first bar shows the unconditional percentile rank of development scores by income decile, based on equivalised household income at age 3. Subsequent bars add controls sequentially for child and family characteristics, as well as the material, educational and emotional environments in which the child is raised. The estimation sample is consistent across all regressions and weighted to be representative of the UK population.

For children in each income decile, we begin by computing the average cognitive percentile rank for children in each group (the bar labelled ‘unconditional’). Unsurprisingly, there is a strong income gradient in cognitive scores. Children in the bottom two deciles score between percentiles 35 and 40 of the cognitive test score distribution, whereas those in the top two deciles are ranked 25 percentiles higher. When looking at socio-emotional development, gaps in behaviour between high- and low-income children are quite similar to the ones reported for cognitive skills.

Such income gaps can be due to material poverty, but they can also be due to many of the correlates of material poverty, such as the characteristics of parents who are poor; for example, these parents often have lower education levels, lower levels of cognitive and socio-emotional skills, and are more likely to be single parents than their wealthier counterparts. Holding family income constant, these factors could all be hypothesised to influence child development. It is therefore difficult to attribute income gaps in child development solely to income differences across families.

For this reason, most studies emphasised in Duncan et al. (2019), Page (2024) and the other two papers of this symposium explore experimental or quasi-experimental variation in family income to identify the impact of income on child development. We are unable to replicate such analysis in our data set and instead present a more descriptive and very much correlational, but still interesting, set of results, which relies on very detailed data on parent and child characteristics, as well as the environments they live in. Below we examine what happens to the unconditional income gradients in cognitive and socio-emotional development discussed above when we account for differences in other parental characteristics, including parents’ education, their cognitive and socio-emotional skills, and family structure, among others (slightly expanding similar analysis in Cattan et al., 2024).

Therefore, in the second set of bars in the two panels of Figure 1, labelled ‘(+) Child’, we control for child characteristics, such as age (measured in months of age at the time of the survey), gender, whether the child is first born, and ethnicity. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these characteristics make very little difference. Children in this cohort study are roughly of similar age. Moreover, age, gender and parity should not correlate with income. We would have hypothesised that ethnicity correlates with both parental income and child outcomes, but the results presented here suggest that ethnicity does not have a large impact on this decomposition.

The set of bars labelled ‘(+) Family’ corresponds to income gradients in skills after controlling for a range of family demographics: mother's age at the time of birth of the child, mother's body mass index, family structure, mother's education and mother's language skills. All these variables are correlated with income, but some of them are likely to be determinants of income and likely also to affect children's skills (over and beyond their impact on income). Figure 1 shows that once we control for these variables, the income gradient in early skills drops sharply.

This latter gradient measures the association between income and child skills for children and families with the same characteristics. It is a useful benchmark, which we can compare with what fraction of the poor/non-poor differences can potentially be explained with the estimates of the causal impact of income on child development taken from the literature we mentioned above, especially shorter-term income transfers (as we presumably capture much of the more permanent family income with the controls we include). The bottom line from this figure (and from our reading of the literature on the causal impact of income on child development) is that only a small fraction of the unconditional family income–child development gradient can be attributed to the causal impact of short-term income shocks, and can potentially be addressed through income transfers (unless they have a more permanent character – and, even in that case, we cannot distinguish the role of permanent income from the role of other permanent family factors).

In the remaining three bars, we present the family income gradient in cognitive skill, conditional on parental behaviours and investments that proxy for different aspects of the home environment. In particular, we include controls for the child's material environment (capturing housing quality and overcrowding), educational environment (a combination of formal childcare use and maternal cognitive stimulation) and emotional environment (maternal mental distress, parent–child relationship quality, regularity of bedtimes and inter-parental conflict). Although parental income can have causal impacts on some of these variables, which can then mediate the impact of parental income on child outcomes, there is likely to be substantial variation in these dimensions of the home environment that are independent of parental income. So, they partially capture impacts of parental income. After controlling for these variables, the income gradients in cognitive and non-cognitive skills at age 3 disappear, perhaps because these variables capture all the channels through which income correlates with child development.

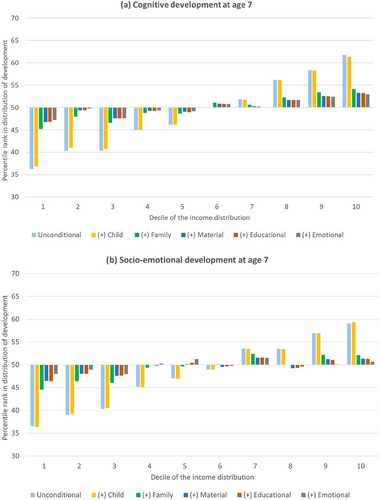

Figure 2 replicates what we see in Figure 1, but for cognitive and socio-emotional development at age 7. We can account for most of the income gradient in child development by controlling for variables that are presumably determinants, but not causes, of parental income (although we recognise that family structure could potentially be a consequence of family income shocks). We can account for the remainder of this gradient by controlling for variables that partially reflect that causal impact of income on child outcomes and partly reflect the impact of other factors.

Income inequalities in child development at age 7 before and after controlling for income inequalities in early childhood environments. Note: The first bar shows the unconditional percentile rank of development scores by income decile, based on equivalised household income at age 7. Subsequent bars add controls sequentially for child and family characteristics, as well as the material, educational and emotional environments in which the child is raised. The estimation sample is consistent across all regressions and weighted to be representative of the UK population.

How does this evidence tally against the literature aiming to estimate the causal impact of family income on child outcomes? To shed light on this question, we return to the excellent study of Page (2024), who presents the estimates of the impact of family income on a number of children's outcomes across existing experimental and quasi-experimental studies in the most comparable way possible. Her conclusion from this exercise – which we agree with – is that while most studies point toward economically meaningful effects, ‘we do not have enough information yet to make firm claims about exact magnitudes and how they vary across the income distribution, or whether income interventions are more impactful when they occur in certain environments.’

Her analysis does highlight that most papers that find an economically significant effect are those where the income transfer is predictable and regular. These studies are based on income transfers that arise from policies such as tax credits (e.g. the EITC in the US) and child benefits. While Page (2024) helpfully translates the impacts found in these studies in terms of the impact of a $1,000 shift in family income on children's outcomes, the actual design of the transfer and the duration of the period the transfers are made are therefore likely to play an important role in driving the impacts found. A one-time lump-sum transfer of $1,000 is likely to have a lower effect than a transfer amounting to the same amount that would be disbursed in regular and predictable (smaller) instalments.

While the literature still needs to provide more robust evidence on this question, the takeaway that transfers are likely to have a greater impact if they are regular and predictable is consistent with the empirical evidence we presented above for the UK. In Figure 1, we showed that inequalities in child outcomes between children at the different points of the family income distribution when they are age 3 are mostly explained by long-term factors, such as maternal education, skills and age at birth, as well as family structure. These factors are more likely to be correlated with (and to affect) the permanent – and more predictable – component of income than transitory factors. Nevertheless, it is also possible that permanent income is not an important long-term causal determinant of child outcomes, and that other components of the home environment are more important instead.

There remains an important question about the impact that even optimally designed cash transfers can have on inequality in child outcomes. As Page (2024) reviews, the magnitude of impacts found in some papers (e.g. Duncan et al., 2011; Milligan and Stabile, 2011; Dahl and Lochner, 2012) is such that an annual increase in $1,000 (about $1,255 or £1,030 in 2024–25 prices) leads to an improvement in children's outcomes of between 0.03 and 0.07 standard deviations (SD). If we include the studies that find zero impacts, the average effect of family income on child outcomes found across the seven papers reviewed by Page (2024) is about 0.015 SD.

To put these numbers in perspective, in the cohort study we analyse here (i.e. the MCS), the gap in cognitive skills at age 3 between children at the first and fifth deciles of the family income distribution is 0.39 SD, and the gap between children at the fifth and tenth deciles is 0.49 SD. The 2023 UK income distribution is such that the difference in annual net equivalent disposable household income (before housing costs) for a couple with two children under 14, is about £23,000 (in 2023–24 prices) between the 10th and 50th decile, and £45,000 pounds between the 50th and 90th decile (Department for Work and Pensions, 2024).

A back-of-the-envelope calculation using the average estimate of the impact of family income would therefore suggest that transferring income to families in the lowest deciles of the distribution could substantially lift children's outcomes, but closing gaps in outcomes between, say, children at the 10th and 50th percentile of the income distribution would require substantial transfers (even generous programmes, such as the Scottish Child Payment that pays £26.70 per week per child, would pay about £4,000 for a family of three, helping to close the gap but still going only part of the way). Assuming that the effects estimated in these studies are linear across the income distribution, closing the outcome gap would essentially require closing the income gap entirely. In other words, under linearity, income differences could potentially explain the entirety of the family income gap in child outcomes, although this is more likely if we refer to permanent rather than temporary family income differences. As discussed in Page (2024) however, the evidence points to important non-linearities in the impact of income transfers on children's outcomes where the effect would be decreasing with income. If that is the case, then the transfers that would be required to close the inequalities in outcomes between children at different points of the distribution would be even larger than if the effect of income on outcomes was linear. Gaining a better understanding of the impact of family income on children's outcomes at different points of the distribution seems like an urgent priority to better inform the design of welfare benefits.

How much income transfers can and will affect children's outcomes will depend on the channels that underlie this impact and whether or not they are activated in the way cash is distributed. We turn to discuss this in the remainder of the paper.

3 MECHANISMS UNDERLYING THE LINK BETWEEN FAMILY INCOME AND CHILD OUTCOMES: THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

In this section, we review three key theoretical perspectives on the question before turning to the empirical evidence for each of them in the next section.

Two major models have been traditionally used to explain why family income might influence (in a causal sense) child outcomes. The first, the family investment model, highlights the constraints that poverty or lack of income pose on a family's ability to purchase goods or services that contribute to the child's overall development (Becker, 1993; Conger and Donnellan, 2007; Conger, Conger and Martin, 2010). In an economic model of household behaviour where child development responds to different inputs or investments, the family investment pathway highlights the way through which family income – or lack thereof – affects the quantity and quality of monetary investments parents can make and that have an impact on their child's human capital development. These investments may include necessities, such as safe housing, basic healthcare and nutritious food, as well as access to quality education, extracurricular activities, health care, and items to create a safe and stimulating home environment.

The second theoretical perspective – the family stress model – emphasises the emotional toll that experiencing poverty can have on parents and (directly and indirectly) on children. Boss, Bryant and Mancini (2017) define family stress as a ‘disturbance in the steady state of the family system’, where such a disturbance may be due to external factors (e.g. unemployment) or internal factors (e.g. divorce). According to the family stress model, financial worry and the emotional strain of not having enough or having insecure resources for day-to-day living often result in less effective parenting practices, such as reduced warmth and bonding, less engagement in play, increased conflict, inconsistent discipline and/or punitive or unresponsive parenting styles (Acquah, 2017). Conger and colleagues identify a number of cascading pathways through which financial stress can disrupt family functioning, including increased frustration, psychological distress, and aggressive and conflictual interactions between members of the family (Berkowitz, 1989; Conger, Conger and Martin, 2010).

A more recent perspective on the family stress model, originating at the intersection of cognitive and developmental psychology and behavioural economics, posits that another pathway through which poverty-induced stress can affect family well-being is through the effect of poverty on parental cognitive functioning. At its root is an application of the Mullainathan and Shafir (2013) scarcity theory to parental decision-making. Scarcity theory posits that poverty induces a scarcity mindset, whereby the experience of tight budgets and insecure income streams requires the poor to focus on immediate and pressing shortages, which limit their ability to plan, make decisions or consider long-term goals. When people operate under a scarcity mindset, they focus on alleviating urgent needs, which depletes them from elementary cognitive resources, such as attention, executive control and working memory. As a result, they have fewer cognitive resources left to address non-pressing but equally important demands. This ‘tunnelling effect’ and the subsequent lack of mental bandwidth it creates is, according to scarcity theory, what forces the poor into counterproductive behaviours that perpetuate the condition of poverty.

Applying these concepts to parenting, a number of behavioural economists and developmental psychologists argue that parental decision-making may be particularly prone to being affected by a poverty-induced scarcity mindset (Gennetian, Darling and Aber, 2016; List, Samek and Suskind, 2018; Kalil and Ryan, 2020; Mayer, Kalil and Klein, 2020). According to Mayer, Kalil and Klein (2020), there are at least four features that make parental decision-making prone to cognitive biases. First, parents often have to make decisions that involve temporal trade-offs, as the effect of many present decisions does not ‘show up’ in children's outcomes immediately, but only much further in the future. Second, parental decisions require attribution (i.e. require understanding/interpreting others’ perspectives and emotions). Third, many decisions parents need to make are quick and on-the-spot and therefore result in automaticity. Lastly, the decisions parents make in relation to their children are often experienced as identity-relevant. While there is still little research on what role that parents’ identities play in parenting decisions or child outcomes, the fact that parenting primes different and potentially conflicting identities (e.g. as a parent, as a wife, as a career professional, as unemployed, as a single parent) means that parents may be led to make investment decisions that are not internally consistent or consistently child-development-enhancing.

These features make parents’ decisions particularly complex and prone to a number of cognitive biases. The beELL initiative directed by Lisa Gennetian offers a codex of parenting cognitive biases, which includes many of the biases identified in Mayer, Kalil and Klein (2020) and Kalil and Ryan (2020). We summarise them here.

The fact that parenting decisions often involve temporal trade-offs makes parenting decisions subject to ‘present bias’: they prioritise immediate rewards or gratification over future benefits, when the future benefits are objectively more significant. When parents are present biased, they might prioritise activities that are more rewarding for themselves and their children in the present (e.g. watching TV and seeing your child very happy about it) over activities that contribute to children's development in the long term (e.g. helping their children read every day so they become confident readers over time).

Furthermore, when making investment decisions, parents need to weigh the potential positive and negative outcomes of their choices, and in most cases these assessments are done with imperfect information about future potential outcomes. This opens the door for ‘optimism bias’ to distort parental assessments of potential outcomes in a way that downplays the possibility of negative events.

When parents make investment decisions, they also need to interpret behaviour and respond to preferences. This makes parental decisions potentially subject to ‘attribution bias’, which is a tendency to systematically make errors when they attempt to explain others’ behaviours. There are a number of attribution biases. Among the most relevant for parenting are ‘self-serving attribution bias’ and ‘hostile attribution bias’. Self-serving attribution bias is the tendency to attribute positive events to their character, but attribute negative results or events to external factors unrelated to themselves and their faults. For example, as explained by Mayer, Kalil and Klein (2020), a parent of a child who behaves well may attribute the child's behaviour to his or her own good parenting. But when the child misbehaves the parent may attribute that behaviour to the child being ‘bad’ or having bad influences.

Hostile attribution bias is the tendency to interpret others’ ambiguous behaviours or intentions as hostile or aggressive, even when there is no clear evidence of such intent. For example, a parent with hostile attribution bias may assume that their child having a tantrum in a supermarket is doing this to upset the parent (instead of, say, the child being tired) and may respond by shouting or even hitting the child. In turn, this harsh discipline may reinforce behaviour problems in their child.

Finally, as parents need to make a host of decisions without knowing a lot of parameters about them (e.g. their consequences for their children or themselves, and their psychological, monetary and time costs), there are a host of possible biases relating to where parents draw their information from and the weight they attribute to different sources of information. Among them, ‘attentional bias’ describes parents’ potential tendency to focus their attention more on certain types of information or stimuli over others, often due to their personal experiences, emotions or motivations. ‘Authority bias’ is the tendency to attribute greater accuracy, credibility or importance to the opinion or instructions of an authority figure, often without critically evaluating the content of their statements. The ‘bandwagon effect’ refers to the tendency of individuals to adopt a particular behaviour, belief or trend simply because others are doing so. And ‘confirmation bias’ is the tendency to seek out, interpret and remember information in a way that confirms one's pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses, while giving less consideration to information that contradicts them.

Finally, because of its complexity, parental decision-making may also be subject to ‘status quo bias’, which describes the tendency to prefer the current state of affairs and resist changes, even when change might lead to better outcomes, resulting from a combination fear of loss, aversion to uncertainty, and the perception that maintaining the current situation requires less effort or risk.

Before turning to the empirical evidence about the family investment and family stress pathways, we make two short remarks about this behavioural perspective on parenting. First, while the behavioural perspective on the impact of financial stress on cognitive functions is related to the family stress pathway in that it is the worry and stress resulting from poverty that ultimately hurt children's outcomes, the mechanism through which stress affects children's outcomes is different from the traditional family stress pathway. In this behavioural perspective, worry and stress are posited to affect decision-making by reducing cognitive resources needed to make decisions. Under the traditional family stress model, the strain of having fewer resources available for day-to-day living induces psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety, which affects children either via direct biological channels in utero or indirectly by affecting the quality of child–parent interactions.

Second, while this behavioural perspective rests on the premise that parents from low socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to be subject to these cognitive biases, this strand of the literature is not always clear as to whether it is the contemporaneous experience of poverty and financial stress that creates or exacerbates these biases or whether these biases arise for other factors correlated with poverty, such as the trauma that parents hold from having grown up in poverty or particular social networks. We return to discussing this point in the next section when reviewing the empirical evidence.

4 EVIDENCE ON THE MECHANISMS UNDERLYING THE (CAUSAL) LINK BETWEEN POVERTY AND CHILD OUTCOMES

Having reviewed different theoretical perspectives on the link between poverty, parental decisions and child outcomes, we now turn to the empirical evidence that exists to support these different mechanisms. There is ample correlational evidence of an association between family income and different types of investments or inputs that are believed to influence child development, such as expenditures on child-development-enhancing goods (for which we would expect a more mechanical link with family income), quantity and quality of parental time spent on different activities, warmth and conflict in parent–child interactions, inter-parental conflict, parental mental health, etc.

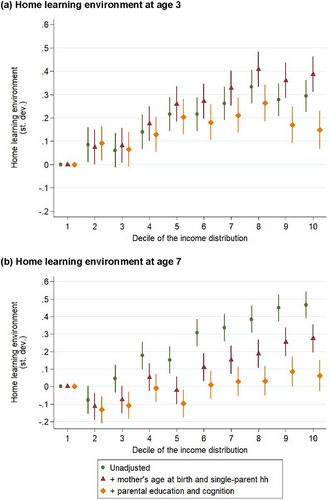

To illustrate this point for the UK, we describe in Figure 3 the unconditional family income gradient in the home learning environment at age 3 and age 7, respectively.2 The measure we focus on is an index summarising the frequency of various child stimulation activities, such as reading and playing.

Income gradients in the home learning environment at age 3 and age 7 in the MCS. Note: The estimates are derived from a regression of the home learning environment index on income decile dummies, based on equivalised household income at age 3 and 7, respectively. Two additional models are estimated: the first includes household controls such as the mother's age at birth and single-parent status, while the second adds controls for parental education and cognition, measured when the child is aged 14. The estimation sample is consistent across all regressions and weighted to be representative of the UK population.

Figure 3 describes income gradients in this measure of home learning environment at ages 3 and 7. Each dot represents the difference in the home learning environment of a child in each family income decile (from deciles 2 to 10) relative to children in the first family income decile (which is why the dot for the first decile takes the value zero). We begin by showing unadjusted income gradients, then we control first for maternal age at birth and whether the child is in a single-parent family, and then we include additional controls for parental education and cognitive ability (we describe our measure for parental education and cognition in the online Appendix).

The unadjusted gradients suggest that, at both ages 3 and 7, children in the wealthiest families (decile 10 of the family income distribution) have home learning environments approximately 0.3 and 0.45 SD higher, respectively, than those in the poorest families (decile 1). This difference, however, decreases substantially once we include controls for maternal education and cognitive ability. Our analysis therefore suggests that family income is highly correlated with all of these factors (some of which are measured after the home learning environment).

These values are reminiscent of those in Carneiro and Heckman (2002), which suggest that family income on its own, especially if measured at age 17, is unlikely to explain why individuals of poor families attend university at lower rates than those of wealthier families. These differences are more likely to be due to long-term family factors, crystallised in an individual's cognitive ability at age 17. What is perhaps surprising here (and in the work of Cattan et al., 2024) is that even income at ages 3 and 7 does not, on its own, appear to be a very strong predictor of child outcomes. After controlling for parental and family characteristics that arguably predate family income at these ages, income gradients in child outcomes and parental investments become relatively small. While these results do not mean that providing households with income transfers will not affect parental investments, they suggest that policies and interventions that reduce family income gaps alone (even if they occur in childhood, and especially if they are transitory income transfers, uncorrelated with the long-term family factors we control for) will only close a fraction of gaps in parental investments.

Of course, while these correlations could reflect the causal link between family income and parental investments hypothesised by the three theories reviewed in the previous section, they could also be driven by an omitted variable bias and reflect a correlation between the influence of other characteristics of parents and of their broader environments that are correlated with income. For this reason, we focus the rest of our discussion on experimental and quasi-experimental studies that aim to identify a causal effect of family income on different dimensions of parental investments.

Table 1 summarises studies that provide (causal) evidence of the impact of an exogenous shift in family income on monetary investments (to support the family investment model) and family stress and its consequences on parent–child interactions (to support the family stress model). Relative to the family investment and family stress model, we note there is, to date, much less evidence about the link between family income and cognitive biases that affect parental decision-making to support the third, behavioural perspective on family stress. We describe the type of evidence available to date at the end of this section.

| Paper | Context | Relevant population | Method | Child outcomes | Parental outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akee et al. (2010) | US. A casino opened on the Eastern Cherokee reservation in North Carolina, and a share of the profits was distributed to adult tribal members. | Low-income Native American | Differences-in differences |

Educational attainment and criminal behaviour Among the poorest children in the sample, an average annual increase of $4,000 in household income led to an additional year of education by age 21 and a 22 per cent reduction in the likelihood of committing a minor crime at ages 16 and 17. |

Parental behavioural and quality measures Reduced criminal behaviour among mothers and fathers of eligible households. Improvements in mothers’ and fathers’ supervision of their children and in parent–child interactions. |

| Bastian and Lochner (2022) | US. Federal and state EITC expansions (2003–18). | Low-income families | Maximum benefits approach |

Time investments An increase of $1,000 in the maximum possible EITC benefits for unmarried women is associated with a 3 percentage point (pp) rise in employment and a reduction of two hours in average weekly time spent with children. However, the EITC has negligible effects on time dedicated to active investment activities, such as helping with homework, playing sports or doing arts and crafts. The decrease in weekly investment hours is an insignificant 0.1 hours. |

|

| Baughman and Duchovny (2016) | US. Large expansion of the federal EITC in the late 1980s and early 1990s. | Sample of women with less than college education | Difference-in-differences (with a simulated benefit strategy) |

Child health A $100 increase in the median state EITC benefit leads to a 1.2 pp decrease in the likelihood of the mother reporting her child (aged 6–14) is in fair or poor health; and a 3.5 pp increase of being in excellent health. |

Health investments A $100 increase in the median state EITC benefit leads to a 4 pp increase in the likelihood of having private health insurance (for families with children aged 6–14). |

| Boyd-Swan et al. (2016) | US. EITC (OBRA90 expansions). | Sample of women with a high school degree or less | Differences-in-differences |

Maternal mental health The EITC resulted in a 15.7% reduction in depression scores among married mothers and a 4.4% increase in self-reported happiness. Moreover, married mothers were 8.5% more likely to report a sense of self-worth and 10.1% more likely to feel self-efficacy compared to their childless counterparts. |

|

| Evans and Garthwaite (2014) | US. EITC (OBRA93 expansions). | Sample of women with a high school degree or less | Differences-in-differences |

Maternal health The EITC reduced the number of reported poor mental health days and the total number of risky biomarkers among mothers with high school education or less and two or more children, compared with similar women with just one child. Specifically, a $500 increase in EITC payments would lead to a 19 per cent reduction in the number of poor mental health days in the past 30 days. Suggestive evidence indicates that the increased payments raised the likelihood of reporting excellent or very good health by approximately 1.35 pp, from a baseline of 57.7 per cent. |

|

| Gennetian and Miller (2002) | US. Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP): a state's welfare reform programme for low-income families with children. | Low-income families | Randomised controlled trial (RCT) |

Cognitive and socio-emotional development Households were randomly assigned either to the MFIP program (treatment) or to the traditional Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) programme (control). The MFIP had a positive impact on school performance (effect size of 0.16 SD) and reduced maternal reports of children's problem behaviour (effect size of −0.16 SD). |

Maternal mental health and home environment The MFIP led to significant reductions in maternal depression, including an 8.4 pp reduction in the risk of clinical depression (a 27 per cent relative decrease compared with the control group). No significant effects on the home environment or any parenting measures. |

| Gennetian et al. (2024) | US. Baby's First Years: unconditional cash transfer RCT controlled trial in the US starting at the time of a child's birth. | Low-income mothers | RCT |

Parental investments The treatment group (high-cash-gift mothers) received $333 monthly for three years and the control group (low-cash-gift mothers) received $20 monthly for the same duration. High-cash-gift mothers were more likely to report reading books or telling stories than low-cash-gift mothers (∼11.3 minutes more per week, a 5.2 per cent increase). High-cash-gift mothers spent $67.8 more per month than low-cash-gift mothers on an index that aggregates expenditures on focal child-specific goods, such as books, toys, clothes, electronics, activities and diapers (this estimate combines data from three waves around one, two and three years after birth). There is no evidence that high-cash-gift mothers report higher levels of subjective well-being. |

|

| Hamad and Rehkopf (2016) | US. EITC. | Low-income families | Multivariate linear regressions and instrumental variables |

Socio-emotional development Larger EITC payments improved the scores of the Behavioural Problems Index (BPI) at a two-year follow-up: for every $1,000 increase in income due to EITC payments, there is a decrease of about 0.03 SD in the BPI score. The effects vanish at the four-year follow-up. |

Home learning environment Instrumental variables models predict improved HOME scoresa at the four-year follow-up: for every $1,000 increase in income due to EITC payments, there is an increase of 0.04 SD in the HOME score. There is no association at the two-year follow-up. |

| Hart et al. (2024) | US. Baby's First Years: unconditional cash transfer RCT in the US starting at the time of a child's birth. | Low-income mothers | RCT |

Language and socio-emotional development Cash transfers did not have detectable impacts on maternal reports of child language or socio-emotional development in the first three years of life. |

|

| Macours, Schady and Vakis (2012) | Nicaragua. Atención a Crisis: random assignment to a cash transfer package at the community level (56 intervention and 50 control communities) targeting households with children aged 0–5. | Low-income households in rural areas | RCT |

Child health and development Children from recipient families had cognitive and socio-development scores 0.12 SD higher than the control group in 2006; and 0.08 SD higher in 2008, two years after the programme had ended. These outcomes were measured during early and mid-childhood, up to 83 months, at the time of the study's follow-up survey. The programme had a positive impact on health and motor outcomes of 0.05 SD in 2006 and 0.07 SD in 2008. |

Parental monetary investments The programme changed the composition of food expenditures (less weight on staple foods and more weight on animal proteins, fruits and vegetables) and had a substantial impact on health expenditures (mean increase of 0.13 SD among treated households). The programme led to increases in various measures of child stimulation, including telling stories, singing, reading to the child, and having pens, paper and toys available in the home. The mean increase in stimulation was 0.26 SD. |

| Milligan and Stabile (2011) | Canada. Province-level variation in the generosity of the National Child Benefit programme, a supplement for the Canada Child Tax Benefit. | All income groups | Simulated benefit strategy |

Educational outcomes and health A $1,000 increase in child benefits improved the maths scores of children under age 10 living with mothers who had a high school education or less by 6.9 per cent of an SD. The impact on boys’ maths scores was particularly substantial, showing an increase of 23.1 per cent of an SD. Child benefits also significantly enhanced children's mental health, particularly among girls, while improving the physical health of boys. |

Maternal mental health Child benefits improved maternal mental health: an additional $1,000 in child benefits reduced maternal depression scores by 10 per cent of an SD overall and by 20 per cent among mothers with lower levels of education. |

| Paxson and Schady (2010) | Ecuador. Roll-out of the Bono de Desarrollo Humano (a means-tested family benefit that provided $15 per month per family, equivalent to a 10 per cent increase in family expenditures for the average eligible household). | Low-income families | RCT |

Child health and development The average effect of the programme on eligible children's cognitive and behavioural scores and physical health (ages 3–7) was 5 per cent and 6 per cent of an SD, respectively. Treatment effects were larger for the poorest families, with children in the lowest expenditure quartile showing scores 18 per cent and 16 per cent of an SD higher than those in the control group, respectively. |

Health and time investments and maternal health The programme improved some dimensions of healthcare use and the HOME score,a particularly among treated children in the poorest quartile. While the poorest mothers in the treatment group experienced improvements in their haemoglobin levels, there were no significant impacts on maternal mental health. |

- Note: (a) The authors use the Home Observation Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Short Form (SF), a widely used tool from the NLSY79 child survey, designed to assess the quality and quantity of stimulation and support available to a child in the home environment. The HOME-SF evaluates several aspects of the home setting, including the physical environment, parental responsiveness to the child's needs, parental engagement in activities such as reading or playing, and the availability of learning materials.

4.1 Evidence to support the family investment model

In line with the family investment model, there are a few studies providing evidence that an exogenous increase in family income results in changes in parental expenditures on items that are believed to be child-development-enhancing. For example, Baughman and Duchovny (2016) exploit variation in state-level Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) to estimate the effects of the credit on health insurance coverage, utilisation of medical care and health status. They find that receipt of a more generous credit leads to significant changes in health insurance coverage patterns for children aged 6–14, increasing rates of private health insurance, but offsetting decreases in public coverage. They also find that these changes are associated with significant improvements in health status for older children, which is consistent with greater family income (used to purchase health-enhancing inputs) and/or more effective health insurance coverage.

Evidence supporting the family investment model also comes from the Baby's First Years study, a recent unconditional cash transfer to mothers starting at the time of birth in the US whereby the treatment group receives $333 monthly for three years and the control group receives $20 monthly for the same duration (the treatment amount is roughly equivalent to raising the annual income of a family of three living at the poverty line ($21,330 in 2019) by nearly 20 per cent). Gennetian et al. (2024) find that high-cash-gift mothers spent $67.80 more per month, on average, than low-cash-gift mothers on child-specific goods, such as books, toys, clothes, electronics, activities and diapers. This estimate combines data from three waves conducted approximately one, two and three years after the infant's birth.

Finally, in the context of a low-income country (i.e. Nicaragua), Macours, Schady and Vakis (2012) find that the receipt of an unconditional cash transfer led to significant improvements in the composition of food expenditures (less weight on staple foods and more weight on animal proteins, fruits and vegetables) and had a substantial impact on health expenditures (mean increase of 0.13 SD among treated households). Particularly, children in randomised households were more likely to have been weighed, to have received iron, vitamins or deworming medicine, and to have spent fewer days in bed.

While our review of the literature does not claim to be exhaustive, there is some evidence documenting how parental monetary investments shift when income increases. That said, we still know relatively little about families’ marginal propensity to invest in child-development-enhancing inputs when their income shifts and what may affect such propensity. Indeed, the existing evidence raises an interesting question about whether, even in the case of unconditional cash transfers, the way the cash is disbursed contributes to parents’ investment response. For example, and as discussed in Macours, Schady and Vakis (2012), even though the Nicaragua cash transfer was unconditional, it was labelled in a way to suggest a child development focus, potentially priming parents to spend more of these extra resources on child-focused expenditures than they would have otherwise done. This may also be the case with the US Baby's First Years trial, whose name and anchoring around child's birth may prime parents to spend the extra money on child-related expenditures.

4.2 Evidence to support the family stress model

Table 1 also describes a number of studies that report experimental or quasi-experimental evidence that an increase in family income leads to improved parental mental health and parent–child interactions. Akee et al. (2010) exploit the opening of a casino on the Eastern Cherokee reservation in rural North Carolina and compare the outcomes of tribal families who were eligible for a regular casino disbursement of a portion of the profits to those of non-eligible (non-tribal) families. In addition to finding impacts on children's education and likelihood of committing a crime in adulthood, the authors explore the hypothesis that parental quality improved with additional income, due to lower levels of household stress and disruption. They find that fathers in eligible households have a reduced probability of being arrested, particularly in households that were previously in poverty. They also find that both mothers and fathers have increased levels of supervision over their children (i.e. they know more about their children's whereabouts and activities), and mothers have more positive interactions with their children (they also find a positive effect for fathers, but it is not statistically significantly). They interpret these results as an indication that parents are engaging in less destructive behaviour, which is likely to spill over into parent–child interactions and supervision.

In another study of the impact of the EITC on children and parental outcomes, Evans and Garthwaite (2014) report quasi-experimental evidence of an impact of the increased tax credit on parental mental health. Specifically, they find that the 1993 expansion of the EITC for households with at least two children reduced the number of reported poor mental health days and the total number of risky biomarkers among mothers with high school education or less, compared with similar women who have just one child. Boyd-Swan et al. (2016) examine the 1990 EITC expansion (OBRA90) and report that, among married mothers, the reform led to a 15.7 per cent reduction in depression scores, a 4.4 per cent increase in self-reported happiness and an increase in the likelihood of feeling of self-worth (8.5 per cent) and self-efficacy (10.1 per cent) relative to their childless counterparts. Together, these studies underscore the significant role of the EITC in improving maternal mental health outcomes. While neither of these studies reports impacts on children's outcomes, in another study of the EITC, Hamad and Rehkopf (2016) find impacts of the increased credit on children's behaviours and improved scores on the Home Observation Measurement of the Environment (HOME), an extensively used tool to measure the quality of a child's home environment.

In another quasi-experimental study, Milligan and Stabile (2011) exploit province-level variation in the generosity of the National Child Benefit programme – see Michelmore (2025) for a discussion of the programme – and document a strong positive effect on the test scores of boys living with mothers with high school education or less, and significant improvements in the physical health of boys, as well as the mental health of girls. The authors also find evidence of improved maternal mental health in these families, which they postulate to be one mechanism driving the impacts on children's outcomes, in line with the family stress model.

Finally, Gennetian and Miller (2002) evaluate the impacts of the Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP). The MFIP programme differed from the traditional Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) programme primarily by reducing the penalty for work through greater financial incentives and requiring two-parent families to participate in employment and training after six months of assistance. Gennetian and Miller (2002) compare outcomes for children of mothers in three groups: a control group (AFDC), those who received financial incentives to work, and those who received both incentives and mandatory employment services. The MFIP had a positive impact on school performance (with an effect size of 0.16 SD) and reduced maternal reports of children's problem behaviour (an effect size of −0.16 SD). Furthermore, the MFIP's incentive-based treatment led to significant reductions in maternal depression, including an 8.4 pp reduction in the risk of clinical depression (a 27 per cent relative decrease compared to the control group). The authors do not report significant effects on the home environment or any parenting measures.

Overall, there does exist some robust evidence supporting the idea that increased family income leads to improved parental mental health and that this may be a mechanism driving improved children's outcomes The number of studies we have found is not very large, and the lack of more research on this relationship could be driven by the fact that data on parental mental health and family functioning are not widely available and/or by the fact that studies may be rarely powered to detect such impacts. Importantly, there are also studies that report no effect of an increase in parental income on improved parental mental health. For example, evaluations of the Baby First's Years cash transfer trial (Magnuson et al., 2022) and of the roll-out of the Bono de Desarrollo Humano (means-tested family benefit) find no evidence of an impact on maternal subjective well-being and maternal mental health, respectively. It is still unclear what makes these cash transfers different from other studies that find impacts on parental mental health. Perhaps the change in family income is too small or not permanent enough to meaningfully relieve parental stress induced by not having enough resources to cover day-to-day expenses. And in contexts where the income shift is small to moderate and known to be temporary, parents may also feel more stressed about how to make the most of this opportunity. Understanding better this heterogeneity across studies seems an important avenue for future research.

4.3 Evidence on the impact of poverty on parental cognitive functions

Finally, we review the empirical evidence to support the idea that poverty has a negative effect on children through its impact on parental cognitive functions and parenting decisions. Unlike the studies that we have reviewed so far and that provide more direct evidence of the impact of a conditional or unconditional cash transfer on parental behaviour and child outcomes, the behavioural strand of this literature has so far generated more indirect evidence about the link between poverty, parenting and children's outcomes.

We distinguish between two subgroups of studies. On the one hand, a few studies conduct lab-in-the-field experiments whereby they exogenously vary financial worries among relatively disadvantaged families and study how parental investments change as a result. On the other hand, another group of studies is interested in designing and evaluating, via RCTs, behaviourally informed interventions to shift parenting behaviours by relieving specific cognitive biases. In contrast with the first strand, these studies do not aim to demonstrate directly that poverty or financial worries affect parental decision-making. In fact, these studies are less interested in establishing whether poverty itself or a correlate of poverty is the active ingredient driving the cognitive bias in the parent, as much as they are interested in understanding how they can nudge parents in shifting their behaviours.

To our knowledge, Burlacu et al. (2023) and Lichand et al. (2022) are the most rigorous and relevant examples of the first type of studies aiming to prove a link between financial worry and parental behaviour. Burlacu et al. (2023) run a cross-cutting design that sequentially combines a psychological intervention triggering financial worries with an economic intervention offering financial subsidies to test parents’ present bias. For the first intervention, they use a technique called ‘priming’, whereby they ask richer and poorer parents how they would cope with hypothetical financial demands associated with everyday scenarios in British life. The idea is that more financially challenging scenarios will trigger greater financial worry in the poor than in the rich, thus depleting the mental bandwidth of this group more than among the better-off group. For the second intervention, they ask parents to allocate a budget of £30 in an experimental market across product categories reflecting immediate versus long-term priorities, and expose a randomised group of parents to a 50 per cent discount on items that fulfil a longer-term priority (i.e. child development products). The authors find that both low-income and higher-income parents increase their demand for the subsidised products, but when primed with financial worries under the same budget, low-income parents respond less to the subsidy, prioritising instead the purchase of products addressing immediate household needs. They further report evidence that this lower responsiveness to subsidies appears to be driven by worried parents who are further away from their previous payday.

Lichand et al. (2022) also studies how financial worries reallocate poor parents’ attention to immediate needs among a sample of primary caregivers of public high-school students in Brazil. They set up an experimental setting whereby they endow caregivers with experimental currency that they can either invest in an educational programme or keep as airtime credit on their phones. The educational programme sends weekly text messages to motivate parents to participate in their children's school life via reminders and encouragement messages. Through their participation in a previous experiment involving the educational programme, all participants in this experiment already know of it and some of them know of its substantial returns. In the study, Lichand et al. (2022) use the same priming technique as Burlacu et al. (2023) to increase financial worry among a randomly assigned group of caregivers, and ask all participants whether they would invest their experimental currency. The authors find that those primed about financial worries invest less in the educational programme, despite the fact that they have the financial means to undertake the investment and that they have the chance to learn about its returns and the ability to commit to their decision. They interpret this evidence as demonstrating that the effect of poverty requires immediate attention, which likely discourages poor parents from undertaking investments whose costs are in the present and whose benefits are only in the future.

A second strand of behaviourally informed studies focuses on designing and evaluating interventions that nudge parents’ behaviour to address the specific cognitive biases we discussed above. These very interesting studies often aim to address a number of biases within the same intervention. While this may make the intervention more effective, it also means that it is not always possible to infer from the evaluation the relative salience of different biases on parental behaviours and how they might interact with each other (Mayer, Kalil and Klein, 2020). In the remainder of this section, we review some of the most prominent interventions that demonstrate how behavioural tools can help manage cognitive biases.

The first intervention, Parent and Children Together (PACT), is an experiment designed to increase the frequency of book reading among low-income families by helping parents overcome present bias through a set of behavioural tools (goal setting, feedback, reminders and social rewards) to ‘bring the future to the present’ and help parents form a habit of regular book reading. Mayer et al. (2019) find that the intervention increased the number of minutes that parents read to their children (using an electronic application) by 1 SD (i.e. twice as much reading time compared to the control group mean). This increase was greater for parents with a high discount rate for the future, suggesting that indeed the intervention worked at least in part by addressing parents’ present bias.

The second example of a behaviourally informed intervention is called Show Up 2 Grow Up (SUGU) and is designed to reduce chronic absenteeism in preschool. The intervention again implements a series of text messages (four to six per week) that target ‘cognitive roadblocks’ that are driving absences, such as present bias (by making the benefits of attendance more present), and correcting inaccuracies in parental knowledge of the importance of attendance. Specifically, the messages emphasise the importance of preschool learning concepts for kindergarten readiness, prompt parents to identify obstacles to attendance and create plans to address these obstacles, provide information to parents about their children's monthly, attendance rates and remind parents to maintain a goal of daily attendance. Testing the impact of the intervention in an RCT, Kalil, Mayer and Gallegos (2021) find that the intervention increased attended days by 2.5 (0.15 SD) and decreased chronic absenteeism by 9.3 pp (20 per cent) over an 18-week period, with these impacts being stronger among those with the poorest attendance at baseline and those who had the weakest beliefs about the importance of attendance to their children's development.

The third intervention, Parent Corps, is also a family-centred, school-based intervention to promote school readiness and healthy development in preschoolers. The programme includes professional development for prekindergarten and kindergarten teachers and weekly sessions for parents in which a mental health professional teaches strategies for promoting social, emotional and behavioural regulation skills. The programme was trialled in New York City kindergartens and was found to lead to better mental health and academic performance three years later (Brotman et al., 2016). More recently, researchers from the beELL initiative redesigned a few aspects of the model delivery in order to increase parental engagement with the programme by addressing the potentially negative effects of a number of biases. For example, parent materials were redesigned to de-emphasise the aim of improving parental skills and instead frame the programme's purpose as helping students succeed, in order to counter possible hostile attribution bias. The materials include a parent-directed ‘myth-busters’ flyer to respond to possible optimism bias and to counter beliefs such as ‘I don't need a parenting programme, I've already raised children’. Finally, the programme sent out short videos with parent testimonials to encourage parents to attend workshops held by ParentCorps and to circumvent the bandwagon effect.

The Thirty Million Words (TMW) Lab led by Dana Suskind at the University of Chicago has also created a host of interventions leveraging a cohesive set of behavioural nudges to shape overall parenting behaviours. As discussed in List, Samek and Suskind (2018), by teaching the key concepts of the TMW curriculum with the same central behavioural tools (e.g. the TMW 3Ts – Tune In, Talk more, Take turns), TMW reduces the cognitive load of the intervention on participants. To reduce present bias, each module in the curriculum emphasises the importance of what parents can do/need to do now and how their interactions will positively affect their child's future development. To support parental plan-making and provide immediate evidence of impact, the interventions provide quantitative linguistic feedback via a digital recorder that tracks parent input and parent–child interactions. Finally, the interventions remind parents of the desired change in behaviours using personalised text messages. Importantly, these messages are framed in a way that prime their identities as parents to motivate them to use the power of their words to improve their child's development. The TMW interventions have been evaluated in a number of RCTs, which find that the new parenting behaviours were sustained over time, leading to improved outcomes for children in early childhood (Leung, Hernandez and Suskind, 2020; Leung, Trinidad and Suskind, 2023; Leung and Suskind, 2024).

The final example of a behaviourally informed parenting intervention is a collaboration between the beELL Lab and the New York City (NYC) Newborn Home Visiting Program around the design of the Talk to Your Baby (TTYB) programme, an early language and literacy intervention that uses text messages to support positive parenting and prompt parents to read, sing and talk to their babies. The beELL–NYC collaboration tested the impact of automatically enrolling new mothers in the programme (with the option of opting out at any time) in order to combat status quo bias. The results were astonishing, with 95 per cent of parents automatically enrolled participating in the programme versus only 1 per cent among parents who had to opt in on their own (Gennetian et al., 2020).

5 DISCUSSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Policymakers interested in breaking the link between family income and children's outcomes usually consider two broad types of policy levers: policies to improve parental capabilities and policies to reduce poverty (Eisenstadt and Oppenheim, 2019). The former include in-kind services, such as programmes to support parental mental health, to provide information about safe and stimulating parenting and/or to reduce inter-parental conflict. The latter include policies to improve family income, such as (conditional or unconditional) cash transfers, subsidies to reduce the cost of goods or services (e.g. childcare, food, housing subsidies, healthcare) and/or policies to incentivise work (e.g. tax credits, minimum wage increases). Depending on their nature, these policies will affect factors or inputs that can affect child development (e.g. the time that children spend in formal childcare and with their parents) over and beyond their impact on families’ financial resources.

To design policy in this area, governments face incredibly difficult questions about how to design, dose and target the combination of policy instruments that will have the greatest impact on children's outcomes, ideally at the smallest cost to the exchequer. While many of these policies may promote multiple outcomes that governments care about (e.g. an employment policy could both reduce poverty and promote economic growth), that is often not the case, creating trade-offs between competing priorities for public funds.

In many countries, policymakers increasingly seek to inform their choices in the evidence and demonstrate the ‘value-for-money’ of policy options before they are funded. These calculations are important, but it would be naïve to think that robust research is always available to answer such complex and multiple questions for the particular context of interest. Instead, policymakers will often have to piece together what the evidence (often from other contexts than their own) suggests about the possible impact of their choices, and to act with a high degree of uncertainty. Hence, the importance of frequently synthesising bodies of related literature, and clarifying what the evidence suggests and where the gaps remain, so that future research efforts can be directed towards those gaps.

This paper – and the other two papers in this symposium – review and discuss what we know of the impact of policies to boost family income on children's outcomes. This discussion is timely in the context of the UK, where a recently elected Labour government has committed to reduce child poverty and set as one of its five missions to break the barriers to opportunities for children. The first paper in the symposium (Aizer and Lleras-Muney, 2025) focuses on the impact of unconditional cash transfers on children's health, well-being and adult outcomes. The second (Michelmore, 2025) focuses on cash and in-kind benefits to incentivise employment and work. These follow recent syntheses of the literature looking at the impact of family income on child poverty (Duncan and Le Menestrel, 2019) and on children's outcomes (Cooper and Stewart, 2021; Page, 2024) and covering a broad array of policy instruments.

All these studies, including ours, agree that there is now robust evidence that raising families’ disposable income can lead to improvements in children's outcomes. While this may sound obvious, up until fairly recently we did not have robust evidence on this basic question. This progress on causal inference has been achieved thanks to the use of more experimental designs, as well as quasi-experimental designs exploiting a variety of policy reforms in different (mostly developed) contexts.